5.2 Cognitive Processes

Introduction to the Processes of Cognition

Cognition is a fundamental aspect of psychology encompassing all the mental processes involved in acquiring, processing, storing, and using information. These processes are essential for everything we do, from simple tasks like recognizing a friend’s face to complex activities like solving mathematical problems or planning a vacation. Understanding cognition helps us appreciate how we perceive the world, make decisions, and interact with our environment.

What is Cognition?

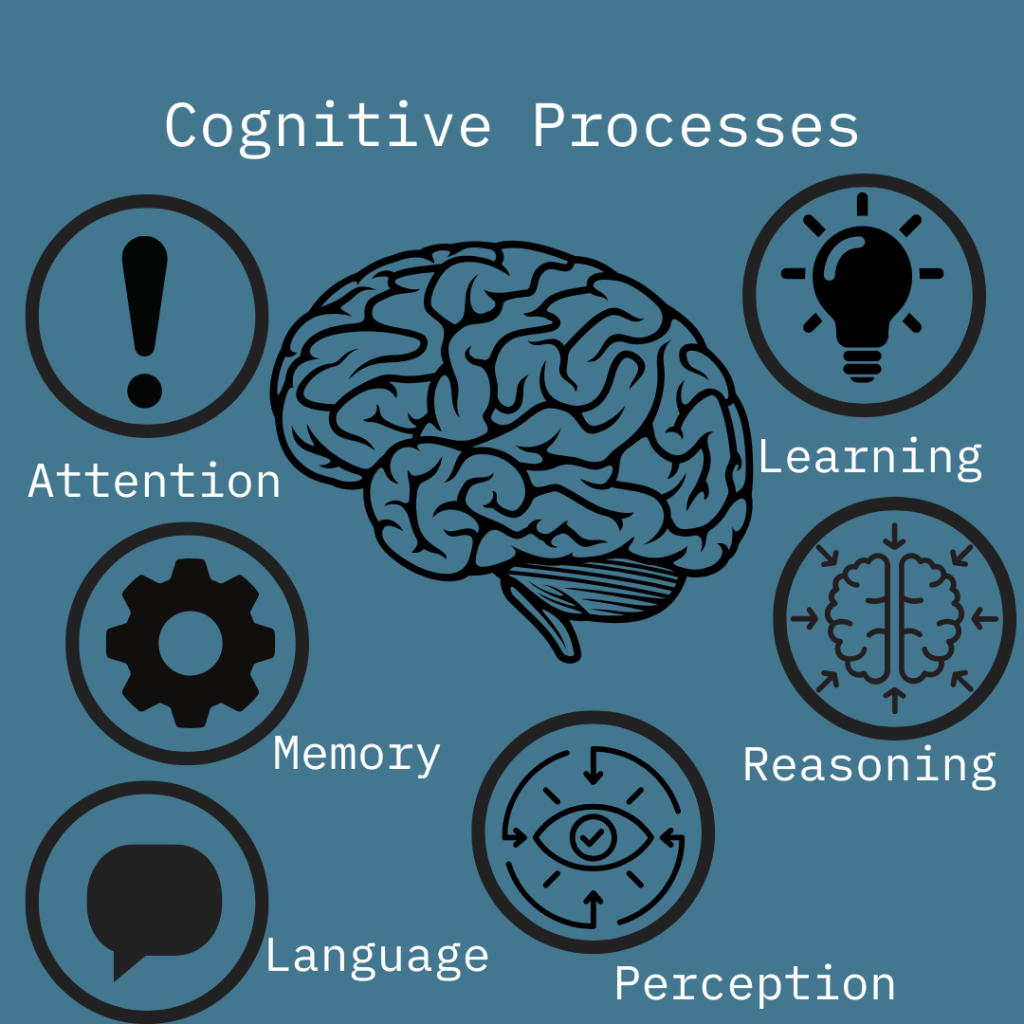

Cognition refers to the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating. It involves a wide range of processes, including:

- Perception: The process of organizing and interpreting sensory information to understand the environment.

- Attention: The ability to focus on specific stimuli or information while ignoring others.

- Memory: The storage and retrieval of information over time.

- Language: The use of symbols and rules to communicate thoughts and ideas.

- Problem-Solving: The process of finding solutions to difficult or complex issues.

- Decision-Making: The process of making choices among alternatives.

Attention as a Cognitive Process

We use the term “attention“ all the time, but what processes or abilities does that concept refer to? Here we focus on how attention allows us to select certain parts of our environment and ignore other parts, and what happens to the ignored information. A key concept is that we are limited in how much we can do at any one time.

Before we begin exploring attention in its various forms, take a moment to consider how you think about the concept. How would you define attention, or how do you use the term? We certainly use the word very frequently in our everyday language: “ATTENTION! USE ONLY AS DIRECTED!” warns the label on the medicine bottle, meaning be alert to possible danger. “Pay attention!” pleads the weary seventh-grade teacher, not warning about danger (with possible exceptions, depending on the teacher) but urging the students to focus on the task at hand. We may refer to a child easily distracted as having an attention disorder. However, we are also told that Americans have an attention span of about 8 seconds, down from 12 seconds in 2000, suggesting that we all have trouble sustaining concentration for any amount of time, according to a 2018 study by the Statistic Brain Research Institute. How that number was determined is not clear from the website, nor is it clear how the attention span in the goldfish—9 seconds!—was measured, but the fact that our average span reportedly is less than that of a goldfish is intriguing, to say the least.

William James wrote extensively about attention in the late 1800s. An often-quoted passage of his beautifully captures how intuitively obvious the concept of attention is, yet remains very difficult to define in measurable, concrete terms: “Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.”(from the text The Principles of Psychology)

Notice that this description touches on the conscious nature of attention and the notion that what is in consciousness is often controlled voluntarily but can also be determined by events that capture our attention. This description implies that we have a limited capacity for information processing and can only attend to or be consciously aware of a small amount of information at any given time.

Cultural Differences in Attention and Perception:

-

- Western Cultures: Tend to focus on salient, central objects in a scene. For example, Americans are likelier to concentrate on the main object in a picture, such as a train, and ignore the background details.

- Eastern Cultures: More likely to consider the context and relationships between objects. For instance, Chinese participants in studies often pay attention to both the main object and the background, reflecting a holistic view

Many aspects of attention have been studied in the field of psychology. In some respects, we define different types of attention by the nature of the task used to study it. For example, a crucial issue in World War II was how long an individual could remain highly alert and accurate while watching a radar screen for enemy planes, and this problem led psychologists to study how attention works under such conditions. When watching for a rare event, it is easy to allow concentration to lag. (This continues to be a challenge today for TSA agents, charged with looking at images of the contents of your carry-on items in search of knives, guns, or shampoo bottles larger than 3 oz.) Attention in the context of this type of search task refers to the level of sustained attention or vigilance one can maintain.

In contrast, divided attention tasks allow us to determine how well individuals can attend to many sources of information at once. Spatial attention refers to how we focus on one part of our environment and how we move attention to other locations. These are all examples of different aspects of attention, but an implied element of most of these ideas is the concept of selective attention; some information is attended to while others are intentionally blocked out.

See for yourself how unintentional blindness works. Check out this Selective Attention Test from Simons and Chabris (1999).

Selective Attention Test (open YouTube video in new tab)

Selective attention

Selective attention is the ability to select certain stimuli in the environment to process while ignoring distracting information. One way to get an intuitive sense of how attention works is to consider situations in which attention is used. A party provides an excellent example for our purposes. Many people may be milling around, there is a dazzling variety of colors, sounds, and smells, and the buzz of many conversations is striking. So many discussions are going on; how is it possible to select just one and follow it? You don’t have to look at the person talking; you may listen with great interest to some gossip while pretending not to hear. However, once you are conversing with someone, you quickly become aware that you cannot listen to other conversations simultaneously. You are also probably unaware of how tight your shoes feel or the smell of a nearby flower arrangement.

On the other hand, if someone behind you mentions your name, you typically notice it immediately and may start attending to that (much more interesting) conversation. This situation highlights an interesting set of observations. We have a fantastic ability to select and track one voice, visual object, etc., even when a million things are competing for our attention. Still, at the same time, we are limited in how much we can attend to at one time, suggesting that attention is crucial in selecting what is essential. How does it all work?

Memory as a Cognitive Process

Memory is a single term that reflects several different abilities: holding information briefly while working with it (working memory), remembering episodes of one’s life (episodic memory), and our general knowledge of facts of the world (semantic memory), among other types. Remembering episodes involves three processes: encoding information (learning it by perceiving it and relating it to past knowledge), storing it (maintaining it over time), and then retrieving it (accessing the information when needed). Failures can occur at any stage, leading to forgetting or having false memories. The key to improving one’s memory is to improve the encoding processes and use techniques that guarantee effective retrieval. Good encoding techniques include relating new information to what one already knows, forming mental images, and creating associations among information that needs to be remembered. The key to good retrieval is developing effective cues that lead the rememberer back to the encoded information. Classic mnemonic systems, known since the ancient Greeks and still used by some today, can vastly improve one’s memory abilities.

Watch and complete the interactive video below on the multi-store model:

The Multi-Store Model: How We Make Memories (open YouTube video in new tab)

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory stores information over long periods, ranging from a few hours to a lifetime. If we want to remember something tomorrow, we must consolidate it into long-term memory today. Long-term memory is the final, semi-permanent stage of memory. Unlike sensory and short-term memory, long-term memory has a theoretically infinite capacity, and information can remain there indefinitely. Long-term memory is also called reference memory because an individual must refer to the information in long-term memory when performing almost any task. Long-term memory can be broken down into two categories: explicit and implicit.

Explicit Memory

Explicit memory, also known as conscious or declarative memory, involves memory of facts, concepts, and events that require conscious recall of the information. In other words, the individual must actively think about retrieving the information from memory. This type of information is explicitly stored and retrieved—hence its name. Explicit memory can be subdivided into semantic memory, which concerns facts, and episodic memory, which primarily concerns personal or autobiographical information.

- Semantic memory involves abstract factual knowledge, such as “Albany is the capital of New York.” It is for the type of information that we learn from books and school: faces, places, facts, and concepts. You use semantic memory when you take a test. Another type of semantic memory is called a script. Scripts are like blueprints of what tends to happen in certain situations. For example, what usually happens if you visit a restaurant? You get the menu, order your meal, eat it, and then pay the bill. Through practice, you learn these scripts and encode them into semantic memory.

- Episodic memory is used for more contextualized memories. They are generally memories of specific moments or episodes in one’s life. As such, they include sensations and emotions associated with the event and the who, what, where, and when of what happened. An example of an episodic memory would be recalling your family’s trip to the beach. Autobiographical memory (memory for particular events in one’s life) is generally viewed as either equivalent to or a subset of episodic memory. One specific type of autobiographical memory is a flashbulb memory, a highly detailed, exceptionally vivid “snapshot” of the moment and circumstances in which a piece of surprising and consequential (or emotionally arousing) news was heard. For example, many people remember exactly where they were and what they were doing when they heard of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. This is because it is a flashbulb memory.

Semantic and episodic memory are closely related; memory for facts can be enhanced with episodic memories associated with the fact, and vice versa. For example, the answer to the factual question “Are all apples red?” might be recalled by remembering the time you saw someone eating a green apple. Likewise, semantic memories about specific topics, such as football, can contribute to more detailed episodic memories of a particular personal event, like watching a football game. A person who barely knows the rules of football will remember the various plays and outcomes of the game in much less detail than a football expert.

Implicit Memory

In contrast to explicit (conscious) memory, implicit (unconscious or procedural) memory involves procedures for completing actions. These actions develop with practice over time. Athletic skills are one example of implicit memory. You learn the fundamentals of a sport, practice them over and over, and then they flow naturally during a game. Rehearsing for a dance or musical performance is another example of implicit memory. Every day examples include remembering how to tie your shoes, drive a car, or ride a bicycle. These memories are accessed without conscious awareness—they are automatically translated into actions without us even realizing it. As such, they can often be challenging to teach or explain to other people. Implicit memories differ from the semantic scripts described above in that they usually involve movement and motor coordination, whereas scripts emphasize social norms or behaviors.

Knowing how to ride a bike is an example of procedural and implicit memory. Remembering your experience of riding it with your grandparents and having a great time draws on your explicit recollection of episodic memory.

Memory failures can occur at any stage, leading to forgetting or having false memories. The key to improving one’s memory is to improve the encoding processes and use techniques that guarantee effective retrieval. Good encoding techniques include relating new information to what one already knows, forming mental images, and creating associations among information that needs to be remembered. The key to good retrieval is developing effective cues that lead the person back to the encoded information. Classic mnemonic systems can significantly improve one’s memory abilities.

Culture and Memory

After learning about episodic memory, it should be evident that many memories are personal and unique to us. Still, cultural psychologists and researchers have found that the average age of first memories varies up to two years between different cultures. Researchers believe that enculturation and cultural values influence childhood memories. For example, how parents and other adults discuss or don’t discuss the events in children’s lives influences how the children will later remember those events.

Mullen (1994) found that Asian and Asian-American undergraduates’ memories, on average, happened six months later than the Caucasian students’ memories. These results were repeated in a sample of native Korean participants, but the differences were even more prominent this time. The difference between Caucasian participants and native Korean participants was almost 16 months. Hayne et al. (2000) also found that Asian adults’ first memories were later than Caucasians’, but Maori adults’ (native population from New Zealand) memories reached even further back to around age three. These results do not mean that Caucasians or Maoris have better memories than Asians, but rather, people have the types of memories they need to get along well in the world they inhabit – memories exist within a cultural context. For example, Maori culture is focused on personal history and stories to a greater degree than American culture and Asian culture. The values of individualistic and collectivist cultures could also explain differences in memory. Individualistic cultures tend to be independently oriented, emphasizing standing out and being unique. Interpersonal harmony and cohesion are the emphases of collectivist cultures, and how people connect is less often through sharing memories of personal events. In some cultures, personal memory isn’t nearly as important as it is for people from individualistic cultures.

Cultural Differences in Memory

- Western Cultures: Tend to remember individual items and specific details. For example, Americans might recall a list of unrelated words more accurately.

- Eastern Cultures: More likely to remember relationships and context. For instance, Chinese participants might better recall a story that includes social interactions and contextual details

Language and Learning as Cognitive Processes

Language and learning are interconnected cognitive processes that significantly influence how individuals perceive, interpret, and engage with the world around them. Language is a primary tool for encoding, retrieving, and expressing knowledge, playing a critical role in learning across contexts. Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory emphasizes that language is not just a means of communication but also a cognitive tool that shapes thinking and problem-solving. Through internal speech, individuals use language to guide their thoughts and actions, demonstrating its role in cognitive self-regulation. For example, when students articulate their reasoning during problem-solving tasks, they externalize cognitive processes, allowing for deeper understanding and reflection. This dynamic interaction between language and learning highlights the importance of linguistic development in fostering academic achievement and cognitive growth.

Cultural and linguistic diversity also impacts how language and learning intersect. Research indicates that bilingual and multilingual individuals often demonstrate enhanced cognitive flexibility and executive functioning due to their ability to navigate and switch between languages (Bialystok et al., 2012). This linguistic adaptability facilitates learning by promoting attention control and working memory. However, language can also pose challenges in learning environments, mainly when students are taught in a language that is not their first. Limited proficiency in the instructional language can impede comprehension, participation, and overall academic performance (Cummins, 2000). Educators can address this challenge by incorporating students’ native languages into instruction and leveraging linguistic resources to support learning and cognitive development. Recognizing the reciprocal relationship between language and learning is essential for creating equitable and inclusive educational practices that account for linguistic diversity.

Cultural context significantly influences how language and learning processes unfold. Different cultures prioritize various aspects of language, which in turn affects cognitive development. For example, Western cultures often emphasize analytical thinking and explicit instruction, leading to a focus on grammar and vocabulary in language education. In contrast, many Eastern cultures adopt a more holistic approach, integrating language learning with social and contextual cues (Nisbett, 2003). These cultural differences underscore the importance of cultural context in cognitive research and education. Understanding how language and learning processes vary across cultures can enhance educational practices and promote more effective communication in our increasingly globalized world.

Do we think differently in different languages? BBC Ideas (open YouTube video in new tab)

Further your knowledge by also reading one of these Psychology Today articles:

- How the Language We Speak Affects the Way We Think (2017) [New Tab]

- How the Language You Speak Influences the Way You Think (2018)[New Tab]

Problem Solving and Decision Making

Higher-order cognitive processes, such as problem-solving and decision-making, are deeply influenced by cultural differences, as cultural norms and values shape how individuals think, evaluate options, and prioritize goals. For example, individuals from individualistic cultures, such as the United States or Germany, often emphasize autonomy and personal achievement. This emphasis is reflected in an analytical thinking style, where decisions are made based on explicit rules or logical reasoning. For instance, a manager in the United States may approach a workplace problem by analyzing performance metrics and implementing a standardized solution without extensive consultation. In contrast, individuals from collectivistic cultures, such as Japan or China, prioritize group harmony and interconnectedness, demonstrating a holistic thinking style that considers context and relationships. For example, a manager in Japan may involve team members in a consensus-building process to ensure that the solution aligns with group values and minimizes conflict (Nisbett et al., 2001).

These differences extend to educational and interpersonal scenarios. Western education systems often encourage problem-solving through debate and argumentation, where students are rewarded for presenting unique ideas and challenging others. Conversely, in East Asian educational settings, students may approach problem-solving with an emphasis on collaboration and respect for authority, reflecting broader cultural values of hierarchy and harmony (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Additionally, these cultural patterns manifest in moral decision-making. Research shows that people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to prioritize ethical decisions that benefit the group, even at a personal cost. In contrast, those from individualistic cultures may emphasize justice or fairness based on universal principles (Triandis, 1995). Recognizing these cultural nuances is crucial in fostering effective cross-cultural communication, collaboration, and understanding in diverse, globalized environments.

Cultural Differences in Problem-Solving and Decision Making:

-

- Western Cultures: Prefer analytical approaches, breaking down problems into smaller parts and focusing on individual elements. This is evident in Western education systems, which emphasize critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Eastern Cultures: Favor holistic approaches, considering the problem as a whole and the relationships between its parts. Eastern education systems often emphasize group work and collective problem-solving

- Western Cultures: Decisions are often based on individual preferences and personal goals. For example, Americans might choose a career path based on personal interests and ambitions.

- Eastern Cultures: Decisions are more likely to consider the impact on the social group and relationships. For instance, Japanese individuals might choose a career that benefits their family or community

Media Attributions

- Creative Process © P. Crossman is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- pexels-chuchuphinh-1139672 © Chu Chup Hinh is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license