Chapter 7: Adolescence

Objectives:

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to…

- Define Adolescence

- Describe major features of physical, cognitive and social development during adolescence

- Understand why adolescence is a period of heightened risk-taking

- Be able to explain sources of diversity in adolescent development

- Summarize the overall physical growth

- Describe the changes that occur during puberty

- Describe the changes in brain maturation

- Compare adolescent formal operational thinking to childhood concrete operational (Piaget’s theory)

- Describe the changes in sleep

- Contrast theories of identity development in adolescence

- Compare aggression and anxiety in adolescence

- Describe eating disorders

- Explain the prevalence, risk factors and consequences of adolescent pregnancy

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Introduction

Adolescence is a period that begins with puberty and ends with the transition to emerging adulthood. For the purposes of this text and this chapter, we will define adolescence as the ages 12 to 18. This chapter will outline changes that occur during adolescence in three domains: physical, cognitive, and social. Within the social domain, changes in relationships with parents, peers, and romantic partners will be considered. Next, the chapter turns to adolescents’ psychological and behavioral adjustment, including identity formation, aggression and antisocial behavior, anxiety, and depression, and academic achievement. Finally, the chapter summarizes sources of diversity in adolescents’ experiences and development.

Adolescence Defined (Ob 1)

Adolescence is often characterized as a period of transformation, primarily, in terms of physical, cognitive, and social-relational change. Adolescence is a developmental stage that has been defined as starting with puberty and ending with the transition to adulthood (approximately ages 10–20). Adolescence has evolved historically, with evidence indicating that this stage is lengthening as individuals start puberty earlier and transition to adulthood later than in the past.

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). For both boys and girls, these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls.

Puberty today begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for girls and 11–12 years for boys. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by heredity; however environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence.

The average age of onset for puberty has decreased gradually over time since the 19th century by 3–4 months per decade, which has been attributed to a range of factors including better nutrition, obesity, increased father absence, and other environmental factors (Steinberg, 2013). Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past. In fact, the prolonging of adolescence has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood, occurring from approximately ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000).

Growth in Adolescence (Ob 4)

Puberty is a period of rapid growth and sexual maturation. These changes begin sometime between 8 and 14. It typically begins between the ages of eight and thirteen years in females, and between nine and fourteen years in males (NIH, 2024). Its onset is influenced by many factors, both biological and environmental.

Puberty occurs over two distinct phases, and the first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes—such as skeletal growth. The second phase of puberty, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation. Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably a major rush of estrogen for girls and testosterone for boys. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioral and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state; the process is triggered by the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the blood stream and initiates a chain reaction.

Physical Growth Spurt (Ob 2, 4)

Adolescents experience an overall physical growth spurt. The growth proceeds from the extremities toward the torso. This is referred to as distal proximal development. First the hands grow, then the arms, and finally the torso. The overall physical growth spurt results in 10-11 inches of added height and 50 to 75 pounds of increased weight. The head begins to grow sometime after the feet have gone through their period of growth. Growth of the head is preceded by growth of the ears, nose, and lips. The difference in these patterns of growth result in adolescents appearing awkward and out-of-proportion. As the torso grows, so does the internal organs. The heart and lungs experience dramatic growth during this period.

During childhood, boys and girls are quite similar in height and weight. However, biological sex differences become apparent during adolescence. From approximately age 10 to 14, the average girl is taller but not heavier than the average boy. For girls the growth spurt begins between 8 and 13 years old (average 10-11), with adult height reached between 10 and 16 years old. After that, the average boy becomes both taller and heavier, although individual differences are certainly noted. Boys begin their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old (average 12-13), and reach their adult height between 13 and 17 years old. As adolescents physically mature, weight differences are more noteworthy than height differences. At eighteen years of age, those that are heaviest weigh almost twice as much as the lightest, but the tallest teens are only about 10% taller than the shortest (Seifert, 2012). Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence both height and weight.

Both height and weight can certainly be sensitive issues for some teenagers. Most modern societies and the teenagers in them tend to favor relatively short women and tall men, as well as a somewhat thin body build, especially for girls and women. Yet, neither socially preferred height nor thinness is the destiny for many individuals. Being overweight, in particular, has become a common, serious problem in modern society due to the prevalence of diets high in fat and lifestyles low in activity (Tartamella et al., 2004). The educational system has, unfortunately, contributed to the problem as well by gradually restricting the number of physical education courses and classes in the past two decades.

Average height and weight are also related somewhat to racial and ethnic background. In general, children of Asian background tend to be slightly shorter than children of European and North American background. The latter in turn tend to be shorter than children from African societies (Eveleth & Tanner, 1990). Body shape differs slightly as well, though the differences are not always visible until after puberty. Asian background youth tend to have arms and legs that are a bit short relative to their torsos, and African background youth tend to have relatively long arms and legs. The differences are only averages as there are large individual differences as well.

Sexual Development (Ob 4, Ob 6)

Typically, the growth spurt is followed by the development of sexual maturity. Sexual changes are divided into two categories: Primary sexual characteristics and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary sexual characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age. Males produce their sperm on a cycle, and unlike the female’s ovulation cycle, the male sperm production cycle is constantly producing millions of sperm daily. The main male sex organs are the penis and the testicles, the latter of which produce semen and sperm. For females, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth but are immature. Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs (Crooks & Baur, 2007). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and a higher percentage of body fat can bring menstruation at younger ages.

Secondary sexual characteristics are visible physical changes not directly linked to reproduction, but signal sexual maturity. For males, this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms, and on the face. For female’s breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser.

Acne: An unpleasant consequence of the hormonal changes in puberty is acne, defined as pimples on the skin due to overactive sebaceous (oil-producing) glands (Dolgin, 2011). These glands develop at a greater speed than the skin ducts that discharges the oil. Consequently, the ducts can become blocked with dead skin and acne will develop. According to the University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center (2000), approximately 85% of adolescents develop acne and boys develop acne more than girls because of greater levels of testosterone in their systems (Dolgin, 2011). Experiencing acne can lead the adolescent to withdraw socially, especially if they are self-conscious about their skin or teased (Goodman, 2006).

The onset of puberty is driven by complex biological processes, including genetic factors, hormonal changes, and the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary (HPA) axis. The hypothalamus signals the pituitary gland to release gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which triggers the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). These hormones stimulate the testes in males and ovaries in females, initiating the physical and sexual maturation associated with puberty (MedlinePlus, 2016; NCBI, 2023). This process transforms the body to become capable of reproduction and is influenced by factors such as nutrition, environmental conditions, and genetics (Nature, 2014; Cleveland Clinic, 2025).

The timing of puberty has a strong genetic component (Hoyt et al., 2020). The age at which an individual’s biological parents went through puberty is a strong determinant in the timing of puberty for their adolescent offspring (Wohlfahrt-Veje et al., 2016). Although timing of parents’ puberty is the strongest predictor of puberty, sociocultural factors also play a role. Factors such as early activation of the HPA, family history, genetic variations, and dealing with additional stressors are known predictive factors for early onset of puberty in females and males (Farello et al., 2019; Gaydosh et al., 2018). Additionally, in females, a certain amount of body fat is necessary for the onset of puberty. The hormone leptin is also thought to play a role in triggering puberty (Ahmed et al., 1999; Blum et al., 1997; Evans et al., 2022), and it is released into the bloodstream by adipose tissue (fat stores). In females, individual and environmental factors in pubertal timing include nutrition, body weight, household composition, exercise, environmental chemicals, and overall levels of stress.

Learn more

Watch this overview of what adolescence means and the role of puberty during this time. This helpful recap highlights the biological basis of puberty and discusses some of the social factors teens experience.

Effects of Pubertal Age

The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout the world. According to Euling et al. (2008) data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in girls. A century ago the average age of a girl’s first period in the United States and Europe was 16, while today it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for boys, it is harder to determine if boys are maturing earlier too. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for girls include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with Asian-American girls, on average, developing last, while African American girls enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic girls start puberty the second earliest, while European-American girls rank third in their age of starting puberty. Although African American girls are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American girls (Weir, 2016). Research has demonstrated mental health problems linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For girls early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). Early maturing girls demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers (Weir, 2016). Problems with early puberty seem to be due to the mismatch between the child’s appearance and the way she acts and thinks. Adults especially may assume the child is more capable than she actually is, and parents might grant more freedom than the child’s age would indicate. For girls, the emphasis on physical attractiveness and sexuality is emphasized at puberty and they may lack effective coping strategies to deal with the attention they may receive.

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when the child is among the first in his or her peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For girls, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior (Weir, 2016). Boys also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle et al. (2010), while most boys experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, boys who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo, or a fast rate of change, actually increased in depressive symptoms. The effects of pubertal tempo were stronger than those of pubertal timing, suggesting that rapid pubertal change in boys may be a more important risk factor than the timing of development. In a further study to better analyze the reasons for this change, Mendle et al. (2012) found that both early maturing boys and rapidly maturing boys displayed decrements in the quality of their peer relationships as they moved into early adolescence, whereas boys with more typical timing and tempo development actually experienced improvements in peer relationships. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships might be especially challenging for boys whose pattern of pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for boys attaining early puberty was increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or other drug use (Dudovitz et al., 2015).

Cognitive Development (Ob 2)

Adolescent Brain (Ob 3, Ob 7)

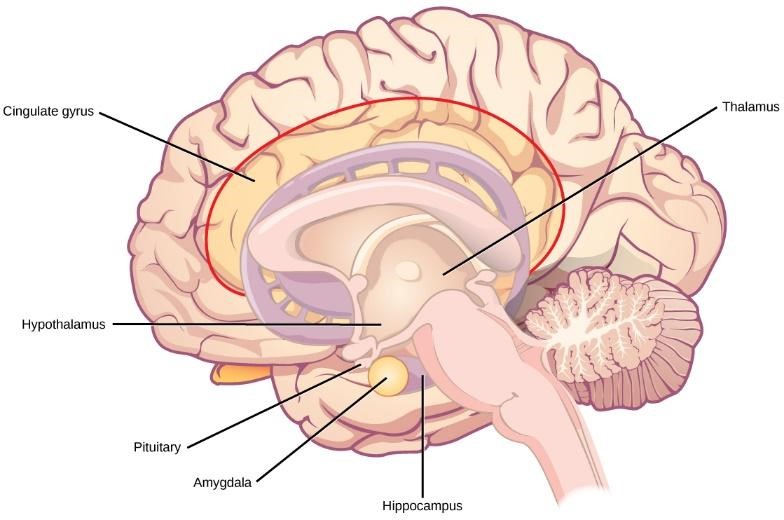

Adolescence is a critical period of brain development, driven by hormonal changes and marked by significant neurological growth that continues into the mid-20s. Although the brain reaches 90% of its adult size by age six or seven and its full size during adolescence, its maturation involves complex structural and functional changes rather than further growth in size. Key developments occur in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like decision-making and impulse control, and the limbic system, which governs emotions, memory, and sensory processing. Processes such as synaptic pruning and myelination enhance neural efficiency, while the creases in the brain’s cortex become more intricate, particularly in areas handling cognitive and emotional information. However, this growth is uneven, with the emotional limbic system maturing earlier than the rational prefrontal cortex, contributing to typical adolescent behaviors like risk-taking and heightened emotional responses. Additionally, changes in neurotransmitter levels—such as increased dopamine, which enhances reward sensitivity, and fluctuating serotonin, which affects mood regulation—further shape adolescents’ emotional reactivity and stress responses. Together, these changes establish the foundation for adult cognitive and emotional capabilities but also create vulnerabilities to stress, trauma, or substance abuse during this sensitive developmental window. In the next section, we will learn more about changes in the brain connected to changes in the brain and why teenagers engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and have emotional outbursts in the next section.

The brain undergoes dramatic changes during adolescence. Although it does not get larger, it matures by becoming more interconnected and specialized (Giedd, 2015). The adolescent brain undergoes significant structural and functional changes, becoming more interconnected and specialized without increasing in size (Giedd, 2015). Myelination and synaptic pruning strengthen neural connections, increasing white matter and efficiency while reducing cortical gray matter (Dobbs, 2012). Language areas myelinate early, consolidating skills but reducing plasticity for learning new languages. Key developments include the thickening of the corpus callosum, stronger hippocampal-prefrontal connections for integrating memory into decision-making, and maturation of the prefrontal cortex, responsible for impulse control and planning, which continues into the mid-20s (Hartley & Somerville, 2015; Casey et al., 2005).

Major changes in the structure and functioning of the brain occur during adolescence and result in cognitive and behavioral developments (Steinberg, 2008). Cognitive changes during adolescence include a shift from concrete to more abstract and complex thinking. Such changes are fostered by improvements during early adolescence in attention, memory, processing speed, and metacognition (ability to think about thinking and therefore make better use of strategies like mnemonic devices that can improve thinking). As explained before, early in adolescence, changes in the brain’s limbic system contribute to increases in adolescents’ sensation-seeking and reward motivation. Later in adolescence, the brain’s cognitive control centers in the prefrontal cortex develop, increasing adolescents’ self-regulation and future orientation.

The prefrontal cortex which is involved in the control of impulses, organization, planning, and making good decisions, does not fully develop until the mid-20s. Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey et al., 2005).

To complicate matters, the limbic system, which important role in determining rewards and punishments and processing emotional experience and social information, develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. The limbic system, linked to emotion, reward, and social interaction, develops earlier and is influenced by puberty-related hormonal changes like dopamine and oxytocin, driving sensation-seeking and peer bonding (Romeo, 2013; Dobbs, 2012). The limbic system is linked to the hormonal changes that occur at puberty. The limbic system is also related to novelty seeking and a shift toward interacting with peers. Pubertal hormones target the amygdala (part of limbic system) directly and powerful sensations become compelling (Romeo, 2013).

The approximately 10 years that separate the development of these two brain areas can result in risky behavior, poor decision-making, and weak emotional control for the adolescent. When puberty begins earlier, this mismatch extends even further. Teens often take more risks than adults and according to research, it is because they weigh risks and rewards differently than adults do (Dobbs, 2012). For adolescents, the brain’s sensitivity to the neurotransmitter dopamine peaks and dopamine is involved in reward circuits so the possible rewards outweigh the risks. Adolescents respond especially strongly to social rewards during activities, and they prefer the company of others their same age. In addition to dopamine, the adolescent brain is affected by oxytocin which facilitates bonding and makes social connections more rewarding. This developmental mismatch between the limbic system and prefrontal cortex contributes to risk-taking and poor emotional regulation during adolescence (Giedd, 2015). Adolescents’ heightened sensitivity to dopamine amplifies their focus on rewards over risks, especially in social contexts.

Additionally, during this period of development, the adolescent brain is especially vulnerable to damage from drug exposure. Consequently, adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of repeated marijuana exposure (Weir, 2015). While this period increases vulnerability to mental illness and substance abuse (50% of mental illnesses emerge by age 14), it also fosters adaptive behaviors like novelty-seeking and independence from family (Weir, 2015; Giedd, 2015). Cognitive advancements include shifts to abstract thinking, improved attention, memory, processing speed, and metacognition (Steinberg, 2008). Novelty seeking and risk-taking can generate positive outcomes including meeting new people and seeking out new situations. Separating from the family and moving into new relationships and different experiences are actually quite adaptive for society. However, the delayed maturation of cognitive control systems means adolescents are prone to impulsive decisions—almost like having powerful engine without brakes.

As puberty progresses, hormonal changes like increased oxytocin levels enhance social bonding and peer interactions. Oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus and fosters trust, cooperation, and prosocial behaviors among adolescents, while the rapid development of brain regions involved in social processing amplifies the importance of peer relationships in decision-making (He et al., 2018; Anderson, 2023). Peer approval becomes as rewarding as tangible incentives like money or food, influencing adolescent behavior and risk-taking. This heightened sensitivity to social rewards helps explain why teens prioritize peer influence in their decisions (Steinberg, 2008). Together, these biological and social changes underscore puberty’s profound impact on both physical maturation and social development.

Learn more

Cognitive neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore examines the differences between the prefrontal cortex of adolescents and that of adults to illustrate how “teenage” behaviors typically stem from the growing and developing brain.

Piaget’s Formal Operational Stage of Cognitive Development (Ob 8)

During the formal operational stage, adolescents are able to understand abstract principles which have no physical reference. They can now contemplate such abstract constructs as beauty, love, freedom, and morality. The adolescent is no longer limited by what can be directly seen or heard. Additionally, while younger children solve problems through trial and error, adolescents demonstrate hypothetical-deductive reasoning, which is developing hypotheses based on what might logically occur. They are able to think about all the possibilities in a situation beforehand, and then test them systematically (Crain, 2005). Now they are able to engage in true scientific thinking. Formal operational thinking also involves accepting hypothetical situations. Adolescents understand the concept of transitivity, which means that a relationship between two elements is carried over to other elements logically related to the first two, such as if A<B and B<C, then A<C (Thomas, 1979). For example, when asked: If Maria is shorter than Alicia and Alicia is shorter than Caitlyn, who is the shortest? Adolescents are able to answer the question correctly as they understand the transitivity involved.

Does everyone reach formal operations? According to Piaget, most people attain some degree of formal operational thinking, but use formal operations primarily in the areas of their strongest interest (Crain, 2005). In fact, most adults do not regularly demonstrate formal operational thought, and in small villages and tribal communities, it is barely used at all. A possible explanation is that an individual’s thinking has not been sufficiently challenged to demonstrate formal operational thought in all areas.

Adolescent Egocentrism: Once adolescents can understand abstract thoughts, they enter a world of hypothetical possibilities and demonstrate egocentrism or a heightened self-focus. David Elkind (1967) expanded on the concept of Piaget’s adolescent egocentricity. Elkind theorized that the physiological changes that occur during adolescence result in adolescents being primarily concerned with themselves. Additionally, since adolescents fail to differentiate between what others are thinking and their own thoughts, they believe that others are just as fascinated with their behavior and appearance. This belief results in the adolescent anticipating the reactions of others, and consequently constructing an imaginary audience. “The imaginary audience is the adolescent’s belief that those around them are as concerned and focused on their appearance as they themselves are” (Schwartz et al., 2008, p. 441). Elkind thought that the imaginary audience contributed to the self-consciousness that occurs during early adolescence.

The desire for privacy and reluctance to share personal information may be a further reaction to feeling under constant observation by others. Another important consequence of adolescent egocentrism is the personal fable or belief that one is unique, special, and invulnerable to harm. Elkind (1967) explains that because adolescents feel so important to others (imaginary audience) they regard themselves and their feelings as being special and unique. Adolescents believe that only they have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invulnerability, especially to death. Adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences. Elkind believed that adolescent egocentricity emerged in early adolescence and declined in middle adolescence, however, recent research has also identified egocentricity in late adolescence (Schwartz, et al., 2008).

Consequences of Formal Operational Thought: Adolescent thought undergoes significant changes as teens develop the ability to think abstractly, consider multiple dimensions of a problem, and adopt relativistic perspectives. Adolescents begin to engage deeply with abstract concepts like justice, equality, and fairness, moving beyond the concrete thinking of childhood (Malti et al., 2020). They can evaluate complex situations from multiple angles, such as recognizing both the rationale and unintended consequences of a school dress code policy. This multidimensional thinking also fosters an appreciation for sarcasm and irony, as well as a tendency to question rules that seem arbitrary (Glenwright et al., 2017). Adolescents’ ability to think about possibilities leads to relativistic thinking, where they understand that truths can depend on perspective. For instance, they may recognize how two friends could both be correct in their answers on a test depending on context and use this insight to seek clarification from a teacher (Chandler et al., 1990).

This cognitive growth allows adolescents to see multiple perspectives simultaneously, but it can also lead to frustration as they realize that many issues lack clear right or wrong answers. The newfound ability to think critically about rules and authority often results in de-idealization of adults who shape their world. Adolescents’ relativistic thinking highlights the complexity of truth and perspective, reinforcing their capacity for nuanced problem-solving and social reasoning. However, this stage of cognitive development also brings challenges as teens navigate the ambiguity of possibilities and perspectives in their expanding intellectual and social worlds.

Information Processing (Ob 2)

The information processing perspective integrates Piagetian principles with modern insights into biological foundations of cognitive domains like processing speed, metacognition, reasoning, and decision-making. Adolescent brain maturation drives rapid growth in these areas, with perceptual speed—the ability to quickly recognize symbols—peaking in late adolescence before declining (Kail & Ferrer, 2007; Schaie, 1994). Enhanced perceptual speed improves job and academic performance through heightened creativity and intelligence (Mount et al., 2008; Rindermann & Neubauer, 2004). Metacognition, the ability to reflect on and regulate one’s thinking, also matures, enabling strategic problem-solving and self-directed learning (Weil et al., 2013; Paulus et al., 2013). Adolescents increasingly assess others’ advice, rejecting misleading input while accepting helpful guidance (Moses-Payne et al., 2021).

Cognitive control: As noted in earlier chapters, executive functions, attention span, increases in working memory, and cognitive flexibility have been steadily improving since early childhood. Studies have found that executive function is very competent in adolescence. Adolescents use cognitive control to balance exploration and planning (Maslowsky et al., 2019; Romer et al., 2017). This strategic approach correlates with better working memory, sensation-seeking, and future-oriented thinking (Maslowsky et al., 2019). However, self-regulation, or the ability to control impulses, may still fail. A failure in self-regulation is especially true when there is high stress or high demand on mental functions (Luciano & Collins, 2012). While high stress or demand may tax even an adult’s self-regulatory abilities, neurological changes in the adolescent brain may make teens particularly prone to more risky decision making under these conditions.

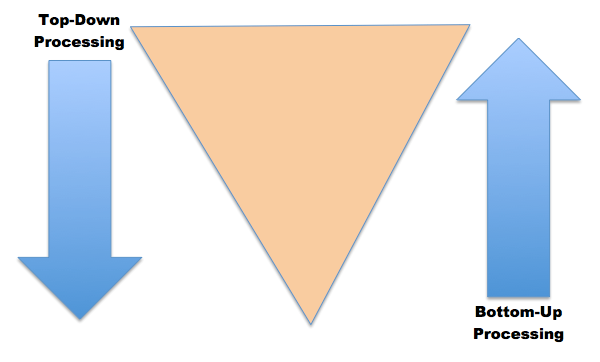

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning: Inductive reasoning emerges in childhood, and is a type of reasoning that is sometimes characterized as “bottom-up processing” in which specific observations, or specific comments from those in authority, may be used to draw general conclusions (e.g., child having two friends who are rude makes a conclusion all friends are rude). However, in inductive reasoning, the veracity of the information that created the general conclusion does not guarantee the accuracy of that conclusion. For instance, a child who has only observed thunder on summer days may conclude that it only thunders in the summer. In contrast, deductive reasoning, sometimes called “top-down-processing,” emerges in adolescence. This type of reasoning starts with some overarching (general) principle and based on this propose specific conclusions. For example, if general theory is all trees are green and then asked what color do you expect a particular tree to be, deduction would say the tree should be green. Or if an adolescent was given the following information: if Jesse is shorter than Matt and Matt is shorter than Tyler, then who is the tallest and the shortest? Deductive reasoning tells us that Tyler is the tallest and Jesse is the shortest. Deductive reasoning guarantees a truthful conclusion if the premises on which it is based are accurate.

Intuitive versus Analytic Thinking: Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the Dual-Process Model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast (Kahneman, 2011), and it is more experiential and emotional. In contrast, analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational. While these systems interact, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier and more commonly used in everyday life. It is also more commonly used by children and teens than by adults (Klaczynski, 2001). The quickness of adolescent thought, along with the maturation of the limbic system, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

Self-regulation: The major developments in the frontal lobe and limbic system during adolescence support the growing ability to exert self-regulation, the ability to manage and control behavior and emotions without outside assistance, including emotional self-regulation (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000; McClelland et al., 2017). This skill allows us to change or inhibit certain thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to achieve better outcomes (Baumeister & Alquist, 2009; Moilanen et al., 2015). Related abilities include task persistence, delayed gratification, self-monitoring, self-reward for progress, management of frustration and distress, and the capacity to seek help when needed (Murray & Rosanbalm, 2017).

Social Changes (Ob 2)

Adolescence is a time many societies set aside for children to transition to adult stature, status, roles, and capabilities. In other countries, children may quickly transition to adult responsibilities without being afforded the time and space to adjust to this immense developmental shift. For instance, in several Asian and African cultures, adolescents tend to have strong family obligations and responsibilities, emphasizing group harmony and family loyalty. Older adolescents in Cambodia and rural Vietnam assume caretaking tasks and the family supporter’s role (Yi, 2015). Teenage girls may face stricter gender roles and fewer opportunities than boys.

To understand the complexities of the adolescent transition, consider the developmental tasks associated with it. These are the biologically, psychologically, and socially relevant challenges of adolescence (Havighurst, 1948; 1972). They include achieving the cognitive development crucial for decision-making, acquiring impulse control and reasoning, developing a sense of self and personal identity, and building friendships while navigating social dynamics to gain a sense of belonging and acceptance. Adolescents also face several psychological and social developmental tasks with some examples shown in the next table.

Table. Some Developmental Tasks of Adolescence (source: McIntosh et al., 2003; OpenStax, 2024)

| Psychological | Social |

|---|---|

|

|

Many societies and cultures use explicit markers to recognize progress toward adult status. Anthropologists call such a marker a rite of passage. Parents, teens, and society alike put much attention and energy into some of these. Notice that no single marker signifies adult status in all areas of life.

Table. Adolescent Rites of Passage Examples

| Marker (Rite) | Age of Adult Status (Years) |

|---|---|

| Participating in bar/bat Mitzvah (Jewish religion) | 12–13 |

| Participating in quinceañera/o (many Latine cultures) | 15 |

| Driving | 15–17 depending on the state |

| Attending “R” rated movie without caregiver | 17 |

| Graduating from high school | 17–19 |

| Voting | 18 |

| Consenting to sexual activity | 16–18 (depending upon U.S. state) |

Parents

Adolescence is a period of significant social development, characterized by evolving relationships with parents, peers, and romantic partners. One of the key changes during adolescence involves a renegotiation of parent-child relationships. As adolescents strive for more independence and autonomy during this time, different aspects of parenting become more salient. For example, parents’ distal supervision and monitoring become more important as adolescents spend more time away from parents and in the presence of peers. Parental monitoring encompasses a wide range of behaviors such as parents’ attempts to set rules and know their adolescents’ friends, activities, and whereabouts, in addition to adolescents’ willingness to disclose information to their parents (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Psychological control, which involves manipulation and intrusion into adolescents’ emotional and cognitive world through invalidating adolescents’ feelings and pressuring them to think in particular ways (Barber, 1996), is another aspect of parenting that becomes more salient during adolescence and is related to more problematic adolescent adjustment.

Cultural differences also shape these dynamics; Western cultures emphasize independence, while traditional cultures prioritize interdependence and respect for authority (Phinney & Ong, 2002). Despite these shifts, family relationships remain critical sources of support during adolescence. In traditional cultures, it is rare for frequent parent-teen conflict as the role of parent carries greater authority then Western cultures. If adolescents disagree with parents, they are less likely to express that given feelings of duty and respect (Phinney & Ong, 2002). Outside of Western cultures, interdependence is more highly valued than independence. While the journey to adulthood for Western adolescents prepares for independence, learning respect of authority and to role within a hierarchical group prepares traditional cultures for adult life of interdependence.

Peers

Peer relationships are a big part of adolescent development. The influence of peers can be both positive and negative as adolescents experiment together with identity formation and new experiences. As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families, and these peer interactions are increasingly unsupervised by adults. Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities, whereas adolescents’ notions of friendship increasingly focus on intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings. During adolescence, peer groups evolve from primarily single-sex to mixed-sex. Adolescents within a peer group tend to be similar to one another in behavior and attitudes, which has been explained as being a function of homophily (adolescents who are similar to one another choose to spend time together in a “birds of a feather flock together” way) and influence (adolescents who spend time together shape each other’s behavior and attitudes). One of the most widely studied aspects of adolescent peer influence is known as deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011), which is the process by which peers reinforce problem behavior by laughing or showing other signs of approval that then increase the likelihood of future problem behavior.

Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behavior than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or have conflictual peer relationships.

Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships (which are reciprocal dyadic relationships) and cliques (which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently), crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions (Brown & Larson, 2009). These crowds reflect different prototypic identities (such as jocks or brains) and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviors.

Romantic Relationships (Ob 2)

Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. Initially, same-sex peer groups that were common during childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups that are more characteristic of adolescence. Romantic relationships often form in the context of these mixed-sex peer groups (Connolly et al., 2000). Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized. Adolescents spend a great deal of time focused on romantic relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are more tied to romantic relationships (or lack thereof) than to friendships, family relationships, or school (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and adolescents’ emotional and behavioral adjustment.

Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescents’ sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality involves more than this narrow focus. For example, adolescence is often when individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender come to perceive themselves as such (Russell, Clarke, & Clary, 2009). Thus, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents’ experiment with new behaviors and identities.

Romantic relationships also emerge during adolescence as teens explore intimacy and connection. These relationships contribute to identity formation but may involve risks like teen dating violence (TDV), which includes psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. TDV affects a significant percentage of teens and is linked to long-term mental health issues like depression and post-traumatic stress (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; CDC, 2024). Programs promoting healthy relationships and addressing dating violence are essential for fostering socioemotional well-being.

Media

Media, particularly social media, plays a central role in adolescent development, offering both opportunities and risks. Teens spend an average of 8–9 hours daily on screens, with social media apps like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat dominating their usage (Rideout et al., 2022). While platforms can foster connection, self-expression, and identity exploration, they also expose teens to significant risks. Excessive screen time is linked to anxiety, depression, poor body image, and disordered eating behaviors, especially among girls (Twenge, 2020; Dane & Bhatia, 2023). Social media algorithms often amplify harmful content, such as unrealistic body standards or self-harm discussions, further exacerbating mental health challenges (Haidt, 2024). Cyberbullying and sexting are additional concerns; approximately 12% of teens report being coerced into sending explicit images, which can lead to legal consequences and long-term emotional distress (Patchin & Hinduja, 2020).

Despite these risks, social media can have positive effects when used responsibly. It allows marginalized teens to find supportive communities and promotes creative expression and peer motivation (Pew Research Center, 2022). Music consumption via media is another hallmark of adolescence, helping teens regulate emotions and explore identity (Saarikallio & Erkkila, 2007). To mitigate harms, experts recommend setting limits on screen time—especially before bed—encouraging tech-free zones at home, promoting media literacy education in schools, and fostering open conversations about online behavior (AAP, 2016; Murthy, 2023). Parents play a key role by modeling healthy habits and guiding teens toward balanced media use that supports their mental health and well-being.

Behavioral and Psychological Adjustment (Ob 2)

Self Concept

Self-concept, the cognitive aspect of identity, evolves during adolescence to include abstract qualities like fairness and loyalty, moving beyond the tangible traits of childhood (Harter, 2006). Adolescents develop their self-concept by comparing their traits and abilities to those of others. Harter (1983) identified key dimensions of self-concept: scholastic competence, social acceptance, athletic competence, physical appearance, behavioral conduct, and self-acceptance. These dimensions integrate into a coherent identity by late adolescence. Self-concept remains relatively stable from middle childhood to adolescence due to peer perception and niche-picking, where peers reinforce strengths and individuals seek environments that align with their skills (Kuzucu et al., 2014). Encouraging adolescents to explore new opportunities can help expand their self-concept.

Self-esteem, the emotional and motivational counterpart to self-concept, is linked to mental health. Low self-esteem increases risks for depression and social adjustment problems, such as smaller support networks (Masselink et al., 2018; Marshall et al., 2014). However, self-esteem generally improves during adolescence, with positive parental relationships, physical activity, and body image being key predictors of healthy self-esteem (Birkeland et al., 2012). Strategies like mindfulness, self-compassion, positive reinforcement, and encouragement of self-discovery can further enhance self-esteem and a sense of mastery (Marshall et al., 2015). No significant sex differences in average self-esteem levels have been reported (Masselink et al., 2017).

Theories of identity formation (Ob 10)

Erikson: Identity vs. Role Confusion

Erikson believed that the primary psychosocial task of adolescence was establishing an identity vs role confusion. Teens struggle with the question “Who am I?” This includes questions regarding their appearance, vocational choices and career aspirations, education, relationships, sexuality, political and social views, personality, and interests. Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and one’s life path. This stage typically occurs from ages twelve to eighteen years and is distinctive as a stage when individuals try out a variety of roles and personas in a journey to discover their individual identity. Developing an identity leads to strength and stability of identity. Failing to develop an identity results in role confusion, sometimes called diffusion, which leads to feeling fragmented or lost (Orenstein & Lewis, 2022). A strong sense of identity helps teenagers reject negative self-evaluations that don’t match their inner and outer experiences, reducing anxiety. As they explore their identity, adolescents consider their past experiences, societal expectations, and personal aspirations to establish their values and discover who they are.

During adolescence we experience psychological moratorium, where teens put on hold commitment to an identity while exploring the options. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research, suggests that few leave this age period with identity achievement, and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood (Côtè, 2006).

James Marcia (2010) expanded on Erikson’s theory by identifying four identity statuses based on the dimensions of exploration and commitment: identity diffusion, identity foreclosure, identity moratorium, and identity achievement. Identity diffusion is the least mature status, where individuals neither explore options nor commit to an identity. Common in children and early adolescents, those who persist in this status may feel aimless and disconnected, lacking a sense of purpose (Marcia, 1980). In identity foreclosure, individuals commit to an identity without exploration, often adopting values or roles imposed by parents or others. While foreclosure can provide initial stability, it limits personal growth unless followed by active exploration.

Identity moratorium describes individuals actively exploring potential identities without making a commitment, often experiencing an “identity crisis.” This stage, though emotionally challenging, fosters self-discovery and motivates progress toward identity achievement, where individuals commit to a coherent sense of self after exploration (Meeus, 2023). College is a common example of moratorium, as students explore academic and social roles. However, identity achievement is rarely finalized during adolescence; instead, individuals may cycle between moratorium and achievement—known as MAMA cycling—as they revisit and refine aspects of their identity over time. This dynamic process continues into adulthood as people adapt to changes in career, relationships, and values, highlighting the evolving nature of identity formation across the lifespan.

Table. Examples of Marcia’s identity status

| Diffusion | When asked what Tucker wants to do with his life, he says – I don’t know. He is a senior in high school and has not applied to any colleges or technical schools. He has a part-time job at the grocery story but does not earn enough to pay more than his car insurance and cell phone bill. He has not considered applying for a full-time job after high school either. He has not goals or plans right now. |

| Foreclosure | Elina, 17, is applying to the same college that her mother and grandmother both attended, and she has “decided” to major in business. She really hasn’t thought about whether or not she wants to go to college, or what she will do with a business degree. If asked about her plans she might say, “All the women in my family majored in business and then joined the family business. It worked for them and should work for me.” She has not questioned whether the life path chosen by the other women in her path, but simply accepts that her goal as one her family members have take. |

| Moratorium | Tina began to question going to church with her parents after taking a Introduction to World Religions course in college. She has always attended service with her parents since she was an infant. She instead wants to spend focus on her learning about all the different world religions and plans to visit several mosques, temples, and churches around the area to see what their worship services are like. Tina is actively exploring and considering what values, principles, and beliefs she wants to live by. |

| Achievement | Malik cast his vote for the presidential election the very first year he was allowed to vote. Before he did so, he carefully researched all the candidates and their positions on important issues. He took into account his own values and belief system. He voted for the candidate that best fit his beliefs and values for issues that were most important to him. |

Identity Development

During high school and the college years, teens and young adults move from identity diffusion and foreclosure toward the biggest gains in the development of identity are in college, as college students are exposed to a greater variety of career choices, lifestyles, and beliefs. This is likely to spur on questions regarding identity. A great deal of the identity work we do in adolescence and young adulthood is about values and goals, as we strive to articulate a personal vision or dream for what we hope to accomplish in the future (McAdams, 2013).

Marcia’s theory does not assume there is a set order to the identity statuses or that teenagers will experience all four identity statuses. Additionally, there is no assumption that a youth’s identity status is uniform across all aspects of their development. Youth may have different identity statues across different domains such as work, religion, and politics.

Developmental psychologists have researched several different areas of identity development and some of the main areas include:

- Religious identity: The religious views of teens are often similar to those of their families (KimSpoon et al., 2012). Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few completely reject the religion of their families.

- Political identity: The political ideology of teens is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party, but view themselves as more of an “independent.” Their teenage children are often following suit or become more apolitical (Côtè, 2006).

- Vocational identity: While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job, and often worked as an apprentice or part-time in such occupations as teenagers, this is rarely the case today. Vocational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. In addition, many of the jobs held by teens are not in occupations that most teens will seek as adults.

- Gender identity: This is also becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving. Some teens may foreclose on gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty, and they may adopt more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013).

- Ethnic identity refers to how people come to terms with whom they are based on their ethnic or racial ancestry. “The task of ethnic identity formation involves sorting out and resolving positive and negative feelings and attitudes about one’s own ethnic group and about other groups and identifying one’s place in relation to both” (Phinney, 2006, p. 119). When groups differ in status in the culture, those from the nondominant group have to be cognizant of the customs and values of those from the dominant culture. The reverse is rarely the case. This makes ethnic identity far less salient for members of the dominant culture. In the United States, those of European ancestry engage in less exploration of ethnic identity, than do those of non-European ancestry (Phinney, 1989). However, according to the U.S. Census (2012), more than 40% of Americans under the age of 18 are from ethnic minorities. For many ethnic minority teens, discovering one’s ethnic identity is an important part of identity formation.

Phinney’s model of ethnic identity formation is based on Erikson’s and Marcia’s model of identity formation (Phinney, 1990; Syed & Juang, 2014). Through the process of exploration and commitment, individuals come to understand and create an ethnic identity. Phinney suggests three stages or statuses with regard to ethnic identity:

1. Unexamined Ethnic Identity: Adolescents and adults who have not been exposed to ethnic identity issues may be in the first stage, unexamined ethnic identity. This is often characterized by a preference for the dominant culture, or where the individual has given little thought to the question of their ethnic heritage. This is similar to diffusion in Marcia’s model of identity. Included in this group are also those who have adopted the ethnicity of their parents and other family members with little thought about the issues themselves, similar to Marcia’s foreclosure status (Phinney, 1990).

2. Ethnic Identity Search: Adolescents and adults who are exploring the customs, culture, and history of their ethnic group are in the ethnic identity search stage, similar to Marcia’s moratorium status (Phinney, 1990). Often some event “awakens” a teen or adult to their ethnic group; either a personal experience with prejudice, a highly profiled case in the media, or even a more positive event that recognizes the contribution of someone from the individual’s ethnic group. Teens and adults in this stage will immerse themselves in their ethnic culture. For some, “it may lead to a rejection of the values of the dominant culture” (Phinney, 1990, p. 503).

3. Achieved Ethnic Identity: Those who have actively explored their culture are likely to have a deeper appreciation and understanding of their ethnic heritage, leading to progress toward an achieved ethnic identity (Phinney, 1990). An achieved ethnic identity does not

necessarily imply that the individual is highly involved in the customs and values of their ethnic culture. One can be confident in their ethnic identity without wanting to maintain the language or other customs.

The development of ethnic identity takes time, with about 25% of tenth graders from ethnic minority backgrounds having explored and resolved the issues (Phinney, 1989). The more ethnically homogeneous the high school, the less identity exploration and achievement (Umana-Taylor, 2003). Moreover, even in more ethnically diverse high schools, teens tend to spend more time with their own group, reducing exposure to other ethnicities. This may explain why, for many, college becomes the time of ethnic identity exploration. “[The] transition to college may serve as a consciousness-raising experience that triggers exploration” (Syed & Azmitia, 2009, p. 618).

It is also important to note that those who do achieve ethnic identity may periodically reexamine the issues of ethnicity. This cycling between exploration and achievement is common not only for ethnic identity formation, but in other aspects of identity development (Grotevant, 1987) and is referred to as MAMA cycling (moving back and forth between moratorium and achievement).

Bicultural/Multiracial Identity: Ethnic minorities must wrestle with the question of how, and to what extent, they will identify with the culture of the surrounding society and with the culture of their family. Phinney (2006) suggests that people may handle it in different ways. Some may keep the identities separate, others may combine them in some way, while others may reject some of them. Bicultural identity means the individual sees himself or herself as part of both the ethnic minority group and the larger society. Those who are multiracial, that is whose parents come from two or more ethnic or racial groups, have a more challenging task. In some cases their appearance may be ambiguous. This can lead to others constantly asking them to categorize themselves. Phinney (2006) notes that the process of identity formation may start earlier and take longer to accomplish in those who are not mono-racial.

Aggression and Antisocial Behavior (Ob 11)

Early, antisocial behavior leads to befriending others who also engage in antisocial behavior, which only perpetuates the downward cycle of aggression and wrongful acts.

Several major theories of the development of antisocial behavior treat adolescence as an important period. Patterson’s (1982) early versus late starter model of the development of aggressive and antisocial behavior distinguishes youths whose antisocial behavior begins during childhood (early starters) versus adolescence (late starters). According to the theory, early starters are at greater risk for long-term antisocial behavior that extends into adulthood than are late starters. Late starters who become antisocial during adolescence are theorized to experience poor parental monitoring and supervision, aspects of parenting that become more salient during adolescence. Poor monitoring and lack of supervision contribute to increasing involvement with deviant peers, which in turn promotes adolescents’ own antisocial behavior. Late starters desist from antisocial behavior when changes in the environment make other options more appealing. Similarly, Moffitt’s (1993) life-course persistent versus adolescent-limited model distinguishes between antisocial behavior that begins in childhood versus adolescence. Moffitt regards adolescent-limited antisocial behavior as resulting from a “maturity gap” between adolescents’ dependence on and control by adults and their desire to demonstrate their freedom from adult constraint. However, as they continue to develop, and legitimate adult roles and privileges become available to them, there are fewer incentives to engage in antisocial behavior, leading to resistance in these antisocial behaviors.

Academic achievement

Adolescents spend more waking time in school than in any other context (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). On average, high school teens spend approximately 7 hours each weekday and 1.1 hours each day on the weekend on educational activities. This includes attending classes, participating in extracurricular activities (excluding sports), and doing homework (Office of Adolescent Health, 2018). High school males and females spend about the same amount of time in class, doing homework, eating and drinking, and working. Academic achievement during adolescence is predicted by interpersonal (e.g., parental engagement in adolescents’ education), intrapersonal (e.g., intrinsic motivation), and institutional (e.g., school quality) factors. Academic achievement is important in its own right as a marker of positive adjustment during adolescence but also because academic achievement sets the stage for future educational and occupational opportunities. The most serious consequence of school failure, particularly dropping out of school, is the high risk of unemployment or underemployment in adulthood that follows. High achievement can set the stage for college or future vocational training and opportunities.

High School Dropouts: The status dropout rate refers to the percentage of 16 to 24 year-olds who are not enrolled in school and do not have high school credentials (either a diploma or an equivalency credential such as a General Educational Development [GED] certificate). The dropout rate is based on sample surveys of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, which excludes persons in prisons, persons in the military, and other persons not living in households. The dropout rate among high school students has declined from a rate of 12% in 1990, to 5% in 2022 (U.S. Department of Education, 2022). The status dropout rate declined between 2012 and 2022 for 16- to 24-year-olds who were Hispanic (7.9%), American Indian/Alaska Native (9.9%), Black (5.7%), White (4.3%), Asian (1.9 %). In 2022, the status dropout rate was higher for male 16- to 24-year-olds than for female 16- to 24-year-olds overall (6.3 vs. 4.3 percent).

Academics Across the Globe

The education and training that children receive in secondary school equip them with skills that are necessary to fully participate in society. Though the duration in each country vary, secondary education typically covers ages 12 to 17 and is divided into two levels: lower secondary education (spanning 3 to 4 years) and upper secondary education (spanning 2 to 3 years). However, UNICEF reported in 2021 that just two in three children of lower secondary school age attended either lower or upper secondary school, and only one in two children of upper secondary school age attended either upper secondary school or higher education.

In 2021, the global adjusted net attendance rates for lower, 65%, and upper secondary education, 52 % (WHO, 2022). Children from urban areas and the wealthiest households have much higher attendance rates in both lower and upper secondary education, with the gap growing wider at the upper secondary level. Globally more girls are attending secondary school. As measured by adjusted net attendance rates at the upper secondary level, 64 out of 109 countries with data available have a gender parity index over 1.03, meaning that in these countries, gender disparities in upper secondary attendance disadvantage boys. This could be mainly due to gender norms that drive boys to drop out to work and, in some contexts, may also be due to recruitment into illicit groups. For countries with gender parity index lower than 0.97 (girl disadvantage), two-thirds of them are in Eastern and Southern Africa or West and Central Africa. The gender gap in upper secondary attendance indicates that there is ample room for improvement to help every boy and girl to access education to thrive.

To find out more about academics in adolescence across the world, go to the UNICEF website on secondary education, https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/secondary-education/

Adolescent Health & Habits

Adolescents have more independence in what they eat and when they sleep compared to younger age groups. Furthermore, they are more autonomous via being able to drive. This section explores sleep, eating disorders, driving, and pregnancy.

Adolescent Sleep (Ob 9)

Sleep is vital for adolescents’ physical and brain development, as the human growth hormone is primarily secreted during deep sleep. However, increased screen use and social media at night have disrupted sleep patterns, leading to widespread sleep deprivation among teens. According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF), adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night to function best. While adolescents need 8–10 hours of sleep per night, only 40% of middle schoolers and 30% of high schoolers in the U.S. meet these guidelines, with just 20% achieving the optimal 9.25 hours (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). For older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and they are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include feeling too tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, having a depressed mood, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, they are at risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system (Weintraub, 2016). This chronic sleep deficit is linked to numerous negative outcomes, including impaired learning, memory loss, aggression, metabolism changes, poor self-esteem, and heightened risks for accidents and injuries. Despite sleeping more on weekends than school days, teens’ insufficient weekday sleep significantly impacts their academic performance and overall health.

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescents go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, but it also makes it difficult for them to get up in the morning. When they are awake too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, behavior, and academic achievement, while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also demonstrated. To support adolescents’ later sleeping schedule, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that school not begin any earlier than 8:30 a.m. Unfortunately, 83% of American schools begin their day earlier than 8:30 a.m. with an average start time of 8:03 a.m. (Sleep Foundation, 2022). Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later school times, and they have produced research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to better reflect sleep research. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools leaving many adolescents vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation.

Nutrition

Adequate adolescent nutrition is necessary for optimal growth and development. Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence future health, yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development. One of the reasons for poor nutrition is anxiety about body image, which is a person’s idea of how his or her body looks. The way adolescents feel about their bodies can affect the way they feel about themselves as a whole. Few adolescents welcome their sudden weight increase, so they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. Adding to the rapid physical changes, they are simultaneously bombarded by messages, and sometimes teasing, related to body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating that they encounter in the media, at home, and from their friends/peers (both in person and via social media). These changes may lead to eating disorders.

Eating Disorders (Ob 13)

Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2024). Eating disorders affect both genders, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia or an extreme concern with becoming more muscular. The prevalence of eating disorders in the United States is similar among Non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, African-Americans, and Asians, with the exception that anorexia nervosa is more common among Non-Hispanic Whites (Hudson et al., 2007; Wade et al., 2011; Stice et al, 2019).

Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2016). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women.

The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Table. Eating Disorder Diagnostic Criteria

| Diagnosis | Major Criteria |

| Anorexia | Significantly low body weight, significant weight and shape concerns |

| Bulimia Nervosa | Recurrent binge eating and compensatory behaviors (eg, purging, laxative use); significant weight and shape concerns |

| Binge eating disorder | Recurrent binge eating; at least 3 of 5 additional criteria related to binge eating (eg, eating large amounts when not physically hungry, eating alone due to embarrassment); significant distress |

Health Consequences of Eating Disorders: For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increases the risk for heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder (Arcelus et al., 2011). Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binge and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestives system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Eating Disorders Treatment: To treat eating disorders, adequate nutrition and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2016). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved in their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding the child. To eliminate binge eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

Anxiety and Depression (Ob 11)

Developmental models of anxiety and depression also treat adolescence as an important period, especially in terms of the emergence of gender differences in prevalence rates that persist through adulthood (Rudolph, 2009). Starting in early adolescence, compared with males, females have rates of anxiety that are about twice as high and rates of depression that are 1.5 to 3 times as high (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although the rates vary across specific anxiety and depression diagnoses, rates for some disorders are markedly higher in adolescence than in childhood or adulthood. For example, prevalence rates for specific phobias are about 5% in children and 3%–5% in adults but 16% in adolescents. Anxiety and depression are particularly concerning because suicide is one of the leading causes of death during adolescence.

Developmental models focus on interpersonal contexts in both childhood and adolescence that foster depression and anxiety (e.g., Rudolph, 2009). Family adversity, such as abuse and parental psychopathology, during childhood, sets the stage for social and behavioral problems during adolescence. Adolescents with such problems generate stress in their relationships (e.g., by resolving conflict poorly and excessively seeking reassurance) and select into more maladaptive social contexts (e.g., “misery loves company” scenarios in which depressed youths select other depressed youths as friends and then frequently co-ruminate as they discuss their problems, exacerbating negative affect and stress). These processes are intensified for girls compared with boys because girls have more relationship-oriented goals related to intimacy and social approval, leaving them more vulnerable to disruption in these relationships. Anxiety and depression then exacerbate problems in social relationships, which in turn contribute to the stability of anxiety and depression over time.

Mental Health

Adolescence is a critical period for mental health and physical well-being, marked by challenges such as sleep disorders, mental health struggles, and maladaptive eating behaviors. Eating disorders also emerge during adolescence, with diagnoses like anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder posing significant risks to physical and mental health (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Between 2018 and 2022, medical visits for eating disorders among U.S. youth under seventeen years more than doubled (Pastore et al., 2023). Risk factors include emotion regulation difficulties, societal pressures around body image, and perfectionism (Brytek-Matera, 2021; Barakat et al., 2023). Eating disorders can lead to severe health consequences across various body systems—including anemia, organ damage, and brain dysfunction—regardless of body weight (NIMH, 2017). Protective factors such as supportive family environments and positive body image can reduce risks, while cognitive behavioral therapy has proven effective for treatment (Hay, 2020; Vankerckhoven et al., 2024). Prevention strategies focused on resilience and healthy identity development are essential to addressing these complex issues. Sleep issues, including delayed sleep-wake phase disorder, insomnia, and obstructive sleep apnea, can disrupt adolescents’ physical and mental health (Moore & Meltzer, 2014). Mental health concerns are prevalent, with nearly 50% of adolescents experiencing a mental health disorder, including anxiety (31.9%) and depression (40.6%) (NIMH, 2017; CDC, 2024). Emotional regulation difficulties and adverse childhood experiences further heighten these risks (Young et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). Without adequate support, teens may turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms such as substance use or self-harm, which can increase suicide risk—the second leading cause of death among youth aged ten to twenty-four years (CDC, 2023). Suicide prevention efforts emphasize equitable healthcare access and socioemotional support to address disparities in risk factors among females and LGBTQ+ youth (Gaylor et al., 2023).

Teenage Drivers