4 Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in its modern formulation has been an important and progressing topic since the 1950s. To be sure, evidences of businesses seeking to improve society, the community, or particular stakeholder groups may be traced back hundreds of years (Carroll et al. 2012). In this discussion, however, the emphasis will be placed on concepts and practices that have characterized the post-World War II era. Much of the literature addressing CSR and what it means began in the United States; however, evidences of its applications, often under different names, traditions, and rationales, has been appearing around the world. Today, Europe, Asia, Australia, Africa, South America, and many developing countries are increasingly embracing the idea in one form or another. Clearly, CSR is a concept that has endured and continues to grow in importance and impact.

To be fair, it must be acknowledged that some writers early on have been critical of the CSR concept. In an important Harvard Business Review article in 1958, for example, Theodore Levitt spoke of “The Dangers of Social Responsibility.” His position was best summarized when he stated that business has only two responsibilities – (1) to engage in face-to-face civility such as honesty and good faith and (2) to seek material gain. Levitt argued that long-run profit maximization is the one dominant objective of business, in practice as well as theory (Levitt 1958, p. 49). The most well-known adversary of social responsibility, however, is economist Milton Friedman who argued that social issues are not the concern of business people and that these problems should be resolved by the unfettered workings of the free market system (Friedman 1962).

Introduction

The modern era of CSR, or social responsibility as it was often called, is most appropriately marked by the publication by Howard R. Bowen of his landmark book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman in 1953. Bowen’s work proceeded from the belief that the several hundred largest businesses in the United States were vital centers of power and decision making and that the actions of these firms touched the lives of citizens in many ways. The key question that Bowen asked that continues to be asked today was “what responsibilities to society may businessmen reasonably be expected to assume?” (Bowen 1953, p. xi) As the title of Bowen’s book suggests, this was a period during which business women did not exist, or were minimal in number, and thus they were not acknowledged in formal writings. Things have changed significantly since then. Today there are countless business women and many of them are actively involved in CSR.

Much of the early emphasis on developing the CSR concept began in scholarly or academic circles. From a scholarly perspective, most of the early definitions of CSR and initial conceptual work about what it means in theory and in practice was begun in the 1960s by such writers as Keith Davis, Joseph McGuire, Adolph Berle, William Frederick, and Clarence Walton (Carroll 1999). Its’ evolving refinements and applications came later, especially after the important social movements of the 1960s, particularly the civil rights movement, consumer movement, environmental movement and women’s movements.

Dozens of definitions of corporate social responsibility have arisen since then. In one study published in 2006, Dahlsrud identified and analyzed 37 different definitions of CSR and his study did not capture all of them (Dahlsrud 2006).

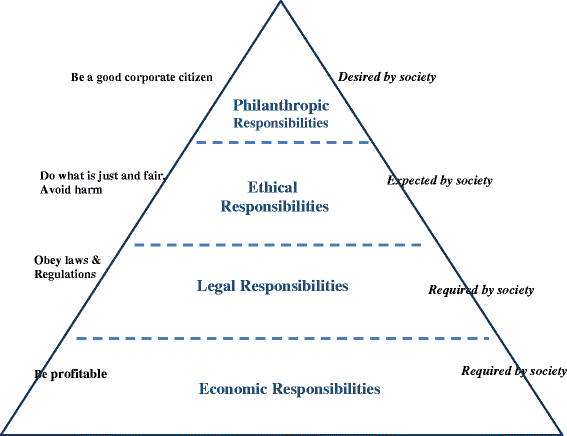

In this article, however, the goal is to revisit one of the more popular constructs of CSR that has been used in the literature and practice for several decades. Based on his four-part framework or definition of corporate social responsibility, Carroll created a graphic depiction of CSR in the form of a pyramid. CSR expert Dr. Wayne Visser has said that “Carroll’s CSR Pyramid is probably the most well-known model of CSR…” (Visser 2006). If one goes online to Google Images and searches for “Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR,” well over 100 variations and reproductions of the pyramidal model are presented there (Google Images) and over 5200 citations of the original article are indicated there (Google Scholar).

The purpose of the current commentary is to summarize the Pyramid of CSR, elaborate on it, and to discuss some aspects of the model that were not clarified when it was initially published in 1991. Twenty five years have passed since the initial publication of the CSR pyramid, but in early 2016 it still ranks as one of the most frequently downloaded articles during the previous 90 days in the journal in which it was published – (Elsevier Journals), Business Horizons (Friedman 1962) – sponsored by the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. Carroll’s four categories or domains of CSR, upon which the pyramid was established, have been utilized by a number of different theorists (Swanson 1995; Wartick and Cochran 1985; Wood 1991, and others) and empirical researchers (Aupperle 1984; Aupperle et al. 1985; Burton and Hegarty 1999; Clarkson 1995; Smith et al. 2001, and many others). According to Wood and Jones, Carroll’s four domains have “enjoyed wide popularity among SIM (Social Issues in Management) scholars (Wood and Jones 1996). Lee has said that the article in which the four part model of CSR was published has become “one of the most widely cited articles in the field of business and society” (Lee 2008). Thus, it is easy to see why a re-visitation of the pyramid based on the four category definition might make some sense and be useful.

Many of the early definitions of CSR were rather general. For example, in the 1960s it was defined as “seriously considering the impact of the company’s actions on society.” Another early definition of CSR read as follows: “Social responsibility is the obligation of decision makers to take actions which protect and improve the welfare of society along with their own interests” (Davis 1975). In general, CSR has typically been understood as policies and practices that business people employ to be sure that society, or stakeholders, other than business owners, are considered and protected in their strategies and operations. Some definitions of CSR have argued that an action must be purely voluntary to be considered socially responsible; others have argued that it embraces legal compliance as well; still others have argued that ethics is a part of CSR; virtually all definitions incorporate business giving or corporate philanthropy as a part of CSR and many observers equate CSR with philanthropy only and do not factor in these other categories of responsibility.

The ensuing discussion explains briefly each of the four categories that comprise Carroll’s four-part definitional framework upon which the pyramidal model is constructed.

The four-part definitional framework for CSR

Carroll’s four part definition of CSR was originally stated as follows: “Corporate social responsibility encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary (philanthropic) expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time” (Carroll 1979, 1991). This set of four responsibilities creates a foundation or infrastructure that helps to delineate in some detail and to frame or characterize the nature of businesses’ responsibilities to the society of which it is a part. In the first research study using the four categories it was found that the construct’s content validity and the instrument assessing it were valid (Aupperle et al. 1985). The study found that experts were capable of distinguishing among the four components. Further, the factor analysis conducted concluded that there are four empirically interrelated, but conceptually independent components of corporate social responsibility. This study also found that the relative values or weights of each of the components as implicitly depicted by Carroll approximated the relative degree of importance the 241 executives surveyed placed on the four components—economic = 3.5; legal = 2.54; ethical = 2.22; and discretionary/philanthropic = 1.30. Later research supported that Aupperle’s instrument measuring CSR using Carroll’s four categories (Aupperle 1984) was valid and useful (Edmondson and Carroll 1999; Pinkston and Carroll 1996 and others). In short, the distinctiveness and usefulness in research of the four categories have been established through a number of empirical research projects. A brief review of each of the four categories of CSR follows.

Economic responsibilities

As a fundamental condition or requirement of existence, businesses have an economic responsibility to the society that permitted them to be created and sustained. At first, it may seem unusual to think about an economic expectation as a social responsibility, but this is what it is because society expects, indeed requires, business organizations to be able to sustain themselves and the only way this is possible is by being profitable and able to incentivize owners or shareholders to invest and have enough resources to continue in operation. In its origins, society views business organizations as institutions that will produce and sell the goods and services it needs and desires. As an inducement, society allows businesses to take profits. Businesses create profits when they add value, and in doing this they benefit all the stakeholders of the business.

Profits are necessary both to reward investor/owners and also for business growth when profits are reinvested back into the business. CEOs, managers, and entrepreneurs will attest to the vital foundational importance of profitability and return on investment as motivators for business success. Virtually all economic systems of the world recognize the vital importance to the societies of businesses making profits. While thinking about its’ economic responsibilities, businesses employ many business concepts that are directed towards financial effectiveness – attention to revenues, cost-effectiveness, investments, marketing, strategies, operations, and a host of professional concepts focused on augmenting the long-term financial success of the organization. In today’s hypercompetitive global business environment, economic performance and sustainability have become urgent topics. Those firms that are not successful in their economic or financial sphere go out of business and any other responsibilities that may be incumbent upon them become moot considerations. Therefore, the economic responsibility is a baseline requirement that must be met in a competitive business world.

Legal responsibilities

Society has not only sanctioned businesses as economic entities, but it has also established the minimal ground rules under which businesses are expected to operate and function. These ground rules include laws and regulations and in effect reflect society’s view of “codified ethics” in that they articulate fundamental notions of fair business practices as established by lawmakers at federal, state and local levels. Businesses are expected and required to comply with these laws and regulations as a condition of operating. It is not an accident that compliance officers now occupy an important and high level position in company organization charts. While meeting these legal responsibilities, important expectations of business include their

- Performing in a manner consistent with expectations of government and law

- Complying with various federal, state, and local regulations

- Conducting themselves as law-abiding corporate citizens

- Fulfilling all their legal obligations to societal stakeholders

- Providing goods and services that at least meet minimal legal requirements

Ethical responsibilities

The normative expectations of most societies hold that laws are essential but not sufficient. In addition to what is required by laws and regulations, society expects businesses to operate and conduct their affairs in an ethical fashion. Taking on ethical responsibilities implies that organizations will embrace those activities, norms, standards and practices that even though they are not codified into law, are expected nonetheless. Part of the ethical expectation is that businesses will be responsive to the “spirit” of the law, not just the letter of the law. Another aspect of the ethical expectation is that businesses will conduct their affairs in a fair and objective fashion even in those cases when laws do not provide guidance or dictate courses of action. Thus, ethical responsibilities embrace those activities, standards, policies, and practices that are expected or prohibited by society even though they are not codified into law. The goal of these expectations is that businesses will be responsible for and responsive to the full range of norms, standards, values, principles, and expectations that reflect and honor what consumers, employees, owners and the community regard as consistent with respect to the protection of stakeholders’ moral rights. The distinction between legal and ethical expectations can often be tricky. Legal expectations certainly are based on ethical premises. But, ethical expectations carry these further. In essence, then, both contain a strong ethical dimension or character and the difference hinges upon the mandate society has given business through legal codification.

While meeting these ethical responsibilities, important expectations of business include their

- Performing in a manner consistent with expectations of societal mores and ethical norms

- Recognizing and respecting new or evolving ethical/moral norms adopted by society

- Preventing ethical norms from being compromised in order to achieve business goals

- Being good corporate citizens by doing what is expected morally or ethically

- Recognizing that business integrity and ethical behavior go beyond mere compliance with laws and regulations (Carroll 1991)

As an overlay to all that has been said about ethical responsibilities, it also should be clearly stated that in addition to society’s expectations regarding ethical performance, there are also the great, universal principles of moral philosophy such as rights, justice, and utilitarianism that also should inform and guide company decisions and practices.

Philanthropic responsibilities

Corporate philanthropy includes all forms of business giving. Corporate philanthropy embraces business’s voluntary or discretionary activities. Philanthropy or business giving may not be a responsibility in a literal sense, but it is normally expected by businesses today and is a part of the everyday expectations of the public. Certainly, the quantity and nature of these activities are voluntary or discretionary. They are guided by business’s desire to participate in social activities that are not mandated, not required by law, and not generally expected of business in an ethical sense. Having said that, some businesses do give partially out of an ethical motivation. That is, they want to do what is right for society. The public does have a sense that businesses will “give back,” and this constitutes the “expectation” aspect of the responsibility. When one examines the social contract between business and society today, it typically is found that the citizenry expects businesses to be good corporate citizens just as individuals are. To fulfill its perceived philanthropic responsibilities, companies engage in a variety of giving forms – gifts of monetary resources, product and service donations, volunteerism by employees and management, community development and any other discretionary contribution to the community or stakeholder groups that make up the community.

Although there is sometimes an altruistic motivation for business giving, most companies engage in philanthropy as a practical way to demonstrate their good citizenship. This is done to enhance or augment the company’s reputation and not necessarily for noble or self-sacrificing reasons. The primary difference between the ethical and philanthropic categories in the four part model is that business giving is not necessarily expected in a moral or ethical sense. Society expects such gifts, but it does not label companies as “unethical” based on their giving patterns or whether the companies are giving at the desired level. As a consequence, the philanthropic responsibility is more discretionary or voluntary on business’s part. Hence, this category is often thought of as good “corporate citizenship.” Having said all this, philanthropy historically has been one of the most important elements of CSR definitions and this continues today.

In summary, the four part CSR definition forms a conceptual framework that includes the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic or discretionary expectations that society places on businesses at a given point in time. And, in terms of understanding each type of responsibility, it could be said that the economic responsibility is “required” of business by society; the legal responsibility also is “required” of business by society; the ethical responsibility is “expected” of business by society; and the philanthropic responsibility is “expected/desired” of business by society (Carroll 1979, 1991). Also, as time passes what exactly each of these four categories means may change or evolve as well.

The Pyramid of CSR

The four-part definition of CSR was originally published in 1979. In 1991, Carroll extracted the four-part definition and recast it in the form of a CSR pyramid. The purpose of the pyramid was to single out the definitional aspect of CSR and to illustrate the building block nature of the four part framework. The pyramid was selected as a geometric design because it is simple, intuitive, and built to withstand the test of time. Consequently, the economic responsibility was placed as the base of the pyramid because it is a foundational requirement in business. Just as the footings of a building must be strong to support the entire edifice, sustained profitability must be strong to support society’s other expectations of enterprises. The point here is that the infrastructure of CSR is built upon the premise of an economically sound and sustainable business.

At the same time, society is conveying the message to business that it is expected to obey the law and comply with regulations because law and regulations are society’s codification of the basic ground rules upon which business is to operate in a civil society. If one looks at CSR in developing countries, for example, whether a legal and regulatory framework exists or not significantly affects whether multinationals invest there or not because such a legal infrastructure is imperative to provide a foundation for legitimate business growth.

In addition, business is expected to operate in an ethical fashion. This means that business has the expectation, and obligation, that it will do what is right, just, and fair and to avoid or minimize harm to all the stakeholders with whom it interacts. Finally, business is expected to be a good corporate citizen, that is, to give back and to contribute financial, physical, and human resources to the communities of which it is a part. In short, the pyramid is built in a fashion that reflects the fundamental roles played and expected by business in society. Figure 1 presents a graphical depiction of Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR.

Ethics permeates the pyramid

Though the ethical responsibility is depicted in the pyramid as a separate category of CSR, it should also be seen as a factor which cuts through and saturates the entire pyramid. Ethical considerations are present in each of the other responsibility categories as well. In the Economic Responsibility category, for example, the pyramid implicitly assumes a capitalistic society wherein the quest for profits is viewed as a legitimate, just expectation. Capitalism, in other words, is an economic system which thinks of it as being ethically appropriate that owners or shareholders merit a return on their investments. In the Legal Responsibility category, it should be acknowledged that most laws and regulations were created based upon some ethical reasoning that they were appropriate. Most laws grew out of ethical issues, e.g., a concern for consumer safety, employee safety, the natural environment, etc., and thus once formalized they represented “codified ethics” for that society. And, of course, the Ethical Responsibility stands on its own in the four part model as a category that embraces policies and practices that many see as residing at a higher level of expectation than the minimums required by law. Minimally speaking, law might be seen as passive compliance. Ethics, by contrast, suggests a level of conduct that might anticipate future laws and in any event strive to do that which is considered above most laws, that which is driven by rectitude. Finally, Philanthropic Responsibilities are sometimes ethically motivated by companies striving to do the right thing. Though some companies pursue philanthropic activities as a utilitarian decision (e.g., strategic philanthropy) just to be seen as “good corporate citizens,” some do pursue philanthropy because they consider it to be the virtuous thing to do. In this latter interpretation, philanthropy is seen to be ethically motivated or altruistic in nature (Schwartz and Carroll 2003). In summary, ethical motivations and issues cut through and permeate all four of the CSR categories and thus assume a vital role in the totality of CSR.

Tensions and trade-offs

As companies seek to adequately perform with respect to their economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities, tensions and trade-offs inevitably arise. How companies decide to balance these various responsibilities goes a long way towards defining their CSR orientation and reputation. The economic responsibility to owners or shareholders requires a careful trade-off between short term and long term profitability. In the short run, companies’ expenditures on legal, ethical and philanthropic obligations invariably will “appear” to conflict with their responsibilities to their shareholders. As companies expend resources on these responsibilities that appear to be in the primary interests of other stakeholders, a challenge to cut corners or seek out best long range advantages arises. This is when tensions and trade-offs arise. The traditional thought is that resources spent for legal, ethical and philanthropic purposes might necessarily detract from profitability. But, according to the “business case” for CSR, this is not a valid assumption or conclusion. For some time it has been the emerging view that social activity can and does lead to economic rewards and that business should attempt to create such a favorable situation (Chrisman and Carroll 1984).

The business case for CSR refers to the underlying arguments supporting or documenting why the business community should accept and advance the CSR cause. The business case is concerned with the primary question – What does the business community and commercial enterprises get out of CSR? That is, how do they benefit tangibly and directly from engaging in CSR policies, activities and practices (Carroll and Shabana 2010). There are many business case arguments that have been made in the literature, but four effective arguments have been made by Kurucz, et al., and these include cost and risk reductions, positive effects on competitive advantage, company legitimacy and reputation, and the role of CSR in creating win-win situations for the company and society (Kurucz et al. 2008). Other studies have enumerated the reasons for business to embrace CSR to include innovation, brand differentiation, employee engagement, and customer engagement. The purpose for business case thinking with respect to the Pyramid of CSR is to ameliorate the believed conflicts and tensions between and among the four categories of responsibilities. In short, the tensions and tradeoffs will continue to be important decision points, but they are not in complete opposition to one another as is often perceived.

The pyramid is an integrated, unified whole

The Pyramid of CSR is intended to be seen from a stakeholder perspective wherein the focus is on the whole not the different parts. The CSR pyramid holds that firms should engage in decisions, actions, policies and practices that simultaneously fulfill the four component parts. The pyramid should not be interpreted to mean that business is expected to fulfill its social responsibilities in some sequential, hierarchical, fashion, starting at the base. Rather, business is expected to fulfill all responsibilities simultaneously. The positioning or ordering of the four categories of responsibility strives to portray the fundamental or basic nature of these four categories to business’s existence in society. As said before, economic and legal responsibilities are required; ethical and philanthropic responsibilities are expected and desired. The representation being portrayed, therefore, is that the total social responsibility of business entails the concurrent fulfillment of the firm’s economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities. Stated in the form of an equation, it would read as follows: Economic Responsibilities + Legal responsibilities + Ethical Responsibilities + Philanthropic Responsibilities = Total Corporate Social Responsibility. Stated in more practical and managerial terms, the CSR driven firm should strive to make a profit, obey the law, engage in ethical practices and be a good corporate citizen. When seen in this way, the pyramid is viewed as a unified or integrated whole (Carroll and Buchholtz 2015).

The pyramid is a sustainable stakeholder framework

Each of the four components of responsibility addresses different stakeholders in terms of the varying priorities in which the stakeholders might be affected. Economic responsibilities most dramatically impact shareholders and employees because if the business is not financially viable both of these groups will be significantly affected. Legal responsibilities are certainly important with respect to owners, but in today’s litigious society, the threat of litigation against businesses arise most often from employees and consumer stakeholders. Ethical responsibilities affect all stakeholder groups. Shareholder lawsuits are an expanding category. When an examination of the ethical issues business faces today is considered, they typically involve employees, customers, and the environment most frequently. Finally, philanthropic responsibilities most affect the community and nonprofit organizations, but also employees because some research has concluded that a company’s philanthropic involvement is significantly related to its employees’ morale and engagement.

The pyramid should be seen as sustainable in that these responsibilities represent long term obligations that overarch into future generations of stakeholders as well. Though the pyramid could be perceived to be a static snapshot of responsibilities, it is intended to be seen as a dynamic, adaptable framework the content of which focuses both on the present and the future. A consideration of stakeholders and sustainability, today, is inseparable from CSR. Indeed, there have been some appeals in the literature for CSR to be redefined as Corporate Stakeholder Responsibility and others have advocated Corporate Sustainability Responsibilities. These appeals highlight the intimate nature of these interrelated topics (Carroll and Buchholtz 2015). Furthermore, Ethical Corporation Magazine which emphasizes CSR in its Responsible Summit conferences integrates these two topics – CSR and Sustainability—as if they were one and, in fact, many business organizations today perceive them in this way; that is, to be socially responsible is to invest in the importance of sustainability which implicitly is concerned with the future. Annual corporate social performance reports frequently go by the titles of CSR and/or Sustainability Reports but their contents are undifferentiated from one another; in other words, the concepts are being used interchangeably by many.

Global applicability and different contexts

When Carroll developed his original four-part construct of CSR (1979) and then his pyramidal depiction of CSR (1991), it was clearly done with American-type capitalistic societies in mind. At that time, CSR was most prevalent in these more free enterprise societies. Since that time, several writers have proposed that the pyramid needs to be reordered to meet the conditions of other countries or smaller businesses. In 2007, Crane and Matten observed that all the levels of CSR depicted in Carroll’s pyramid play a role in Europe but they have a dissimilar significance and are interlinked in a somewhat different manner (Crane and Matten 2007). Likewise, Visser revisited Carroll’s pyramid in developing countries/continents, in particular, Africa, and argued that the order of the CSR layers there differ from the classic pyramid. He goes on to say that in developing countries, economic responsibility continues to get the most emphasis, but philanthropy is given second highest priority followed by legal and then ethical responsibilities (Visser 2011). Visser continues to contend that there are myths about CSR in developing countries and that one of them is that “CSR is the same the world over.” Following this, he maintains that each region, country or community has a different set of drivers of CSR. Among the “glocal” (global + local) drivers of CSR, he suggests that cultural tradition, political reform, socio-economic priorities, governance gaps, and crisis response are among the most important (Visser 2011, p. 269). Crane, Matten and Spence do a nice job discussing CSR in a global context when they elaborate on CSR in different regions of the globe, CSR in developed countries, CSR in developing countries, and CSR in emerging/transitional economies (Crane et al. 2008).

In addition to issues being raised about the applicability of CSR and, therefore, the CSR pyramid in different localities, the same may be said for its applicability in different organizational contexts. Contexts of interest here might include private sector (large vs. small firms), public sector, and civil society organizations (Crane et al. 2008). In one particular theoretical article, Laura Spence sought to reframe Carroll’s CSR pyramid, enhancing its relevance for small business. Spence employed the ethic of care and feminist perspectives to redraw the four CSR domains by indicating that Carroll’s categories represented a masculinist perspective but that the ethic of care perspective would focus on different concerns. In this manner, she argued that the economic responsibility would be seen as “survival” in the ethic of care perspective; legal would be seen as “survival;” ethical would be recast as ethic of care; and philanthropy would continue to be philanthropy. It might be observed that these are not completely incompatible with Carroll’s categories. She then added a new category and that would be identified as “personal integrity.” She proposed that there could be at least four small business social responsibility pyramids – to self and family; to employees; to the local community; and to business partners (Spence 2016). Doubtless other researchers will continue to explore the applicability of the Pyramid of CSR to different global, situational, and organizational contexts. This is how theory and practice develops.

Conclusions

CSR has had a robust past and present. The future of CSR, whether it be viewed in the four part definitional construct, the Pyramid of CSR, or in some other format or nomenclature such as Corporate Citizenship, Sustainability, Stakeholder Management, Business Ethics, Creating Shared Value, Conscious Capitalism, or some other socially conscious semantics, seems to be on a sustainable and optimistic future. Though these other terminologies will sometimes be preferred by different supporters, CSR will continue to be the centerpiece of these competing and complementary frameworks (Carroll 2015). Though its enthusiasts would like to think of an optimistic or hopeful scenario wherein CSR would be adopted the world over and would be transformational everywhere it is practiced, the more probable scenario is that CSR will be consistent and stable and will continue to grow on a steady to slightly increasing trajectory. Four strong drivers of CSR taking hold in the 1990s and continuing forward have solidified its primacy. These include globalization, institutionalization, reconciliation with profitability, and academic proliferation (Carroll 2015b). Globally, countries have been quickly adopting CSR practices in both developed and developing regions. CSR as a management strategy has become commonplace, formalized, integrated, and deeply assimilated into organizational structures, policies and practices. Primarily via “business case” reasoning, CSR has been more quickly adopted as a beneficial practice both to companies and society. The fourth factor driving CSR’s growth trajectory has been academic acceptance, enthusiasm, and proliferation. There has been an explosion of rigorous theory building and research on the topic across many disciplines and this is expected to continue and grow. In short, CSR, the Pyramid of CSR, and related models and concepts face an upbeat and optimistic future. Those seeking to refine these concepts will continue to do so.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.