1 Chapter 1: Intro to Lifespan Growth and Development

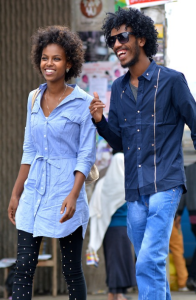

Photos Courtesy of Stefano Chiarelli (Left) and H.L.I.T (Right)

Objectives:

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to…

- Explain the study of human development.

- Define physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development.

- Differentiate periods of human development.

- Analyze your location in the life span.

- Contrast social classes concerning life chances.

- Explain the meaning of social cohort.

- Critique stage theory models of human development.

- Define culture and ethnocentrism and describe ways that culture impacts development.

- Explain the reasons scientific methods are more objective than personal knowledge.

- Contrast qualitative and quantitative approaches to research.

- Compare research methods noting the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- Differentiate between independent and dependent variables.

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Introduction (Ob 1, Ob 2, Ob 7)

Welcome to the study of human growth and development, commonly referred to as the “womb to tomb” course because it is the story of our journeys from conception to death. Human development is the study of how we change over time.

Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions; physical, cognitive, and psychosocial. Think about how you were 5, 10, or even 15 years ago. In what ways have you changed? In what ways have you remained the same? You have probably changed physically; perhaps you have grown taller and become heavier. However, you may have also experienced changes in the way you think and solve problems. Cognitive change is noticeable when we compare how 6-year-olds, 16-year-olds, and 46-year-olds think and reason, for example. Their thoughts about others and the world are probably quite different. Consider friendship for instance. The 6-year-old may think that a friend is someone with whom you can play and have fun. A 16-year-old may seek friends who can help them gain status or popularity. Also, the 46-year-old may have acquaintances but rely more on family members to do things with and confide in. These examples portray psychosocial change. Psychosocial development refers to developmental changes in emotions and psychological concerns as well as social relationships. We will explore these domains more thoroughly throughout the course.

Development is lifelong, and change is apparent across the lifespan (Baltes, 1987; Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006). Our academic knowledge of the lifespan has changed. At first, the focus of development was mostly in childhood and classifying developmental change as stages of development. Freud, Erikson, and Piaget are the three classic stage theorists whose models depict development as occurring in a series of predictable stages. Stage theorists see developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. This viewpoint is considered a stage theory. Freud and Piaget present a series of stages that mostly end during adolescence. For Freud, we enter the genital stage in which much of our motivation is focused on sex and reproduction, and this stage continues through adulthood. Piaget’s fourth stage, formal operational thought, begins in adolescence and continues through adulthood. Again, neither of these theories highlights developmental changes during adulthood. Furthermore, developmental psychologists have concerns and criticisms for sections of each of Freud’s and Piaget’s theories. Erikson, however, presents eight developmental stages throughout the lifespan describing our struggles with issues of independence, trust, and intimacy. Erikson is known as the “father” of developmental psychology for encompassing the entire lifespan in his theory, and his psychosocial theory forms a foundation for much of our discussion of psychosocial development.

| Stage theories had a certain appeal to an American culture experiencing a dramatic change in the early part of the 20th century. However, that sense of security was not without its costs; those who did not develop in predictable ways were often thought of as delayed or abnormal. Moreover, Freudian interpretations of problems in childhood development, such as autism, held that such difficulties were in response to poor parenting. Imagine the despair experienced by mothers accused of causing their child’s autism by being cold and unloving. It was not until the 1960s that more medical explanations of autism began to replace Freudian assumptions. |

Although the theories of stage theorists (Piaget, Freud, and Erikson) see development as discontinuous development, lifespan theorists understand that development can be viewed and measured in different ways. Other theorists, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more advanced skills.

An example in nature depicting continuous development. Photo Courtesy of Pixabay

An example in nature depicting discontinuous development. Photo Courtesy of PublicDomainPictures

Development is multidirectional. Humans change in many directions. We may show gains in some areas of development while showing losses in other areas. Every change, whether it is finishing high school, getting married, or becoming a parent, entails both growth and loss. Today we are more aware of the variations in development. We no longer assume that those who develop in predictable ways are normal and those who do not are abnormal. So the assumption that early childhood experiences dictate our future is also being called into question. Instead, we have come to appreciate that growth and change continue throughout life and experience continues to have an impact on who we are and how we relate to others. Moreover, we recognize that adulthood is also a dynamic period of life marked by continued cognitive, social, and psychological development.

Development is multidisciplinary. Developmental psychology is related to other applied fields. The field informs several applied fields in psychology, including, educational psychology, psychopathology, and forensic developmental psychology. It also complements several other basic research fields including social psychology, cognitive psychology, gerontology, and child development. Many academic disciplines contribute to the study of life span, and this course is offered in some schools as psychology; in other schools, it is taught under sociology or human development. Lastly, it draws from the theories and research of several scientific fields, and is made up of contributions from researchers in the areas of health care, anthropology, nutrition, child development, biology, gerontology, psychology, and sociology among others. Consequently, the stories provided in this text are rich and well-rounded and the theories and findings can be part of a collaborative effort to understand human lives.

Development occurs in many contexts. Our journeys through life are more than biological; they are shaped by culture, history, economic, and political realities as much as they are influenced by physical change. This is an exciting and practical course because it is about us and those with whom we live and work. One of the best ways to gain perspective on our own lives is to compare our experiences with that of others. By periodically making cross-cultural and historical comparisons and by presenting a variety of views on issues such as healthcare, aging, education, gender, and family roles, we hope to give you many eyes with which to see your development. Being self-conscious can enhance our ability to think critically about the systems we live in and open our eyes to new courses of action to benefit the quality of life. Moreover, knowing about other people and their circumstances can help us live and work with them more effectively. An appreciation of diversity enhances the social skills needed in nursing, education, or any other field.

Many Contexts (Ob 5, Ob 6, Ob 8)

Development is multicontextual. People are best understood in context. What is meant by the word “context”? It means that we are influenced by when and where we live, and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. Robert Sternberg, a famous psychologist whose theory of intelligence is based on three factors. Sternberg describes a type of intelligence known as “contextual” intelligence as the ability to understand what is called for in a situation (Sternberg, 1996). The key here is to understand that behaviors, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture. Our concerns are such because of who we are socially, where we live, and when we live; they are part of a social climate and set of realities that surround us. Our social locations include cohort, social class, gender, race, ethnicity, and age. Let us explore two of these: cohort and social class.

The Cohort Effect (Ob 6)

One crucial context that is sometimes mistaken for age is the cohort effect. A cohort is a group of people who are born at roughly the same period in a particular society. Cohorts share histories and contexts for living. Members of a cohort have experienced the same historical events and cultural climates which have an impact on the values, priorities, and goals that may guide their lives. Consider a young boy’s concerns as he grows up in the United States during World War II. What his family buys is limited by their small budget and by a national program set up to ration food and other materials that are in short supply because of the war. He is eager rather than resentful about being thrifty and sees his actions as meaningful contributions to the good of others. As he grows up and has a family of his own, he is motivated by images of success tied to his experience: a successful man is one who can provide for his family financially, who has a wife who stays at home, and children who are respectful but enjoy the luxury of days filled with school and play without having to consider the burdens of society’s struggles. He marries soon after completing high school, has four children, works hard to support his family, and can do so during the prosperous postwar economics of the 1950s in America. However, economic conditions change in the mid-1960s and through the 1970s. His wife begins to work to help the family financially and to overcome her boredom with being a stay-at-home mother. The children are teenagers in a very different social climate: one of social unrest, liberation, and challenging the status quo. They are not sheltered from the concerns of society; they see television broadcasts in their living room of the war in Vietnam, and they fear the draft. Moreover, they are part of a middle-class youth culture that is very visible and vocal. His employment as an engineer eventually becomes difficult as a result of downsizing in the defense industry. His marriage of 25 years ends in divorce. This is not a unique personal history; instead, it is a story shared by many members of his cohort. Historic contexts shape our life choices and motivations as well as our final assessments of success or failure during our existence.

| Generational Cohorts in U.S. | Birth Years | Defining Technology | Broad traits |

| Greatest Generation | 1900-1929 | Radio | Great Depression survival, integrity, work ethic, prudence |

| Silent Generation | 1929-1945 | Fax machine | Loyalty, respect for authority, sacrifice |

| Baby Boomers: Traditionals | 1946-1954 | Personal computer | Social causes, hardworking and long hours, idealistic |

| Baby Boomers: Generation Jones | 1955-1964 | Laptop computer | Pragmatic, need to complete and get ahead |

| Generation X | 1965-1979 | Mobile phone | Self-reliance, work/life balance, skepticism |

| Generation Y (Millennials) | 1980-1994 | Immediacy, confidence, tolerance, social connection | |

| iGen/Gen Z | 1995-2012 | Smartphone | More tolerant of others, more cautious, more social media useage |

| Gen Alpha | 2013-2025 | ? | ? |

Adapted from O'Neill, M. (2010), Generational Preferences: A Glimpse into the Future Office, and Twege, J. (2017), iGen, Why Today's Super-Connected Kids are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy ...., and Brokaw, T. (1998) The Greatest Generation

Consider your cohort. Can you identify it? Does it have a name and if so, what does the name imply? To what extent does your cohort shape your values, thoughts, and aspirations? (Some cohort labels popularized in the media for generations in the United States include Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation M.)

Consider your cohort. Can you identify it? Does it have a name and if so, what does the name imply? To what extent does your cohort shape your values, thoughts, and aspirations? (Some cohort labels popularized in the media for generations in the United States include Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation M.)

Socioeconomic Status (Ob 5)

Another context that influences our lives is our social standing, socioeconomic status, or social class. Socioeconomic status is a way to identify families and households based on their shared levels of education, income, and occupation. While there is undoubtedly individual variation, members of a social class tend to share similar lifestyles, patterns of consumption, parenting styles, stressors, religious preferences, and other aspects of daily life. (Consider, for example, some terms that have been used in marketing to refer to different consumer groups: the “truck and trailer” or the “pool and poodle” group referring to working class and upper-middle-class groups.) All of us born into a class system or are socially located and may move up or down depending on a combination of both socially and individually created limits and opportunities. Below is a model of the class system identified in the United States (Gilbert 2003; Gilbert & Kahl, 1998), a description of these social classes, and a partial listing of the impact that social class can have on individual and family life (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

Model of Social Class Based on Socioeconomic Status

Upper Class: This group makes up about 1 percent of the population in the United States. They own substantial wealth and after-tax annual family income of $200,000 to $750,000 (DeNavas-Walt & Cleveland, 2002). The upper class is subdivided into “upper-upper” and “lower-upper” categories based on how money and wealth were acquired. The “upper-upper class” (0.5%) has money from investments or inheritance and tend to be stewards of the family fortune. This “old money” brings a sense of polish and sophistication now shared by those with “new money.” The newly rich (0.5%) have made their fortunes as personalities in sports and media or as entrepreneurs. Members of the newly rich tend to flaunt their wealth; a practice looked upon with disdain by old money.

Upper Middle Class: About 14 percent of the population in the United States is considered upper middle class. Income levels are more often between $100,000 and $200,000 annually and hold professional degrees that involve education beyond a 4-year bachelor’s degree. One of the distinctions made between the middle-class overall and members of the working class is that members of the middle class have occupations in which they are paid for their education and expertise. These “white-collar” workers (a term that originally referred to the distinction between what office workers wore to work as opposed to factory workers designated as “blue collar” workers) hold professional positions such as physicians or attorneys and as professionals enjoy a good deal of freedom and control over their occupations. They determine the regulations of their work through professional organizations (such as the American Medical Association). Having a sense of autonomy or control is a critical factor in experiencing job satisfaction and personal happiness and ultimately health and well-being (Weitz, 2007).

US Social Class Ladder

| class | % of population | Typical annual income | education |

| Upper | 1% | 1,000,000+ | Prestigious university |

| Upper-middle | 14% | 125,000+ | College or university, sometimes postgraduate |

| middle | 34% | 60,000 | High school or college |

| Working class | 30% | 36,000 | High school |

| Working poor | 15% | 19,000 | High school and some high school |

| underclass | 5% | 12,000 | Some high school |

Image from Pixabay

Adapted from https://content.stg-openclass.com/eps/sanvan/api/item/b24b022b-f37a-4b3e-80f7-1cbe688c8b4b/1/file/henslin_writing_space_prod_test03302015/OPS/text/chapter-08/ch8_sec_02.xhtml

Middle Class: Another 34 percent of the population is considered middle class. These individuals work in lower-paying, less autonomous white-collar jobs such as teaching and nursing or as lower-level managers. Members of the middle class may hold 2 or 4-year degrees, but often from less prestigious, state-supported schools. Their income typically ranges between $25,000 and $75,000 annually. They own less property and have less discretionary income than members of the upper-middle and upper class and yet they may share the values and standards held by the upper-middle class. Acquiring larger homes, newer vehicles, and pursuing travel, paying for health care and dental expenses often means taking on substantial debt. This problem is not unique to the United States, however.

Consider this excerpt from a British newspaper describing today’s “impoverished professionals” in which a couple goes to dinner before a movie and realizes that they have no cash. Then here come the credit cards!

“I’ve brought all the cards . . . the trouble is, I can’t remember which ones are up to their limit . . .Go to a cash machine? Forget it. Both our current accounts have been frozen. Welcome to the world of middle-class debt . . . On paper, my husband and I are what is known in polite parlance as “comfortably off.” In reality, we have no money. Anything that comes in goes immediately on debt repayment . . . That and paying the nanny so we can both go out to work and earn more money for more debt repayment. An Impoverished Professional, I call myself. Moreover, there are plenty of us out there.”

The average amount of credit card debt in American households is $5,551 (Sullivan, 2018). Additionally, 144 million Americans who carry an “all-purpose” credit card, while only 55 million pay their entire balance off each month. The industry refers to these people as “deadbeats” and prefers the almost 90 million customers who extend their payment over months. These “revolvers” create nearly $30 billion in profits for the industry (Frontline, 2004). Carrying debt can be extremely stressful and have a negative effect on health and social well-being. The consequences of such debt are still being explored.

The Working Class: Thirty percent of Americans are considered members of the working class. The working class is comprised of those working in occupations such as retail, clerical or factory jobs. Their jobs are typically routine and more heavily supervised than those of the middle class and require less formal education than do white-collar jobs. Members of the working class are subject to plant closings, lower pay, and more frequent layoffs, and may rely on fewer workers contributing to the family income. Fewer earners and less job stability impact not only family income, but it also impacts the likelihood of having adequate health care. Being employed does not ensure adequate healthcare; in fact, 69 percent of the 45 million Americans who lack any medical insurance live in households where there is at least one full-time employee (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2004). Americans who are self-employed or working in companies with fewer than 200 employees are less likely to have health insurance benefits than those who work in companies with 200 or more employees (Weitz, 2007). Also, the cost of obtaining even minimal health insurance as an individual is often prohibitive.

Social class differences go beyond financial concerns, however. In a classic study on parenting styles and social class, Kohn (1977) found that working-class parents emphasize obedience, honesty, and conformity in their children while middle-class parents valued independence, initiative, and self-reliance. These differences are attributed to the expectations made of parents as workers; blue-collar workers are rewarded for conformity while white-collar workers are rewarded for their initiative.

The Working Poor: Fifteen percent of Americans are categorized as the working poor. These people live near the poverty level and hold seasonal or temporary jobs as unskilled laborers. This includes migrant farm workers, temporary employees in service industries such as restaurants or retail typically for minimum wage. The poor and working poor experience many of the same problems that can have an impact on development. We will examine this list after describing the next social class.

The Underclass: Approximately five percent of Americans are part of the underclass described as temporary workers, part-time workers, those who are chronically unemployed or underemployed (Gilbert, 2003). They may receive some government assistance and tend to be looked down upon by other members of society. The national unemployment rates in the United States is around six percent, ranging from 3 to 10 percent over the past 20 years (USBLS, 2018). Many of the underclass are children or are disabled. It is estimated that there are about 3.5 million homeless people in the United States and 1.5 of them are children (Urban Institute, 2000). Life on the streets can be hazardous involving addiction, deceit, violence, sexual assault, and prostitution or “survival sex” which refers to exchanging food for shelter (Davis, 1999).

Other Consequences of Poverty: Poverty level is an income amount established by the Social Security Administration that is based on a formula called the “thrifty food plan” that allows one-third of income for food. It is based on a set of income thresholds set by the government that varies by family size (United States Census Bureau, 2016). Those living at or near poverty level may find it extremely difficult to sustain a household with this amount of income. Buying the least expensive, most filling foods typically means buying foods high in fat, starch, and sugar. Living in inadequate housing with the fear of eviction or poor plumbing and disruptive neighbors can also be stressful. Poverty is associated with poor health and a lower life expectancy due to a deficient diet, less healthcare, more significant stress, working in more dangerous occupations, higher infant mortality rates, inadequate prenatal care, iron deficiencies, greater difficulty in school, and many other problems. Members of the middle class may fear losing status, but the poor may have more significant concerns over losing housing. Moreover, while those in the middle class are more likely to use shopping or travel as a way to cope with stressors, the poor are more likely to eat or smoke in response to stress (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

![]()

Think about how social class might impact the life of someone with whom you are working in a hospital, school, or another setting. What should you consider in order to be most effective in helping that person or family?

Many Cultures (Ob 8)

Culture is often referred to as a blueprint or guideline shared by a group of people that specifies how to live. It includes ideas about what is right and wrong, what to strive for, what to eat, how to speak, what is valued, as well as what kinds of emotions are called for in certain situations. Culture teaches us how to live in a society and allows us to advance because each new generation can benefit from the solutions found and passed down from previous generations. Culture is learned from parents, schools, churches, media, friends, and others throughout a lifetime. The kinds of traditions and values that evolve in a particular culture serve to help members function in their society and to value their society. We tend to believe that our own culture’s practices and expectations are the right ones – this is ethnocentrism. For example, if English say that American’s drive on the wrong side of the road (or vice versa), this is one’s culture as a frame of reference. Believing one’s culture is superior to another (ethnocentrism) is a normal byproduct of growing up in a culture. Ethnocentrism becomes a roadblock when it inhibits understanding of cultural practices from other societies. On the other hand, when an individual can view sitatuiosn outside the lens of their own culture, they are practicing cultural relativism. Cultural relativity is an appreciation for cultural differences and the understanding that cultural practices are best understood from the standpoint of that particular culture.

Culture is an essential context for human development and understanding development requires being able to identify which features of development are culturally based. This understanding is somewhat new and still being explored. So much of what developmental theorists have described in the past has been culturally bound and difficult to apply to various cultural

Photo Courtesy of Pixabay

Even the most biological events can be viewed in cultural contexts that vary immensely. Consider two very different cultural responses to menstruation in young girls. In the United States, girls in public school often receive information on menstruation in around 5th grade. The extent to which they are also taught about sexual intercourse, reproduction, or sexually transmitted infections depends on the policy of the school district guided by state and local community standards and sentiments. However, menstruation is addressed, and girls receive information and a kit containing feminine hygiene products, brochures, and other items. For example, menstruation is interpreted as an event that can affect the mood of a young girl and temporarily render her difficult, hostile, or simply hard to be around. However, she is encouraged to have a “happy” period with this product and is also encouraged to wish her friends a happy period as well through a product-sponsored positive message marketing. Contrast this with the concern that a lack of sanitary “towels” or feminine napkins causes many girls across Africa to miss more than a month of school each year during menstruation. Education is essential in these countries for moving ahead, and the lack of sanitary towels places these girls at a tremendous educational disadvantage. The one-dollar price tag on towels is prohibitive in countries such as Kenya where most families earn about 54 cents per day. The lack of towels also results in unsanitary practices such as the use of blankets or old cloths to manage the menstrual flow. In some parts of Africa, reusable or washable sanitary towels are used, but in countries such as Kenya where there is little water, this would not be a solution. Moreover, in instances where towels were donated and given out without educating girls on how to use them, girls have folded them up and used them as tampons, a practice that can lead to acute infection (Mawathe, 2006).

Think of other ways culture may have affected your development. How might cultural differences influence interactions between teachers and students, nurses and patients, or other relationships?

Periods of Development (Ob 3)

Think about the life span and make a list of what you would consider the periods of development. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: childhood, adulthood, and old age. Or maybe four: infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Developmentalists break the lifespan into 10 periods of development:

-

-

-

-

- Prenatal Development

- Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Early Childhood

- Middle Childhood

- Adolescence

- Emerging Adulthood

- Early Adulthood

- Middle Adulthood

- Late Adulthood

- Death and Dying

-

-

-

| Age Period | Description |

|---|---|

| Prenatal | Starts at conception and continues through implantation in the uterine wall by the embryo and ends at birth. |

| Infancy and Toddlerhood | Starts at birth and continues to two years of age |

| Early Childhood | Starts at two years of age until six years of age |

| Middle and Late Childhood | Starts at six years of age and continues until the onset of puberty |

| Adolescence | Starts at the onset of puberty until 18 |

| Emerging Adulthood | Starts at 18 until 25 |

| Early Adulthood | Starts at 25 until 40-45 |

| Middle Adulthood | Starts at 40-45 to 60-65 |

| Late Adulthood | Starts at 65 onward |

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adulthood that will be explored in this text. The text takes a chronological approach with an organization from each of these periods. So, while both an 8-month-old and 8-year-old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different, and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive. The same is true of an 18-year-old and an 80-year-old, both considered adults. We will discover the distinctions between being 28 or 48 as well. However, first, here is a brief overview of the stages.

Prenatal Development

Photo Courtesy of WikiCommons

Conception occurs, and development begins. Prenatal Development is the first period which will be discussed in chapter 3, and is considered human development within the womb. All of the major structures of the body are forming, and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to congenital disabilities), and labor and delivery are primary concerns. You will read more about Prenatal Development in chapter 3.

Infancy and Toddlerhood

Photo Courtesy of George Ruiz

The first year and a half to two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change, this period is known as infancy and toddlerhood. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but poor vision, is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleeping schedules to a continually moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child. You will read more about Infancy and Toddlerhood in chapter 4.

Early Childhood

Photo Courtesy of Governor Tom Wolf

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years consisting of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a 3 to 5-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may have initially had unusual conceptions of size, time, space, and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a 4-year-old’s sense of guilt for doing something that brings the disapproval of others. You will read more about Early Childhood in chapter 5.

Middle Childhood

Photo Courtesy of Alternative Break Program

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood, and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children can refine their motor skills at this point in life. Moreover, children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students. You will read more about Middle Childhood in chapter 6.

Adolescence

Photo Courtesy of Ray in Manila

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. Adolescence typically spans around the ages 11 to 18. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at higher risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. You will read more about Adolescence in chapter 7.

Emerging Adulthood

Photo Courtesy of COD Newsroom

Emerging Adulthood is considered a period of development between adolescence and adulthood, lasting roughly from ages 18 to 25. It is a time when we are at our physiological peak but are most at risk for involvement in violent crimes and substance abuse. Five features make emerging adulthood distinctive: identity explorations, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood, and a sense of immense possibilities for the future. Emerging adulthood is found mainly in developed countries, where most young people obtain tertiary education and median ages of entering marriage and parenthood are around 30. You will read more about Emerging Adulthood in chapter 8.

Early Adulthood

Photo Courtesy of Pixabay

The mid-twenties and thirties are often thought of as early adulthood. (Students who are in their mid-30s tend to love to hear that they are a young adult!) It is a time of focusing on the future and putting much energy into making choices that will help one earn the status of a full adult in the eyes of others. Love and work are the primary concerns at this stage of life. You will read more about Early Adulthood in chapter 9.

Middle Adulthood

Photo Courtesy of Pixabay

The late thirties through the mid-sixties is referred to as middle adulthood. This is a period in which aging that began earlier becomes more noticeable and a period at which many people are at their peak of productivity in love and work. It may be a period of gaining expertise in specific fields and being able to understand problems and find solutions with greater efficiency than before. It can also be a time of becoming more realistic about possibilities in life previously considered; of recognizing the difference between what is possible and what is likely. This is also the age group hardest hit by the AIDS epidemic in Africa resulting in a substantial decrease in the number of workers in those economies (Weitz, 2007). You will read more about Middle Adulthood in chapter 10.

Late Adulthood

Photo Courtesy of Rosanetur

This period of the life span has increased in the last 100 years, particularly in industrialized countries. Late adulthood is sometimes subdivided into two categories such as the “young old” (65-84) and “oldest old” (85+). One of the primary differences between these groups is that the young old may still working, still relatively healthy, and still interested in being productive and active. The “oldest old” remain productive and active, and the majority continues to live independently, but risks of the diseases of old age such as arteriosclerosis, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease increase substantially for this age group. Issues of housing, healthcare, and extending active life expectancy are only a few of the topics of concern for this age group. A better way to appreciate the diversity of people in late adulthood is to go beyond chronological age and examine whether a person is experiencing optimal aging (like the gentleman pictured above who is in very good health for his age and continues to have an active, stimulating life), normal aging (in which the changes are similar to most of those of the same age), or impaired aging (referring to someone who has more physical challenge and disease than others of the same age). You will read more about Late Adulthood in chapter 11.

Death and Dying

Photo Courtesy of Jakub T. Jankiewicz

This topic is seldom given the amount of coverage it deserves. Of course, there is a certain discomfort in thinking about death, but there is also absolute confidence and acceptance that can come from studying death and dying. We will examine the physical, psychological, and social aspects of death, exploring grief or bereavement, and addressing ways in which helping professionals work in death and dying. Moreover, we will discuss cultural variations in mourning, burial, and grief.

Research Methods: How do we know what we know? (Ob 9)

An essential part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Not long ago a friend said to me that he did not trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is precisely what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and parenting advice. So, think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Personal Knowledge

How do we know what we know?

Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. . .Okay. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your history (experiential reality) or based on what others have told you or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry.

Read the following sentence aloud:

Paris in the

the spring

Are you sure that is what it said? Reread it:

Paris in the

the spring

If you read it differently the second time (adding the second “the”) you just experienced one of the problems with personal inquiry; that is, the tendency to see what we believe. Our assumptions very often guide our perception; consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. This problem may be a result of cognitive ‘blinders,’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right, and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence. Popper, a famous philosopher of science, suggests that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). A theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. Moreover, much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is right with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons and guard against bias. First researchers taking a scientific approach define concepts being studied and call them variables. A variable is the information you are collecting or anything that changes in value (e.g., asking hours slept last night is a variable, so is measuring your height, or asking you how extroverted you are). Variables must be operationalized. Operalization of variables is when the researcher specifically defines how the concept/construct is going to be measured in the study. For example, if we are interested in studying marital satisfaction, we have to specify what marital satisfaction means or what we are going to use as an indicator of marital satisfaction. What is something measurable that would indicate some level of marital satisfaction? Would it be the amount of time couples spend together each day? Or eye contact during a discussion about money? Or maybe a subject’s score on a marital satisfaction scale. Each of these is measurable, but these may not be equally valid (authentic) or accurate indicators of marital satisfaction. These are the kinds of considerations researchers must make when working through the design. We will take a look at different methods that can be used to measure variables later in this section.

What do you think? How would you operationalize marital satisfaction? Romantic love? Extroversion?

What if you just ask people around you about their marital satisfaction? What if you only ask newly weds? Both of these could be considered sampling bias. An additional consideration to studies is examining the possibility of sampling bias. Scientific research works to avoid sampling bias that might come from only using personal experiences or only asking friends and family about what variables you are interested in studying (e.g., sleep, marital satisfaction, extroversion). One technique used to avoid sampling bias is to select participants for a study in a random way. This means using a technique to ensure that all members have an equal chance of being selected. Simple random sampling may involve using a set of random numbers as a guide in determining who is to be selected. For example, if we have a list of 400 people and wish to randomly select a smaller group or sample to be studied, we use a list of random numbers and select the case that corresponds with that number (Case 39, 3, 217, etc.). This is preferable to asking only those individuals with whom we are familiar to participate in a study; if we conveniently chose only people we know, we know nothing about those who had no opportunity to be selected. Many more elaborate techniques can be used to obtain samples that represent the composition of the population we are studying. However, even though a randomly selected representative sample is preferable, it is not always used because of costs and other limitations. (As a consumer of research, however, you should know how the sample was obtained and keep this in mind when interpreting results.)

Scientific Methods (Ob 9)

The scientific method is the set of assumptions, rules, and procedures scientists use to conduct research.

One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making your findings available to others (both to share information and to have your work scrutinized by others)

Your findings can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest and through this process, a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. Moreover, it typically involves quantitative research or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied. Many academic journals publish reports on studies conducted in this manner and an excellent way to become more familiar with these steps is to look at journal articles which will be written in sections that follow these steps. For example, after a section entitled “Statement of the Problem,” you might find a second section entitled, “Literature Review.” Other headings will reflect the stages of research mentioned above.

Another model of research referred to as qualitative research may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest

- Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as the study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed relevant by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student, and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers are to be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them, and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic, and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

Types of Studies (Ob 10, Ob 11)

Not all studies are designed to reach the same goal. Descriptive studies focus on describing an occurrence. Some examples of descriptive questions include “How much time do parents spend with children?”; “How many times per week do couples have intercourse?”; or “When is marital satisfaction greatest?”. Descriptive studies can be exploratory or designed to share information from non-experimental designs (studies that do not have an experimental design which will be explained soon). Explanatory studies are efforts to answer the question “why” such as “Why have rates of divorce leveled off?” or “Why are teen pregnancy rates down?” Evaluation research is designed to assess the effectiveness of policies or programs. For instance, research might be designed to study the effectiveness of safety programs implemented in schools for installing car seats or fitting bicycle helmets. Do children wear their helmets? Do parents use car seats properly? If not, why not?

Just as there are different goals of research, there are also different research designs that correspond to the research goal. The following is a comparison of research methods or techniques used to describe, explain, or evaluate. Each of these designs has strengths and weaknesses and is sometimes used in combination with other designs within a single study.

Research methods/techniques (Ob 10, Ob 11)

Observational studies involve watching and recording the actions of participants. Observational studies are typically for descriptive or non-experimental designs. Observations may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play at a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event as a participant (such as attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and recording the slogans on the walls, the structure of the meeting, the expressions commonly used, etc.). The researcher may be a participant or a non-participant. What would be the strengths of being a participant? What would be the weaknesses? Consider the strengths and weaknesses of not participating. In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. What people do and what they say they do are often very different. A significant weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. Children tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect) and may not survey well.

Example of observational study of parent-child interactions for an observational study Photo Courtesy of Alisa Beyer

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Case studies are used typically for descriptive research. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. Moreover, they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their standard practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison. (Read “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” by Dr. Oliver Sacks as an excellent example of the case study approach. The book shares case studies of individuals with interesting neurological disorders like patients who no longer recognize people or common objects.)

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to individuals because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. Surveys gather information from many individuals in a short period, which is the most significant benefit for surveys. Additionally, surveys are inexpensive to administer. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many independent and dependent variables in a relatively short period. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior. Of course, surveys can be designed in several ways depending on the research goal. They may include forced choice questions (must pick from selection) and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. Surveys can also be set up for an experimental design (method described later).

Photo Courtesy of Flickr

One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So, a lot of time and effort should be placed on the construction of survey items. One of the benefits of having forced-choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. The analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed differently. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report or what people say they do rather than on observation, and this can limit accuracy. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior. Another problem is that respondents may lie because they want to present themselves in the most favorable light, known as social desirability. They also may be embarrassed to answer truthfully or are worried that their results will not be kept confidential.

Interviews involve the participant being directly questioned by a researcher. Depending on the goal of the study, interviews can be used for experimental, but are typically used in descriptive or non-experimental designs. Interviewing participants on their behaviors or beliefs can solve the problem of misinterpreting the questions posed on surveys. The examiner can explain the questions and further probe responses for greater clarity and understanding. Older children and adults are commonly asked to use language to discuss their thoughts and knowledge about the world. These verbal report paradigms are among the most widely used in psychological research. For instance, a researcher might present a child with a vignette or short story, and the child would be asked to give their thoughts and beliefs. Although this can yield more accurate results, interviews take longer and are more expensive to administer than surveys. Participants can also demonstrate social desirability, which will affect the accuracy of the responses.

Psychophysiological Assessment may also be completed and may provide information from infants, and very young children are unable to talk about their thoughts and behaviors. These assessments involve systematic processes or testing to provide information about participants’ behaviors or capabilities. During psychophysiological assessments, researchers may also record psychophysiological data, such as measures of heart rate, hormone levels, or brain activity to help explain development. These measures may be recorded by themselves or in combination with behavioral data to understand the bidirectional relations between biology and behavior better. Special equipment has been developed to allow researchers to record the brain activity of the very young.

One manner of understanding associations between brain development and behavioral advances is through the recording of event-related potentials (ERPs). ERPs are recorded by fitting a research participant with a stretchy cap that contains many small sensors or electrodes. These electrodes record tiny electrical currents on the scalp of the participant in response to the presentation of stimuli, such as a picture or a sound. The use of ERPs has provided valuable insight as to how infants and children understand the world around them.

Photo courtesy of Siman Fraser University

| Research with Psychophysiological Assessment Webb, Dawson, Bernier, and Panagiotides (2006) examined face and object processing in children with autism spectrum disorders, those with developmental delays, and those who were typically developing. The children wore electrode caps and had their brain activity recorded as they watched still photographs of faces of their mother or a stranger, and objects, including those that were familiar or unfamiliar to them. The researchers examined differences in face and object processing by group by observing a component of the brainwaves. Findings suggest that children with autism are in some way processing faces differently than typically developing children and those with more general developmental delays. |

Secondary analysis involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices, or preferences. There are several data sets available to those who wish to conduct this type of research. For example, the U. S. Census Data is available and widely used to look at trends and changes taking place in the United States. Several other agencies collect data on family life, sexuality, and many other areas of interest in human development. The researcher conducting secondary analysis does not have to recruit subjects but does need to know the quality of the information collected in the original study.

A specific type of secondary analysis is content analysis. Content analysis involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics or other materials to explore patterns or themes in culture. An example of content analysis is the classic history of childhood by Aries (1962) called “Centuries of Childhood” or the analysis of television commercials for sexual or violent content. Passages in text or programs that air can be randomly selected for analysis as well. Again, one advantage of analyzing work such as this is that the researcher does not have to go through the time and expense of finding respondents, but on the other hand, the researcher cannot know how accurately the media reflects the actions and sentiments of the population.

Experimental research designs (Ob 11, Ob 12)

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables) in a controlled setting in efforts to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. Researcher use an experimental design to determine cause and effect. In order to draw causal conclusions, the researchers must have an independent variable and a dependent variable. The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable.

Three conditions must be met in order to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs are useful in meeting these conditions.

-

-

- The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, when one is altered, the other changes in response. (For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.)

- The cause must come before the effect. Experiments involve measuring subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So, we would measure the subjects’ level of stress before introducing exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there has been a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events which makes understanding causality problematic with these designs.)

- The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown variables are causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would make sure that our subjects’ diets were held constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, the diet might be creating a change in stress level rather than exercise.

-

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or subset of a population) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two groups: the experimental group or the control group. The experimental group is the group that is going to be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher is introducing as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison and is going to have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are in a better position to suggest that the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable. The basic experimental model looks like this:

| Measure DV | Introduce IV | Measure DV | ||

| Sample is | Experimental Group | X | X | X |

| Randomly→ | ||||

| Assigned | Control Group | X | – | X |

Basic experimental model

The significant advantage of the experimental design is that of helping to establish cause and effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty of translating much of what concerns us about human behavior into a laboratory setting. I hope this brief description of experimental design helps you appreciate both the difficulty and the rigor of conducting an experiment.

Developmental research designs (Ob 11)

Developmental designs are techniques used in lifespan research (and other areas as well). These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

Cross-sectional research involves beginning with a sample that represents a cross-section of the population. Participants are divided into groups based on demographics (such as different age groups). Respondents who vary in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class might be asked to complete a survey about television program preferences or attitudes toward the use of the Internet. The attitudes of males and females could then be compared, as should attitude based on age. In cross-sectional research, respondents are measured only once. This method is much less expensive as other developmental methods but does not allow the researcher to distinguish between the impact of age and the cohort effect. A research is also unable to identify individual change that happens as the participant is only measures one time. Different attitudes about the Internet, for example, might not be altered by a person’s biological age as much as their life experiences as members of a cohort.

In another example for cross-sectional research, a researcher might want to examine hide-and-seek behaviors in children to find out whether older children more often hide in unique locations (those in which another child in the same game has never hidden before) when compared to younger children. In this case, the researcher might observe 2, 4, and 6-year-old children as they play the game (the various age groups represent the “cross sections”). This research is cross-sectional because the researcher plans to examine the behavior of children of different ages within the same study at the same time.

| Cohort tracked in 2019 | Age |

| A | 2- year-olds |

| B | 6-year-olds |

| C | 8-year-olds |

Example of cross-sectional study tracking 3 different groups of children in the same time period. Based on chart: https://nobaproject.com/modules/research-methods-in-developmental-psychoogy

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background and measuring them repeatedly over a long period. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with them when they were younger. A problem with this type of research is that it is costly and subjects may drop out over time.

The same example of the hide-and-seek study, can also be run as a longitudinal. A researcher might conduct a longitudinal study to examine whether 2-year-olds develop into better hiders over time. To this end, a researcher might observe a group of 2-year-old children playing hide-and-seek with plans to observe them again when they are 4 years old – and again when they are 6-years old. This study is longitudinal because the researcher plans to study the same children as they age. Based on her data, the researcher might conclude that 2-year-olds develop more mature hiding abilities with age. Remember, researchers examine games, such as hide-and-seek, not because they are interested in the games themselves, but because they offer clues to how children think, feel and behave at various ages.

| Child “A” 2-years-old 2004 |

Child “A” 4-years-old 2006 |

Child “A” 6-years-old 2008 |

Child “A” 8-years-old 2010 |

Example of longitudinal study – tracking same group of children over time. Based on the chart: https://nobaproject.com/modules/research-methods-in-developmental-psychology

What would be the drawbacks of being in a longitudinal study? What would be the advantages and disadvantages? Can you imagine why some would continue, and others drop out of the project?

Cross-sequential research involves combining aspects of the previous two techniques; beginning with a cross-sectional sample and measuring them through time. Similar to longitudinal designs, cross-sequential research features participants who are followed over time; similar to cross-sectional designs, sequential work includes participants of different ages. This research design is also distinct from those that have been discussed previously in that children of different ages are enrolled into a study at various points in time to examine age-related changes, development within the same individuals as they age, and account for the possibility of cohort effects. This is the perfect model for looking at age, gender, social class, and ethnicity. However, the drawbacks include high costs and low rates of attrition.

Consider, once again, our example of hide-and-seek behaviors. In a study with a sequential design, a researcher might enroll three separate groups of children (Groups A, B, and C). Children in Group A would be enrolled when they are 2 years old and would be tested again when they are 4 and 6 years old (similar in design to the longitudinal study described previously). Children in Group B would be enrolled when they are 4 years old and would be tested again when they are 6 and 8 years old. Finally, children in Group C would be enrolled when they are 6 years old and would be tested again when they are 8 and 10 years old.

| 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | |

| Cohort A | Age 2 | Age 4 | Age 6 |

| Cohort B | — | Age 2 | Age 4 |

| Cohort C | — | — | Age 2 |

Example of cross-sectional study tracking different groups across time. Based on the chart: https://nobaproject.com/modules/research-methods-in-developmental-psychology

Conducting Ethical Research

One of the issues that all scientists must address concerns the ethics of their research. Research in psychology may cause some stress, harm, or inconvenience for the people who participate in that research. Psychologists may induce stress, anxiety, or negative moods in their participants, expose them too weak electrical shocks, or convince them to behave in ways that violate their moral standards. Additionally, researchers may sometimes use animals, potentially harming them in the process.

Decisions about whether research is ethical are made using established ethical codes developed by scientific organizations, such as the American Psychological Association, and federal governments. In the United States, the Department of Health and Human Services provides the guidelines for ethical standards in research. The following are the American Psychological Association code of ethics when using humans in research (APA, 2002).

No Harm: The most direct ethical concern of the scientist is to prevent harm to the research participants.

Informed Consent: Researchers must obtain informed consent, which explains as much as possible about the true nature of the study, particularly everything that might be expected to influence willingness to participate. Participants can withdraw their consent to participate at any point.

Infants and young children cannot verbally indicate their willingness to participate, much less understand the balance of potential risks and benefits. As such, researchers are often required to obtain written informed consent from the parent or legal guardian of the child participant. Further, this adult is almost always present as the study is conducted. Children are not asked to indicate whether they would like to be involved in a study until they are approximately 7 years old. Because infants and young children also cannot easily indicate if they would like to discontinue their participation in a study, researchers must be sensitive to changes in the state of the participant, such as determining whether a child is too tired or upset to continue, as well as to what the parent desires. In some cases, parents might want to discontinue their involvement in the research. As in adult studies, researchers must always strive to protect the rights and well- being of the minor participants and their parents when conducting developmental research.

Confidentiality: Researchers must also protect the privacy of the research participants’ responses by not using names or other information that could identify the participants.

Deception: Deception occurs whenever research participants are not completely and fully informed about the nature of the research project before participating in it. Deception may occur when the researcher tells the participants that a study is about one thing when in fact it is about something else, or when participants are not told about the hypothesis.

Debriefing: At the end of a study debriefing, which is a procedure designed to fully explain the purposes and procedures of the research and remove any harmful after-effects of participation, must occur.

Conclusion

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of changes that occur in human beings throughout their lives. This is a breadth course covering many aspects of human development. This field examines change and development across a broad range of topics, such as aspects of physical development (motor skills and other psycho-physiological processes); cognitive development (problem-solving, language acquisition); social and emotional development; and self- concept and identity formation. Lifespan development is influenced by context (SES, culture). Much of what is known concerning the lifespan has been information gathered through research. Chapter one covered the basics of research methods and ethics. In the next chapter, we will explore major developmental theories.

Chapter 1 Key Terms

| human development | experimental research method |

| culture | independent variable |

| ethnocentrism | dependent variable |

| cultural relativity | cross-sectional research |

| socioeconomic status (social class) | longitudinal research |

| ethnicity | cross-sequential research |

| cohort effect | case study |

| sampling bias | observation |

| confirmation bias | survey |

| variable | interview |

| scientific method | informed consent |

| research design | quantitative |

| sample | qualitative |

| population |