1.2 Defining Culture

Humans are social creatures. Since the dawn of homo sapiens nearly 250,000 years ago, people have grouped into communities to survive. Living together, people form everyday habits and behaviors—from specific methods of childrearing to preferred techniques for obtaining food. In modern-day Paris, many people shop daily at outdoor markets to pick up what they need for their evening meal, buying cheese, meat, and vegetables from different specialty stalls. In the United States, most people shop once a week at supermarkets, filling large carts to the brim. How would a Parisian perceive U.S. shopping behaviors that Americans take for granted?

As mentioned before, so much of what we do daily is learned. In the United States, people tend to view marriage as a choice between two people based on mutual feelings of love. In other nations and other times, marriages have been arranged through an intricate process of interviews and negotiations between entire families, or in other cases, through a direct system, such as a “mail order bride.” To someone raised in New York City, the marriage customs of a family from Nigeria may seem strange or even wrong. Conversely, someone from a traditional Indian family in Kolkata might be perplexed by the idea of romantic love as the foundation for marriage and lifelong commitment. In other words, how people view marriage depends mainly on what they have been taught and learned from their culture.

Culture is generally defined as an interrelated set of values, tools, and practices shared among a group of people with a common social identity. More simply, culture is the total of our worldviews or our ways of living. Cultural worldviews affect various psychological processes but are thought to influence social psychological processes and behavior most strongly. Because culture encompasses virtually everything that can be learned, it is ever-shifting, and not everyone follows the group’s beliefs. Subcultures are smaller groups within the larger culture that have varying—or additional—traditions and ideas. They tend to share much in common with the larger culture and typically interact with members of the majority regularly. Most people belong to at least one group classified as a subculture. Large groups of friends or family members tend to form their own subcultures. Subcultures often have their own language or traditions that are not followed by the larger group. One example of a subculture includes people who follow certain trends, such as gamers. Subcultures are often considered their own culture within the larger society.

Behaviors, values, beliefs, and norms are acquired through a process known as enculturation. This is the process by which people learn the dynamics of their surrounding culture and acquire values and norms appropriate or necessary in that culture. Enculturation begins with parents and caregivers because they are the primary influence on young children. Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works. They may encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to “say please and thank you.” They may teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture. Other influences on culture can be other adults and peers.

In everyday conversation, people rarely distinguish between the terms culture and society, but the terms have slightly different meanings, and the distinction is essential to a researcher. A society describes a group of people who share a community and a culture. By “community,” researchers refer to a definable region—as small as a neighborhood (Brooklyn, or “the east side of town”), as large as a country (Ethiopia, the United States, or Nepal), or somewhere in between (in the United States, this might include someone who identifies with Southern or Midwestern society). To clarify, a culture represents the beliefs and practices of a group, while society represents the people who share those beliefs and practices. Neither society nor culture could exist without the other.

Behavior based on learned customs is not a bad thing. Being familiar with unwritten rules helps people feel secure and “normal.” Most people want to live their daily lives confident that their behaviors will not be challenged or disrupted.

How would a visitor from the suburban United States act and feel on this crowded Tokyo train?

Take the case of going to work on public transportation. Many behaviors will be the same whether people are commuting in Dublin, Cairo, Mumbai, or San Francisco, but significant differences also arise between cultures. Typically, a passenger will find a marked bus stop or station, wait for the bus or train, pay an agent before or after boarding, and quietly take a seat if one is available. However, passengers might have to run when boarding a bus in Cairo because buses often do not come to a complete stop to take on passengers. Dublin bus riders would be expected to extend an arm to indicate that they want the bus to stop for them. And when boarding a commuter train in Mumbai, passengers must squeeze into overstuffed cars amid a lot of pushing and shoving on the crowded platforms. That kind of behavior would be considered the height of rudeness in the United States, but in Mumbai, it reflects the daily challenges of getting around on a train system taxed to capacity.

In this example of commuting, culture consists of thoughts (expectations about personal space, for example) and tangible things (bus stops, trains, and seating capacity). Material culture refers to the objects or belongings of a group of people. Metro passes and bus tokens are part of material culture, as are automobiles, stores, and the physical structures where people worship. Nonmaterial culture, in contrast, consists of a society’s ideas, attitudes, and beliefs. Material and nonmaterial aspects of culture are linked, and physical objects often symbolize cultural ideas. A metro pass is a material object, but it represents a form of nonmaterial culture, namely capitalism and the acceptance of paying for transportation. Clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry are part of material culture, but clothing appropriateness for specific events reflects nonmaterial culture. A school building belongs to material culture, but the teaching methods and educational standards are part of education’s nonmaterial culture. These material and nonmaterial aspects of culture can vary subtly from region to region. As people travel farther afield, moving from different regions to entirely different parts of the world, certain material and nonmaterial aspects of culture become dramatically unfamiliar. What happens when we encounter different cultures? As we interact with cultures other than our own, we become more aware of the differences and commonalities between others’ worlds and our own.

Elements of Culture

Values and Beliefs

The first and perhaps most crucial elements of culture we will discuss are its values and beliefs. Values are a culture’s standard for discerning what is good and just in society. Values are deeply embedded and critical for transmitting and teaching a culture’s beliefs. Beliefs are the tenets or convictions that people hold to be true. Individuals in a society have specific beliefs, but they also share collective values. To illustrate the difference, Americans commonly believe in the American Dream—that anyone who works hard enough will be successful and wealthy. Underlying this belief is the American value that wealth is good and important.

Values are not static; they vary across time and between groups as people evaluate, debate, and change collective societal beliefs. Values also vary from culture to culture. For example, cultures differ in their values about what kinds of physical closeness are appropriate in public. It’s rare to see two male friends or coworkers holding hands in the United States, where that behavior often symbolizes romantic feelings. But in many nations, masculine physical intimacy is considered natural in public. This difference in cultural values came to light when people reacted to photos of former president George W. Bush holding hands with the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia in 2005. A simple gesture, such as hand-holding, carries significant symbolic differences across cultures.

Norms

Norms define how to behave following what a culture or society has defined as good, correct, and important, and most members of the culture adhere to them. Members of a culture may engage in rituals used to teach people what is important. For example, young people who are interested in becoming Buddhist monks often have to endure rituals that help them shed feelings of specialness or superiority—feelings that run counter to Buddhist doctrine. To do this, they might be required to wash their teacher’s feet, scrub toilets, or perform other menial tasks. Similarly, many Jewish adolescents go through the process of bar and bat mitzvah. This is a ceremonial reading from scripture that requires the study of Hebrew and when completed, signals that the youth is ready for full participation in public worship.

Formal norms are established written rules. They are behaviors worked out and agreed upon to suit and serve the most people. Laws are formal norms, but so are employee manuals, college entrance exam requirements, and “no running” signs at swimming pools. Formal norms are the most specific and clearly stated of the various types of norms, and they are the most strictly enforced. However, even formal norms are enforced to varying degrees and are reflected in cultural values.

There are plenty of formal norms, but the list of informal norms—casual behaviors that are generally and widely conformed to—is longer. People learn informal norms by observation, imitation, and general socialization. Some informal norms are taught directly—“Kiss your Aunt Edna” or “Use your napkin”—while others are learned by observation, including observations of the consequences when someone else violates a norm. However, although informal norms define personal interactions, they extend into other systems as well. In the United States, there are informal norms regarding behavior at fast-food restaurants. Customers line up to order their food and leave when they are done. They don’t sit down at a table with strangers, sing loudly as they prepare their condiments, or nap in a booth. Most people don’t commit even benign breaches of informal norms. Informal norms dictate appropriate behaviors without the need for written rules.

Norms may be further classified as either mores or folkways. Mores (mor-ays) are norms that embody a group’s moral views and principles. Violating them can have serious consequences. The strongest mores are legally protected by laws or other formal norms. In the United States, for instance, stealing is considered immoral, and it’s punishable by law (a formal norm). But more often, mores are judged and guarded by public sentiment (an informal norm). People who violate mores are seen as shameful. They can even be shunned or banned from some groups. The mores of the U.S. school system, for example, require that a student’s writing be in the student’s own words or use special forms (such as quotation marks and a whole citation system) for crediting other writers. Writing another person’s words as if they are one’s own has a name—plagiarism. The consequences for violating this norm can range from lower course grades to expulsion.

Unlike mores, folkways are norms without any moral underpinnings. Instead, folkways direct appropriate behavior in a culture’s day-to-day practices and expressions. They indicate whether to shake hands or kiss on the cheek when greeting another person. They specify whether to wear a tie and blazer or a T-shirt and sandals to an event. In Canada, women can smile and say hello to men on the street. In Egypt, that’s not acceptable. In regions in the southern United States, bumping into an acquaintance means stopping to chat. It’s considered rude not to, no matter how busy one is. In other regions, people guard their privacy and value time efficiency. A simple nod of the head is enough. Other accepted folkways in the United States may include holding the door open for a stranger or giving someone a gift on their birthday. The rules regarding these folkways may change from culture to culture.

Many folkways are actions we take for granted. People must act without thinking to get seamlessly through daily routines; they can’t stop and analyze every action (Sumner, 1906). Those who experience culture shock may find that it subsides as they learn the new culture’s folkways and can move through their daily routines more smoothly. Folkways might be small manners learned by observation and imitated, but they are by no means trivial. Like mores and laws, these norms help people negotiate their daily lives within a given culture.

Four Features of Culture

Culture may hold a different meaning for different people. A standard definition is “what a group of people have in common with one another” (Baumeister & Bushman, 2014). For this course, we will examine four features of culture: 1) shared ideas, 2) culture as a system, 3) culture as praxis, and 4) culture as information and meaning. These four concepts of culture, as defined by Baumeister and Bushman (2014), describe how people interact with one another, instill a feeling of social acceptance, and provide a sense of belonging for the individual within the group.

- Shared Ideas

Culture is the world of shared ideas. Culture is the shared patterns of behaviors and interactions, cognitive constructs, and affective understanding learned through socialization. These shared ideas and patterns identify a cultural group’s members while distinguishing those of another group. Although artifacts, tools, or other tangible cultural elements can be representative a culture, the essence of a culture is how the members of the group interpret, use, and perceive them. People within a culture usually interpret the meaning of symbols, artifacts, and behaviors in the same or similar ways. Notions of modesty, conceptions of beauty, ideas governing child rearing, relationships to animals and nature, rates of social interactions, and so many other patterns of beliefs and behaviors are directed by culture. - Culture as a System

Culture exists as a network linking many different people. The idea of a network is helpful because it captures the essential point that culture connects many people together and exists in what they share. The problem with the idea of a network is that it does not sufficiently capture the dynamic (changing) aspect of culture. Culture never sits still and is ever-changing. Therefore, instead of a network, culture can be thought of more as a system consisting of many moving parts that work together. A cultural system is the interaction of different elements in culture. For example, how people used to get food: farmers grew it and sold it locally, and people bought it and shared their knowledge of preserving it and preparing it with others, usually their children. This system gave way to new ways of doing things. Nowadays, farmers still grow it, factories process it, truckers transport it, stores display it, and people buy it and cook it. Through the processes of transmission (shared knowledge) and adaptation (adapting to change), the action of obtaining food in the US and across the world has changed, and we rely on many others to obtain the food we need. Some researchers believe that human survival and success depend more on how we deal with each other than how we deal with the natural world around us. - Culture as a Praxis

Controversy exists among anthropologists on whether culture should be understood more based on shared beliefs and values or on shared ways of doing things. Almost certainly, the answer is both. In the United States, for example, there is a shared value of democracy and of each individual having certain inalienable rights. We maintain this value by going to the voting booth on election day. A culture’s values and beliefs on aging and caring for the elderly are another example of a cultural praxis (a practice, as opposed to a theory). Some cultures may view aging as a decline in physical attractiveness, the ability to perform everyday tasks, and of cognitive ability. In contrast, other cultures view aging and the elderly as essential members of the group who should be respected for their increased wisdom and knowledge to be shared with others. In its broadest sense, culture can be described as cultivated behavior, that is, the totality of a person’s learned, accumulated experience, which is socially transmitted. More briefly, it can be described as behavior through social learning. - Culture as Information and Meaning

Another crucial aspect of culture is that it is based on meaningful information. Culture is acquired through the learning processes of enculturation and socialization. All cultures use language to encode and share information. People act as they do because they process this information. Their current actions are based on their thoughts about the future, including their goals and needs. Animals act mainly from instinct and learned responses without forming plans or thinking about the future. In contrast, humans’ actions are significantly influenced by their culture and their thoughts and beliefs about the future (whether it be one hour from now or a five-year plan). People formulate plans and goals and adjust their current behavior (adaptation) to help them reach these goals.

What, then, is culture? The different concepts covered in this section can be summarized in this way: Culture is an information-based system involving both shared understanding and praxis that allows groups of people to live together in an organized fashion.

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism In Group and Out Group (open YouTube video in new tab)

Ethnocentrism, in contrast to cultural relativism, is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of one’s own culture.

Ethnocentrism, a term coined by William Graham Sumner, is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of your own ethnic culture and the belief that that is the “right” way to look at the world. This leads to incorrect assumptions about others’ behavior based on your norms, values, and beliefs. For instance, reluctance or aversion to trying another culture’s cuisine is ethnocentric. Social scientists strive to treat cultural differences as neither inferior nor superior. That way, they can understand their research topics within the appropriate cultural context and simultaneously examine their biases and assumptions.

This approach is known as “cultural relativism.” Cultural relativism is the principle that a person’s beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual’s own culture. A key component of cultural relativism is the concept that nobody, not even researchers, comes from a neutral position. The way to deal with our own assumptions is not to pretend that they don’t exist but rather to acknowledge them and then use the awareness that we are not neutral to inform our conclusions.

When social psychologists research culture, they try to avoid making value judgments. This is known as value-free research and is considered an important approach to scientific objectivity. However, while objectivity is the goal, it isn’t easy to achieve. With this in mind, anthropologists have tried to empathize with the cultures they study. This has led to cultural relativism, the principle of regarding and valuing a culture’s practices from that culture’s point of view. It is a considerate and practical way to avoid hasty judgments. Take, for example, the common practice of same-sex friends in India walking in public while holding hands: this is a common behavior and a sign of connectedness between two people. In England, by contrast, holding hands is mainly limited to romantically involved couples and often suggests a sexual relationship. These are simply two different ways of understanding the meaning of holding hands. Someone who does not take a relativistic view might be tempted to see their own understanding of this behavior as superior and, perhaps, the foreign practice as being immoral.

In some cultures, it’s perfectly normal for same-sex friends to hold hands, while in others, hand-holding is restricted to romantically involved individuals only.

Even though cultural relativism promotes the appreciation of cultural differences, it can also be problematic. At its most extreme, it leaves no room for criticism of other cultures, even if certain cultural practices are horrific or harmful. Many practices have drawn criticism over the years. In Madagascar, for example, the famahidana funeral tradition includes bringing bodies out from tombs once every seven years, wrapping them in cloth, and dancing with them. Some people view this practice as disrespectful to the body of a deceased person.

Another example can be seen in the historical Indian practice of sati—the burning to death of widows on their deceased husband’s funeral pyre. This practice was outlawed by the British when they colonized India. Today, a debate rages about the ritual cutting of the genitals of children in a few Middle Eastern and African cultures. This same debate arises around the circumcision of baby boys in Western hospitals. When considering harmful cultural traditions, it can be patronizing to the point of bigotry to use cultural relativism as an excuse for avoiding debate. To assume that people from other cultures are neither mature enough nor responsible enough to consider criticism from the outside is demeaning.

Positive cultural relativism is the belief that the world would be a better place if everyone practiced some form of intercultural empathy and respect. This approach offers a potentially significant contribution to theories of cultural progress: to understand human behavior better, people should avoid adopting extreme views that block discussions about the basic morality or usefulness of cultural practices.

Cultural Universals

Often, a comparison of one culture to another will reveal noticeable differences. But all cultures also share common elements. Cultural universals are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies. One example of a cultural universal is the family unit: every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions varies. In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household. In these cultures, young adults continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household, or they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead. In the United States, by contrast, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit that consists of parents and their offspring. Other cultural universals include customs like funeral rites, weddings, and celebrations of births. However, each culture may view the ceremonies quite differently.

Anthropologist George Murdock first recognized the existence of cultural universals while studying systems of kinship around the world. Murdock found that cultural universals often revolve around basic human survival, such as finding food, clothing, and shelter, or around shared human experiences, such as birth and death or illness and healing. Through his research, Murdock identified other universals, including language and the concept of personal names. Interestingly, humor is a universal way to release tensions and create a sense of unity among people (Murdock, 1949).

Is Music a Cultural Universal?

Imagine that you are sitting in a theater, watching a film. The movie opens with the heroine sitting on a park bench with a grim expression. Cue the music. The first slow and mournful notes play in a minor key. As the melody continues, the heroine turns and sees a man walking toward her. The music slowly gets louder, and the dissonance of the chords sends a prickle of fear running down your spine. You sense that the heroine is in danger.

Now, imagine that you are watching the same movie but with a different soundtrack. As the scene opens, the music is soft and soothing, with a hint of sadness. You see the heroine sitting on the park bench and sense her loneliness. Suddenly, the music swells. The woman looks up and sees a man walking toward her. The music grows fuller, and the pace picks up. You feel your heart rise in your chest. This is a happy moment.

Music can evoke emotional responses. In television shows, movies, and even commercials, music elicits laughter, sadness, or fear. Are these types of musical cues cultural universals?

In 2009, a team of psychologists, led by Thomas Fritz of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, studied people’s reactions to music they’d never heard (Fritz et al., 2009). The research team traveled to Cameroon, Africa, and asked Mafa tribal members to listen to Western music. The tribe, isolated from Western culture, had no context or experience within which to interpret its music. Even so, as the tribal members listened to a Western piano piece, they could recognize three basic emotions: happiness, sadness, and fear. Music, it turns out, is a sort of universal language.

Researchers also found that music can foster a sense of wholeness within a group. Scientists who study the evolution of language have concluded that originally, language (an established component of group identity) and music were one (Darwin, 1871). Additionally, since music is mainly nonverbal, the sounds of music can cross societal boundaries more easily than words. Music allows people to connect, where language might be a more difficult barrier. As Fritz and his team found, music and the emotions it conveys can be cultural universals.

Symbols, Values & Norms: Crash Course Sociology #10 (YouTube video in new tab)

Symbols and Language

Humans, consciously and subconsciously, always strive to make sense of their world. Symbols—gestures, signs, objects, signals, words, marriage, rituals, etc.—help people understand that world and are cultural representations of reality. They provide clues to understanding experiences by conveying recognizable meanings shared by members of a culture. Symbols occur in different forms: verbal or nonverbal, written or unwritten. They can be anything that conveys a meaning, such as words on the page, drawings, pictures, and gestures. They can be material or nonmaterial. For example, a flag can be both material, as it is a physical object, and nonmaterial because it represents different meanings, such as patriotism or respect. Even the destruction of symbols is symbolic. Effigies representing public figures are burned to demonstrate anger at certain leaders. In 1989, crowds tore down the Berlin Wall [new tab], a decades-old symbol of the division between East and West Germany, communism, and capitalism.

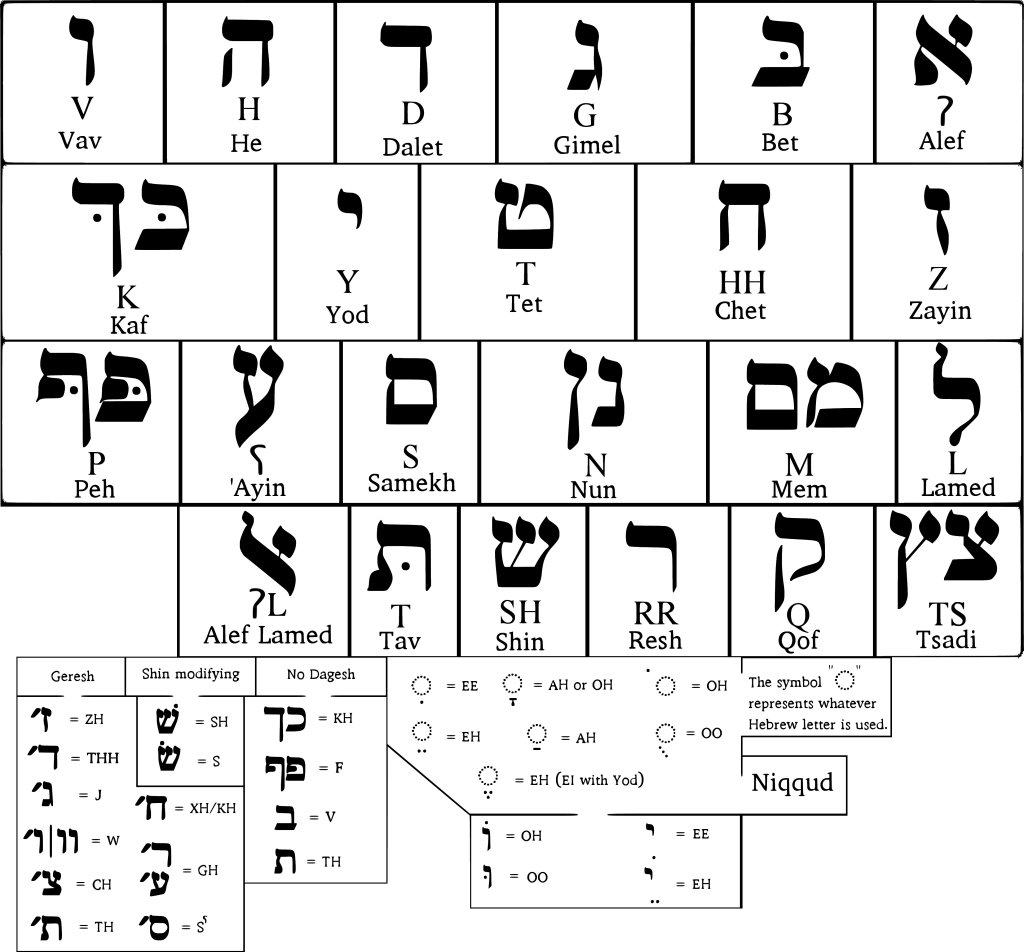

The Hebrew Alphabet: Cultures are shared systems of symbols and meanings. Alphabets are one example of a symbolic element of culture.

This view of culture argues that people living apart from one another develop unique cultures. Elements of different cultures, however, can easily spread from one group of people to another. The belief that culture is symbolically coded and can, therefore, be taught from one person to another means that cultures, although bounded, can change. Culture is dynamic and can be taught and learned, making it a potentially rapid form of adaptation to changes in physical conditions.

While different cultures have varying systems of symbols, one symbol is common to all: language. Language is a symbolic system through which people communicate and through which knowledge and culture is transmitted. Some languages contain a system of symbols used for written communication, while others rely on only spoken communication and nonverbal actions.

Rules for speaking and writing vary even within cultures, most notably by region. Do you refer to a can of carbonated liquid as “soda,” pop,” or “Coke”? Is a household entertainment room a “family room,” “rec room,” or “den”? When leaving a restaurant, do you ask your server for a “check,” the “ticket,” or your “bill”?

Language is constantly evolving as societies create new ideas. In this age of technology, people have adapted almost instantly to new nouns such as “e-mail” and “Internet” and verbs such as “downloading,” “texting,” and “posting.” Twenty years ago, the general public would have considered these nonsense words.

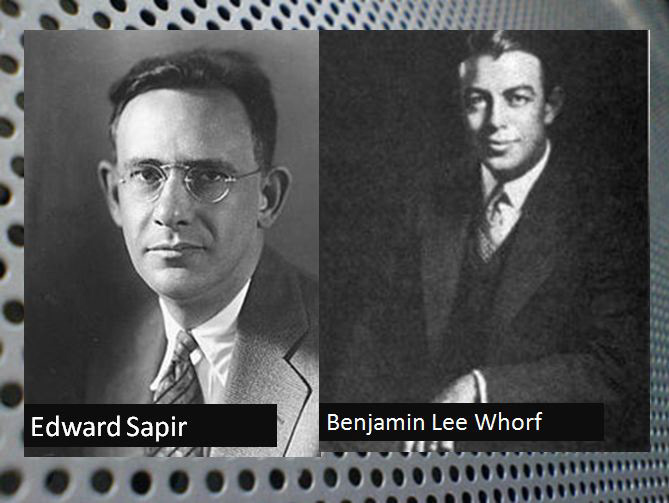

Even while it constantly evolves, language continues to shape our reality. This insight was established in the 1920s by two linguists, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. They believed that reality is culturally determined and that any interpretation of reality is based on a society’s language. To prove this point, the sociologists argued that every language has words or expressions specific to that language. In the United States, for example, the number thirteen is associated with bad luck. In Japan, however, the number four is considered unlucky since it is pronounced similarly to the Japanese word for “death.”

Language is traditionally thought to consist of three parts: signs, meanings, and a code connecting signs with their meanings. Semiotics studies how signs and meanings are combined, used, and interpreted. Signs can consist of sounds, gestures, letters, or symbols, depending on whether the language is spoken, signed, or written.

Language as a whole, therefore, is the human capacity for acquiring and using complex systems of communication. A single language is any specific example of such a system. Language is based on complex rules relating spoken, signed, or written symbols to their meanings. What results is an indefinite number of possible innovative utterances from a finite number of elements.

Human language is considered fundamentally different from and of much higher complexity than the communication systems of other species. Human language differs from communication used by animals because the symbols and grammatical rules of any particular language are largely arbitrary, meaning that the system can only be acquired through social interaction.

Media Attributions

- diversity © Gerd Altmann is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Close_the_door_(3484832603) © SnippyHolloW is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 40407262_5b79504415_w © Subharnab Majumdar is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Hebrew Alphabet © Assyrio is licensed under a Public Domain license

- a9ed6528716214.56053abcbe9c3 is licensed under a Public Domain license