Chapter 10: Middle Adulthood

Objectives

Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- Explain trends in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy.

- List developmental tasks of midlife.

- Summarize physical changes and health concerns that occur in midlife.

- Describe physical changes that occur during menopause and the variations in cultural responses to menopause.

- Contrast menopause and andropause.

- Explain the relationships between the climacteric and sexual expression.

- Discuss the impact of diet and exercise on health in midlife.

- Describe cognitive development in midlife including differences in crystallized and fluid intelligence.

- Contrast the expert and the novice.

- Evaluate the notion of the midlife crisis.

- Define kin-keeping and the impact of caregiving.

- Describe Erikson’s stage of generativity vs. stagnation.

- Describe personality changes in midlife.

- Discuss communication in marriage.

- Describe the stations of divorce.

- Discuss issues related to recoupling including remarriage and cohabitation.

- Describe grandparenting styles.

- Discuss work-related issues in midlife

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Middle Adulthood (Ob 1)

Middle adulthood (or midlife) refers to the period of the lifespan between young adulthood and old age. This is a relatively new period of life. One hundred years ago, life expectancy in the United States was about 47 years. This period lasts from 20 to 40 years depending on how these stages, ages, and tasks are culturally defined. The most common age definition is from 40 to 65, but there can be a range of up to 10 years on either side of these numbers. For the purpose of this text and this chapter, we will define middle adulthood from age 40 to 65. Research on this period of life is relatively new and many aspects of midlife are still being explored. This may be the least studied period of the lifespan.

Midlife as a central, pivotal period in the life course. It falls at a critical juncture examining changes that go on physically, cognitively, and socially. Midlife has a somewhat unique advantage in the life course with the juxtaposition of gains and losses for aspects of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes that go on. We will identify social benefits and complexities in middle adulthood in addition to identifying aspects of decline in cognitive and physical functions. And this is a varied group. We can see considerable differences in individuals within this developmental stage. There is much to learn about this group.

Developmental Tasks (Ob 2)

Lachman (2004) provides a comprehensive overview of the challenges facing midlife adults. These include:

- Losing parents and experiencing associated grief.

- Launching children into their own lives.

- Adjusting to home life without children (often referred to as the empty nest).

- Dealing with adult children who return to live at home (known as boomerang children in the United States).

- Becoming grandparents.

- Preparing for late adulthood.

- Acting as caregivers for aging parents or spouses.

We will explore these tasks and this stage of life further in this chapter.

Physical Development in Midlife (Ob 3)

There are few biologically based physical changes in midlife other than changes in vision, more joint pain, and weight gain (Lachman, 2004).

Hair: When asked to imagine someone in middle adulthood, we often picture someone with the beginnings of wrinkles and gray or thinning hair. What accounts for these physical changes? Hair color is due to a pigment called melanin which is produced by hair follicles (Martin, 2014). With aging, the hair follicles produce less melanin and this causes the hair to become gray. Hair color typically starts turning lighter at the temples, but eventually, all the hair will become white. For many, graying begins in the 30s, but it is largely determined by your genes. Gray hair occurs earlier in white people and later in Asians. Genes also determine how much hair remains on your head. Almost everyone has some hair loss with aging, and the rate of hair growth slows with aging. Many hair follicles stop producing new hairs and hair strands become smaller. Men begin showing signs of balding by 30 and some are nearly bald by 60. Male-pattern baldness is related to testosterone and is identified by a receding hairline followed by hair loss at the top of the head. Women can also develop female patterned baldness as their hair becomes less dense and the scalp becomes visible (Martin, 2014). Sudden hair loss, however, can be a symptom of a health problem.

Skin: Skin continues to dry out and is prone to more wrinkling, particularly on the sensitive face area. Wrinkles, or creases in the skin, are a normal part of aging. As we get older, our skin dries and loses the underlying layer of fat, so our face no longer appears smooth. Loss of muscle tone and thinning skin can make the face appear flabby or drooping. Although wrinkles are a natural part of aging and genetics plays a role, frequent sun exposure and smoking will cause wrinkles to appear sooner. Dark spots and blotchy skin also occur as one ages and are due to exposure to sunlight (Moskowitz, 2014). Blood vessels become more apparent as the skin continues to dry and get thinner.

Lungs: The lungs serve two functions: Supply oxygen and remove carbon dioxide. Thinning of the bones with age can change the shape of the rib cage and result in a loss of lung expansion. Age-related changes in muscles, such as the weakening of the diaphragm, can also reduce lung capacity. Both of these changes will lower oxygen levels in the blood and increase the levels of carbon dioxide. Experiencing shortness of breath and feeling tired can result (NIH, 2014b). In middle adulthood, these changes and their effects are often minimal, especially in people who are non-smokers and physically active. However, in those with chronic bronchitis, or who have experienced frequent pneumonia, asthma other lung-related disorders, or who are smokers, the effects of these normal age changes can be more pronounced.

Vision: Vision is affected by age. As we age, the lens of the eye gets larger, but the eye loses some of the flexibility required to adjust to visual stimuli. Middle-aged adults often have trouble seeing up close as a result. A typical change of the eye due to age is presbyopia, which is Latin for “old vision.” It refers to a loss of elasticity in the lens of the eye that makes it harder for the eye to focus on objects that are closer to the person. When we look at something far away, the lens flattens out; when looking at nearby objects, tiny muscle fibers around the lens enable the eye to bend the lens. With age, these muscles weaken and can no longer accommodate the lens to focus the light. Anyone over the age of 35 is at risk for developing presbyopia.

According to the National Eye Institute (NEI) (2016), signs that someone may have presbyopia include:

- Hard time reading small print

- Having to hold reading material farther than arm’s distance

- Problems seeing objects that are close

- Headaches

- Eyestrain

Another common eye problem people experience as they age are floaters, little spots or “cobwebs” that float around the field of vision. They are most noticeable if you are looking at the sky on a sunny day, or at a lighted blank screen. Floaters occur when the vitreous, a gel-like substance in the interior of the eye, slowly shrinks. As it shrinks, it becomes somewhat stringy, and these strands can cast tiny shadows on the retina. In most cases, floaters are harmless, more of an annoyance than a sign of eye problems. However, floaters that appear suddenly, or that darken and obscure vision can be a sign of more serious eye problems, such a retinal tearing, infection, or inflammation. People who are very nearsighted (myopic), have diabetes, or who have had cataract surgery are also more likely to have floaters (NEI, 2009).

During midlife, adults may begin to notice a drop in scotopic sensitivity, the ability to see in dimmer light. By age 60, the retina receives only one-third as much light as it did at age 20, making working in dimmer light more difficult (Jackson & Owsley, 2000). Night vision is also affected as the pupil loses some of its ability to open and close to accommodate drastic changes in light. Eyes become more sensitive to glare from headlights and street lights making it difficult to see people and cars, and movements outside of our direct line of sight (NIH, 2016c).

Hearing: Prior to age 40, about 5.5% of adults report hearing problems. This jumps to 19% among 40 to 69 year-olds (American Psychological Association, 2016). Hearing loss is experienced by about 14 percent of midlife adults (Gratton & Vasquez in Berk, 2007) as a result of being exposed to high levels of noise. Men may experience some hearing loss by 30 and women by 50. High-frequency sounds are the first affected by such hearing loss. This loss accumulates after years of being exposed to intense noise levels. Men are more likely to work in noisy occupations. Hearing loss is also exacerbated by cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, and stroke. Most hearing loss could be prevented by guarding against being exposed to extremely noisy environments. (There is new concern over hearing loss in early adulthood with the widespread use of earbuds)

Taking care of health

Most of the changes that occur in midlife can be easily compensated for (e.g., by buying glasses, exercising, and watching what one eats). Things like eating calcium-rich foods, such as dairy products, almonds, dark leafy greens, salmon, and tofu. Vitamin D helps the body to absorb the calcium in these foods, starting in early adulthod, can strengthen bones and teeth. Additionally, vitamin D is produced naturally by the body but can also be supplemented by foods rich in vitamin D, such as fish, eggs, mushrooms, and vitamin D–fortified foods, such as milk and cereal. Strength training also helps support balance, metabolism, and cognition (Mayo Clinic, 2023).

Hearing aids offer significant benefits for individuals with hearing loss, yet multiple studies and national surveys indicate that only about 14–29% of older adults with hearing loss in the United States use hearing aids, with usage rates increasing with age and severity of hearing loss. Supportive health care for hearing loss is essential as untreated hearing loss can hinder work, social interactions, daily activities, and even lead to stress, fatigue, and impaired brain function. Preventative care is important, and most midlife adults experience general good health. However, the percentage of adults who have a disability increases through midlife; while 7 percent of people in their early 40s have a disability, the rate jumps to 30 percent by the early 60s. This increase is highest among those of lower socioeconomic status (Bumpass & Aquilino, 1995).

Midlife adults have to increase their level of exercise, eat less, and watch their nutrition to maintain their earlier physique. However, weight can can happen due to decreased metabolism. Sometimes referred to as the middle-aged spread, the accumulation of fat in the abdomen, is one of the common complaints of midlife adults. Men tend to gain fat on their upper abdomen and back while women tend to gain more fat on their waist and upper arms. Many adults are surprised at this weight gain because their diets have not changed. However, the metabolism slows during midlife by about one-third (Berger, 2005). Recently semaglutide hormone therapies are being used as medical approaches to weight management, particularly for adults at risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Semaglutide acts on the hypothalamus to reduce appetite and food intake, and initial studies have found promising results for patients using these injectable medications to sustain weight loss and lower risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Lincoff et al., 2023). Semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist originally developed for type 2 diabetes, is now FDA-approved as Wegovy for weight management and works by reducing appetite and food intake, with studies showing it helps sustain weight loss and lower cardiovascular and diabetes risk, though more research is needed on its long-term safety and effectiveness.

It becomes important for midlife adults to take preventative measures to enhance physical well-being. Again, lifestyle has a strong impact on the health status of midlife adults. Choosing not to smoke, watch intake of alcohol, have a good diet, reduce stress and keep up on physical activity can improve overall health. Those midlife adults who have a strong sense of mastery and control over their lives, who engage in challenging physical and mental activity, who engage in weight bearing exercise, monitor their nutrition, and make use of social resources are most likely to enjoy a plateau of good health through these years (Lachman, 2004).

Health Concerns

Sarcopenia: The loss of muscle mass and strength that occurs with aging is referred to as Sarcopenia (Morley et al., 2001). Sarcopenia is thought to be a significant factor in the frailty and functional impairment that occurs when older. The decline of growth and anabolic hormones, especially testosterone, and decreased physical activity have been implicated as causes of sarcopenia (Proctor et al., 1998). This decline in muscle mass can occur as early as 40 years of age and contributes significantly to a decrease in life quality, increase in health care costs, and early death in older adults (Karakelides & Nair, 2005). In middle age, muscular performance gradually declines at a rate of approximately five percent every ten years. While men and women generally experience a loss of 30 to 40 percent of their functional strength, people can counteract the loss of muscle mass in later years by engaging in a strength training regimen. Sarcopenia has only recently been recognized an independent disease entity since 2016 (ICD-10). In 2018 the U.S. Center for Disease Control and prevention assigned sarcopenia its own discrete medical code. Exercise is certainly important to increase strength, aerobic capacity, muscle protein synthesis, and new nerve growth (Piasescki et al, 2018), but unfortunately, it does not reverse all the age-related changes that occur. The muscle-to-fat ratio for both men and women also changes throughout middle adulthood, with an accumulation of fat in the stomach area. Human beings reach peak bone mass around 35-40. Mobility can central concern, and some researchers are now identifying some conditions like osteosarcopenia, which describes the decline of both muscle tissue (sarcopenia) and bone tissue (osteoporosis).

Heart Disease: According to the most recent National Vital Statistics Reports (Xu et al., 2016) heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death for Americans as it claimed 23.5% of those who died in 2013. It is also the number one cause of death worldwide (WHO, 2019). Heart disease develops slowly over time and typically appears in midlife (Hooker & Pressman, 2016). Heart disease can include heart defects and heart rhythm problems, as well as narrowed, blocked, or stiffened blood vessels referred to as a cardiovascular disease. The blocked blood vessels prevent the body and heart from receiving adequate blood. Atherosclerosis, or a buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries, is the most common cause of cardiovascular disease. The plaque buildup thickens the artery walls and restricts the blood flow to organs and tissues. Cardiovascular disease can lead to a heart attack, chest pain (angina), or stroke (Mayo Clinic, 2014a).

Complications of heart disease can include heart failure when the heart cannot pump enough blood to the meet the body’s needs, and a heart attack, when a blood clot blocks the blood flow to the heart. This blockage can damage or destroy a part of the heart muscle, and atherosclerosis is a factor in a heart attack. Treatment for heart disease includes medication, surgery, and lifestyle changes including exercise, healthy diet, and refraining from smoking.

Sudden cardiac arrest is the unexpected loss of heart functioning, breathing, and consciousness, often caused by an arrhythmia or abnormal heartbeat. The heartbeat may be too quick, too slow, or irregular. With a healthy heart, it is unlikely for a fatal arrhythmia to develop without an outside factor, such as an electric shock or illegal drugs. If not treated immediately, sudden cardiac arrest can be fatal and result in sudden cardiac death.

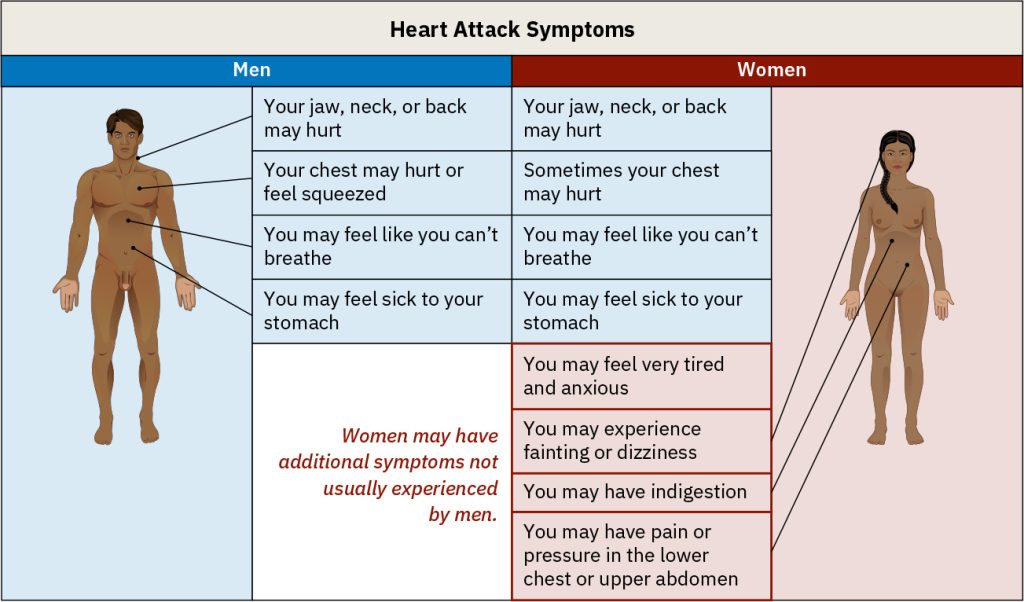

Symptoms of cardiovascular diseases (including heart disease) differ for men and women. Males are more likely to suffer chest pain. Symptoms may include acute [chest] pain, weakness, dizziness, confusion, and shortness of breath. In fact, chest pain, such as pressure, squeezing, or fullness is a major indicator that doctors look for when diagnosing a heart attack (Becker, 2005). However, women are more likely to demonstrate shortness of breath, nausea, and extreme fatigue. The three most common early warning symptoms among women are extreme fatigue, trouble sleeping, and shortness of breath (even when not engaging in physical exertion). Other symptoms can also include pain in the arms, legs, neck, jaw, throat, abdomen, or back (Mayo Clinic, 2014a). It is important for women and their loved ones to be aware of these symptoms and get medical attention immediately in an acute situation. The most common acute symptoms include shortness of breath, weakness, and fatigue. In addition, prevention and early intervention are also important. A diet low in trans and saturated fat, no smoking, and regular exercise and stress reduction are good preventative measures.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a serious health problem that occurs when the blood flows with a greater force than normal. One in three American adults (70 million people) have hypertension and only half have it under control (Nwankwo, Yoon, Burt, & Gu, 2013). It can strain the heart, increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, or damage the kidneys (CDC, 2014a). Uncontrolled high blood pressure in early and middle adulthood can also damage the brain’s white matter (axons) and may be linked to cognitive problems later in life (Maillard et al., 2012). Normal blood pressure is under 120/80. The first number is the systolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart beats. The second number is the diastolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart is at rest. High blood pressure is sometimes referred to as the silent killer, as most people with hypertension experience no symptoms.

High Cholesterol: Cholesterol is a waxy fatty substance carried by lipoprotein molecules in the blood. It is created by the body to create hormones and digest fatty foods and is also found in many foods. Your body needs cholesterol, but too much can cause heart disease and stroke. Two important kinds of cholesterol are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The third type of fat is called triglycerides. Your total cholesterol score is based on all three types of lipids. LDL cholesterol makes up the majority of the body’s cholesterol, however, it is often referred to as “bad” cholesterol because at high levels it can form plaque in the arteries leading to heart attack and stroke. HDL cholesterol often referred to as “good” cholesterol, absorbs cholesterol, and carries it back to the liver, where it is then flushed from the body. Higher levels of HDL can reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. Triglycerides are a type of fat in the blood used for energy. High levels of triglycerides can also increase your risk for heart disease and stroke when coupled with high LDL and low HDL. All adults 20 or older should have their cholesterol checked. In early adulthood, doctors may check every few years if the numbers have previously been normal, and there are no other signs of heart disease. In middle adulthood, this may become part of the annual check-up (CDC, 2015).

Cancer: After heart disease, cancer was the second leading cause of death for Americans in 2013 as it accounted for 22.5% of all deaths (Xu et al., 2016). According to the National Institutes of Health (2015), cancer is the name given to a collection of related diseases in which the body’s cells begin to divide without stopping and spread into surrounding tissues. These extra cells can divide and form growths called tumors, which are typically masses of tissue. Cancerous tumors are malignant, which means they can invade nearby tissues. When removed malignant tumors may grow back. Unlike malignant tumors, benign tumors do not invade nearby tissues. Benign tumors can sometimes be quite large, and when removed usually do not grow back. Although benign tumors in the body are not cancerous, benign brain tumors can be life-threatening. Cancer cells can prompt nearby normal cells to form blood vessels that supply the tumors with oxygen and nutrients, which allows them to grow. These blood vessels also remove waste products from the tumors. Cancer cells can also hide from the immune system, a network of organs, tissues, and specialized cells that protects the body from infections and other conditions. Lastly, cancer cells can metastasize, which means they can break from where they first formed, called primary cancer, and travel through the lymph system or blood to form new tumors in other parts of the body. This new metastatic tumor is the same type as the primary tumor (National Institutes of Health, 2015).

Cancer can start almost anywhere in the human body. While normal cells mature into very distinct cell types with specific functions, cancer cells do not and continue to divide without stopping. Further, cancer cells are able to ignore the signals that normally tell cells to stop dividing or to begin a process known as programmed cell death which the body uses to get rid of unneeded cells. With the growth of cancer cells, normal cells are crowded out and the body is unable to work the way it is supposed to. For example, the cancer cells in lung cancer form tumors which interfere with the functioning of the lungs and how oxygen is transported to the rest of the body. There are more than 100 types of cancer. The American Cancer Society assemblies a list of the most common types of cancers in the United States. To qualify for the 2016 list, the estimated annual incidence had to be 40,000 cases or more. The most common type of cancer on the list is breast cancer. The next most common cancers are lung cancer and prostate cancer (American Cancer Society, 2016).

Diabetes (Diabetes Mellitus) is a disease in which the body does not control the amount of glucose in the blood. A typical test for diabetes includes a fasting glucose test. This disease occurs when the body does not make enough insulin or does not use it the way it should (NIH, 2016a). Insulin is a type of hormone that helps glucose in the blood enter cells to give them energy. In adults, 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes are type 2 (American Diabetes Association, 2016). Type 2 diabetes usually begins with insulin resistance, a disorder in which the cells in the muscles, liver, and fat tissue do not use insulin properly (CDC, 2014d). As the need for insulin increases, cells in the pancreas gradually lose the ability to produce enough insulin. In some Type 2 diabetics, pancreatic beta cells will cease functioning, and the need for insulin injections will become necessary. Some people with diabetes experience insulin resistance with only minor dysfunction of the beta cell secretion of insulin. Other diabetics experience only slight insulin resistance, with the primary cause being a lack of insulin secretion (CDC, 2014d). One in three adults are estimated to have prediabetes, and 9 in 10 of them do not know. According to the CDC (2014d) without intervention, 15% to 30% of those with prediabetes will develop diabetes within 5 years. In 2012, 29 million people (over 9% of the population) were living with diabetes in America, most adults age 20 and up. The median age of diagnosis is 54 (CDC, 2014d). During middle adulthood, the number of people with diabetes dramatically increases; with 4.3 million living with diabetes prior to age 45, to over 13 million between the ages of 45 to 64; a four-fold increase. Men are slightly more likely to experience diabetes than are women.

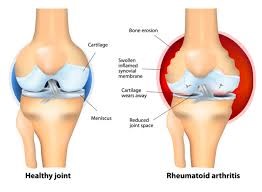

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory disease that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in the joints (NIH, 2016b). Between 30 and 60 is the typical onset age for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with the peak onset for women being sometime in the early 40s. RA occurs when the immune system attacks the membrane lining the joints. RA is the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis, which is the normal wear and tear the joints. Unlike osteoarthritis, RA is symmetric in its attack of the body, thus, if one shoulder is affected so is the other. In addition, those with RA may experience fatigue and fever.

Common features of RA (NIH, 2016b):

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- Symmetrical pattern of affected joints

- Joint inflammation often affecting the wrist and finger joints closest to the hand

- Joint inflammation sometimes affecting other joints, including the neck, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles, and feet

- Fatigue, occasional fevers, a loss of energy

- Pain and stiffness lasting for more than 30 minutes in the morning or after a long rest

- Symptoms that last for many years

About 1.5 million people (approximately 0.6%) of Americans experience rheumatoid arthritis. It occurs across all races and age groups, although the disease often begins in middle adulthood and occurs with increased frequency in older people. Like some other forms of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis occurs much more frequently in women than in men. About two to three times as many women as men have the disease (NIH, 2016b). It affects women more than men by a factor of around 3 to 1. The lifetime risk for RA for women is 3.6% and 1.7% for men (Crowson et al., 2011).

Genes play a role in the development of RA. However, individual genes by themselves confer only a small risk of developing the disease, as some people who have these particular genes never develop RA. Scientists think that something must occur to trigger the disease process in people whose genetic makeup makes them susceptible to rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, some scientists also think hormonal factors may be involved. In women who experience RA, the symptoms may improve during pregnancy and flare after pregnancy. Women who use oral contraceptives may increase their likelihood of developing RA. This suggests hormones, or possibly deficiencies or changes in certain hormones may increase the risk of developing RA in a genetically susceptible person (NIH, 2016b).

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect virtually every area of a person’s life, and it can interfere with the joys and responsibilities of work and family life. Fortunately, current treatment strategies allow most people with RA to lead active and productive lives. Pain-relieving drugs and medications can slow joint damage, and establishing a balance between rest and exercise can also lessen the symptoms of RA (NIH, 2016b).

Digestive Issues

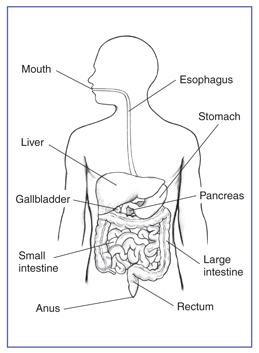

In the U.S. 60 million people experience heartburn at least once a month, and 15 million experience it every day. Heartburn, also called acid indigestion or pyrosis, is a common digestive problem in adults and is the result of stomach acid backing up into the esophagus. Prolonged contact with the digestive juices injures the lining of the esophagus and causes discomfort. Heartburn that occurs more frequently may be due to gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD. Normally the lower sphincter muscle in the esophagus keeps the acid in the stomach from entering the esophagus. In GERD this muscle relaxes too frequently and the stomach acid flows into the esophagus. Prolonged problems with heartburn can lead to more serious complications, including esophageal cancer, one of the most lethal forms of cancer in the U.S. Problems with heartburn can be linked to eating fatty or spicy foods, caffeine, smoking, and eating before bedtime (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016a).

Gallstones are present in about 20% of women and 10% of men over the age of 55 (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b). Gallstones are hard particles, including fatty materials, bile pigments, and calcium deposits, that can develop in the gallbladder. Ranging in size from a grain of sand to a golf ball, they typically take years to develop, but in some people have developed over the course of a few months. About 75% of gallstones do not create any symptoms, but those that do may cause sporadic upper abdominal pain when stones block bile or pancreatic ducts. If stones become lodged in the ducts, it may necessitate surgery or other medical intervention as it could become life-threatening if left untreated (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b). Risk factors for gallstones include a family history of gallstones, diets high in calories and refined carbohydrates (such as, white bread and rice), diabetes, metabolic syndrome, Crohn’s disease, and obesity, which increases the cholesterol in the bile and thus increases the risk of developing gallstones (NIH, 2013).

Gallstones are present in about 20% of women and 10% of men over the age of 55 (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b). Gallstones are hard particles, including fatty materials, bile pigments, and calcium deposits, that can develop in the gallbladder. Ranging in size from a grain of sand to a golf ball, they typically take years to develop, but in some people have developed over the course of a few months. About 75% of gallstones do not create any symptoms, but those that do may cause sporadic upper abdominal pain when stones block bile or pancreatic ducts. If stones become lodged in the ducts, it may necessitate surgery or other medical intervention as it could become life-threatening if left untreated (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b). Risk factors for gallstones include a family history of gallstones, diets high in calories and refined carbohydrates (such as, white bread and rice), diabetes, metabolic syndrome, Crohn’s disease, and obesity, which increases the cholesterol in the bile and thus increases the risk of developing gallstones (NIH, 2013).

The Climacteric (Ob 4, Ob 5, Ob 6)

One biologically based change that occurs during midlife is the climacteric. The climacteric, or the midlife transition when fertility declines, is biologically based but impacted by the environment. During midlife, men may experience a reduction in their ability to reproduce. Women, however, lose their ability to reproduce once they reach menopause.

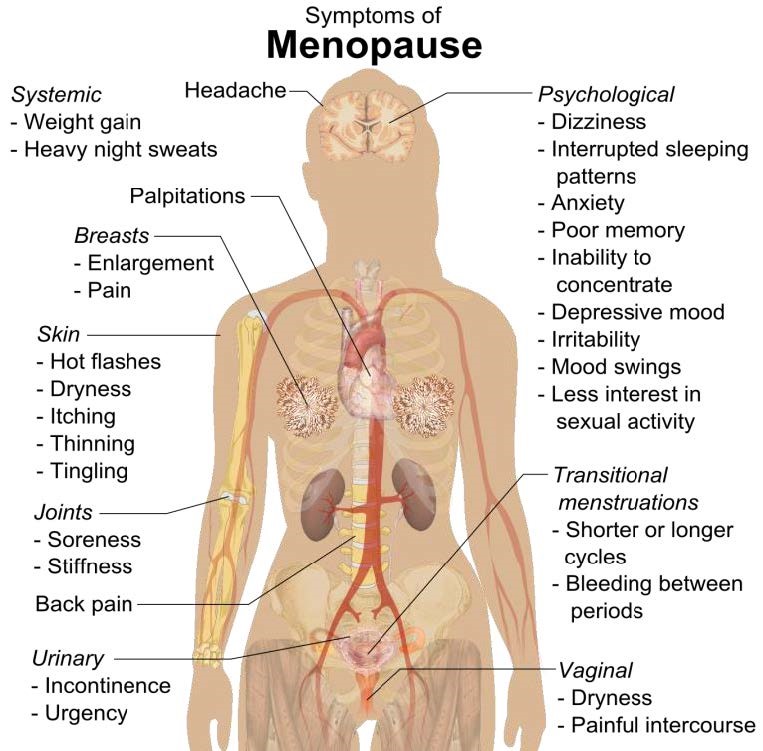

Menopause for women: Perimenopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases. Menopause is defined as 12 months without menstruation. After menopause, a woman’s menstruation ceases (U. S. National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health, 2007).

Changes typically occur between the mid-40s and mid-50s. Many women begin experiencing symptoms in their 40s. These symptoms occur during perimenopause, which can occur 2 to 8 years before menopause (Huang, 2007). A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women, however, may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The median age range for women to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes waterier. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner, and less elastic. The shifting hormones can contribute to the inability to fall asleep. Additionally, the declining levels of estrogen may make a woman more susceptible to environmental factors and stressors which disrupt sleep. A hot flash is a surge of adrenaline that can awaken the brain from sleep. It often produces sweat and a change of temperature that can be disruptive to sleep and comfort levels. Unfortunately, it may take time for adrenaline to recede and allow sleep to occur again (National Sleep Foundation, 2016). Decreased estrogen can cause osteoporosis resulting in decreased bone mass. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are often associated with menopause, but they are not menopausal (Avis et al., 2001; Rossi, 2004). Weight gain can occur due to an increase in intra-abdominal fat followed by a loss of lean body mass after menopause (Morita et al., 2006). Consequently, women may need to change their lifestyle to counter any weight gain. Most American women go through menopause with few problems (Carroll, 2016). Overall, menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004).

Hormone Replacement Therapy: Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement has changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. However, more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NIH, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy. If so, they can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Cultural influences seem to also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. Numerous international students enrolled in my class have expressed their disbelief when we discuss menopause. For example, after listing the symptoms of menopause, a woman from Kenya or Nigeria might respond, “We do not have this in my country or if we do, it is not a big deal” to which some U. S. students reply, “I want to go there!” Indeed, there are cultural variations in the experience of menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are experienced by 75 percent of women in Western cultures, but by less than 20 percent of women in Japan (Obermeyer in Berk, 2007).

Women in the United States respond differently to menopause depending upon the expectations they have for themselves and their lives. White, career-oriented women, African-American, and Mexican-American women overall tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Nevertheless, there has been a popular tendency to erroneously attribute frustrations and irritations expressed by women of menopausal age to menopause and thereby not take her concerns seriously. Fortunately, many practitioners in the United States today are normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause.

Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement have changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. But more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NLM/NIH, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy. But if so, they can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Andropause for men: Do males experience a climacteric? They do not lose their ability to reproduce as they age, although they do tend to produce lower levels of testosterone and fewer sperm. Andropause is related to decreases in testosterone levels that occur with age. However, men are capable of reproduction throughout life. It is natural for sex drive to diminish slightly as men age, but a lack of sex drive may be a result of extremely low levels of testosterone. About 5 million men experience low levels of testosterone that results in symptoms such as a loss of interest in sex, loss of body hair, difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection, loss of muscle mass, and breast enlargement. Low testosterone levels may be due to glandular disease such as testicular cancer. Testosterone levels can be tested and if they are low, men can be treated with testosterone replacement therapy. This can increase sex drive, muscle mass, and beard growth. However, long term HRT for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer (The Patient Education Institute, 2005).

Although males can continue to father children throughout middle adulthood, erectile dysfunction (ED) becomes more common. Erectile dysfunction refers to the inability to achieve an erection or an inconsistent ability to achieve an erection (Swierzewski, 2015). Intermittent ED affects as many as 50% of men between the ages of 40 and 70. About 30 million men in the United States experience chronic ED, and the percentages increase with age. Approximately 4% of men in their 40s, 17% of men in their 60s, and 47% of men older than 75 experience chronic ED. Causes for ED are primarily due to medical conditions, including diabetes, kidney disease, alcoholism, and atherosclerosis (build-up of plaque in the arteries). Overall, diseases account for 70% of chronic ED, while psychological factors, such as stress, depression and anxiety account for 10%-20% of all cases. Many of these causes are treatable, and ED is not an inevitable result of aging. Men during middle adulthood may also experience prostate enlargement, which can interfere with urination, and deficient testosterone levels which decline throughout adulthood, but especially after age 50.

The Climacteric and Sexuality (Ob 7)

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age. Midlife adults tend to have sex lives that are very similar to that of younger adults. And many women feel freer and less inhibited sexually as they age. However, a woman may notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal and men may experience changes in their erections from time to time. This is particularly true for men after age 65. As discussed in the previous paragraph, men who experience consistent problems are likely to have medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning (National Institute on Aging, 2005).

Results from the National Social Life Health, and Aging Project indicated that 72% of men and 45.5% of women aged 52 to 72 reported being sexually active (Karraker et al., 2011). Couples continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse. Continued sexual activity is linked to better psychological and cognitive health—including lower depression risk and improved memory—with research suggesting a bidirectional relationship, as both good health can promote sexual activity and sexual intimacy can enhance mood, belonging, and cognitive function, possibly due to neurotransmitter release (Jackson et al, 2019; Wright & Jenks, 2016).

Risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months, however, and couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. In 2014, 16.7% of the country’s new HIV diagnoses (7,391 of 44,071) were among people 50 and older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014e). This was an increase from 15.4% in 2005. Practicing safe sex is important at any age, but unfortunately adults over the age of 40 have the lowest rates of condom use (Center for Sexual Health Promotion, 2010). This low rate of condom use suggests the need to enhance education efforts for older individuals regarding STI risks and prevention. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

Sleep

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (Kasper, 2015), adults require at least 7 hours of sleep per night to avoid the health risks associated with chronic sleep deprivation. Less than 6 hours and more than 10 hours is also not recommended for those in middle adulthood (National Sleep Foundation, 2024). Not surprisingly, many Americans do not receive the 7-9 hours of sleep recommended. In 2013, only 59% of U.S. adults met that standard, while in 1942, 84% did (Jones, 2013). This means 41% of Americans receive less than the recommended amount of nightly sleep. Additional results included that in 1993, 67% of Americans felt they were getting enough sleep, but in 2013 only 56% felt they received as much sleep as needed. According to a 2016 National Center for Health Statistics analysis (CDC, 2016) having children decreases the amount of sleep an individual receives, however, having a partner can improve the amount of sleep for both males and females. Additionally, 43% of Americans in 2013 believed they would feel better with more sleep.

Sleep problems: According to the Sleep in America poll (National Sleep Foundation, 2015), 9% of Americans report being diagnosed with a sleep disorder, and of those 71% have sleep apnea, and 24% suffer from insomnia. Pain is also a contributing factor in the difference between the amount of sleep Americans say they need and the amount they are getting. An average of 42 minutes of sleep debt occur for those with chronic pain, and 14 minutes for those who have suffered from acute pain in the past week. Stress and overall poor health are also key components of shorter sleep duration and worse sleep quality. Those in midlife with lower life satisfaction experienced a greater delay in the onset of sleep than those with higher life satisfaction. Delayed onset of sleep could be the result of worry and anxiety during midlife, and improvements in those areas should improve sleep. Lastly, menopause can affect a woman’s sleep duration and quality (National Sleep Foundation, 2016).

Negative consequences of insufficient sleep: There are many consequences of too little sleep, and they include physical, cognitive, and emotional changes. Sleep deprivation suppresses immune responses that fight off infection and can lead to obesity, memory impairment, and hypertension (Ferrie et al., 2007; Kushida, 2005). Insufficient sleep is linked to an increased risk for colon cancer, breast cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes (Pattison, 2015). A lack of sleep can increase stress as cortisol (a stress hormone) remains elevated which keeps the body in a state of alertness and hyperarousal which increases blood pressure. Sleep is also associated with longevity. Dew et al. (2003) found that older adults who had better sleep patterns also lived longer. During deep sleep, a growth hormone is released which stimulates protein synthesis, breaks down fat that supplies energy, and stimulates cell division. Consequently, a decrease in deep sleep contributes to less growth hormone being released and subsequent physical decline seen in aging (Pattison, 2015). Sleep disturbances can also impair glucose functioning in middle adulthood. Caucasian, African American, and Chinese non-shift-working women aged 48–58 years who were not taking insulin-related medications participated in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Sleep Study and were subsequently examined approximately 5 years later (Taylor et al., 2016). Body mass index (BMI) and insulin resistance were measured at two time points. Results indicated that irregular sleep schedules, including highly variable bedtimes and staying up much later than usual, are associated in midlife women with insulin resistance, which is an important indicator of metabolic health, including diabetes risk. Diabetes risk increases in midlife women and irregular sleep schedules may be an important reason because disrupting circadian timing may impair glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis.

Stress

We all know that stress plays a major role in our mental and physical health, but what exactly is stress? The term stress is defined as a pattern of physical and psychological responses in an organism after it perceives a threatening event that disturbs its homeostasis and taxes its abilities to cope with the event (Hooker & Pressman, 2016). Stress was originally derived from the field of mechanics where it is used to describe materials under pressure. The word was first used in a psychological manner by researcher Hans Selye. Selye (1946) coined the term stressor to label a stimulus that had this effect on the body (that is, causing stress). He developed a model of the stress response called the General Adaptation Syndrome, which is a three-phase model of stress, which includes a mobilization of physiological resources phase, a coping phase, and an exhaustion phase (i.e., when an organism fails to cope with the stress adequately and depletes its resources).

Psychologists have studied stress in a myriad of ways, and it is not just major life stressor (e.g., a family death, a natural disaster) that increase the likelihood of getting sick. Stress can result from negative events, chronically difficult situations, a biological fight-or-flight response, and as clinical illness, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Even small daily hassles, like getting stuck in traffic or fighting with your friend, can raise your blood pressure, alter your stress hormones, and even suppress your immune system function (DeLongis et al., 1988; Twisk et al., 1999). Stress continues to be one of the most important and well-studied psychological correlates of illness because excessive stress causes potentially damaging wear and tear on the body and can influence almost any disease process.

Dispositions and Stress: Negative dispositions and personality traits have been strongly tied to an array of health risks. One of the earliest negative trait-to-health connections was discovered in the 1950s by two cardiologists. They made the interesting discovery that there were common behavioral and psychological patterns among their heart patients that were not present in other patient samples. This pattern included being competitive, impatient, hostile, and time urgent. These patterns of behavior were associated with double the risk of heart disease as compared with those who did not display those behaviors (Friedman & Rosenman, 1959). Since the 1950s, researchers have discovered that it is the hostility and competitiveness components of personality are especially harmful to heart health (Irribarren et al., 2000; Matthews et al., 1977; Miller et al., 1996). Hostile individuals are quick to get upset, and this angry arousal can damage the arteries of the heart. In addition, given their negative personality style, hostile people often lack a health-protective supportive social network.

Social Relationships and Stress: Research has shown that the impact of social isolation on our risk for disease and death is similar in magnitude to the risk associated with smoking regularly (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; House et al., 1988). In fact, the importance of social relationships for our health is so significant that some scientists believe our body has developed a physiological system that encourages us to seek out our relationships, especially in times of stress (Taylor et al., 2000). Social integration is the concept used to describe the number of social roles that you have (Cohen & Willis, 1985). For example, you might be a daughter, a basketball team member, a Humane Society volunteer, a coworker, or a student. Maintaining these different roles can improve your health via encouragement from those around you to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Those in your social network might also provide you with social support (e.g., when you are under stress). This support might include emotional help (e.g., a hug when you need it), tangible help (e.g., lending you money), or advice. By helping to improve health behaviors and reduce stress, social relationships can have a powerful, protective impact on health, and in some cases, might even help people with serious illnesses stay alive longer (Spiegel et al., 1989).

Social support is important to buffer stress, but caregiving and spousal care can add stress. A disabled child, spouse, parent, or other family member is part of the lives of some midlife adults. Caregiving for a young or adult child with special needs was associated with poorer global health and more physical symptoms among both fathers and mothers (Seltzer et al., 2011). Stress is felt when a caregiving spouse feels strain (Beach et al., 2000; Krause et al., 1992; Schulz et al., 1997). Women experience more caregiving burden than men, despite similar caregiving situations (Gibbons et al., 2014; Torti et al., 2004; Yeager et al., 2010). Women do not use more external support because they feel responsible to assume the caregiving roles (Torti et al, 2004) and have concerns with the opinions of others if they accepted help (Arai et al., 2000). Of concern for caregiving is that disabled males are more aggressive than females, especially males with dementia who display more physical and sexual aggression toward their caregivers (Eastley & Wilcock, 1997; Zuidema et al., 2009).

Exercise, Nutrition, Coping, and Health (Ob 8, Ob 9)

Lifestyle has a strong impact on the health status of midlife adults. Smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, poor diet, stress, physical inactivity, and chronic diseases such as diabetes or arthritis reduce overall health. It becomes important for midlife adults to take preventative measures to enhance physical well-being. Those midlife adults who have a strong sense of mastery and control over their lives, who engage in challenging physical and mental activity, who engage in weight-bearing exercise, monitor their nutrition, and make use of social resources are most likely to enjoy a plateau of good health through these years (Lachman, 2004). This next section reviews positive ways to keep health in middle adulthood.

Exercise

The impact of exercise: Exercise is a powerful way to combat the changes we associate with aging. Exercise plays an important role in counteract normal aging. Exercise builds muscle, increases metabolism, helps control blood sugar, increases bone density, and relieves stress. Unfortunately, fewer than half of midlife adults’ exercise and only about 20 percent exercise frequently and strenuously enough to achieve health benefits. Exercise increases the levels of serotonin (Young, 2007). Physical activity is also related to reductions in depression and anxiety (De Moor et al., 2006). For example, individuals who regularly exercise are less depressed or anxious than those who do not (De Moor et al., 2006). The health benefits that walking and other physical activity have on the nervous system are becoming increasingly obvious to those who study aging. Adami et al (2018) found pronounced links between weight-bearing exercise and neuron production. Many studies suggest that voluntary physical activity extends and improves quality of life. Such studies show that even moderate physical activity can bring large gains. Exercise tends to reduce and prevent behaviors such as smoking, alcohol, and gambling, and to regulate the impulse for hunger and satiety (Vatansever-Ozen et al., 2011; Tiryaki-Sonmez et al., 2015).

The best exercise programs are those that are engaged in regularly-regardless of the activity. But a well-rounded program that is easy to follow includes walking and weight training. Having a safe, enjoyable place to walk can make a difference in whether or not someone walks regularly. Weight lifting and stretching exercises at home can also be part of an effective program. Exercise is particularly helpful in reducing stress in midlife. Walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming can release the tension caused by stressors. And learning relaxation techniques can have healthful benefits. Exercise can be thought of as preventative health care; promoting exercise for the 78 million “baby boomers” may be one of the best ways to reduce health care costs and improve quality of life (Shure & Cahan, 1998).

Nutrition

Nutritional concerns: Aging brings about a reduction in the number of calories a person requires. Many Americans respond to weight gain by dieting. However, eating less does not typically mean eating right and people often suffer vitamin and mineral deficiencies as a result. Very often, physicians will recommend vitamin supplements to their middle-aged patients.

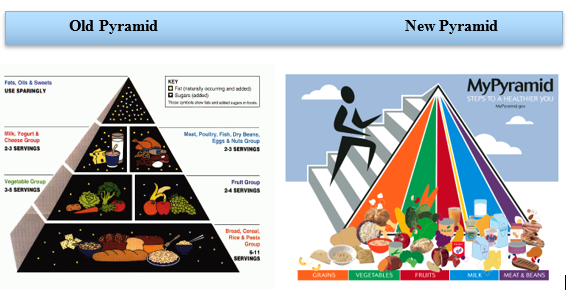

The new food pyramid: The ideal diet is one low in fat, sugar, high in fiber, low in sodium, and cholesterol. In 2005, the Food Pyramid, a set of nutritional guidelines established by the U. S. Government was updated to accommodate new information on nutrition and to provide people with guidelines based on age, sex, and activity levels.

The ideal diet is also low in sodium (less than 2300 mg per day). Sodium causes fluid retention which may, in turn, exacerbate high blood pressure. The ideal diet is also low in cholesterol (less than 300 mg per day). The ideal diet is also one high in fiber. Fiber is thought to reduce the risk of certain cancers and heart disease. Finally, an ideal diet is low in sugar. Sugar is not only a problem for diabetics; it is also a problem for most people. Sugar satisfies the appetite but provides no protein, vitamins, or minerals. It provides empty calories. High starch diets are also a problem because starch is converted to sugar in the body. A 1-2 ounce serving of red wine (or grape juice) can have beneficial effects as well. Red wine can increase “good cholesterol” or HDLs (high-density lipoproteins) in the blood and provides antioxidants important to combating aging.

The ideal diet is also low in sodium (less than 2300 mg per day). Sodium causes fluid retention which may, in turn, exacerbate high blood pressure. The ideal diet is also low in cholesterol (less than 300 mg per day). The ideal diet is also one high in fiber. Fiber is thought to reduce the risk of certain cancers and heart disease. Finally, an ideal diet is low in sugar. Sugar is not only a problem for diabetics; it is also a problem for most people. Sugar satisfies the appetite but provides no protein, vitamins, or minerals. It provides empty calories. High starch diets are also a problem because starch is converted to sugar in the body. A 1-2 ounce serving of red wine (or grape juice) can have beneficial effects as well. Red wine can increase “good cholesterol” or HDLs (high-density lipoproteins) in the blood and provides antioxidants important to combating aging.

Coping

Stress Management: Around three-quarters of adults (76%) said they have experienced health impacts due to stress in the prior month (American Psychological Association, 2022). Given that the sources of our stress are often difficult to change (e.g., personal finances, current job), a number of interventions have been designed to help reduce the aversive responses to duress, especially related to health. For example, relaxation activities and forms of meditation are techniques that allow individuals to reduce their stress via breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, and mental imagery. Physiological arousal from stress can also be reduced via biofeedback, a technique where the individual is shown bodily information that is not normally available to them (e.g., heart rate), and then taught strategies to alter this signal. This type of intervention has even shown promise in reducing heart and hypertension risk, as well as other serious conditions (Moravec, 2008; Patel et al., 1981). Reducing stress does not have to be complicated. For example, exercise is a great stress reduction activity (Salmon, 2001) that has a myriad of health benefits.

Coping Strategies: Coping is often classified into two categories: Problem-focused coping or emotion-focused coping (Carver et al., 1989). Problem-focused coping is thought of as actively addressing the event that is causing stress in an effort to solve the issue at hand. For example, say you have an important exam coming up next week. A problem-focused strategy might be to spend additional time over the weekend studying to make sure you understand all of the material. Emotion-focused coping, on the other hand, regulates the emotions that come with stress. In the above examination example, this might mean watching a funny movie to take your mind off the anxiety you are feeling. In the short term, emotion-focused coping might reduce feelings of stress, but problem-focused coping seems to have the greatest impact on mental wellness (Billings & Moos, 1981; Herman-Stabl et al., 1995). That being said, when events are uncontrollable (e.g., the death of a loved one), emotion-focused coping directed at managing your feelings, at first, might be the better strategy. Therefore, it is always important to consider the match of the stressor to the coping strategy when evaluating its plausible benefits.

Cognitive Development in Midlife (Ob 10)

Brain Functioning

The brain at midlife has been shown to not only maintain many of the abilities of young adults but also gain new ones. Some individuals in middle age actually have improved cognitive functioning (Phillips, 2011). The brain continues to demonstrate plasticity and rewires itself in middle age based on experiences. Research has demonstrated that older adults use more of their brains than younger adults. In fact, older adults who perform the best on tasks are more likely to demonstrate bilateralization than those who perform worst. Additionally, the amount of white matter in the brain, which is responsible for forming connections among neurons, increases into the 50s before it declines.

Emotionally, the middle-aged brain is calmer, less neurotic, more capable of managing emotions, and better able to negotiate social situations (Phillips, 2011). Older adults tend to focus more on positive information and less on negative information than those younger. In fact, they also remember positive images better than those younger. Additionally, the older adult’s amygdala responds less to negative stimuli. Lastly, adults in middle adulthood make better financial decisions, which seems to peak at age 53, and show better economic understanding. Although greater cognitive variability occurs among middle adults when compared to those both younger and older, those in midlife with cognitive improvements tend to be more physically, cognitively, and socially active.

Brain Health & Diet

As general health concerns increase in midlife, many people wonder how to maintain brain health and prevent cognitive decline, dementia, or illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers have investigated the connection between brain health and various lifestyle factors, including diet. The Mediterranean diet—high in fruit, vegetables, grains, and olive oil and low in red meat and processed foods—has also been associated with protecting healthy brain functioning. In particular, the brains of adults following this eating approach are less likely to exhibit the accumulation of plaques in the brain that lead to cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease (Agarwal et al., 2023).

Many aspects of the Mediterranean diet can be more affordable than less healthy food choices. For example, protein sources such as lentils and chickpeas are often cheaper than meat-based proteins. However, other food choices may be more costly, such as using olive oil instead of other sources of fat. Check out this article about more affordable ways to eat the Mediterranean way to learn what to prioritize on your shopping list.

Information processing

As we age, working memory, or our ability to simultaneously store and use information, becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). The ability to process information quickly also decreases with age. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences on many different cognitive tasks (Salthouse, 2004). Some researchers have argued that inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information, declines with age and may explain age differences in performance on cognitive tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988).

With age, systematic declines are observed on cognitive tasks requiring self-initiated, effortful processing, without the aid of supportive memory cues (Park, 2000). In middle age comment about becoming forgetful, yet this is likely due to cognitive overload associated with the responsibilities of parenting, looking after aging parents, maintaining a career, and so on (Mayo Clinic Health System, 2022). Research has not shown middle age people seem to generally function similarly to young adults in terms of memory (Salthouse, 2012).

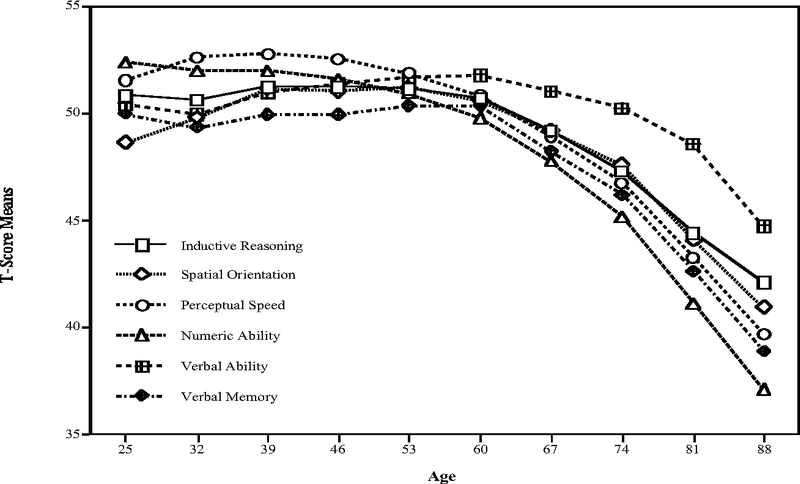

We will discuss more about memory changes in the next chapter, but we can examine memory changes through longitudinal research (tracking the same individuals over time). The Seattle Longitudinal Study has tracked the cognitive abilities of adults since 1956. Every seven years the current participants are evaluated and new individuals are also added. Approximately 6000 people have participated thus far, and 26 people from the original group are still in the study today. Current results demonstrate that middle-aged adults perform better on four out of six cognitive tasks than those same individuals did when they were young adults. Verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary increase with age until one’s 70s (Schaie, 2005; Willis & Shaie, 1999). However, numerical computation and perceptual speed decline in middle and late adulthood.

We also see that tacit knowledge and other types of practical thought skills increase with age. Tacit knowledge is pragmatic or practical and learned through experience rather than explicitly taught. It might be thought of as “know-how” or “professional instinct.” It is referred to as tacit because it cannot be codified or written down. It does not involve academic knowledge, rather it involves being able to use skills and to problem-solve in practical ways. Tacit knowledge can be understood in the workplace and by blue-collar workers such as carpenters, chefs, and hairdressers.

Plasticity of Intelligence

Prior research on cognition and aging has been focused on comparing young and old adults and assuming that midlife adults fall somewhere in between. But some abilities may decrease while others improve during midlife. The concept of plasticity means that intelligence can be shaped by experience. Intelligence is influenced by culture, social contexts, and personal choices as much as by heredity and age. In fact, there is new evidence that mental exercise or training can have lasting benefits (National Institutes of Health, 2007). We explore aspects of midlife intelligence below.

Crystalized and Fluid Intelligence

One distinction in specific intelligences noted in adulthood is between fluid intelligence, which refers to the capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities quickly and abstractly, and crystallized intelligence, which refers to the accumulated knowledge of the world, we have acquired throughout our lives (Salthouse, 2004). These intelligences are distinct, and crystallized intelligence increases with age, while fluid intelligence tends to decrease with age (Horn et al., 1981; Salthouse, 2004). There is a general acceptance that fluid intelligence decreases continually from the 20s, but that crystallized intelligence continues to accumulate.

Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities (e.g., logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time). Crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge (e.g., vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts). Crystallized intelligence includes verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary — all of which increase with age (Willis & Shaie, 1999). Research demonstrates that older adults have more crystallized intelligence as reflected in semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language. As a result, adults generally outperform younger people on measures of history, geography, and even on crossword puzzles, where this information is useful (Salthouse, 2004). It is this superior knowledge, combined with a slower and complete processing style, along with a more sophisticated understanding of the workings of the world around them, which gives older adults the advantage of “wisdom” over the advantages of fluid intelligence which favor the young (Baltes et al., 1999; Scheibe et al., 2009).

The differential changes in crystallized versus fluid intelligence help explain why older adults do not necessarily show poorer performance on tasks that also require experience or expertise (i.e., crystallized intelligence), although they show poorer memory overall. With age often comes expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform as well or better than younger individuals. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts are able to focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). A young chess player may think more quickly, for instance, but a more experienced chess player has more knowledge to draw on. Older pilots show declines in processing speed and memory capacity, but their overall performance seems to remain intact. According to Phillips (2011) researchers tested pilots age 40 to 69 as they performed on flight simulators. Older pilots took longer to learn to use the simulators, but performed better than younger pilots at avoiding collisions. Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults to make better decisions than young adults (Tentori et al., 2001).

Formal Operational Thought (Piaget revisited)

Remember formal operational thought? Formal operational thought involves being able to think abstractly; however, this ability does not apply to all situations or subjects. Formal operational thought is influenced by experience and education. Some adults lead patterned, orderly lives in which they are not challenged to think abstractly about their world. Many adults do not receive any formal education and are not taught to think abstractly about situations they have never experienced. Nor are they exposed to conceptual tools used to formally analyze hypothetical situations. Those who do think abstractly, in fact, may be able to do so more easily in some subjects than others. For example, English majors may be able to think abstractly about literature, but be unable to use abstract reasoning in physics or chemistry. Abstract reasoning in a particular field requires a knowledge base that we might not have in all areas. So, our ability to think abstractly depends to a large extent on our experiences. As discussed previously, adults tend to think in more practical terms than do adolescents. Although they may be able to use abstract reasoning when they approach a situation and consider possibilities, they are more likely to think practically about what is likely to occur.

Flow is the mental state of being completely present and fully absorbed in a task (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). When in a state of flow, the individual is able to block outside distractions and the mind are fully open to producing. Additionally, the person is achieving great joy or intellectual satisfaction from the activity and accomplishing a goal. Further, when in a state of flow, the individual is not concerned with extrinsic rewards. Csikszentmihalyi (1996) used his theory of flow to research how some people exhibit high levels of creativity as he believed that a state of flow is an important factor in creativity (Kaufman & Gregoire, 2016). Other characteristics of creative people identified by Csikszentmihalyi (1996) include curiosity and drive value for intellectual endeavors, and an ability to lose our sense of self and feel a part of something greater. In addition, he believed that the tortured creative person was a myth and that creative people were very happy with their lives. According to Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2002) people describe flow as the height of enjoyment. The more they experience it, the more they judge their lives to be gratifying. The qualities that allow for flow are well-developed in middle adulthood.

Learning in Older Adults (Ob 11)

Midlife adults in the United States often find themselves in classrooms. Whether they enroll in school to sharpen particular skills, to retool and reenter the workplace, or to pursue interests that have previously been neglected, these students tend to approach teach differently than do younger college students (Knowles et al., 1998).

The mechanics of cognition, such as working memory and speed of processing, gradually decline with age. However, they can be easily compensated for through the use of higher-order cognitive skills, such as forming strategies to enhance memory or summarizing and comparing ideas rather than relying on rote memorization (Lachman, 2004). An 18-year-old college student may focus more on rote memorization in studying for tests. They may be able to memorize information more quickly than an older student, but not have as thorough a grasp on the meaning of that information. Older students may take a bit longer to learn the material, but are less likely to forget it quickly. Adult learners tend to look for relevance and meaning when learning information. Older adults have the hardest time learning material that is meaningless or unfamiliar. They are more likely to ask themselves, “What does this mean?” or “Why is this important?” when being introduced to information or when trying to concepts or facts. Older adults are more task-oriented learners and want to organize their activity around problem-solving. They see the instructor as a resource person rather than the “expert” and appreciate having their life experience recognized and incorporated into the material being covered. This type of learning is more easily accomplished if adequate time is allowed for mastering the material. Keeping distractions at a minimum and studying when rested and energetic enhances adult learning.

To address the educational needs of those over 50, The American Association of Community Colleges (2016) developed the Plus 50 Initiative that assists community college in creating or expanding programs that focus on workforce training and new careers for the plus-50 population. Since 2008 the program has provided grants for programs to 138 community colleges affecting over 37, 000 students. The participating colleges offer workforce training programs that prepare 50 plus adults for careers in such fields as early childhood educators, certified nursing assistants, substance abuse counselors, adult basic education instructors, and human resources specialists. These training programs are especially beneficial as 80% of people over the age of 50 say they will retire later in life than their parents or continue to work in retirement, including in a new field.

Gaining Expertise: The Novice and the Expert (Ob 9)

We discussed the benefits of expertise with age and now we will discuss more about expert thought. When we work extensively in an area, we may gain expertise. Consider the study skills of a seasoned student versus a new student or a new nurse versus an experienced nurse. One of the major differences is that the new one operates as a novice while the seasoned student or nurse performs more like an expert. An expert has a different approach to learning and problem-solving than does a novice or someone new to a field. While a novice tends to rely on formal procedures or guidelines, the expert relies more on intuition and is more flexible in solving problems. A novice’s performance tends to be more conscious and methodical than experts. An expert tends to perform actions in a more automatic fashion. An expert cook, for example, may be able to prepare a difficult recipe but not really describe how they did it. The novice cook might rigidly adhere to the recipe, hanging on every word and measurement. The expert also has better strategies for tackling problems than does a novice.

Expertise refers to specialized skills and knowledge that pertain to a particular topic or activity. In contrast, a novice is someone who has limited experiences with a particular task. Everyone develops some level of “selective” expertise in things that are personally meaningful to them, such as making bread, quilting, computer programming, or diagnosing illness. Expert thought is often characterized as intuitive, automatic, strategic, and flexible.

- Intuitive: Novices follow particular steps and rules when problem-solving, whereas experts can call upon a vast amount of knowledge and past experience. As a result, their actions appear more intuitive than formulaic. A novice cook may slavishly follow the recipe step by step, while a chef may glance at recipes for ideas and then follow her own procedure.

- Automatic: Complex thoughts and actions become more routine for experts. Their reactions appear instinctive over time, and this is because expertise allows us to process information faster and more effectively (Crawford & Channon, 2002).

- Strategic: Experts have more effective strategies than non-experts. For instance, while both skilled and novice doctors generate several hypotheses within minutes of an encounter with a patient, the more skilled clinicians’ conclusions are likely to be more accurate. In other words, they generate better hypotheses than the novice. This is because they are able to discount misleading symptoms and other distractors and hone in on the most likely problem the patient is experiencing (Norman, 2005).

- Flexible: Experts in all fields are more curious and creative; they enjoy a challenge and experiment with new ideas or procedures. The only way for experts to grow in their knowledge is to take on more challenging, rather than routine tasks.

Expertise takes time. It is a long process resulting from experience and practice (Ericsson et al., 2006). Middle-aged adults, with their store of knowledge and experience, are likely to find that when faced with a problem they have likely faced something similar before. This allows them to ignore the irrelevant and focus on the important aspects of the issue. Expertise is one reason why many people often reach the top of their career in middle adulthood. However, expertise cannot fully make-up for all losses in general cognitive functioning as we age. The superior performance of older adults in comparison to younger novices appears to be task specific (Charness & Krampe, 2006). As we age, we also need to be more deliberate in our practice of skills in order to maintain them. Charness and Krampe (2006) in their review of the literature on aging and expertise, also note that the rate of return for our effort diminishes as we age. In other words, increasing practice does not recoup the same advances in older adults as similar efforts do at younger ages.

Psychosocial Development during Midlife

What do you think is the happiest stage of life? What about the saddest stages? Perhaps surprisingly, Blanchflower & Oswald (2008) found that reported levels of unhappiness and depressive symptoms peak in the early 50s for men in the U.S., and interestingly, the late 30s for women. In Western Europe, minimum happiness is reported around the mid 40s for both men and women, albeit with some significant national differences. Stone et al. (2017) reported a precipitous drop in perceived stress in men in the U.S. from their early 50s. There is now a view that “older people” (50+) may be “happier” than younger people, despite some cognitive and functional losses. This is often referred to as “the paradox of aging.” Positive attitudes to the continuance of cognitive and behavioral activities, interpersonal engagement, and their vitalizing effect on human neural plasticity, may lead not only to more life, but to an extended period of both self-satisfaction and continued communal engagement.

Midlife crisis? (Ob 10)

Remember Levinson’s theory from the last chapter? Levinson found that the men he interviewed sometimes had difficulty reconciling the “dream” they held about the future with the reality they now experience. “What do I really get from and give to my wife, children, friends, work, community-and self?” a man might ask (Levinson, 1978, p. 192). Tasks of the midlife transition include 1) ending early adulthood; 2) reassessing life in the present and making modifications if needed, and 3) reconciling “polarities” or contradictions in one’s sense of self. Perhaps, early adulthood ends when a person no longer seeks adult status but feels like a full adult in the eyes of others. This ‘permission’ may lead to different choices in life; choices that are made for self-fulfillment instead of social acceptance. While people in their early 20s may emphasize how old they are (to gain respect, to be viewed as experienced), by the time people reach their 40s, they tend to emphasize how young they are. (Few 40-year-olds cut each other down for being so young: “You’re only 43? I’m 48!!”)