1 Introduction to the Public Speaking Context

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three components of getting your message across to others.

- Describe elements in the transactional model of communication.

Communication is a Process

Communication is a process, not a singular event. A basic definition of communication is “sharing meaning between two or more people.” By definition of a process, we must take a series of actions or steps in order to reach a defined end goal. When we follow this process, we carefully consider how to best present information to reach our goals in a given context. When we do not follow the process, we leave our speaking success up to chance.

How do you get your message heard?

We live in a world with a lot of noise. Getting your message heard above others depends on three fundamental components: message, skill, and passion.

Message: When what you are saying is clear and coherent, people are more likely to pay attention to it. On the other hand, when a message is ambiguous, people will often stop paying attention. Working through the speechmaking process in the next chapter will help us to create clear and coherent messages.

Effective communication skills: You may have the best ideas in the world, but if you do not possess the skills to communicate those ideas effectively, you’re going to have a problem getting anyone to listen. In this book, we will address the skills you must possess to effectively communicate your ideas to others.

Passion: One mistake that novice public speakers make is picking topics in which they have no emotional investment. If you are not interested in your message, you cannot expect others to be. Passion is the extra spark that draws people’s attention and makes them want to listen to your message. Your audience can tell if you don’t really care about your topic, and they will just tune you out. We will explore how to choose topics in the next chapter.

Public Speaking Elements

Most who study the speech communication process agree that there are several critical components present in nearly every speech. Understanding these elements can provide us with information that will help us to navigate any speaking context successfully.

Message: Messages are the content of what you are communicating. They may be informal and spontaneous, such as small talk, or formal, intentional, and planned, such as a commencement address. In public speaking, we focus on the creation of formal and deliberate messages.

Noise: Noise refers to anything that interferes with message transmission or reception (i.e., getting the image from your head into others’ heads). There are four types of noise.

- Physiological noise: Physiological processes and states that interfere with a message. For instance, if a speaker has a headache or the flu, or if audience members are hot or they’re hungry, these conditions may interfere with message accuracy.

- Psychological noise: This refers to the mental states or emotional states that impede message transmission or reception. For example, audience members may be thinking about what they want to eat for lunch, or about a date they had last night. Or a speaker may be anxious about the speech.

- Physical noise: This is the actual sound level in a room. There may be noise from the air conditioner or the projector. Or maybe the person next to you clicking their pen.

- Cultural: Message interference that results from differences in people’s worldviews is cultural noise. The greater the difference in worldview, the more difficult it is to understand one another and communicate effectively.

Feedback: This is the message sent from the receiver back to the sender. Feedback in public speaking is usually nonverbal, such as head movement, facial expressions, laughter, eye contact, posture, and other behaviors that we use to judge audience involvement, understanding, and approval. These types of feedback can be positive (nodding, sitting up, leaning forward, smiling) or less than positive (tapping fingers, fidgeting, lack of eye contact, checking devices). There are times when verbal feedback from the audience is appropriate. You may stop and entertain questions about your content, or the audience may fill out a comment card at the end of the speech.

Outcome: The outcome is the result of the public speaking situation. For example, if you ask an audience to consider becoming bone marrow donors, there are certain outcomes. They will either have more information about the subject and feel more informed; they will disagree with you; they will take in the information but do nothing about the topic; and/or they will decide it’s a good idea to become a donor and go through the steps to do so. If they become potential donors, they will add to the pool of existing donors and perhaps save a life. Thus, either they have changed or the social context has changed, or both.

The Transactional Model of Public Speaking

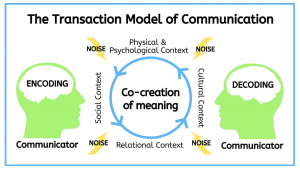

The transactional model of communication illustrates the elements in public speaking visually so we can understand how meaning is co-crated. Transactional communication means that there is a continuous and simultaneous exchange of information between people. The process of encoding and decoding is an important consideration because it takes into account misunderstandings. How often have you had a message that you thought you shared effectively only for the receiving party to completely misinterpret your meaning? Although interpreting a speaker’s message may sound easy in theory, in practice many problems can arise. A speaker’s verbal message, nonverbal communication, and mediated presentation aids can make a message either clearer or harder to understand. For example, unfamiliar vocabulary, speaking too fast or too softly, or small print on presentation aids may make it difficult for you to figure out what the speaker means. Conversely, by providing definitions of complex terms, using well-timed gestures, or displaying graphs of quantitative information, the speaker can help you interpret his or her meaning. Once you have interpreted what the speaker is communicating, you then evaluate the message. Was it good? Do you agree or disagree with the speaker? Is a speaker’s argument logical? These are all questions that you may ask yourself when listening to a speech.

The idea that meanings are cocreated between people is based on a concept called the “field of experience.” According to West and Turner, a field of experience involves “how a person’s culture, experiences, and heredity influence his or her ability to communicate with another” (West & Turner, 2010). Our education, race, gender, ethnicity, religion, personality, beliefs, actions, attitudes, languages, social status, past experiences, and customs are all aspects of our field of experience, which we bring to every interaction. For meaning to occur, we must have some shared experiences with our audience; this makes it challenging to speak effectively to audiences with very different experiences from our own. Our goal as public speakers is to build upon shared fields of experience so that we can help audience members interpret our message.

Key Takeaways

- Getting your message across to others effectively requires attention to message content, skill in communicating content, and your passion for the information presented.

- The interactional models of communication provide a useful foundation for understanding communication and outline basic concepts such as sender, receiver, context noise, message, channel, feedback, and outcomes.

- Examining each public speaking situation using the elements of public speaking will help us to create more effective messages for our audience.

References

Arnett, R. C., & Arneson, P. (1999). Dialogic civility in a cynical age: Community, hope, and interpersonal relationships. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Bakhtin, M. (2001a). The problem of speech genres. (V. W. McGee, Trans., 1986). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1227–1245). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953.).

Bakhtin, M. (2001b). Marxism and the philosophy of language. (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans., 1973). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1210–1226). Boston, MA: Medford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953).

Barnlund, D. C. (2008). A transactional model of communication. In C. D. Mortensen (Ed.), Communication theory (2nd ed., pp. 47–57). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

DeVito, J. A. (2009). The interpersonal communication book (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Geissner, H., & Slembek, E. (1986). Miteinander sprechen und handeln [Speak and act: Living and working together]. Frankfurt, Germany: Scriptor.

Mortenson, C. D. (1972). Communication: The study of human communication. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of communication (pp. 3–26). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Understanding the Process of Public Speaking. (2021, February 20). https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@go/page/17728

West, R., & Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, p. 13.

Wrench, J. S., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2008). Human communication in everyday life: Explanations and applications. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 17.

Yakubinsky, L. P. (1997). On dialogic speech. (M. Eskin, Trans.). PMLA, 112(2), 249–256. (Original work published in 1923).