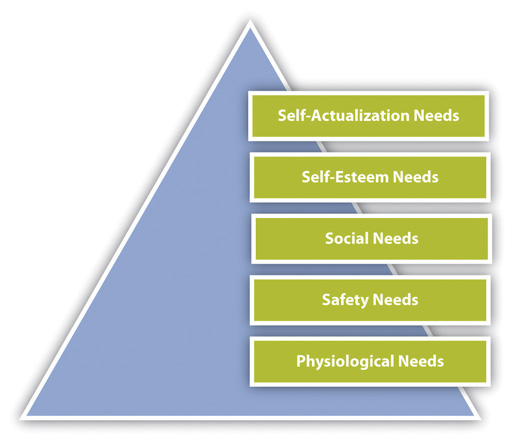

45 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Learning Objectives

- Identify the multiple levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as it relates to public speaking

- Distinguish between the needs and their connection to the audience

Physiological needs form the base of the hierarchy of needs. The closer the needs are to the base, the more important they are for human survival. Speakers do not appeal to physiological needs. After all, a person who doesn’t have food, air, or water isn’t very likely to want to engage in persuasion, and it wouldn’t be ethical to deny or promise these things to someone for persuasive gain. Some speakers attempt to appeal to self-actualization needs, but I argue that this is difficult to do ethically. Self-actualization refers to our need to achieve our highest potential, and these needs are much more intrapersonal than the others. We achieve our highest potential through things that are individual to us, and these are often things that we protect from outsiders. Some examples include pursuing higher education and intellectual fulfillment, pursuing art or music, or pursuing religious or spiritual fulfillment. These are often things we do by ourselves and for ourselves, so I like to think of this as sacred ground that should be left alone. Speakers are more likely to be successful at focusing on safety, social, and self-esteem needs.

We satisfy our safety needs when we work to preserve our safety and the safety of our loved ones. Speakers can combine appeals to safety with positive motivation by presenting information that will result in increased safety and security. Combining safety needs and negative motivation, a speaker may convey that audience members’ safety and security will be put at risk if the speaker’s message isn’t followed. Combining negative motivation and safety needs depends on using some degree of fear as a motivator. Think of how the insurance industry relies on appeals to safety needs for their business. While this is not necessarily a bad strategy, it can be done more or less ethically.

Ethics of Using Fear Appeals

- Do not overuse fear appeals.

- The threat must be credible and supported by evidence.

- Empower the audience to address the threat.

I saw a perfect example of a persuasive appeal to safety while waiting at the shop for my car to be fixed. A pamphlet cover with a yellow and black message reading, “Warning,” and a stark black and white picture of a little boy picking up a ball with the back fender of a car a few feet from his head beckoned to me from across the room. The brochure was produced by an organization called Kids and Cars, whose tagline is “Love them, protect them.” While the cover of the brochure was designed to provoke the receiver and compel them to open the brochure, the information inside met the ethical guidelines for using fear appeals. The first statistic noted that at least two children a week are killed when they are backed over in a driveway or parking lot. The statistic is followed by safety tips to empower the audience to address the threat. You can see a video example of how this organization effectively uses fear appeals in Video 11.1.

Video Clip 11.1

Kids and Cars: Bye-Bye Syndrome

This video illustrates how a fear appeal aimed at safety needs can be persuasive. The goal is to get the attention of audience members and compel them to check out the information the organization provides. Since the information provided by the organization supports the credibility of the threat, empowers the audience to address the threat, and is free, this is an example of an ethical fear appeal.

Our social needs relate to our desire to belong to supportive and caring groups. We meet social needs through interpersonal relationships ranging from acquaintances to intimate partnerships. We also become part of interest groups or social or political groups that help create our sense of identity. The existence and power of peer pressure is a testament to the motivating power of social needs. People go to great lengths and sometimes make poor decisions they later regret to be a part of the “in-group.” Advertisers often rely on creating a sense of exclusivity to appeal to people’s social needs. Positive and negative motivation can be combined with social appeals. Positive motivation is present in messages that promise the receiver “in-group” status or belonging, and negative motivation can be seen in messages that persuade by saying, “Don’t be left out.” Although these arguments may rely on the bandwagon fallacy to varying degrees, they draw out insecurities people have about being in the “out-group.”

We all have a need to think well of ourselves and have others think well of us, which ties to our self-esteem needs. Messages that combine appeals to self-esteem needs and positive motivation often promise increases in respect and status. A financial planner may persuade by inviting a receiver to imagine prosperity that will result from accepting his or her message. A publicly supported radio station may persuade listeners to donate money to the station by highlighting a potential contribution to society. The health and beauty industries may persuade consumers to buy their products by promising increased attractiveness. While it may seem shallow to entertain such ego needs, they are an important part of our psychological makeup. Unfortunately, some sources of persuasive messages are more concerned with their own gain than the well-being of others and may take advantage of people’s insecurities in order to advance their persuasive message. Instead, ethical speakers should use appeals to self-esteem that focus on prosperity, contribution, and attractiveness in ways that empower listeners.

Key Takeaways

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs can provide valuable information about audience needs.

- We must appeal to audience’s needs to be successful with persuasion.

References

Cooper, M. D., and William L. Nothstine, Power Persuasion: Moving an Ancient Art into the Media Age (Greenwood, IN: Educational Video Group, 1996), 48.

Fletcher, L., How to Design and Deliver Speeches, 7th ed. (New York: Longman, 2001), 342.

Maslow, A. H., “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Psychological Review 50 (1943): 370–96.

Stiff, J. B., and Paul A. Mongeau, Persuasive Communication, 2nd ed. (New York: Guilford Press, 2003), 105.