1.1 Introduction to Culture and Psychology

Read 1.1 Introduction to Culture and Psychology

What comes to mind when we think of the word culture? Some of us might think of people of a different race, ethnicity, or religion with different customs and traditions; others might think of music, the arts, or different foods when we think of culture. All of these would be correct. Culture is generally defined as an interrelated set of values, tools, and practices shared among a group of people with a common social identity. It shares characteristics and knowledge, including language, religion, customs, social behaviors, music, arts, and cuisine.

Culture encompasses human elements beyond biology: for example, our norms and values, the stories we tell, learned or acquired behaviors, religious beliefs, art and fashion, and so on. Culture is what differentiates one group or society from the next.

Different societies have different cultures; however, it is essential not to confuse the idea of culture with society. A culture represents the beliefs and practices of a group, while society represents the people who share those beliefs and practices. Neither society nor culture could exist without the other.

Almost every human behavior—shopping, marriage, and expression of feelings—is learned. Behavior based on learned customs is not necessarily bad—familiarity with unwritten rules helps people feel secure and confident that their behaviors will not be challenged or disrupted. However, even the most straightforward actions—such as commuting to work, ordering food from a restaurant, and greeting someone on the street—evidence a great deal of cultural propriety (which means conforming to conventionally accepted standards of behavior or morals).

This course will cover the psychological aspects of culture, including language, shared patterns of behavior and interaction, cognitive constructs, perceptions, knowledge, and understanding learned through socialization.

To further develop an understanding of cultural psychology, we will begin the course with a brief overview of the study of psychology.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the key goals of the field of psychology and cultural psychology.

- Identify the limitations of the traditional approach to conduct research.

- Consider the different ways that culture is learned.

- Compare and contrast individualist vs collectivist cultures.

“We seldom realize, for example, that our most private thoughts and emotions are not actually our own. For we think in terms of languages and images which we did not invent, but which were given to us by our society.” Alan Watts

Psychology and Culture

When you think about different cultures, you probably picture their most visible features, such as differences in how people dress or in the architectural styles of their buildings. You might consider different types of food or how people in some cultures eat with chopsticks while people in others use forks. There are differences in body language, religious practices, and wedding rituals. While these are all obvious examples of cultural differences, many distinctions are more challenging to see because they are psychological in nature. Culture goes beyond the way people dress and the food they eat. It also stipulates morality, identity, and social roles.

Before we delve further into the concept of culture, for this course, it is essential to have a basic understanding of the field of psychology. Psychology is often defined as the scientific study of the human mind and its functions, especially those affecting the behavior of the individual or group. Broadly speaking, psychology is the science of mind and behavior, including conscious and unconscious phenomena. Psychologists, practitioners, and researchers in the field explore the role that cognitive processes (thinking) have on individual and social behavior. Psychologists also examine the physiological and biological processes, including the brain, central nervous system, and neurotransmitters, which underlie individuals’ thinking and behavior patterns.

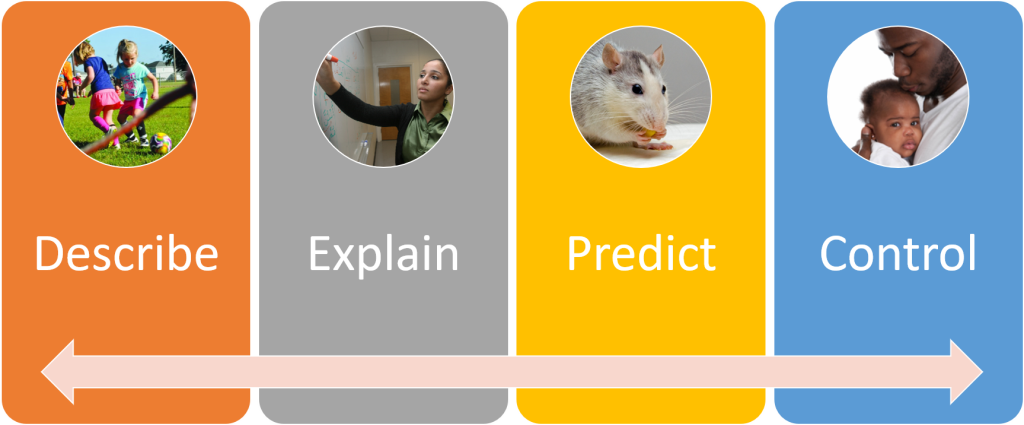

The Four Main Goals of Psychology

| Describe | Explain |

| The study of psychology describes the behavior of humans and other animals to improve our understanding of that behavior and to gain a sense of what can be considered normal or abnormal behavior. Psychological researchers use various research methods to help describe behavior, including experimentation, naturalistic observation, case studies, correlational studies, surveys, and psychological testing. The goal of describing behavior is to explain the behavior better. | To explain behavior, researchers must determine the causes of behavior. Psychological researchers attempt to understand individuals’ actions or reactions and then try to identify the factors that may have produced the behavior (for example, what occurred either before or after a particular behavior). Using the different types of research methods, researchers form theories and then test those theories to explain why people behave the way they do in specific situations. |

|---|

| Predict | Control |

|---|---|

| Once we know what happens and why it happens, we can begin to anticipate what will happen in the future. This is the third goal of psychology: to predict how an individual will behave or when the behavior will happen next. Predicting behavior is difficult; therefore, describing and explaining behavior gives way to predicting future behavior. Researchers may be better able to predict behavior by looking for patterns or examples of a particular behavior. Predicting behavior is essential for helping an individual to promote and encourage more positive, pro-social behavior and to modify harmful or dysfunctional behavior. | Finally, and perhaps most importantly, psychology strives to change, influence, or control behavior to make positive and lasting changes in people’s lives. It is important to note that it would be considered unethical for a psychologist to attempt to influence, shape, alter, or control someone’s behavior without asking for permission or getting consent. As noted earlier, the ultimate goal of psychology is to benefit individuals and society, but this is done by respecting the individual’s rights. |

Psychology as a Hub Science

Psychology is the scientific study of the mind and behavior. It is a multifaceted discipline with many subfields, such as human development, sports, health, clinical research, social behavior, and cognitive processes. While psychology has ancient philosophical roots, it emerged as a formal science over the past 150 years, with foundational contributions from figures like Wilhelm Wundt, Sigmund Freud, and B.F. Skinner (McLeod, 2019). It is considered a science because it investigates the causes of behavior using systematic and objective methods of observation, measurement, and analysis. This process is supported by empirical evidence, theoretical interpretations, generalizations, explanations, and predictions based on the scientific method (McLeod, 2019).

Psychology is also described as a “hub science,” meaning its research findings influence and are cited across many scientific fields. There are seven recognized hub sciences: mathematics, physics, chemistry, earth sciences, medicine, psychology, and the social sciences (Cacioppo, 2007). Psychology holds this status because its discoveries contribute to disciplines such as neuroscience, psychiatry, education, and even business management. For example, research in psychology has informed treatments for mental health disorders, improved educational practices, and shaped marketing strategies. By exploring the human mind and behavior, psychology addresses and helps solve problems across diverse areas of human activity, making it central to scientific understanding and societal progress.

Cultural WEIRDos

Although psychology is based on empirical evidence and research findings that are meant to be representative across a large segment of the general population, a growing number of researchers have come to realize that many vital considerations of human behavior have been overlooked in the study of psychology due to the over-sampling (test subjects) of W.E.I.R.D. populations. Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan coined the acronym W.E.I.R.D., which stands for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. 99% of all published studies rely on participants recruited from populations that fit those criteria. Therefore, findings from psychological research utilizing primarily W.E.I.R.D. populations are often labeled as universal theories that explain psychological phenomena but are inaccurately and inappropriately applied to other cultures.

In 2008, a researcher named Arnett pointed out a big problem: most psychology studies were based on people from the U.S., even though they make up only a small part of the world’s population. This raised a big question—can we trust psychology findings to apply to everyone if they mostly come from one country? Arnett and colleagues (Thalmayer et al. 2021) redid their study and found that between 2014 and 2018, 60% of the studies still used American participants. The rest mostly came from other English-speaking or Western European countries. So now, only about 11% of the world’s population is represented in top psychology research. People from the majority of the world are still mostly left out. Psychology still has a long way to go to truly understand all humans.

Recent research findings reveal that cultures differ in many areas, such as logical reasoning and social values, which have become increasingly difficult to ignore. For example, many studies have shown that Americans, Canadians, and Western Europeans rely on analytical reasoning strategies, which separate objects from their contexts to explain and predict behavior. Social psychologists refer to the fundamental attribution error or the tendency to explain people’s behavior in terms of internal, inherent personality traits rather than external, situational considerations (e.g., attributing an instance of angry behavior to an angry personality). Outside W.E.I.R.D. cultures, however, this phenomenon is less prominent, as many non-W.E.I.R.D. populations tend to pay more attention to the context in which behavior occurs. Asians tend to reason holistically, for example, by considering people’s behavior in terms of their situation; someone’s anger might be viewed as simply a result of an irritating day (Jones, 2010; Nisbet et al., 2005). Yet many long-standing theories of how humans think rely on the prominence of analytical thought (Heinrich, 2010).

By studying only W.E.I.R.D. populations, psychologists fail to account for a substantial amount of diversity in the global population. Applying the findings from W.E.I.R.D. populations to other populations can lead to a miscalculation of psychological theories and may hinder psychologists’ abilities to isolate fundamental cultural characteristics.

A primary goal of cultural psychology is to have many and varied cultures contribute to fundamental psychological theories to correct these theories so that they become more relevant to the predictions, descriptions, and explanations of all human behaviors, including many cultures, not just Western ones (Shweder & Levine, 1984).

The article Are your findings ‘WEIRD’? [new tab] further explains and provides insight into the implications of the oversampling of W.E.I.R.D. populations.

Cultural Psychology

Cultural psychology is an interdisciplinary study of how culture reflects and shapes the mind and behavior of its members (Heine, 2011). The main position of cultural psychology is that the mind and culture are inseparable, meaning that people are shaped by their culture, which is shaped by its people (Fiske et al., 1998). Shiraev and Levy (2013) describe cultural psychology as the idea that behavior and mental processes are essentially the products of an interaction between culture and the individual. Incorporating a cultural perspective in psychological research helps to ensure that the knowledge we learn is more accurate and descriptive of all people.

Cultural psychologists explore the general relationship between thought processes, behaviors, and culture. These psychologists investigate how cultural influences affect the mind and how the mind helps create cultural influences. According to cultural psychologists, it is a cyclic process in which the mind contributes to cultural behaviors, traditions, and beliefs, and in turn, those influences affect the mind. Cultural psychology studies identity, child development, emotions, social behavior/interactions, friendships/romantic relationships, and family dynamics.

The culture you live in is one of the most critical environmental factors shaping your personality (Triandis & Suh, 2002). Culture refers to a particular society’s beliefs, customs, art, and traditions. Culture is transmitted to people through language as well as through the modeling of culturally acceptable and unacceptable behaviors that are either rewarded or punished (Triandis & Suh, 2002). With these ideas in mind, personality psychologists have become interested in the role of culture in understanding personality. They ask whether personality traits are the same across cultures or if there are variations. It appears that both universal and culture-specific aspects account for variations in people’s personalities.

Culture is Learned

It’s important to understand that culture is learned. So then, how are different cultural behaviors learned? It turns out that cultural skills and knowledge are learned in much the same way a person might learn to do algebra or knit. They are acquired through a combination of explicit teaching and implicit learning, by observing and copying.

Cultural teaching can take many forms. It begins with parents and caregivers because they are the primary influence on young children.

Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works. They encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to say “Thank you.” They teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture. They introduce children to religious beliefs and the rituals that go with them. They even teach children how to think and feel! Adult men, for example, often exhibit a particular set of emotional expressions—such as being tough and not crying—that provide a model of masculinity for their children. This is why we see different ways of expressing the same emotions in other parts of the world.

In some societies, it is considered appropriate to conceal anger. Instead of expressing their feelings outright, people purse their lips, furrow their brows, and say little. In other cultures, however, it is appropriate to express anger. In these places, people are likelier to bare their teeth, furrow their brows, point or gesture, and yell (Matsumoto et al., 2010). Such patterns of behavior are learned. Often, adults are not even aware that they are, in essence, teaching psychology, because the lessons are happening through observational learning.

Let’s consider a single example of a way you behave that is learned, which might surprise you. All people gesture when they speak. We use our hands in fluid or choppy motions—to point things out or pantomime actions in stories. Consider how you might throw your hands up and exclaim, “I have no idea!” or how you might motion to a friend that it’s time to go. Even people who are born blind use hand gestures when they speak, so to some degree, this is a universal behavior, meaning all people naturally do it. However, social researchers have discovered that culture influences how a person gestures. Italians, for example, live in a society full of gestures. They use about 250 of them (Poggi, 2002)! Some are easy to understand, such as a hand against the belly, indicating hunger. Others, however, are more difficult. For example, pinching the thumb and index finger together and drawing a line backward at face level means “perfect,” while knocking a fist on the side of one’s head means “stubborn.”

Beyond observational learning, cultures also use rituals to teach people what is important. For example, young people interested in becoming Buddhist monks often have to endure rituals that help them shed feelings of specialness or superiority that run counter to Buddhist doctrine. To do this, they might be required to wash their teacher’s feet, scrub toilets, or perform other menial tasks. Similarly, many Jewish adolescents go through the process of bar and bat mitzvah. This is a ceremonial reading from scripture that requires the study of Hebrew and when completed, signals that the youth is ready for full participation in public worship.

Attending a Bar Mitzvah? Bat Mitzvah? (open YouTube video in new tab)

Cultural Intelligence

In a world that is increasingly connected by travel, technology, and business the ability to understand and appreciate the differences between cultures is more important than ever. Psychologists call this capability “cultural intelligence”. Cultural intelligence (CQ) refers to an individual’s ability to navigate and adapt to culturally diverse environments effectively. It involves understanding cultural norms, adjusting behaviors, and interacting successfully across cultural boundaries (Earley & Ang, 2003). CQ comprises four components: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral. Cognitive CQ encompasses knowledge of cultural norms and practices, such as understanding that maintaining direct eye contact is considered respectful in the U.S. but may be seen as confrontational in Japan. Metacognitive CQ involves reflecting on and adjusting cultural understanding in dynamic situations—for instance, realizing that a business negotiation in Brazil may require more informal conversation before getting to the point. Motivational CQ reflects an individual’s willingness to engage with different cultures, such as a teacher volunteering to work in an international school despite potential language barriers. Behavioral CQ refers to the capacity to modify verbal and non-verbal behaviors based on cultural expectations, such as using appropriate hand gestures when speaking to a multicultural audience (Van Dyne et al., 2012). Research indicates that individuals with high CQ are more effective in global leadership roles, conflict resolution, and intercultural collaborations, making CQ an essential skill in today’s globalized world (Ang et al., 2007).

How to Develop Cultural Intelligence

Gaining cultural intelligence is an intentional process involving both learning and experiential engagement. One can build cognitive CQ by studying cultural customs, history, and social norms through books, documentaries, and courses on intercultural communication. Developing metacognitive CQ involves practicing mindfulness and self-reflection to identify cultural biases and adjust perceptions. For example, keeping a cultural journal while traveling abroad can help track new cultural insights and personal growth. Motivational CQ can be enhanced by fostering a genuine interest in cultural diversity, perhaps by participating in cultural exchange programs or community service with diverse groups. Behavioral CQ is improved through direct interaction, such as working on international teams or engaging in culturally immersive experiences like study-abroad programs. These practices, when combined, create a well-rounded capacity to navigate cultural differences effectively (Thomas & Inkson, 2009).

Media Attributions

- john-schaidler-9V3Q2W_mRLE-unsplash © John Schaidler is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- parent reading is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- pexels-didsss-1366997 © Diana is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license