61 8.10 Wh-Movement

Check Yourself

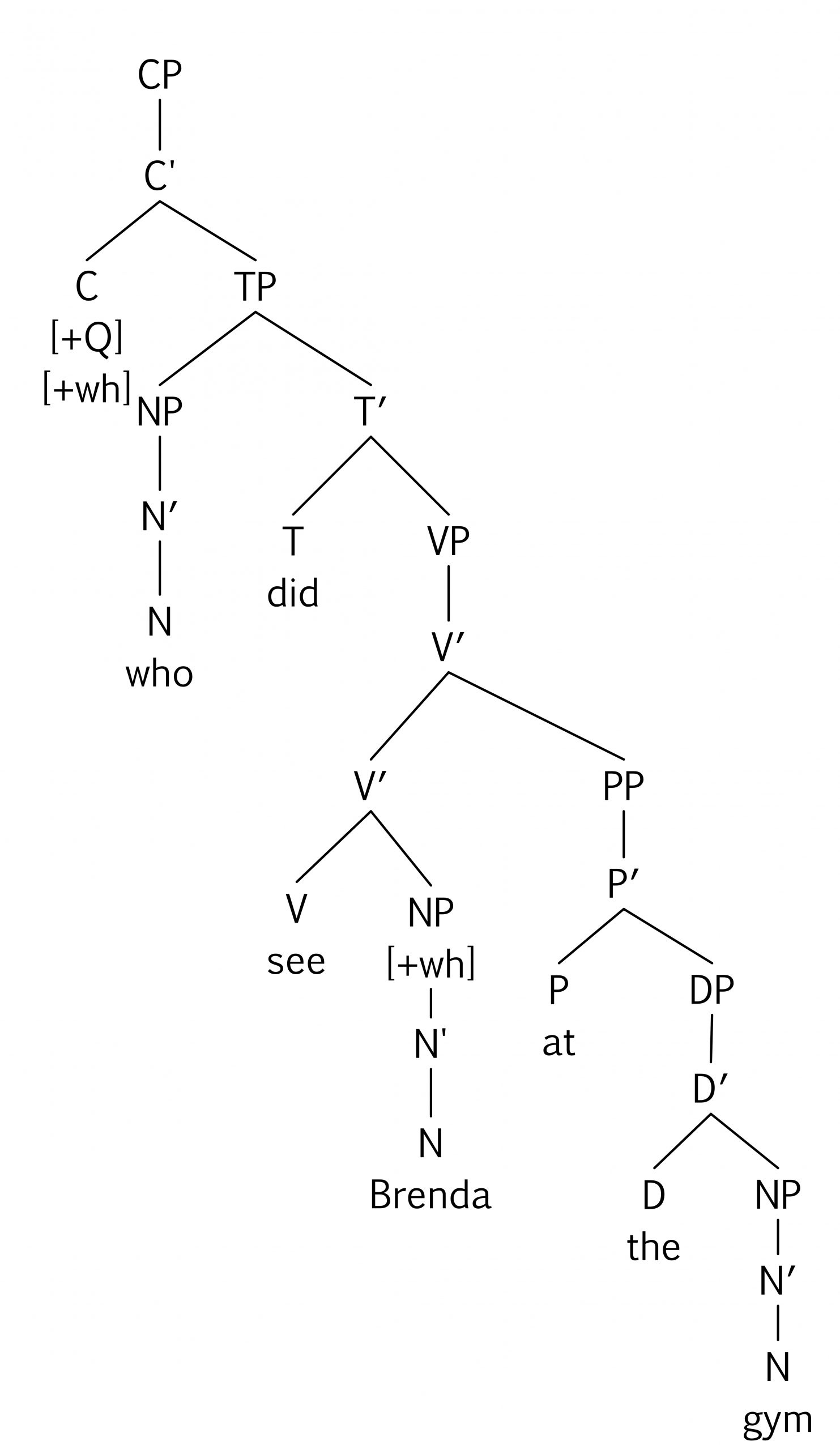

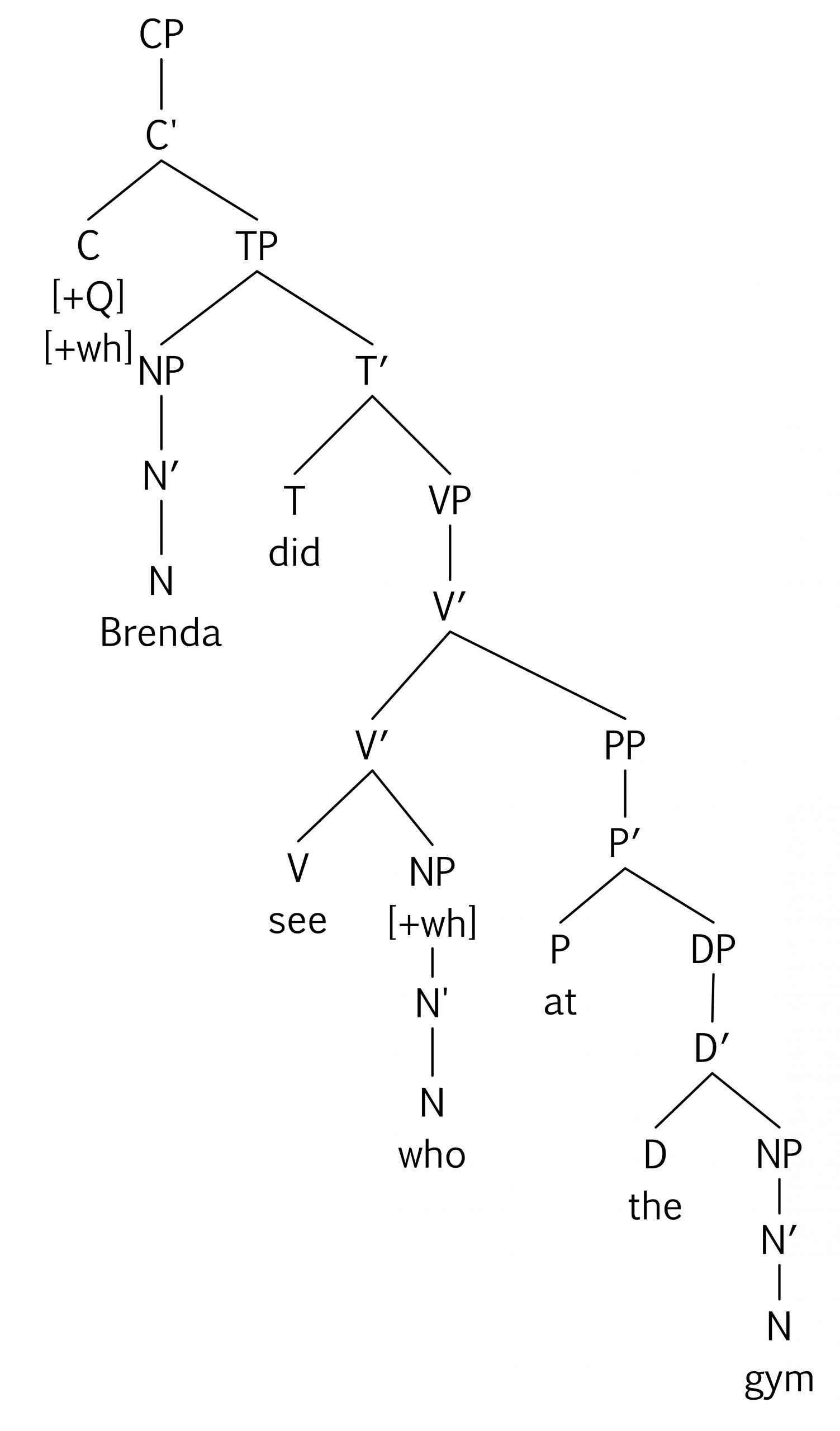

1. Which tree diagram correctly represents the Deep Structure for the question, “Who did Brenda see at the gym?”

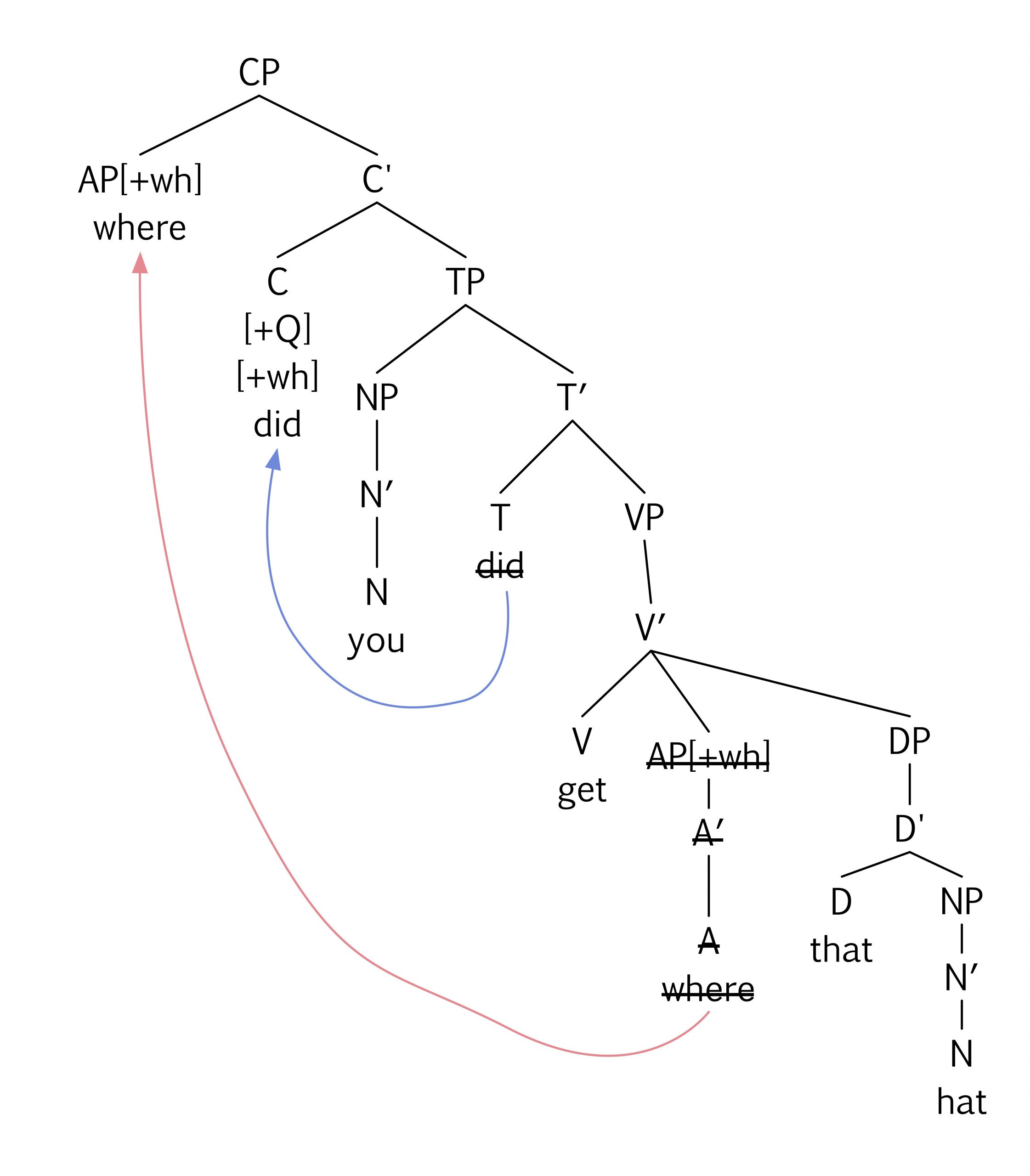

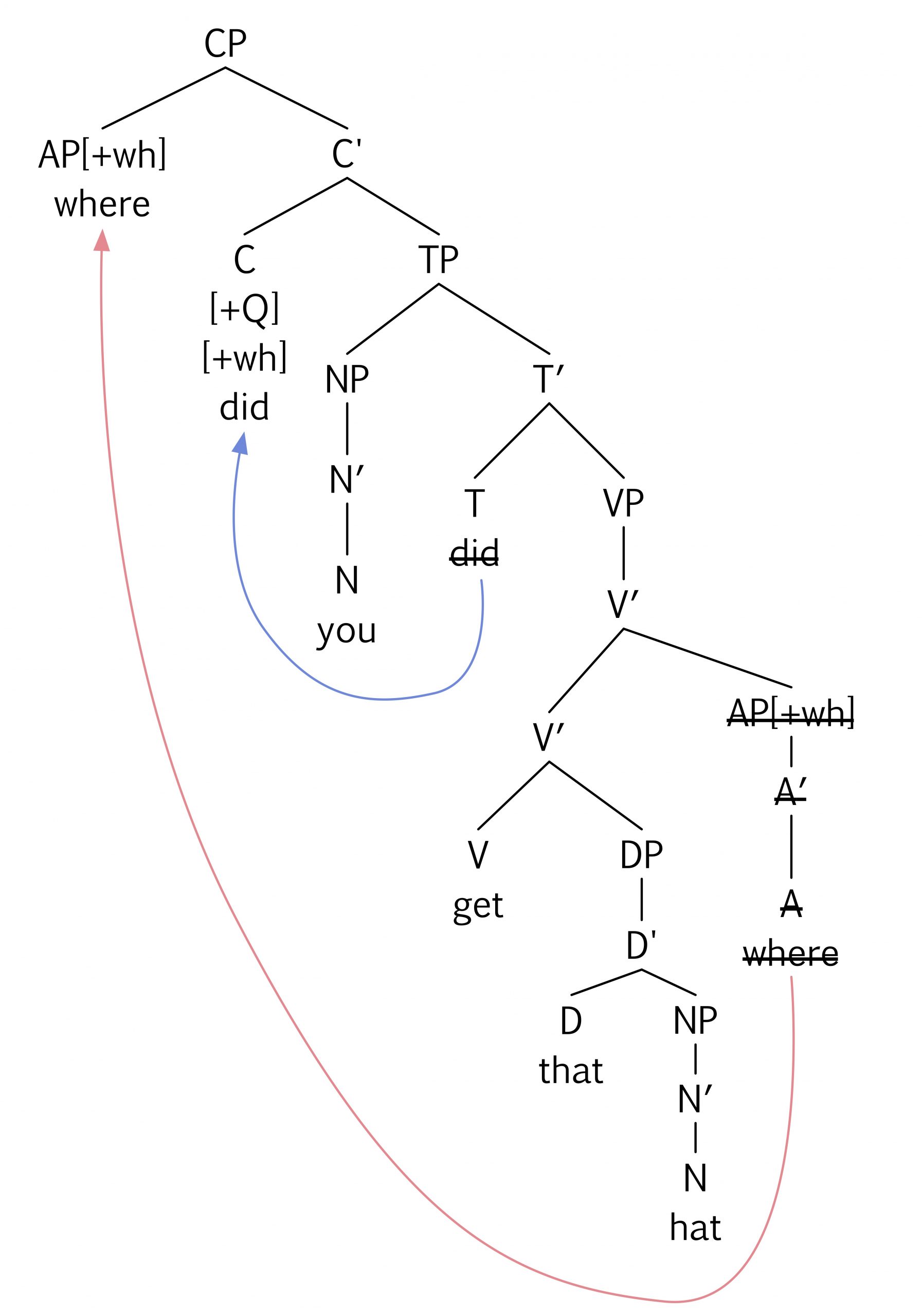

2. Which tree diagram correctly represents the Surface Structure for the question, “Where did you get that hat?”

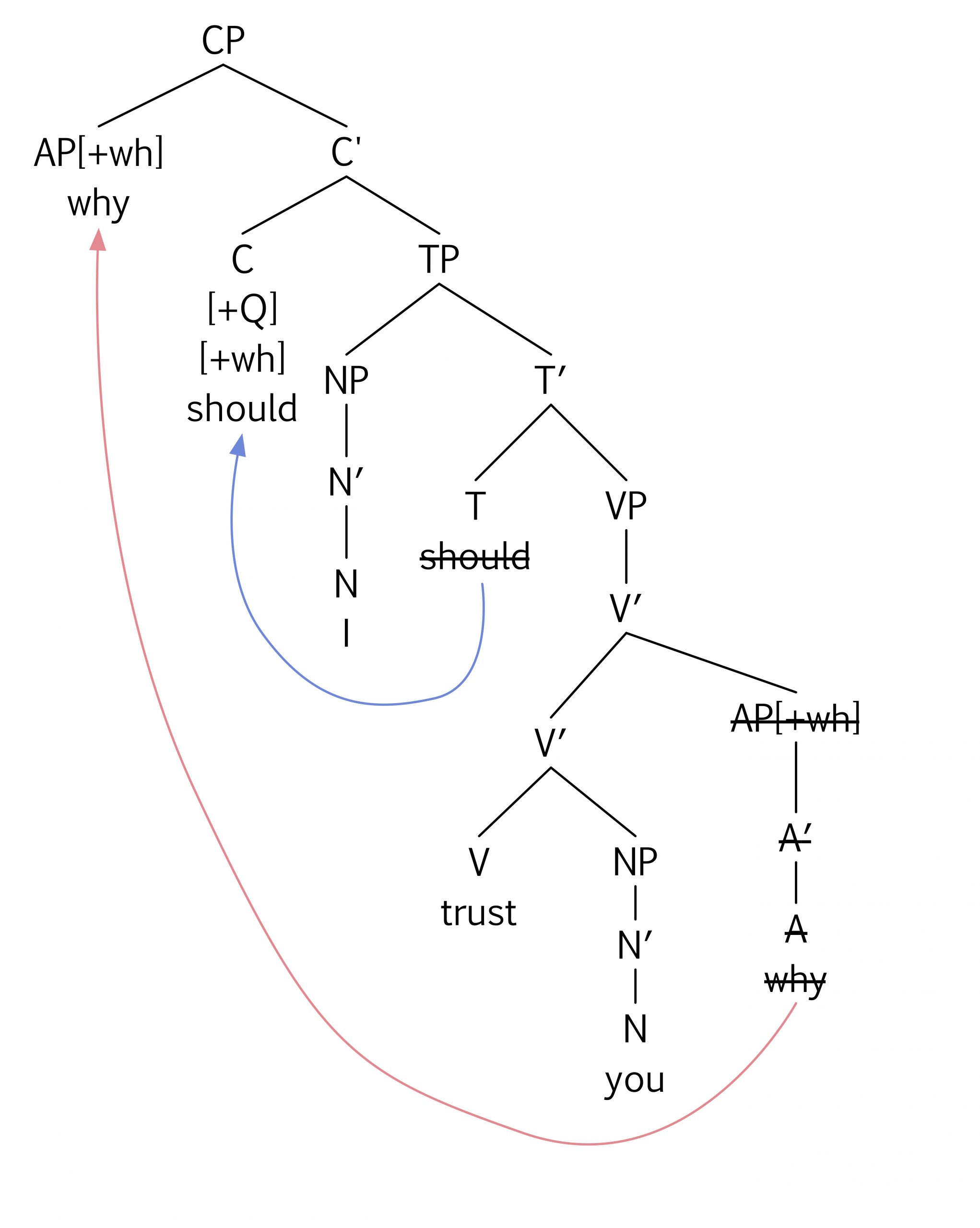

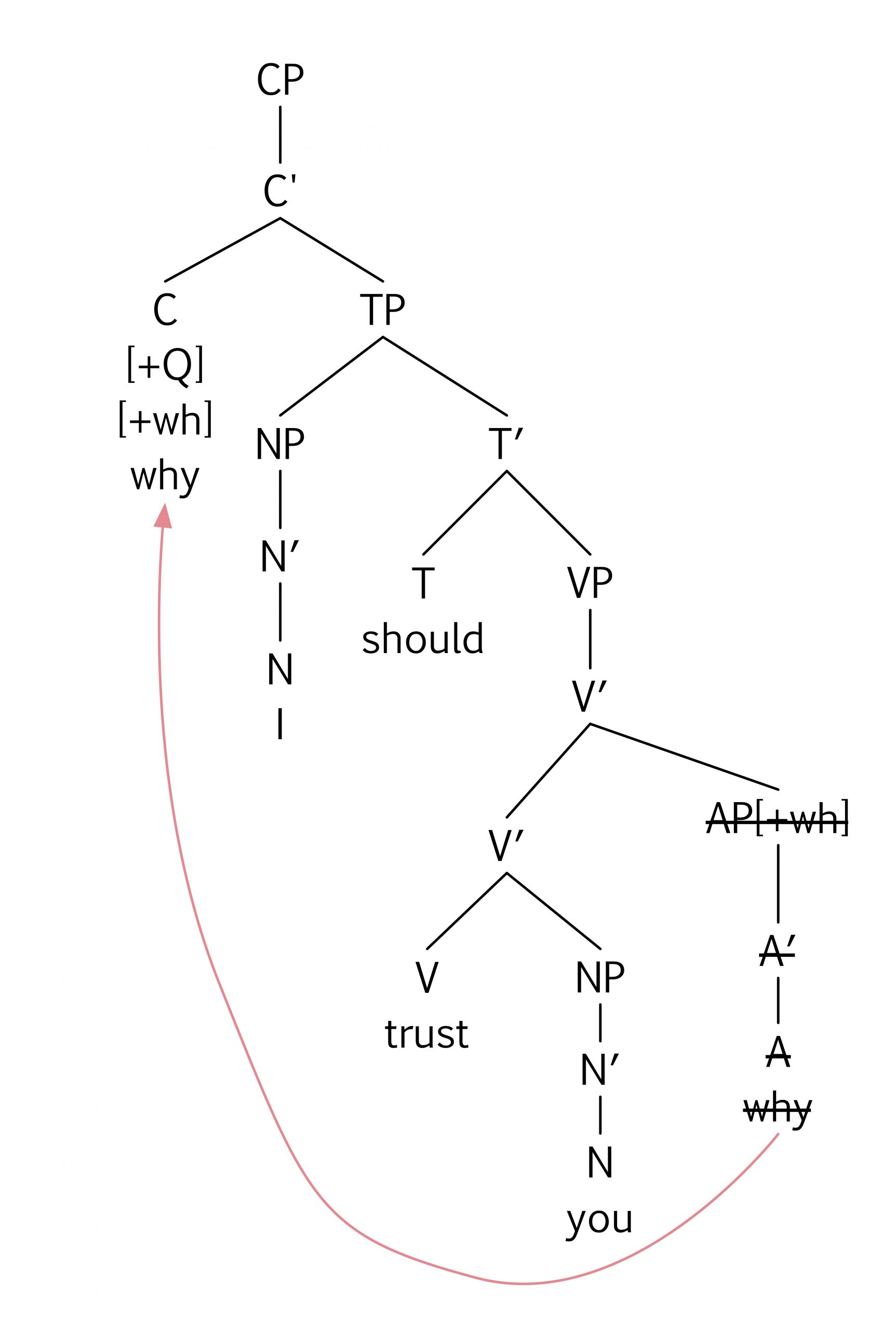

3. Which tree diagram correctly represents the Surface Structure for the question, “Why should I trust you?”

Video Script

In the last unit, we extended our model of the syntax component of the mental grammar. The idea is that we draw words, morphemes and features from our mental lexicon, and the operation MERGE combines them using X-bar principles. The structure that MERGE generates is called a Deep Structure; it’s the underlying form of a sentence that we hold in our minds, but it’s not always exactly like the form that we speak out loud. For some sentences, a second operation, MOVE, takes some elements from the Deep Structure and moves them to another position in the Surface Structure.

The MOVE operation that we’ve seen so far takes a head and moves it to another head position, leaving a trace behind. For obvious reasons, this kind of movement operation is called head movement, and the primary job that head movement does is to form yes-no questions. For this question, Has Faiza eaten lunch yet?, there’s only a small set of possible answers that are grammatical: yes, no, I don’t know, maybe.

But of course, yes-no questions aren’t the only kinds of questions we ask in English. Take a look at these questions:

What is Ramesh cooking?

Who is he cooking for?

When is Leela arriving?

Where did he buy the ingredients?

Why is he making samosas?

How do they taste?

These questions don’t take Yes or No as their answers, they take phrases.

What is Ramesh cooking? Samosas.

Who is he cooking for? Leela.

When is Leela arriving? In an hour.

Where did he buy the ingredients? At the store.

Why is he making samosas? Because Leela loves them.

How do they taste? Delicious!

We call these wh-questions because most of the English words that we use in these questions are spelled with “wh”. Notice that how counts as a wh-word even though it doesn’t have the letter “w” in it.

What we’re observing here is the Surface Structures of these wh-questions. What might their Deep Structures be? To figure that out, let’s think about what the corresponding declarative sentence would be: imagine the situation where we’re answering each question with a full sentence.

Ramesh is cooking samosas.

He is cooking for Leela.

He bought the ingredients at the store.

Our theory claims that in the Deep Structure of a wh-question, the wh-phrase is generated in the position that it would occupy if it were the answer to the question. In other words, the Deep Structure of the sentence, What is Ramesh cooking is really, Ramesh is cooking what. That wh-word what is a pronoun that stands in for the Noun Phrase that refers to what he really is cooking. In the situation where we’re asking this question, we don’t know that the answer to the question is samosas, so we need a question word that lets us refer to the samosas without knowing their identity. The wh-word what does that job and the idea is that the structural relationship between the verb cooking and the pronoun what is the same as the structural relationship between cooking and samosas.

Let’s see how it looks in a tree diagram. Here’s the declarative sentence, Ramesh is cooking samosas. The samosas are the direct object: they’re the NP in the complement of the verb cooking. And in this declarative sentence, the Surface Structure and the Deep Structure are the same. But if we didn’t know what Ramesh was cooking, and we wanted to ask the question, MERGE generates a slightly different Deep Structure, like this.

Notice that the C-head contains a [+Q] feature because we’re going to be asking a question, and a [+wh] feature because the question is going to be a wh-question. Also notice that this wh-phrase, what, has a wh-feature on it too.

So do we form the surface structure by moving what up into the C-head position? There are two reasons that’s not going to work. The first is obvious: we know, from observing our own grammaticality judgments, that, What Ramesh is cooking is not the surface form of our sentence! And the second reason is for the sake of the theory: C is a head position, so it would mess up the consistency of our theory if we allowed a phrase to move into a head position. Besides, we’re going to need that C head position for something else very soon.

The landing site for wh-movement is a position we haven’t yet used, it’s the specifier of CP, sister to C-bar and daughter to CP. The idea is that moving a wh-phrase into the specifier of CP supports the wh-feature in C.

Now, of course, this still isn’t the right Surface Structure for this sentence. What still needs to happen? We still have this [+Q] feature in C-head that needs to get supported as well, so in this wh-question, in addition to the wh-movement of the wh-phrase up to the Specifier of CP, we also have head-movement of the auxiliary from V to T to C. And that leads to the grammatical Surface Structure, what is Ramesh cooking?

So we’ve now seen two different ways that the MOVE operation works. For head movement, it’s a head that moves, and it moves to another head position. For wh-movement, it’s a whole phrase that moves, and it ends up in the Specifier of CP. So when you’re depicting movement, always check that you’ve got the right kind of node moving to the right position.

Now it’s time for you to practice. Look back at these other wh-questions we generated. These are the Surface Structures of these questions. Try drawing trees to represent the Deep Structures of these sentences, and then draw the movement operations that generate the Surface Structure.