Chapter 11: Liquids and Solids

Learning Outcomes

- Define viscosity, surface tension, and capillary action

- Describe the roles of intermolecular attractive forces in each of these properties/phenomena

Viscosity

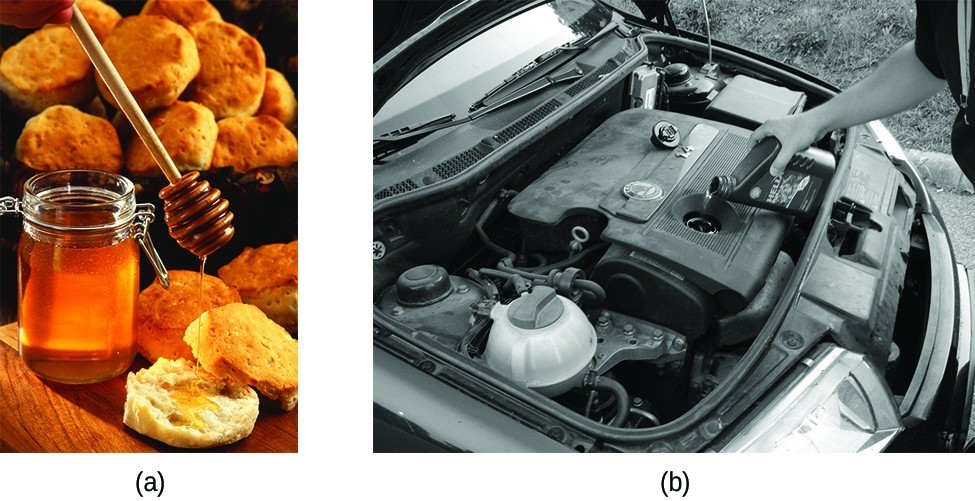

When you pour a glass of water, or fill a car with gasoline, you observe that water and gasoline flow freely. But when you pour syrup on pancakes or add oil to a car engine, you note that syrup and motor oil do not flow as readily. The viscosity of a liquid is a measure of its resistance to flow. Water, gasoline, and other liquids that flow freely have a low viscosity. Honey, syrup, motor oil, and other liquids that do not flow freely, like those shown in Figure 11.2.1, have higher viscosities. We can measure viscosity by measuring the rate at which a metal ball falls through a liquid (the ball falls more slowly through a more viscous liquid) or by measuring the rate at which a liquid flows through a narrow tube (more viscous liquids flow more slowly).

The IMFs between the molecules of a liquid, the size and shape of the molecules, and the temperature determine how easily a liquid flows. As Table 11.2.1 shows, the more structurally complex are the molecules in a liquid and the stronger the IMFs between them, the more difficult it is for them to move past each other and the greater is the viscosity of the liquid. As the temperature increases, the molecules move more rapidly and their kinetic energies are better able to overcome the forces that hold them together; thus, the viscosity of the liquid decreases.

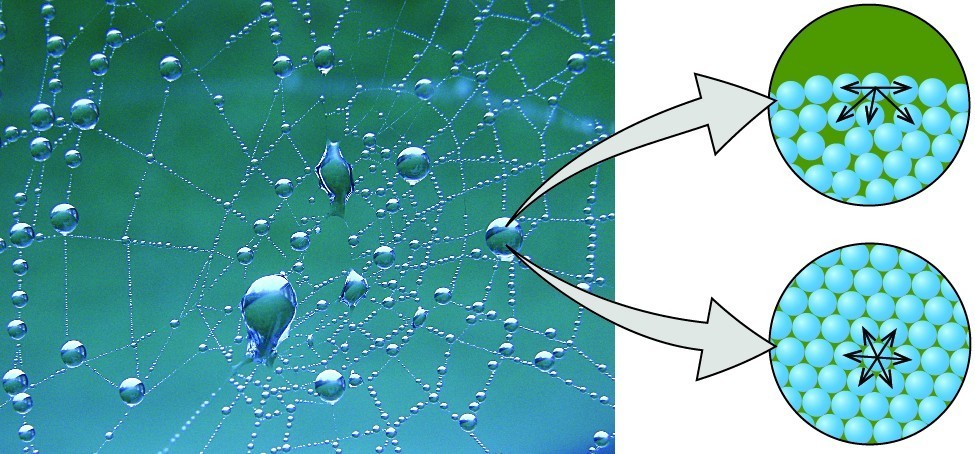

The various IMFs between identical molecules of a substance are examples of cohesive force. The molecules within a liquid are surrounded by other molecules and are attracted equally in all directions by the cohesive forces within the liquid. However, the molecules on the surface of a liquid are attracted only by about one-half as many molecules. Because of the unbalanced molecular attractions on the surface molecules, liquids contract to form a shape that minimizes the number of molecules on the surface—that is, the shape with the minimum surface area. A small drop of liquid tends to assume a spherical shape, as shown in Figure 11.2.2, because in a sphere, the ratio of surface area to volume is at a minimum. Larger drops are more greatly affected by gravity, air resistance, surface interactions, and so on, and as a result, are less spherical.

Surface Tension

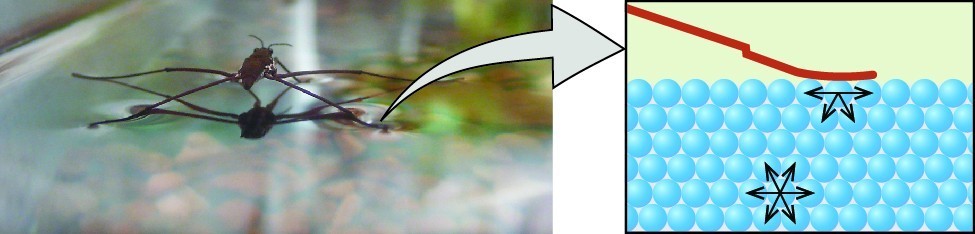

Surface tension is defined as the energy required to increase the surface area of a liquid, or the force required to increase the length of a liquid surface by a given amount. This property results from the cohesive forces between molecules at the surface of a liquid, and it causes the surface of a liquid to behave like a stretched rubber membrane. Surface tensions of several liquids are presented in Table 11.2.2.

Among common liquids, water exhibits a distinctly high surface tension due to strong hydrogen bonding between its molecules. As a result of this high surface tension, the surface of water represents a relatively “tough skin” that can withstand considerable force without breaking. A steel needle carefully placed on water will float. Some insects, like the one shown in Figure 11.2.3, even though they are denser than water, move on its surface because they are supported by the surface tension.

Capillary Action

The IMFs of attraction between two different molecules are called adhesive force. Consider what happens when water comes into contact with some surface. If the adhesive forces between water molecules and the molecules of the surface are weak compared to the cohesive forces between the water molecules, the water does not “wet” the surface.

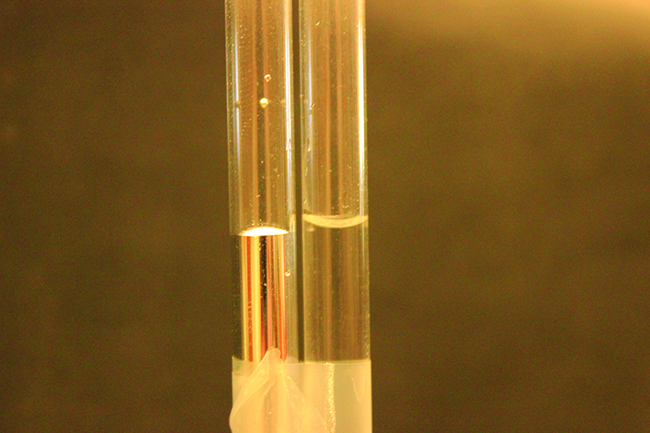

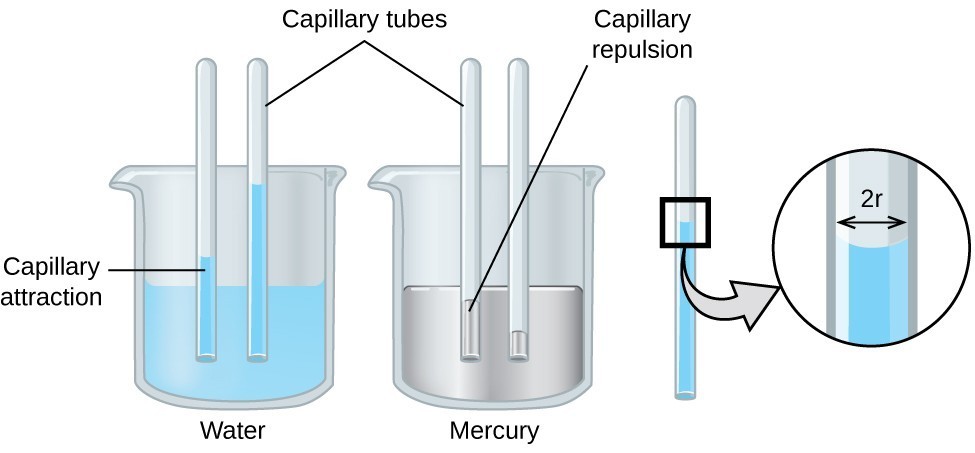

For example, water does not wet waxed surfaces or many plastics such as polyethylene. Water forms drops on these surfaces because the cohesive forces within the drops are greater than the adhesive forces between the water and the plastic. Water spreads out on glass because the adhesive force between water and glass is greater than the cohesive forces within the water. When water is confined in a glass tube, its meniscus (surface) has a concave shape because the water wets the glass and creeps up the side of the tube. On the other hand, the cohesive forces between mercury atoms are much greater than the adhesive forces between mercury and glass. Mercury therefore does not wet glass, and it forms a convex meniscus when confined in a tube because the cohesive forces within the mercury tend to draw it into a drop (Figure 11.2.4).

If you place one end of a paper towel in spilled wine, as shown in Figure 11.2.5, the liquid wicks up the paper towel. A similar process occurs in a cloth towel when you use it to dry off after a shower. These are examples of capillary action—when a liquid flows within a porous material due to the attraction of the liquid molecules to the surface of the material and to other liquid molecules. The adhesive forces between the liquid and the porous material, combined with the cohesive forces within the liquid, may be strong enough to move the liquid upward against gravity.

Towels soak up liquids like water because the fibers of a towel are made of molecules that are attracted to water molecules. Most cloth towels are made of cotton, and paper towels are generally made from paper pulp. Both consist of long molecules of cellulose that contain many [latex]\ce{-OH}[/latex] groups. Water molecules are attracted to these [latex]\ce{-OH}[/latex] groups and form hydrogen bonds with them, which draws the [latex]\ce{H2O}[/latex] molecules up the cellulose molecules. The water molecules are also attracted to each other, so large amounts of water are drawn up the cellulose fibers.

Capillary action can also occur when one end of a small diameter tube is immersed in a liquid, as illustrated in Figure 11.2.6. If the liquid molecules are strongly attracted to the tube molecules, the liquid creeps up the inside of the tube until the weight of the liquid and the adhesive forces are in balance. The smaller the diameter of the tube is, the higher the liquid climbs. It is partly by capillary action occurring in plant cells called xylem that water and dissolved nutrients are brought from the soil up through the roots and into a plant. Capillary action is the basis for thin layer chromatography, a laboratory technique commonly used to separate small quantities of mixtures. You depend on a constant supply of tears to keep your eyes lubricated and on capillary action to pump tear fluid away.

The height to which a liquid will rise in a capillary tube is determined by several factors as shown in the following equation:

[latex]\displaystyle{h=\dfrac{2T\text{cos}\theta }{r\rho g}}[/latex]

In this equation, h is the height of the liquid inside the capillary tube relative to the surface of the liquid outside the tube, T is the surface tension of the liquid, [latex]\theta[/latex] is the contact angle between the liquid and the tube, r is the radius of the tube, ρ is the density of the liquid, and g is the acceleration due to gravity, 9.8 m/s2. When the tube is made of a material to which the liquid molecules are strongly attracted, they will spread out completely on the surface, which corresponds to a contact angle of 0°. This is the situation for water rising in a glass tube.

Example 11.2.1: Capillary Rise

At 25 °C, how high will water rise in a glass capillary tube with an inner diameter of 0.25 mm?

For water, T = 71.99 mN/m and ρ = 1.0 g/cm3.

[reveal-answer q=”84129″]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a=”84129″]

The liquid will rise to a height h given by: [latex]h=\dfrac{2T\text{cos}\theta }{r\rho g}[/latex]

The Newton is defined as a kg m/s2, and so the provided surface tension is equivalent to 0.07199 kg/s2. The provided density must be converted into units that will cancel appropriately: ρ = 1000 kg/m3. The diameter of the tube in meters is 0.00025 m, so the radius is 0.000125 m. For a glass tube immersed in water, the contact angle is [latex]\theta[/latex]= 0°, so cos[latex]\theta[/latex] = 1. Finally, acceleration due to gravity on the earth is g = 9.8 m/s2. Substituting these values into the equation, and cancelling units, we have:

[latex]h=\dfrac{2\left(0.07199{\text{kg/s}}^{2}\right)}{\left(0.000125\text{m}\right)\left(1000{\text{kg/m}}^{3}\right)\left(9.8{\text{m/s}}^{2}\right)}=0.12\text{m}=\text{12 cm}[/latex]

[/hidden-answer]

Check Your Learning

Key Concepts and Summary

The intermolecular forces between molecules in the liquid state vary depending upon their chemical identities and result in corresponding variations in various physical properties. Cohesive forces between like molecules are responsible for a liquid’s viscosity (resistance to flow) and surface tension (elasticity of a liquid surface). Adhesive forces between the molecules of a liquid and different molecules composing a surface in contact with the liquid are responsible for phenomena such as surface wetting and capillary rise.

Key Equations

- [latex]h=\dfrac{2T\text{cos}\theta }{r\rho g}[/latex]

Try It

- The surface tension and viscosity values for diethyl ether, acetone, ethanol, and ethylene glycol are shown here.

- Explain their differences in viscosity in terms of the size and shape of their molecules and their IMFs.

- Explain their differences in surface tension in terms of the size and shape of their molecules and their IMFs.

[reveal-answer q=”334226″]Show Selected Solutions[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a=”334226″]

[/hidden-answer]

Glossary

adhesive force: force of attraction between molecules of different chemical identities

capillary action: flow of liquid within a porous material due to the attraction of the liquid molecules to the surface of the material and to other liquid molecules

cohesive force: force of attraction between identical molecules

surface tension: energy required to increase the area, or length, of a liquid surface by a given amount

viscosity: measure of a liquid’s resistance to flow

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Chemistry 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/1-introduction

All rights reserved content

- Surface tension | States of matter and intermolecular forces | Chemistry | Khan Academy. Authored by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://youtu.be/_RTF0DAHBBM. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Capillary action and why we see a meniscus | Chemistry | Khan Academy. Authored by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://youtu.be/eQXGpturk3A. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

measure of a liquid’s resistance to flow

force of attraction between identical molecules

energy required to increase the area, or length, of a liquid surface by a given amount

force of attraction between molecules of different chemical identities

flow of liquid within a porous material due to the attraction of the liquid molecules to the surface of the material and to other liquid molecules