3.1 The Nature of Language

Learning Objectives

- Explain how the triangle of meaning describes the symbolic nature of language.

- Discuss the function of the rules of language.

Language helps us understand others’ wants, needs, and desires. Language can help create connections, but it can also pull us apart. Language is so vital to communication. Imagine if you never learned a language; how would you be able to function? Without language, how could you develop meaningful connections with others? Language allows us to express ourselves and obtain our goals. Language is a system of human communication using a particular form of spoken or written words or other symbols. Language consists of the use of words in a structured way. Of course, words aren’t the only things we need to communicate, and although verbal and nonverbal communication are closely related in terms of how we make meaning, we separate verbal and nonverbal communication in this text so that we can examine the unique qualities individually. This process is essential in understanding how they work together to generate meaning.

The relationship between language and meaning is not a straightforward one. One reason for this complicated relationship is the limitlessness of modern language systems like English (Crystal, 2005). There are an infinite number of utterances we can make by connecting existing words in new ways. In addition, there is no limit to a language’s vocabulary, as new words are coined daily. You’ll recall that “generating meaning” was a central part of the definition of communication we learned earlier. We arrive at meaning through the interaction between our nervous and sensory systems and some stimulus outside them. Here, between what the communication models we discussed earlier labeled as encoding and decoding, that meaning is generated as sensory information is interpreted. The indirect and sometimes complicated relationship between language and meaning can lead to confusion, frustration, or maybe humor. We may even experience a little of all three when we stop to think about how there are some twenty-five definitions available to tell us the meaning of the word meaning (Crystal, 2005). Since language and symbols are the primary vehicles for our communication, it is important that we not take the components of our verbal communication for granted.

Language Is Symbolic

Our language system is primarily made up of symbols. A symbol is something that stands in for or represents something else. Symbols can be communicated verbally (speaking the word hello) or in writing (putting the letters H-E-L-L-O together). In any case, the symbols we use stand in for something else, like a physical object or an idea; they do not actually correspond to the thing being referenced in any direct way. Unlike hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt, which often did have a literal relationship between the written symbol and the object being referenced, the symbols used in modern languages look nothing like the object or idea to which they refer. For instance, someone along the way decided to call a computer a computer. It could have just as easily been named a pen, but it was named a computer. Now, when I refer to my computer, we all know I am referring to the technological device I use to do work, homework, shop on Amazon, etc.

The triangle of meaning is a model of communication that indicates the relationship between a thought, symbol, and referent and highlights the indirect relationship between the symbol and referent (Richards & Ogden, 1923). A thought is a concept or idea a person references. The symbol is the word that represents the thought, and the referent is the object or idea to which the symbol refers. This model is useful because when we are aware of the indirect relationship between symbols and referents, we know how common misunderstandings occur.

The following video explains the triangle of meaning.

Being aware of the indirect relationship between symbol and referent, we can try to compensate for it by getting clarification. Some of what we learned in chapter 2 about perception checking can be useful here. Sam might ask Max questions such as, “What kind of dog do you have in mind?” This question would allow Max to describe their referent, which would allow for a more shared understanding. If Max responds, “Well, I like short-haired dogs. And we need a dog that will work well in an apartment,” then there’s still quite a range of referents. Sam could ask questions for clarification, like “Sounds like you’re saying that a smaller dog might be better. Is that right?” Unfortunately, getting to a place of shared understanding can be difficult, even when we define our symbols and describe our referents.

Language is Learned

The relationship between the symbols that make up our language and their referents is arbitrary, which means they have no meaning until we assign that meaning. To effectively use a language system, we have to learn, over time, which symbols go with which referents since we can’t just tell by looking at the symbol. Like me, you probably learned what the word apple meant by looking at the letters A-P-P-L-E and a picture of an apple and having a teacher or caregiver help you sound out the letters until you said the whole word. Over time, we associated that combination of letters with the picture of the red delicious apple and no longer had to sound each letter out. This is a deliberate process that may seem slow in the moment, but as we will see next, our ability to acquire language is actually quite astounding. We didn’t just learn individual words and their meanings, though; we also learned rules of grammar that help us put those words into meaningful sentences.

The relationship between the symbols that make up our language and their referents is arbitrary, which means they have no meaning until we assign that meaning. To effectively use a language system, we have to learn, over time, which symbols go with which referents since we can’t just tell by looking at the symbol. Like me, you probably learned what the word apple meant by looking at the letters A-P-P-L-E and a picture of an apple and having a teacher or caregiver help you sound out the letters until you said the whole word. Over time, we associated that combination of letters with the picture of the red delicious apple and no longer had to sound each letter out. This is a deliberate process that may seem slow in the moment, but as we will see next, our ability to acquire language is actually quite astounding. We didn’t just learn individual words and their meanings, though; we also learned rules of grammar that help us put those words into meaningful sentences.

Language Rules

Semantic Rules

First, semantic rules refer to the meanings of words. They are rules that people have agreed on to give meaning to certain symbols and words. However, the meaning of a word can change based on the context in which it is used. For instance, the word fly by itself does not mean anything. It makes more sense if we put the word into a context by saying things like, “There is a fly on the wall;” “I will fly to Dallas tomorrow;” “That girl is so fly;” or “The fly on your pants is open!” We would not be able to communicate with others if we did not have semantic rules.

Definitions help us narrow the meaning of particular symbols, which also narrows a symbol’s possible referents. They also provide more words (symbols) for which we must determine a referent. If a concept is abstract and the words used to define it are also abstract, then a definition may be useless. Have you ever been caught in a verbal maze as you look up an unfamiliar word, only to find that the definition contains more unfamiliar words? Although this can be frustrating, definitions do serve a purpose.

However, using words is not as simple as using the dictionary definition of a word. Words have denotative and connotative meanings. Denotation refers to definitions accepted by the language group as a whole, or the dictionary definition of a word. For example, the denotation of the word cowboy is a man who cares for cattle. Another denotation is a reckless and/or independent person (Dictonary.com). A more abstract word, like change, would be more difficult to understand due to the multiple denotations. Since both cowboy and change have multiple meanings, they are considered polysemic words. Monosemic words have only one use in a language (or definition), which makes their denotation a bit more straightforward.

Semantic misunderstandings may arise when people give different meanings to the same words or phrases. Connotation refers to definitions based on emotion – or experience-based associations people have with a word. To go back to our previous words, change can have positive or negative connotations depending on a person’s experiences. A person who just ended a long-term relationship may think of change as good or bad depending on what they thought about their former partner. Even monosemic words like handkerchief that only have one denotation can have multiple connotations. A handkerchief can conjure up thoughts of dainty Southern belles or disgusting snot-rags. A polysemic word like cowboy has many connotations, and philosophers of language have explored how connotations extend beyond one or two experiential or emotional meanings of a word to constitute cultural myths (Barthes, 1972). Cowboy, for example, connects to the frontier and the western history of the United States, which has mythologies associated with it that help shape the narrative of the nation. While people who grew up with cattle or have families that ranch may have a very specific connotation of the word cowboy based on personal experience, other people’s connotations may be more influenced by popular cultural symbolism like that seen in westerns.

Syntactic Rules

Second, syntactic rules govern how we help guide the words we use. Syntactic rules can refer to the use of grammar, structure, and punctuation to help effectively convey our ideas. For instance, when we want to know where someone is, we may say, “Where are you” instead of “where you are.” Both of these statements convey different meanings and create different interpretations. The same thing can happen when you don’t place a comma correctly. The comma can make a big difference in how people understand a message.

A great example of how syntactic rules is the Star Wars character, Yoda, who often speaks with different rules. He has said, “Named must be your fear before banish it you can” and “The greatest teacher, failure is.” This example illustrates that syntactic rules can vary based on culture or background.

Pragmatic Rules

Third, pragmatic rules help us interpret messages by analyzing the interaction completely. We need to consider the words used, how they are stated, our relationship with the speaker, and the objectives of our communication. For instance, the words “I want to see you now” would mean different things if the speaker was your boss versus your romantic partner. One could be a positive connotation, and another might be a negative one. The same holds true for humor. If we know that the other person understands and appreciates sarcasm, we might be more likely to engage in that behavior and perceive it differently from someone who takes every word literally.

Most pragmatic rules are based on culture and experience. For instance, the term “Netflix and chill” has been used to indicate that two people will hook up. Imagine someone from a different country who did not know what this meant; they would be shocked if they thought they were going to watch Netflix with the other person and just relax. Another example would be “Want to have a drink?”, which usually infers an alcoholic beverage. Another way of saying this might be to say, “Would you like something to drink?” The second sentence does not imply that the drink has to contain alcohol.

It is common for people to text in capital letters when they are angry or excited. You would interpret the text differently if the text was not in capital letters. For instance, “I love you” might be perceived differently from “I LOVE YOU!!!” Thus, when communicating with others, you should also realize that pragmatic rules can impact the message.

Because language is symbolic, these rules help us to learn how to use language in a way that helps us to communicate with others. Unfortunately, we still experience many misunderstandings! The rest of this chapter will explore challenges we face and suggestions to improve your use of language.

Language can be Abstract or Concrete

When we think of language, it can be pretty abstract. For example, when we say something is “interesting,” it can be positive or negative. That is what we mean when we say that language is abstract. Language can be very specific. You can tell someone specific things to help them better understand what you are trying to say by using specific and concrete examples. For instance, if you say, “You are a jerk!” the person who receives that message might get pretty angry and wonder why you said that statement. To be clear, it might be better to say something like, “When you slammed that door in my face this morning, it really upset me, and I didn’t think that behavior was appropriate.” The second statement is more descriptive.

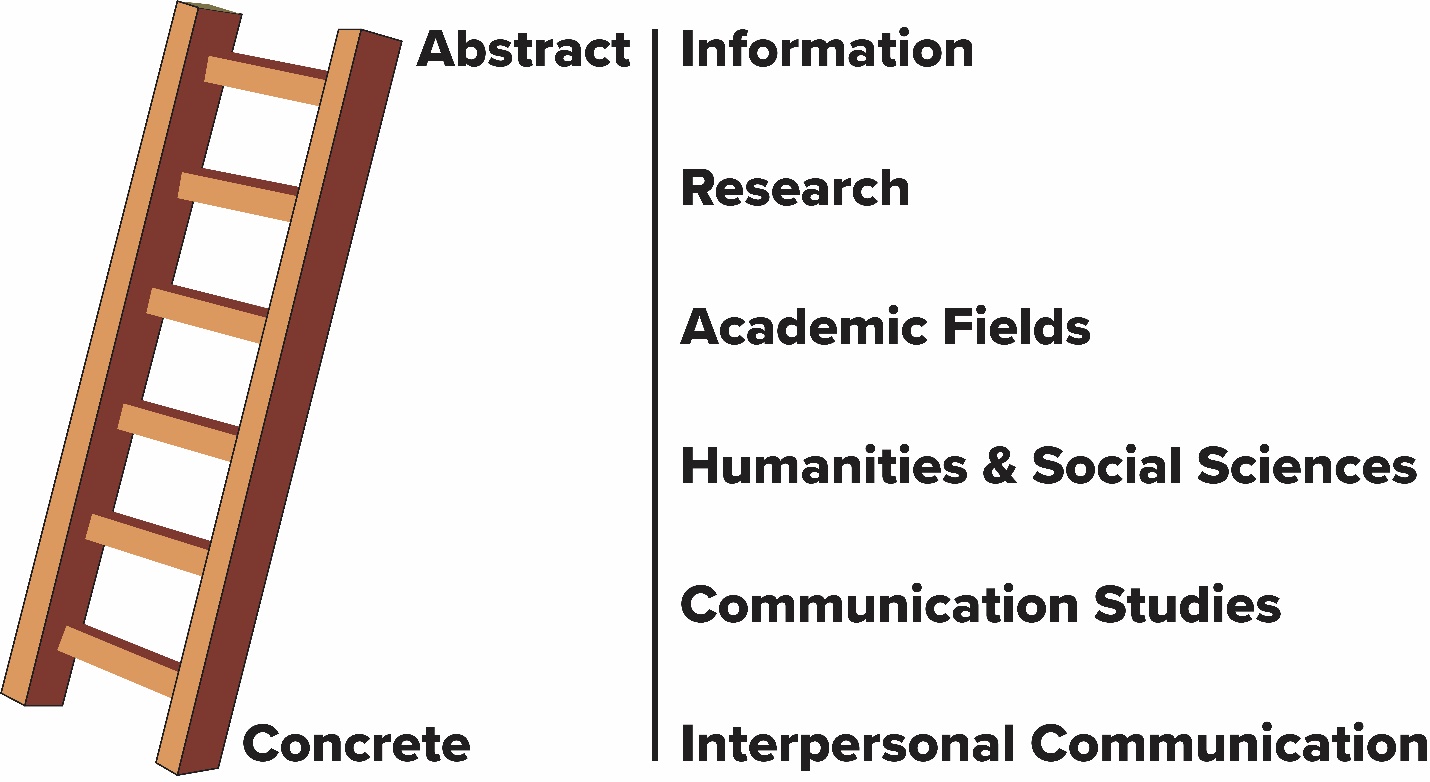

In 1941, linguist S.I. Hayakawa created what is called the abstraction ladder (Figure 3.1.2) (Hayakawa, 1941). The abstraction ladder starts abstract at the top, while the bottom rung is very concrete. In Figure 3.1.2, we’ve shown how you can go from abstract ideas (e.g., information) through various levels of more concrete ideas down to the most concrete idea (e.g., interpersonal communication). Ideally, you can see that as we move down the ladder, the topic becomes more fine-tuned and concrete.

In our daily lives, we tend to use high levels of abstraction all the time. For instance, growing up, your parents/guardians probably helped you with homework, cleaning, cooking, and transporting you from one event to another. Yet, we don’t typically say thank you to everything; we might make a general comment, such as a thank you, rather than saying, “Thank you so much for helping me with my math homework and helping me figure out how to solve for the volume of spheres.” It takes too long to say that, so people tend to be abstract. However, abstraction can cause problems if you don’t provide enough description.

Key Takeaways

- The triangle of meaning is a model of communication that indicates the relationship among a thought, symbol, and referent, and highlights the indirect relationship between the symbol and the referent. The model explains how for any given symbol there can be many different referents, which can lead to misunderstanding.

- Denotation refers to the agreed on or dictionary definition of a word. Connotation refers to definitions that are based on emotion- or experience-based associations people have with a word.

- The rules of language help make it learnable and usable. Although the rules limit some of the uses of language, they still allow for the possibility of creativity and play.

References

Barthes, R., Mythologies (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1972).

Crystal, D., How Language Works: How Babies Babble, Words Change Meaning, and Languages Live or Die (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2005), 8–9.

de Saussure, F., Course in General Linguistics, trans. Wade Baskin (London: Fontana/Collins, 1974).

Derrida, J., Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (London: Routledge, 1978).

Eco, U., A Theory of Semiotics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1976).

Hayakawa, S. I. and Alan R. Hayakawa, Language in Thought and Action, 5th ed. (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace, 1990), 87.

How Words Work. (2021, August 6). Retrieved August 9, 2021, from https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@go/page/115935

Leeds-Hurwitz, W., Semiotics and Communication: Signs, Codes, Cultures (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993), 53.

Richards, I. A. and Charles K. Ogden, The Meaning of Meaning (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Tubner, 1923).