There is evidence suggesting that many workers lose their jobs not due to a lack of technical knowledge but because of difficulties working effectively with others (Cascio, in Berger, 2005). Success in the workplace requires more than job-specific skills; it depends on a combination of cognitive abilities and “soft” skills. Colleges play a critical role in fostering these qualities, helping students develop verbal, quantitative, and critical thinking skills that are transferable across careers and life contexts. Beyond academics, higher education also provides opportunities to refine soft skills such as teamwork, communication, time management, leadership, and adaptability. These skills are essential for navigating diverse work environments and meeting employers’ expectations. While these abilities can be developed outside of formal education, college offers a structured setting where they are consistently practiced and reinforced. Employers increasingly seek candidates who not only hold degrees but also demonstrate these interpersonal and cognitive competencies, which are crucial for long-term success in the workplace.

Chapter 8: Emerging Adulthood

Objectives:

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to…

- Define emerging adulthood.

- Identify the five features that distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages.

- Describe the variations in emerging adulthood in countries around the world.

- Explain dialectical thought.

- Describe some current concerns in education in today’s colleges.

- Discuss sexual responses

- Define NEETs.

- Describe risky behavior in emerging adulthood.

- Summarize Levinson’s theory of adult transitions.

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Introduction

Think for a moment about the lives of your grandparents and great-grandparents when they were in their twenties. How do their lives at that age compare to your life? If they were like most other people of their time, their lives were quite different from yours. What happened to change the twenties so much between their time and our own? And how should we understand the 18–25 age period today?

Think for a moment about the lives of your grandparents and great-grandparents when they were in their twenties. How do their lives at that age compare to your life? If they were like most other people of their time, their lives were quite different from yours. What happened to change the twenties so much between their time and our own? And how should we understand the 18–25 age period today?

In this chapter, we are introducing a relatively new stage of life, emerging adulthood. We have seen the age span between adolescence and adulthood expanded due to changes in society.

Emerging Adulthood (Ob 1)

The theory of emerging adulthood proposes that a new life stage has arisen between adolescence and young adulthood over the past half-century in industrialized countries. Fifty years ago, most young people in these countries had entered stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. Relatively few people pursued education or training beyond secondary school, and, consequently, most young men were full-time workers by the end of their teens. Relatively few women worked in occupations outside the home, and the median marriage age for women in the United States and in most other industrialized countries in 1960 was around 20 (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Douglass, 2005). The median marriage age for men was around 22, and married couples usually had their first child about one year after their wedding day. All told, for most young people half a century ago, their teenage adolescence led quickly and directly to stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. These roles would form the structure of their adult lives for decades to come.

Now, all that has changed. In 2022, 62% of high school graduates enrolled in college which is a decline from 70% in 2016 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024). The early twenties are not a time of entering stable adult work but a time of immense job instability: In the United States, the average number of job changes from ages 20 to 29 is seven. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is now 28.6 for women and 30.5 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2022). Consequently, a new stage of the life span, emerging adulthood, has been created, lasting from the late teens through the mid-twenties, roughly ages 18 to 25.

In industrialized countries, young people just out of high school and into their 20’s are spending more time experimenting with potential directions for their lives. This new way of transitioning into adulthood is different enough from generations past that it is considered a new developmental phase – emerging adulthood.

Emerging Adulthood Defined (Ob 1, Ob 2)

Emerging adulthood is the period between the late teens and early twenties; ages 18-25, although some researchers have included up to age 29 in the definition (Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood, 2016). Jeffrey Arnett (2000) argues that emerging adulthood is neither adolescence nor is it young adulthood. Individuals in this age period have left behind the relative dependency of childhood and adolescence, but have not yet taken on the responsibilities of adulthood. “Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future is decided for certain when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities are greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course” (Arnett, 2000, p. 469).

Arnett has identified five characteristics of emerging adulthood that distinguishes it from adolescence and young adulthood (Arnett, 2006).

- It is the age of identity exploration. In 1950, Erik Erikson proposed that it was during adolescence that humans wrestled with the question of identity. Yet, even Erikson (1968) commented on a trend during the 20th century of a “prolonged adolescence” in industrialized societies. Today, most identity development occurs during the late teens and early twenties rather than adolescence. It is during emerging adulthood that people are exploring their career choices and ideas about intimate relationships, setting the foundation for adulthood. Emerging adulthood is an extended period of time for exploring who the young adult is and what he/she wants out of work, love, and life. Part of that exploration is attending postsecondary (tertiary) education to expand more pathways for work. Tertiary education includes community colleges, universities, and trade schools.

- Arnett also described this time period as the age of instability (Arnett, 2000; Arnett, 2006). Exploration generates uncertainty and instability. Emerging adults change jobs, relationships, and residences more frequently than other age groups. Rates of residential change in American society are much higher at ages 18 to 29 than at any other period of life (Arnett, 2004). This reflects the explorations going on in emerging adults’ lives. Some move out of their parents’ household for the first time in their late teens to attend a residential college, whereas others move out simply to be independent (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). They may move again when they drop out of college or when they graduate. They may move to cohabit with a romantic partner and then move out when the relationship ends. Some move to another part of the country or the world to study or work. For nearly half of American emerging adults, residential change includes moving back in with their parents at least once (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). In some countries, such as in southern Europe, emerging adults remain in their parents’ home rather than move out; nevertheless, they may still experience instability in education, work, and love relationships (Douglass, 2005, 2007).

- This is also the age of self-focus. Being self-focused is not the same as being “self-centered.” Adolescents are more self-centered than emerging adults. Arnett reports that in his research, he found emerging adults to be very considerate of the feelings of others, especially their parents. They now begin to see their parents as people not just parents, something most adolescents fail to do (Arnett, 2006). Nonetheless, emerging adults focus more on themselves, as they realize that they have few obligations to others and that this is the time where they can do what they want with their life. Most American emerging adults move out of their parents’ home at age 18 or 19 and do not marry or have their first child until at least their late twenties (Arnett, 2004). Even in countries where emerging adults remain in their parents’ home through their early twenties, as in southern Europe and in Asian countries such as Japan, they establish a more independent lifestyle than they had as adolescents (Rosenberger, 2007). Emerging adulthood is a time between adolescents’ reliance on parents and adults’ long-term commitments in love and work, and during these years, emerging adults focus on themselves as they develop the knowledge, skills, and self-understanding they will need for adult life. In the course of emerging adulthood, they learn to make independent decisions about everything from what to have for dinner to whether or not to get married.

- This is also the age of feeling in-between. When asked if they feel like adults, more 18 to 25-year-olds answer “yes and no” than do teens or adults over the age of 25 (Arnett, 2001). Most emerging adults have gone through the changes of puberty, are typically no longer in high school, and many have also moved out of their parents’ home. Thus, they no longer feel as dependent as they did as teenagers. Yet, they may still be financially dependent on their parents to some degree, and they have not completely attained some of the indicators of adulthood, such as finishing their education, obtaining a good full-time job, being in a committed relationship, or being responsible for others. It is not surprising that Arnett found that 60% of 18 to 25-year-olds felt that in some ways they were adults, but in some ways, they were not (Arnett, 2001,). It is only when people reach their late twenties and early thirties that a clear majority feels adult. Most emerging adults have the subjective feeling of being in a transitional period of life, on the way to adulthood but not there yet. This “in-between” feeling in emerging adulthood has been found in a wide range of countries, including Argentina (Facio & Micocci, 2003), Austria (Sirsch et al., 2009), Israel (Mayseless & Scharf, 2003), the Czech Republic (Macek et al., 2007), and China (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

- Emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities. It tends to be an age of high hopes and great expectations, in part because few of their dreams have been tested in the fires of real life. In one national survey of 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States, nearly all—89%—agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life” (Arnett & Schwab, 2012). This optimism in emerging adulthood has been found in other countries as well (Nelson & Chen, 2007). Arnett (2000, 2006) suggests that this optimism is because these dreams have yet to be tested. For example, it is easier to believe that you will eventually find your soulmate when you have yet to have had a serious relationship. It may also be a chance to change directions, for those whose lives up to this point have been difficult. The experiences of children and teens are influenced by the choices and decisions of their parents. If the parents are dysfunctional, there is little a child can do about it. In emerging adulthood, people can move out and move on. They have the chance to transform their lives and move away from unhealthy environments. Even those whose lives were happier and more fulfilling as children, now have the opportunity in emerging adulthood to become independent and make decisions about the direction they would like their life to take.

The years of emerging adulthood are often times of identity exploration through work, fashion, music, education, and other venues.

To what extent do you think these have changed in the last several years? The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally? How might these tasks be different across cultures?

To what extent do you think these have changed in the last several years? The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally? How might these tasks be different across cultures?

SES and Cultural Influences of EA

Socioeconomic status (SES) and cultural influences significantly shape the experience of emerging adulthood, creating variability in how young people navigate this developmental stage. Individuals from lower SES backgrounds often face economic instability, limiting opportunities for identity exploration and delaying traditional milestones such as pursuing higher education, independent living, and career development. Financial constraints may force young adults to prioritize immediate financial stability over personal aspirations, reducing optimism and opportunities for exploration (Arnett, 2016; Landberg et al., 2019). In contrast, higher SES individuals may have greater access to resources that facilitate identity exploration and achievement. Cultural values also play a central role; in individualistic societies, emerging adulthood often emphasizes independence and self-discovery, whereas collectivistic cultures prioritize interdependence and familial obligations. However, globalization is blurring these distinctions, with traditionally collectivistic cultures adopting more individualistic attitudes (Sugimura, 2020). For example, young adults in Japan increasingly prioritize personal goals like career satisfaction over traditional family roles (Arnett et al., 2014). Additionally, cultural discrimination can hinder identity exploration for marginalized groups. For instance, Black emerging adults often face systemic barriers that disrupt career and self-exploration (Hope et al., 2015). Immigrants may experience tension between their heritage culture and the dominant culture of their new country, further complicating identity formation (Quan et al., 2022). Together, SES and cultural factors highlight the diversity of paths through emerging adulthood and the need for supportive systems tailored to these varied experiences.

International Variations in EA (Ob 3)

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

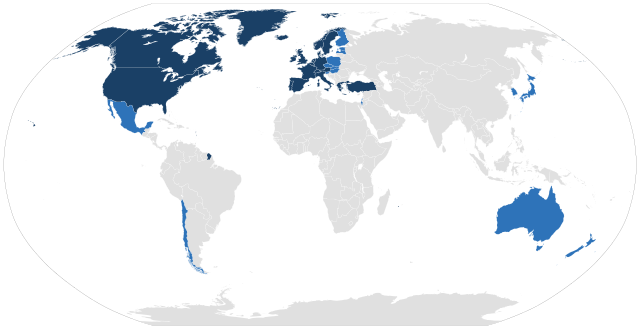

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the non-industrialized countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the industrialized countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called industrialized countries) is 1.38 billion, about 17% of the total world population (UNDP, 2024). The rest of the human population resides in non-industrialized countries, which have much lower median incomes; much lower median educational attainment; and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in non-industrialized countries.

EA in OECD Countries: The Advantages of Affluence

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UNdata, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world—in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in industrialized countries such as Japan and South Korea are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood—for example, free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations. Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson, Badger, & Wu, 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Another notable contrast between Western and Asian emerging adults is in their sexuality. In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties, when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).

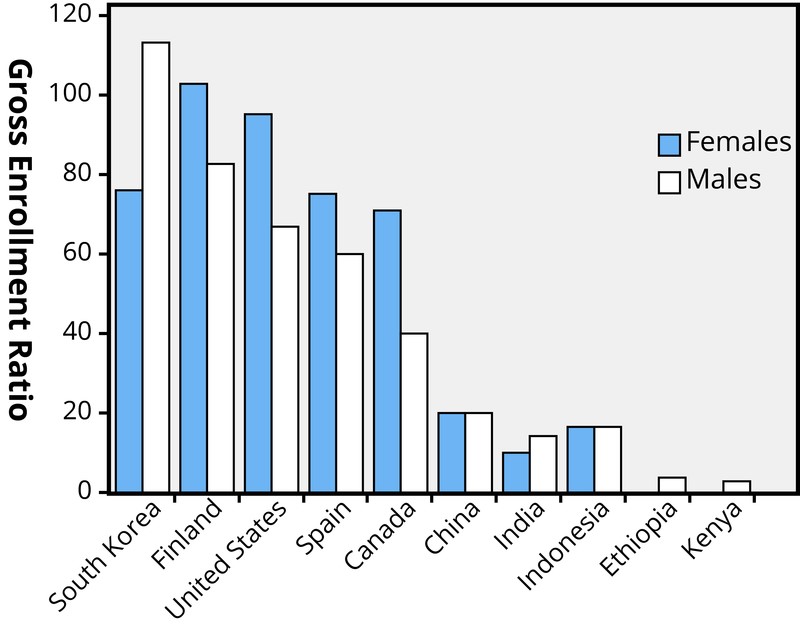

EA in Developing Countries: Low but Rising

Emerging adulthood is well established as a normative life stage in the industrialized countries described thus far, but it is still growing in non-industrialized countries. Demographically, in non-industrialized countries as in OECD countries, the median ages for entering marriage and parenthood have been rising in recent decades, and an increasing proportion of young people have obtained post-secondary education. Nevertheless, currently it is only a minority of young people in non-industrialized countries who experience anything resembling emerging adulthood. The majority of the population still marries around age 20 and has long finished education by the late teens. As you can see in the figure below, rates of enrollment in tertiary education are much lower in non-industrialized countries (represented by the five countries on the right) than in OECD countries (represented by the five countries on the left).

For young people in non-industrialized countries, emerging adulthood exists only for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class, whereas the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work at an early age and also begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. What Saraswathi and Larson (2002) observed about adolescence applies to emerging adulthood as well: “In many ways, the lives of middle-class youth in India, South East Asia, and Europe have more in common with each other than they do with those of poor youth in their own countries.” However, as globalization proceeds, and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood is likely to be normative worldwide.

Physical Development

Physiological Peak (Ob 4)

If you are in your early twenties, you are probably at the peak of your physiological development. Your body has completed its growth, though your brain is still developing (as explained in the adolescence chapter). Our early twenties are considered a physiological peak as physically, you are in the “prime of your life” as your reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity are operating at their best. As will be discussed in later chapters, these systems will start a slow, gradual decline so that by the time you reach your mid to late 30s, you will begin to notice signs of aging.

The good news is that healthy habits established early influence later well-being, especially cardiovascular health (Liu et al., 2012). For example, a healthy diet and a physically active lifestyle can help to protect cardiovascular health, even if a person has a genetic predisposition toward heart disease (U.S. Preventative Services Task Force, 2020). Physical activity builds and maintains muscle, bone, and joint health and improves strength. Being moderately active can also help maintain the health and functioning of the heart and lungs, counteract the negative effects of stress, and reduce blood pressure (Chen et al., 2020).

Here is a recap for some of the physiological peaks (more discussion in the next chapter):

Skin. The level of collagen, a substance that helps keep skin firm and elastic, peaks at 25 and slowly declines afterwards (Reilly & Lozano, 2021).

Lungs: Your lungs mature by the time you are about 20-25 years old. The maximum amount of air adult lungs can hold, total lung capacity, is about 6 liters (that is like three large soda bottles) (American Lung Association, n.d.).There are several different ways measures to examine lung capacity (spirometry). One is having you exhale with force. The amount of air you can exhale with force in 1 second is called forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1). FEV1 declines 1 to 2 percent per year after about the age of 25, which may not sound like much but adds up.

Bones. Bones stop growing between the ages of 17 and 25 when the epiphyses, the ends of long bones like the ones in our arms and legs, fuse together. The collarbone is the last bone to mature, around the age of 25 (Hughes et al, 2020; Olivares et al., 2020). There’s also an increase in bone mineral density (Hochberg & Konner, 2020; Lantz et al., 2008).

Muscle: Muscle strength peaks just prior to our thirties (Gabbard, 2014). As we age we lose muscle mass, strength, and function (sarcopenia). In sports we see baseball players hit their peak between 27 and 30, athletic throwing at 27 years, and swimmers peak around 20 (Allen & Hopkins, 2015). For setting world records in a given athletic discipline, the mean age is 26 for men and 25 for women (Statszone, 2016). Connected to muscle strength and lung capacity, in aerobic events, performance usually peaks in the mid-twenties, as gains from training, improved mechanical skills and competitive experiences are negated by decreases in maximal oxygen intake and muscle flexibility (Shepard, 1998).

Joints. The quality and amount of synovial fluid, the lubricant keeping joints healthy, starts to show some minimal decline as early as age 28, which can lead to increased stiffness (Temple-Wong et al., 2016). For individuals who have had an injury, such as athletes or from an accident, post-traumatic arthritis osteoarthritis may also occur (Punzi et al., 2016).

Endocrine system. Testosterone peaks sometime between the late teens and mid 20s and then remains stable until middle age (Hochberg & Konner, 2020; Hull et al., 2011). Fasting glucose levels drop in adolescence and the early parts of emerging adulthood, starting to rise after age 25 (Hammel et al., 2022); similarly, insulin resistance increases after age 20 (Zhong et al., 2019).

Cognitive motor skills: The present study investigates age-related changes in cognitive motor performance through adolescence and adulthood in a complex real world task, the real-time strategy video game StarCraft 2. In this paper we analyze the influence of age on performance using a dataset of 3,305 players, aged 16-44, collected by Thompson et al. (2014). Using a piecewise regression analysis, we find that age-related slowing of within-game, self-initiated response times begins at 24 years of age. We find no evidence for the common belief expertise should attenuate domain specific cognitive decline. Domain-specific response time declines appear to persist regardless of skill level.

Cognitive Development

Piaget believed that formal operational thought was the last stage in our cognitive development, but is this actually the case? Do you currently have the same cognitive skills and reason the same way you did when you were 14? Put another way, do you currently have the same problems and life circumstances you had when you were 14?

Though adolescents in the formal operational stage can easily think hypothetically, they lack experience with the world and are often unable to consider as many possibilities as adults can. Adults are better able to predict likely outcomes or consequences, combining abstract thought and logic with intuition and life experience. This ability to think of potential outcomes is one of the hallmarks of post-formal thought, and it extends Piaget’s ideas about formal operations to the unique skills and abilities developed during emerging adulthood and adulthood.

Dialectical Thought (Ob 4)

Post-adolescence, individuals may become more flexible and balanced. Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the adult evaluates reality. Adolescents tend to think in dichotomies; ideas are true or false; good or bad; right or wrong and there is no middle ground. However, with experience, the adult comes to recognize that there are some right and some wrong in each position, some good or some bad in a policy or approach, some truth and some falsity in a particular idea. This ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong. So, for example, parents who were considered angels or devils by the adolescent eventually become just people with strengths and weaknesses, endearing qualities and faults to the adult.

Solving adult problems requires integrating multiple sources of information and engaging in reflective thought, a process that involves actively evaluating information and beliefs using evidence and past experiences. Reflective thought enables individuals to question facts, draw inferences, and connect diverse types of information, fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019). This cognitive ability typically emerges between the ages of 20 and 25, coinciding with brain myelination, which enhances neural efficiency and connectivity. Reflective thought is essential for navigating the complexities of emerging adulthood, where individuals face challenges such as career decisions, relationship dynamics, and personal identity formation.

Education and Employment

Educational Concerns (Ob 5)

Higher education offers significant personal, professional, and societal benefits during emerging adulthood (ages 18–25), though the experience varies widely based on individual circumstances. For many first-generation college students, the transition to college can be a culture shock as they navigate unfamiliar social networks and institutional systems. Despite these challenges, higher education provides a structured environment for developing critical cognitive abilities such as verbal, quantitative, and analytical skills, along with transferable “soft” skills like communication, time management, leadership, and teamwork. These competencies not only prepare students for the workforce but also enhance their ability to adapt to complex life challenges.

Socioeconomic status (SES) influences how and when students pursue higher education. Students from lower SES backgrounds are more likely to attend community colleges part-time while balancing work or family responsibilities, which can delay or interrupt degree completion. In contrast, students from higher SES families are more likely to enroll full-time at four-year institutions and complete their degrees by age 25. Working part-time during college is associated with better outcomes, such as increased campus engagement and skill development, but working more than 20 hours per week is linked to lower GPAs and reduced graduation rates (Pike et al., 2008).

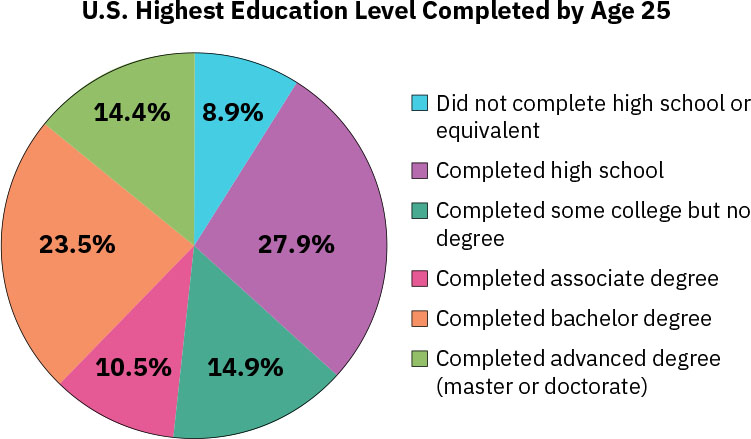

In 2021, the high school completion rate in the United States for people ages 25 and older rose to 91.1% from 87% in 2011. The percentage of the population age 25 and older with associate degrees rose to 10.5%, up 1% from 2011. Between 2011 and 2021, the percentage of people age 25 and older who had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher increased by 7.5% from 30.4% to 37.9%. From 2011 to 2021, the number of people ages 25 and over whose highest degree was a master’s degree rose to 24.1 million, and the number of doctoral degree holders rose to 4.7 million, a 50.2% and 54.5% increase, respectively. About 14.3% of adults had an advanced degree in 2021, up 3.4% from 2011 (US Census Bureau, 2021).

The long-term benefits of higher education are substantial. College graduates enjoy higher earnings, better job opportunities, and greater job satisfaction when their careers align with their interests and college majors (Wolniak & Engberg, 2019). Experiences like internships or study abroad programs during college are associated with increased workplace success and earnings (Wolniak & Pascarella, 2005). While some students switch majors—30% do so within three years—this can improve graduation rates when supported by career resources (National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). In 2018, the average (median) earnings for Americans 25 and older with only a high school education was $44,356, compared with $74,464 for those with a bachelor’s degree, compared with $86,372 for those with a master’s degree. Average earnings vary by gender, race, and geographical location in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Beyond financial gains, higher education fosters personal growth by encouraging exploration of passions and building a foundation for lifelong learning. For those who choose this path, the benefits of college extend far beyond earning a degree—they include shaping identity, building resilience, and preparing for meaningful contributions to society.

Quality education is more than a credential. Being able to communicate and work well with others is crucial for success. These are considered soft skills. In an article referring to information from the National Association of Colleges and Employers’ 2018 Job Outlook Survey, Bauer-Wolf (2018) explains that employers perceive gaps in students’ competencies but many graduating college seniors are overly confident. The biggest difference was in perceived professionalism and work ethic (only 43% of employers thought that students are competent in this area compared to 90 percent of the students). Similar differences were also found in terms of oral communication, written communication, and critical thinking skills (Bauer-Wolf). Only in terms of digital technology skills were more employers confident about students’ competencies than were the students (66% compared to 60%). While students cannot learn every single skill or fact that they may need to know, they can learn how to learn, think, research, and communicate well so that they are prepared to continually learn new things and adapt effectively in their careers and lives since the economy, technology, and global markets will continue to evolve (Henseler, 2017).

What can societies do to enhance the likelihood that emerging adults will make a successful transition to adulthood? One important step would be to expand the opportunities for obtaining tertiary education. The tertiary education systems of OECD countries were constructed at a time when the economy was much different, and they have not expanded at the rate needed to serve all the emerging adults who need such education. Furthermore, in some countries, such as the United States, the cost of tertiary education has risen steeply and is often unaffordable to many young people. In developing countries, tertiary education systems are even smaller and less able to accommodate their emerging adults. Across the world, societies would be wise to strive to make it possible for every emerging adult to receive tertiary education, free of charge. There could be no better investment for preparing young people for the economy of the future.

NEETs (Ob 7)

NEET stands for ‘Not in Employment, Education or Training’. Around the world, teens and young adults were some of the hardest hit by the economic downturn in recent years (Desilver, 2016). In 2023, about 16% of young adults ages 18 to 24 in the U.S. were considered NEETs, and globally 21.7% (Rodgers et al, 2024; ILO, 2024). Young people in education include those attending part-time or full-time education but exclude those in non-formal education and in educational activities of very short duration. Employment covers all those who have been in paid work for at least one hour in the reference week being asked about or were temporarily absent from work during that time (but still employed). NEETs can be either unemployed or inactive and not involved in education or training. Young people who are neither in employment nor in education or training are at risk of becoming socially excluded – individuals with income below the poverty line and lacking the skills to improve their economic situation.

Causes of NEET:

- The main cause of NEET is high youth unemployment. This can be caused by a variety of factors, such as:

- unskilled and no relevant qualifications

- Geographical factors, such as high rates of local unemployment and geographical unemployment

- Poor expectations fostered by lack of role models and high unemployment

- Recession as levels of NEET increase during recessions.

- Lack of available education and training programs.

- Education and training programs that are not suitable.

- Unwillingness or poor information about available training and education programs

Young people with an early onset of mental health and behavioral problems are at risk of failing to make the transition from school to employment or becoming a NEET. Interestingly, after tracking over 4,000 Swiss males in their early 20s, the research showed that when comparing NEETs and non-NEETs, NEETs had higher usage of substance use (smoking, cannabis use, and hazardous cannabis use) and more depressive symptoms (Baggio et al., 2015). In their study, longitudinal associations showed that previous mental health, cannabis use, and daily smoking increased the likelihood of being NEET. Another Dutch study tracking individuals 11-19 years old found that young adults with high-stable trajectories of mental health problems were more at risk to be NEETs (Veldman et al., 2015). Further, a study tracking adolescents in Victoria, Australia found that frequent adolescent cannabis use, reporting repeated disruptive, or reporting persistent common mental disorders in adolescence were predictors of young adults not employed or pursuing postsecondary education (Rodwell et al., 2018). The risk for NEETs are more than impacting their economic future, as NEETs face mental health challenges, substance use, and suicide attempts (Scott et al., 2013).

While the number of young people who are NEETs has declined, there is a concern that “without assistance, economically inactive young people won’t gain critical job skills and will never fully integrate into the wider economy or achieve their full earning potential” (Desilver, 2016, para. 3). In Europe, where the rates of NEETs are persistently high, there is also concern that having such large numbers of young adults with little opportunity may increase the chances of social unrest. More women than men find themselves unemployed and not in school. Additionally, most NEETs have a high school or less education, and Asians are less likely to be NEETs than any other ethnic group.

The rate of NEETs varies in European nations, with higher rates found in nations that have been the hardest hit by economic recessions and government austerity measures. For example, more than 25% of those 15-29 (European data use a lower age group: 15 rather than 16) in Greece and Italy are unemployed and not seeking or receiving further education. In contrast, countries less affected by an economic downturn, such as Denmark, had much lower rates (7.3%).

While NEETs struggle with jobs that pay enough to live on and other possible challenges, Levy and Murnane (2012) identified six basic skills NEETs need as job skills to succeed in the workplace, referred to as new basic skills:

- read at 9th grade level or higher

- solve math skills at 9th grade level or higher

- solve semi-structured problems

- written and oral communication

- use of word processor and other tasks on a computer

- collaborate in diverse groups

Sexuality (Ob 6)

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest themselves in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual-response cycle and the basic biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals that are expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality also impacts and is impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

The experience and expression of sexuality are unique to everyone. The peak of sexual activity generally occurs between the ages of 18 and 24, though the number of adults in this age group who were sexually active decreased somewhat between the years 2000 and 2018, especially men (Ueda et al., 2020). Becoming sexually active is a common part of growing up, although it’s not a mandatory element (i.e., people who are asexual or who abstain from sexual activity for religious or other reasons aren’t somehow “defective”). Sexual activity is also, for many people, a healthy and enjoyable aspect of their lives. However, sometimes sexual activity has unwanted health consequences, such as sexually transmitted infections or unintended pregnancy.

Sexual Response Cycle: Sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. This motivation is determined by biological, psychological, and social factors. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability to engage in sexual behaviors. However, sex hormones do not directly regulate the ability to copulate in primates (including humans); rather, they are only one influence on the motivation to engage in sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as work and family also have an impact, as do internal psychological factors like personality and stress. Sex drive may also be affected by hormones, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle stress, pregnancy, and relationship issues. The sexual response cycle is a model that describes the physiological responses that take place during sexual activity. According to Kinsey et al. (1948), the sexual response cycle consists of four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. The excitement phase is the phase in which the intrinsic (inner) motivation to pursue sex arises. The plateau phase is the period of sexual excitement with increased heart rate and circulation that sets the stage for orgasm. Orgasm is the release of tension, and the resolution period is the unaroused state before the cycle begins again.

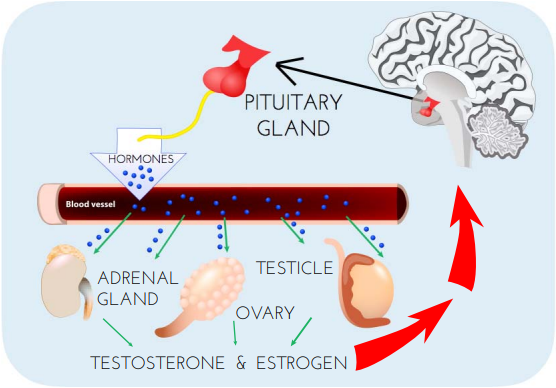

The Brain and Sex: The brain is the structure that translates the nerve impulses from the skin into pleasurable sensations. It controls the nerves and muscles used during sexual behavior. The brain regulates the release of hormones, which are believed to be the physiological origin of sexual desire. The cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain that allows for thinking and reasoning, is believed to be the origin of sexual thoughts and fantasies. Beneath the cortex is the limbic system, which consists of the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and septal area. These structures are where emotions and feelings are believed to originate and are important for sexual behavior. The hypothalamus is the most important part of the brain for sexual functioning. This is the small area at the base of the brain consisting of several groups of nerve-cell bodies that receives input from the limbic system. Studies with lab animals have shown that destruction of certain areas of the hypothalamus causes complete elimination of sexual behavior. One of the reasons for the importance of the hypothalamus is that it controls the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control the other glands of the body.

Hormones: Several important sexual hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin, also known as the hormone of love, is released during sexual intercourse when an orgasm is achieved. (Oxytocin is also released in females when they give birth or are breastfeeding; it is believed that oxytocin is involved with maintaining close relationships.) For reproduction, the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is responsible for ovulation by triggering egg maturity; it also stimulates sperm production in males. For females, the luteinizing hormone (LH) triggers the release of a mature egg in females during the process of ovulation. In males, testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation. Vasopressin is involved in the male arousal phase, and the increase of vasopressin during erectile response may be directly associated with increased motivation to engage in sexual behavior. The relationship between hormones and female sexual motivation is not as well understood, largely due to the overemphasis on male sexuality in Western research. Estrogen and progesterone typically regulate motivation to engage in sexual behavior for females, with estrogen increasing motivation and progesterone decreasing it. The levels of these hormones rise and fall throughout a woman’s menstrual cycle. Research suggests that testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships.

Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular sex or gender. It is a personal quality that inclines people to feel romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of a given sex or gender. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) (2016), sexual orientation also refers to a person’s sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions.

Sexual Orientation on a Continuum: Sexuality researcher Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey et al. (1948) created a seven-point rating scale that ranged from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Research done over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016).

However, sexual orientation now can be defined in many ways. Heterosexuality, which is often referred to as being straight, is attraction to individuals of the opposite sex/gender, while homosexuality, being gay or lesbian, is attraction to individuals of one’s own sex/gender. Bisexuality was a term traditionally used to refer to attraction to individuals of either male or female sex, but it has recently been used in nonbinary models of sex and gender (i.e., models that do not assume there are only two sexes or two genders) to refer to attraction to any sex or gender. Alternative terms such as pansexuality and polysexuality have also been developed, referring to attraction to all sexes/genders and attraction to multiple sexes/genders, respectively (Carroll, 2016). Asexuality refers to having no sexual attraction to any sex/gender. According to Bogaert (2015) about one percent of the population is asexual. Being asexual is not due to any physical problems, and the lack of interest in sex does not cause the individual any distress. Asexuality is being researched as a distinct sexual orientation.

Figuring out one’s sexual orientation and gender identity during adolescence is a complex and individualized process influenced by cultural, societal, and personal factors. In cultures where LGBTQ+ individuals face stigma or criminalization, coming out may pose significant risks, leading some to delay disclosure until later in life or avoid it altogether (Rosati et al., 2020). Even in LGBTQ+ supportive countries, acceptance varies widely among communities and individuals. Coming out is not a singular event but involves multiple stages, such as recognizing attraction, identifying with a specific orientation, forming relationships, and disclosing to others. These stages often occur in a consistent sequence but vary in timing based on factors like gender, sexual orientation, and generational differences. For example, men and those identifying as gay or lesbian tend to complete these tasks earlier than women or bisexual individuals. Additionally, younger cohorts report earlier disclosure and relationship milestones compared to older generations, reflecting shifting societal attitudes toward non-heterosexual identities (Martos et al., 2015; van Bergen et al., 2021).

Sexual harassment and sexual violence

Sexual harassment and sexual violence are serious issues that can profoundly impact adolescents. Sexual violence encompasses any non-consensual sexual activity, including assault, abuse, exploitation, and stalking, with force taking verbal, physical, or emotional forms (National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 2010). Sexual harassment refers to unwanted sexual attention—verbal or physical—that disrupts an individual’s ability to engage in daily activities. It often involves power imbalances but can also occur among peers (Barber, 1996). Acts like rape or unwanted touching fall under both harassment and sexual assault, with consent requiring explicit agreement; silence or inability to refuse due to fear, intoxication, or unconsciousness does not constitute consent. Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to these experiences in both in-person and online contexts. For example, sexting and the non-consensual sharing of explicit images are increasingly common forms of harassment, often leading to anxiety, depression, and long-term emotional harm (Patchin & Hinduja, 2020). Addressing these issues requires comprehensive education on consent and healthy relationships, as well as supportive interventions to protect teens from harm and promote respectful interactions.

Gender

For many adults, the drive to adhere to masculine and feminine gender roles, or the societal expectations associated with being male or female, continues throughout life. In American culture, masculine roles have traditionally been associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles have traditionally been associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination. Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics, while women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as childcare, healthcare, and social work. These occupational roles are examples of stereotypical American male and female behavior, derived not from biology or genetics, but from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to these roles may demonstrate fulfillment of social expectations, however, not necessarily personal preferences (Diamond, 2002). Society is challenging the long-standing gender binary; that is, categorizing humans as only female and male, has been undermined by current psychological research (Hyde et al., 2019).

The term gender now encompasses a wide range of possible identities, including cisgender, transgender, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, bigender, pangender, ambigender, nongendered, intergender, and Two-spirit which is a modern umbrella term used by some indigenous North Americans to describe gender-variant individuals in their communities (Carroll, 2016). Hyde et al. (2019) advocates for a conception of gender that stresses multiplicity and diversity and uses multiple categories that are not mutually exclusive.

Emerging adulthood is a critical period for exploring and solidifying gender identity, as individuals gain greater independence and exposure to diverse perspectives. While many continue to navigate societal expectations tied to traditional masculine and feminine roles, others challenge these norms, embracing a broader spectrum of gender identities, including transgender, nonbinary, and genderqueer (Hyde et al., 2019). Gender identity development during this stage often involves self-exploration, meaning-making, and integration of one’s internal sense of self with external expressions such as clothing, pronouns, and social roles (Waagen, 2022; Kuper et al., 2018). Supportive environments—such as affirming families, peers, or educational institutions—can foster this exploration, while unsupportive or discriminatory settings may hinder it (Fiani & Han, 2019).

The transgender children, discussed in chapter 5 may, when they become an adult, alter their bodies through medical interventions, such as surgery and hormonal therapy, so that their physical being is better aligned with gender identity. However, not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies or physically transition. Many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as a different gender, often by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to a certain gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to the opposite gender, such as transvestites, drag kings, and drag queens, do not necessarily identify as transgender (though some do). People often confuse the term transvestite, which is the practice of dressing and acting in a style or manner traditionally associated with another sex (APA, 2013) with transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and not necessarily an expression about one’s gender identity.

Gender Minority Discrimination: Gender minority individuals face unique challenges during emerging adulthood. Transgender and nonbinary emerging adults frequently experience stigma, rejection, and discrimination in areas like housing, healthcare, and employment, which contribute to mental health disparities such as depression and anxiety (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Borgogna et al., 2019). Transgender individuals of color face additional financial, social, and interpersonal challenges, in comparison to the transgender community as a whole, as a result of structural racism. Black transgender people reported the highest level of discrimination among all transgender individuals of color. As members of several intersecting minority groups, transgender people of color, and transgender women of color in particular, are especially vulnerable to employment discrimination, poor health outcomes, harassment, and violence. Consequently, they face even greater obstacles than white transgender individuals and cisgender members of their own race.

Belongingness has been identified as a protective factor that mitigates the psychological impacts of rejection and victimization (Grossman et al., 2016). Belongingness, or the sense of being connected and valued within a group, is a critical protective factor for mental health during emerging adulthood. It mitigates the psychological impacts of rejection, victimization, and social isolation by fostering resilience and emotional well-being (Grossman et al., 2016; Baumeister & Leary, 1995). For transgender and gender-expansive emerging adults, belongingness reduces the negative effects of gender minority stressors, such as discrimination and social rejection, on mental health outcomes (PubMed, 2023). Conversely, thwarted belongingness—when individuals feel excluded or disconnected—amplifies the risks of depression and psychological distress (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Gerber & Wheeler, 2009). Positive social connections and inclusive environments, such as supportive peer groups or campus initiatives promoting inclusion, can help strengthen belongingness and reduce feelings of rejection (Walton & Cohen, 2011; Malone et al., 2012).

A significant contributing factor to risky behavior is alcohol. Binge drinking on college campuses has received considerable media and public attention. The NIAAA defines binge drinking when blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL. Furthermore, according to the NIAAA (2015) “Binge drinking poses serious health and safety risks, including car crashes, drunk-driving arrests, sexual assaults, and injuries. Over the long term, frequent binge drinking can damage the liver and other organs,” (p. 1). This typically occurs after four drinks for women and five drinks for men in approximately two hours. Binge drinking can lead to dangerous behaviors like reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters.

Alcohol and College Students: Results from the 2022 survey demonstrate the amount of alcohol consumed by college students (NIAAA, 2022). Specifically, 49% of full-time college students’ ages 18–22 drank alcohol in the past month compared with 51.5%, with 28.9% engaging in binge drinking. Binge drinking was defined as consuming five drinks or more on one occasion for males and four drinks or more for females. However, some college students drink at least twice that amount, a behavior that is often called high-intensity drinking.

The consequences for college drinking are staggering, and the NIAAA (2022) estimates that each year the following occur:

- 1,519 college students between the ages of 18 and 24 die from alcohol-related unintentional injuries, including motor vehicle crashes.

- 696,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 are assaulted by another student who has been drinking.

- Roughly 14% of college students meet the criteria for an Alcohol Use Disorder.

- About 1 in 4 college students report academic consequences from drinking, including missing class, falling behind in class, doing poorly on exams or papers, and receiving lower grades overall.

- 97,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 report experiencing alcohol-related sexual assault or date rape.

Non-Alcohol Substance Use: The most prevalent substances used by young adults ages 19 to 30 in 2021 are listed in the table below (Patrick et al., 2022). In 2021, marijuana use among young adults reached the highest levels ever recorded since the indices were first available in 1988. An index of non-medical use of any drugs other than marijuana includes hallucinogens (including LSD), cocaine, amphetamines, sedatives (barbiturates), tranquilizers, and narcotics (including heroin).

Table. Usage of various drugs reported for individuals ages 19-30 (2021)

| Past 12 months | Past 30 days | |

| Alcohol | 81.8% | 66.3% |

| Marijuana (any mode) | 42.6% | 28.5% |

| Vaping Nicotine | 21.8% | 16.1% |

| Vaping Marijuana | 18.7% | 12.4% |

| Cigarettes | 18.6% | 9.0% |

| Other Drugs | 18.3% | 7.5% |

Unsafe sexual encounters: Drug and alcohol use increases the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Lastly, as previously discussed, drugs and alcohol ingested during pregnancy have a teratogenic effect on the developing embryo and fetus.

The role alcohol plays in predicting acquaintance rape on college campuses is concerning. In the majority of cases of rape, the victim knows the rapist. Being intoxicated increases a female’s risk of being the victim of date or acquaintance rape (Fisher et al. in Carroll, 2007). “Alcohol use in one the strongest predictors of rape and sexual assault on college campuses,” (Carroll, 2016, p. 454). Krebs et al. (2009) found that over 80% of sexual assaults on college campuses involved alcohol. One study found that 15% of young women experienced incapacitated rape during their first year of college. These female students were taken advantage of while unconscious and therefore could not give consent since they did not know what was happening. Being intoxicated increases a female’s risk of being the victim of date or acquaintance rape (Carroll, 2007). And, she is more likely to blame herself and to be blamed by others if she was intoxicated when raped. Males increase their risk of being accused of rape if they are drunk when an incidence occurred (Carroll, 2007).

Another recent study revealed that about 1 in 13 American college students report having been drugged, or suspect that they were drugged. Drink spiking, or adding drugs to a person’s drink without his or her knowledge or consent, is one of the most common ways in which college students facilitate sexual assault. Of the students who reported being drugged, 79 percent were female. Those who drugged others, or knew someone who had done so, reported that Rohypnol was used 32 percent of the time. Rohypnol is a brand name for flunitrazepam, which is a powerful sedative that depresses the central nervous system. Rohypnol is not legally available for prescription in the United States. The most common names for Rohypnol are roofies, forget-me drug, date rape drug, roche, and ruffles. The drug is popular on high school and college campuses and at raves and clubs.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem typically rises from the age ranges of 23 to 29 and there is a gradual increase into adulthood peaking in midlife (Robins et al., 2002). The increase in self-esteem may be attributed to completion of maturational changes associated with puberty, changes in autonomy, and other positive aspects of emerging adulthood. Erol and Orth (2012) examined individuals’ self-esteem from ages 14 years to 30 years of age using a section of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. The study collected information from eight assessments sampling 7,100 individuals age 14 to 30 years (born between 1970 and 1993). The authors took information across participants and used a longitudinal analysis technique to estimate growth over a period of time (latent growth curve analyses). The results indicated that self-esteem appears to increase more slowly in young adulthood (Erol & Orth, 2012). The study did not have any sex differences in their self-esteem trajectories, although males typically report higher self-esteem than females (Robins et al., 2002). Erol and Orth did find some differences in self-esteem trajectories for different ethnic identities across adolescence into young adulthood. In adolescence, Hispanics had lower self-esteem than Blacks and Whites, but the self-esteem of Hispanics subsequently increased more strongly, so that at age 30 Blacks and Hispanics had higher self-esteem than Whites. At each age, there were predictors of higher self-esteem. These were emotionally stable, extraversion, and conscientious. Individuals who are emotionally stable, extraverted and conscientious experienced higher self-esteem than emotionally unstable, introverted, and less conscientious individuals. Moreover, at each age, a high sense of mastery, lower risk taking, and better health predicted higher self-esteem. Orth and colleagues also identified that low self-esteem is a risk factor for depressive symptoms at all phases of the adult life span (Orth et al., 2009).

We’ve seen with Erikson that identity largely involves occupation and, as we will learn in the next section, Levinson found that young adults typically form a dream about work (though females may have to choose to focus relatively more on work or family initially with “split” dreams). The American School Counselor Association recommends that school counselors aid students in their career development beginning as early as kindergarten and continue this development throughout their education.

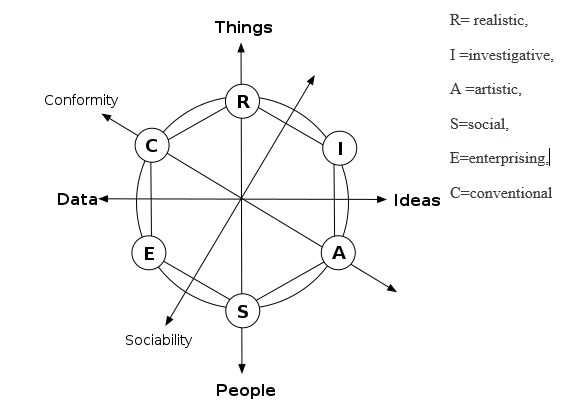

One of the most well-known theories about career choice is from John Holland (1985), who proposed that there are six personality types (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional), as well as varying types of work environments. The better matched one’s personality is to the workplace characteristics, the more satisfied and successful one is predicted to be with that career or vocational choice. Research support has been mixed for Holland’s career personality theory and we should note that there is more to satisfaction and success in a career than one’s personality traits or likes and dislikes. For instance, education, training, and abilities need to match the expectations and demands of the job, plus the state of the economy, availability of positions, and salary rates may play practical roles in choices about work.

Levinson’s Theory (Ob 8)

In 1978, Daniel Levinson published a book entitled The Seasons of a Man’s Life in which he presented a theory of development in adulthood. Levinson’s work was based on in-depth interviews with 40 men between the ages of 35-45. He later conducted interviews with women as well (1996). According to Levinson, these adults have an image of the future that motivates them. This image is called “the dream.” For the men interviewed, it was a dream of how their career paths would progress and where they would be at midlife. Women held a “split dream”; an image of the future in both work and family life and a concern with the timing and coordination of the two. For women, working outside the home and taking care of their families were perceived as separate and competing for their time and attention. Hence, one aspect of the women’s dreams was focused on one goal for several years and then their time and attention shifted towards the other, often resulting in delays in women’s career dreams. One’s dreams for each period of adulthood may or may not measure up to its image as the realization of it moves closer. If it does, all is well. But if it does not, the image must be replaced or modified. And so, in adulthood, plans are made, efforts follow, and plans are reevaluated. There are transition periods for each phase where dreams may align to different social aspects. This creating and recreating characterizes Levinson’s theory. Levinson’s theory includes transition stages that are presented below (Levinson, 1978). He suggests that the period of transition last about 5 years and periods of “settling down” last about 7 years.

The ages presented below are based on life in the middle class about 30 years ago. Think about how these ages and transitions might be different today.

- Early adult transition (17-22): Leaving home, leaving family; making first choices about career and education

- Entering the adult world (22-28): Committing to an occupation, defining goals, finding intimate relationships

- Age 30 transition (28-33): Reevaluating those choices and perhaps making modifications or changing one’s attitude toward love and work

- Settling down (33 to 40): Reinvesting in work and family commitments; becoming involved in the community

- Midlife transition (40-45): Reevaluating previous commitments; making dramatic changes if necessary; giving expression to previously ignored talents or aspirations; feeling more of a sense of urgency about life and its meaning

- Entering middle adulthood (45-50): Committing to new choices made and placing one’s energies into these commitments

Levinson’s theory shares that adulthood is a period of building and rebuilding one’s life. Many of the decisions that are made in early adulthood are made before a person has had enough experience to really understand the consequences of such decisions. And, perhaps, many of these initial decisions are made with one goal in mind to be seen as an adult. As a result, early decisions may be driven more by the expectations of others. For example, imagine someone who chose a career path based on others’ advice but now finds that the job is not what was expected. At the age of 30, the transition may involve recommitting to the same job, not because it’s stimulating, but because it pays well. Settling down may involve settling down with a new set of expectations for that job. As the adult gains status, he or she may be freer to make more independent choices. And sometimes these are very different from those previously made. The midlife transition differs from the age 30 transition in that the person is more aware of how much time has gone by and how much time is left. This brings a sense of urgency and impatience about making changes. The future focus of early adulthood gives way to an emphasis on the present in midlife. Overall, Levinson calls our attention to the dynamic nature of adulthood.

How well do you think Levinson’s theory translates culturally? Do you think that personal desire and concern with reconciling dreams with the realities of work and family is equally important in all cultures? Do you think these considerations are equally important in all social classes, races, and ethnic groups? Why or why not? How might this model be modified in today’s economy?

How well do you think Levinson’s theory translates culturally? Do you think that personal desire and concern with reconciling dreams with the realities of work and family is equally important in all cultures? Do you think these considerations are equally important in all social classes, races, and ethnic groups? Why or why not? How might this model be modified in today’s economy?

Conclusion

The new life stage of emerging adulthood has spread rapidly in the past half-century and is continuing to spread. Now that the transition to adulthood is later than in the past, is this change positive or negative for emerging adults and their societies? Certainly, there are some negatives. It means that young people are dependent on their parents for longer than in the past, and they take longer to become fully contributing members of their societies. A substantial proportion of them have trouble sorting through the opportunities available to them and struggle with anxiety and depression, even though most are optimistic. However, there are advantages to having this new life stage as well. By waiting until at least their late twenties to take on the full range of adult responsibilities, emerging adults are able to focus on obtaining enough education and training to prepare themselves for the demands of today’s information- and technology-based economy. Also, it seems likely that if young people make crucial decisions about love and work in their late twenties or early thirties rather than their late teens and early twenties, their judgment will be more mature and they will have a better chance of making choices that will work out well for them in the long run.

Chapter Review Practice Quiz

Chapter 8 Key terms (see Glossary)

| binge drinking |

|

dialetical thought

|

| dichotomies |

|

emerging adulthood

|

| gender |

| hormones |

| NEET |

|

physiological peak

|

|

postsecondary education

|

|

reflective thought

|

|

sexual response cycle

|

|

socioeconomic status

|

|

tertiary education

|

Media Attributions

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_01 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_02 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_7_Early_Adolescence_Include_V3_01 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_03 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_04 © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_7_Early_Adolescence_Include_V3_02 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_7_Early_Adolescence_Include_V3_03 © Pxhere is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- image2

- OSX_Lifespan_11_05_EducLevel

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_08 © Jirka Matousek is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_06 © Erin Kelly is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_7_Early_Adolescence_Include_V3_05 © Elizabeth Weaver II is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Private: Chapter_7_Early_Adolescence_Include_V3_06 © Flickr is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_07 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_8_Emerging_Adulthood_iNCLUDE_v3_01 © Wikicommons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

late teens to mid-20s, considered extension for industrialized countries, Age of identity exploration.

Age of instability.

Age of self-focus.

Age of feeling in between.

Age of possibilities.

is a way to identify families and households based on their shared levels of education, income, and occupation

any formal education that takes place after high school, including vocational training, two-year community college programs, and four-year university degrees

education for people above school age, including college, university, and vocational courses

early - mid 20s is “prime of your life” as your reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity are operating at their best.

a division into two especially mutually exclusive or contradictory groups or entities

ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions

a process that involves actively evaluating information and beliefs using evidence and past experiences

Not in Employment, Education or Training

sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity

a product of living cells that circulates in body fluids (such as blood) or sap and produces a specific often stimulatory effect on the activity of cells usually remote from its point of origin

wide range of possible identities, including cisgender, transgender, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, bigender, pangender, ambigender, nongendered, intergender, and Two-spirit which is a modern umbrella term used by some indigenous North Americans to describe gender-variant individuals in their communities

over consumption of alcohol where blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL