Chapter 2: Developmental Theories

Objectives:

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to…

- Define theory.

- List key considerations for lifespan theories.

- Describe Freud’s theory of development including parts of self (id, ego, superego).

- Appraise the strengths and weaknesses of Freud’s theory.

- List and apply Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development to examples of people in various stages of the lifespan.

- Appraise the strengths and weaknesses of Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development.

- Describe the principles of classical conditioning including unconditioned stimulus, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response.

- Describe the principles of operant conditioning including punishment and reinforcement.

- Describe social learning theory.

- Describe Piaget’s theory of cognitive development including schema, assimilation, and accommodation.

- Describe Piaget’s stages of cognitive development.

- Describe Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development including the zone of proximal development, guided participation, and scaffolding.

- Describe the information processing model of cognitive development.

- Describe Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model.

- Describe key current models for understanding development.

The objectives are indicated by the reading sections below.

Introduction

In this chapter, we will start to examine theories of human development. As discussed in chapter one, human development describes the growth throughout their lifespan, from conception to death. Psychologists strive to understand and explain how and why people change throughout life. We will see that different theories cover different aspects of growth — like how we think, process and remember information changes across the lifespan. Much of what is covered in developmental theory is what expected, typical growth is. Some of the theories presented in this chapter are considered classic theories that have now been debated. They are still taught for historical purposes, and each holds important underlying concepts to understanding others. We will first cover the basics of what a theory is and then review several major theories in human development.

What is a theory? (Ob 1)

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories . . .” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. However, theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior; in fact, they are proposed explanations for the “how” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3-year-old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other objects that required assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more quickly than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which several single cases are observed, and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist develops ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them.

Theoretical Considerations for Lifespan Development Theories (Ob 2)

At the heart of all of these developmental theories are two main questions: (1) How do nature and nurture interact in development? (2) Does development progress through qualitatively distinct stages? In the remainder of this chapter, we examine the answers that are emerging regarding these questions

Nature and Nurture: Why are you the way you are? As you consider some of your features (height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc.), ask yourself whether these features are a result of heredity or environmental factors, or both. Chances are, you can see how both heredity and environmental factors (such as lifestyle, diet, and so on) have contributed to these features. Nature refers to our biological endowment, the genes we receive from our parents. Nurture refers to the environments, social, as well as physical that influence our development, everything from the womb in which we develop before birth to the homes in which we grow up, the schools we attend, and the many people with whom we interact. Most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

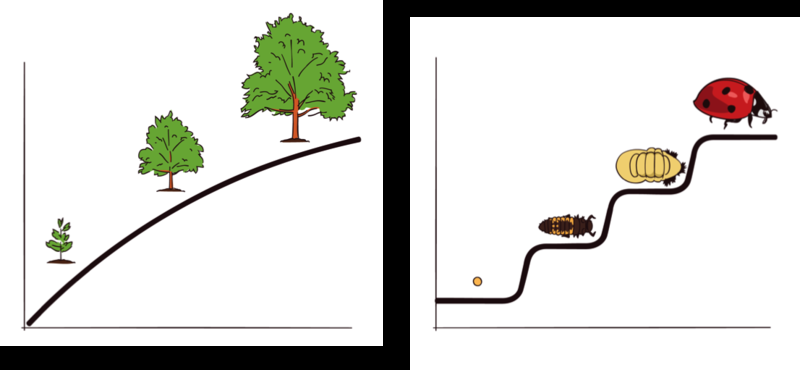

Continuity versus Discontinuity: Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The classical theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories, which emphasize discontinuous development, assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. An example of this is in the figure below with the different stages of development for a ladybug or consider the lifecycle of a butterfly. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume that development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development (non-stage theories see development as continuous). For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more advanced skills.

Active versus Passive: How much do you play a role in your developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their development. For example, Piaget, the classical stage theorist for cognitive development, believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. If you have an active view of development you would see the individual as more in control with surroundings (choosing toy, activity, extra curricular activities, and friends to play with). In contrast, many behaviorists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process. A passive view sees individuals as having less control with behaviors. One might see development as more a product of the environment or social influences or due to biological changes.

Why do we do what we do? Exploring Motivation

Freud’s Psychodynamic Theory (Ob 2)

We begin with the often-controversial figure, Sigmund Freud. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was a Viennese M. D. who was trained in neurology and asked to work with patients suffering from hysteria, a condition marked by uncontrollable emotional outbursts, fears, and anxiety that had puzzled physicians for centuries. Freud began working with hysterical patients and discovered that when they began to talk about some of their life experiences, particularly those that took place in early childhood, their symptoms disappeared. This led him to suggest the first purely psychological explanation for physical problems and mental illness. What he proposed was that unconscious motives and desires, fears, and anxieties drive our actions.

Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that how parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resiliency in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady & Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development. At the conclusion of this section on Freud we will identify the worthwhile contributions of his work.

Theory of the mind

Freud believed that most of our mental processes, motivations, and desires are outside of our awareness. Our consciousness, that of which we are aware, represents only the tip of the iceberg that comprises our mental state. The preconscious represents that which can easily be called into the conscious mind. During development, our motivations and desires are gradually pushed into the unconscious because raw desires are often unacceptable in society.

Theory of the self (Ob 3)

According to Freud's theory of the self, as adults, our personality or self consists of three main parts: the id, the ego, and the superego. The Id is the part of the self with which we are born. It consists of the biologically-driven self and includes our instincts and drives. It is the part of us that wants immediate gratification. Later in life, it comes to house our deepest, often unacceptable desires such as sex and aggression. It operates under the pleasure principle which means that the criteria for determining whether something is good or bad is whether it feels good or bad. According to Freud, an infant is all Id. The ego is the part of the self that develops as we learn that there are limits on what is acceptable to do and that often, we must wait to have our needs satisfied. This part of the self is realistic and reasonable. It knows how to make compromises. It operates under the reality principle or the recognition that sometimes need gratification must be postponed for practical reasons. It acts as a mediator between the Id and the Superego and is viewed as the healthiest part of the self.

If the ego is strong, the individual is realistic and accepting of reality and remains more logical, objective, and reasonable. Building ego strength is an important goal of psychoanalysis (Freudian psychotherapy). So, for Freud, having a big ego is a good thing because it does not refer to being arrogant; it refers to being able to accept reality.

The superego is the part of the self that develops as we learn the rules, standards, and values of society. This part of the self considers the ethical guidelines that are a part of our culture. It is a rule-governed part of the self that operates under a sense of guilt (guilt is a social emotion-it is a feeling that others think less of you or believe you to be wrong). If a person violates the superego, he or she feels guilty. The superego is useful but can be too strong; in this case, a person might feel overly anxious and guilty about circumstances over which they had no control. Such a person may experience high levels of stress and inhibition that keeps them from living well. The id is inborn, but the ego and superego develop during our first interactions with others. These interactions occur against a backdrop of learning to resolve new biological and social challenges and play a key role in our personality development.

Freud is also known for explaining defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms emerge to help a person distort reality so that the truth is less painful because we feel threatened, or because our id or superego becomes too demanding. Defense mechanisms include repression which means to push the painful thoughts out of consciousness (in other words, think about something else). Denial is not accepting the truth or lying to the self. Thoughts such as “it won’t happen to me” or “you’re not leaving” or “I don’t have a problem with alcohol” are examples. Sublimation involves transforming unacceptable urges into more socially acceptable behaviors. For example, a teenager who experiences strong sexual urges uses exercise to redirect those urges into more socially acceptable behavior. Displacement involves taking out frustrations onto a safer target. A person who is angry at a boss may take out their frustration at others when driving home or at a spouse upon arrival. Projection is a defense mechanism in which a person attributes their unacceptable thoughts onto others. If someone is frightened, for example, he or she accuses someone else of being afraid. This is a partial listing of defense mechanisms suggested by Freud.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory (Ob 4)

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is challenging to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which elaborates and modifies subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views. Now, let’s turn to a less controversial psychodynamic theorist, the father of developmental psychology, Erik Erikson.

Erikson and Psychosocial Theory (Ob 5)

The Ego Rules (Ob 5, Ob 6)

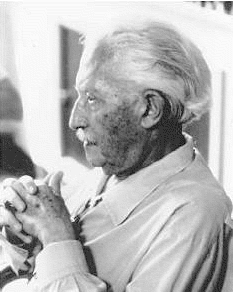

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) was a student of Freud’s and expanded on his theory by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968). He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the Id. We make conscious choices in life, and these choices focus on meeting specific social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems. Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages forming a psychosocial stage theory of development. In each stage, we have a primary psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living.

Psychosocial Stages

Erikson's psychosocial theory has 8 stages. We will discuss each of these stages in length as we explore each period of the life span, but here is a brief overview:

- Trust vs. mistrust (0-1 years old/infancy): the infant must have basic needs met consistently in order to feel that the world is a trustworthy place

- Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1-2 years old/toddlerhood): mobile toddlers have newfound freedom they like to exercise, and by being allowed to do so, they learn some basic independence

- Initiative vs. Guilt (3-5 years old/early childhood): preschoolers like to initiate activities and emphasize doing things “all by myself”

- Industry vs. inferiority (6-11 years old/middle childhood): school-aged children focus on accomplishments and begin making comparisons between themselves and their classmates

- Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence): teenagers are trying to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas

- Intimacy vs. Isolation (young/early adulthood): in our 20s and 30s we are making some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships

- Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood): the 40s through the early 60s we focus on being productive at work and home and are motivated by wanting to feel that we’ve contributed to society

- Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood): we look back on our lives and hope to like what we see, that we have lived well and have a sense of integrity because we lived according to our beliefs.

Table. Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development across the Lifespan

| Age Period | Psychosocial Stage | Main Developmental Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Infancy | Trust vs. mistrust | Establish a bond with a trusted caregiver |

| Toddlerhood | Autonomy vs. shame and doubt | Develop a healthy sense of self as distinct from others |

| Early Childhood | Initiative vs. Guilt | Initiate activities in a purposeful way |

| Middle Childhood | Industry vs. Inferiority | Begin to learn knowledge and skills of culture |

| Adolescence | Identity vs. identity confusion | Develop a secure and coherent identity |

| Early Adulthood | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish a committed, long-term love relationship |

| Middle Adulthood | Generativity vs. stagnation | Care for others and contribute to the well-being of the young |

| Late Adulthood | Ego integrity vs. despair | Evaluate lifetime, accept it as it is |

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

How Do We Act? Exploring Behavior

Learning theories focus on how we respond to events or stimuli rather than emphasizing what motivates our actions. These theories explain how experience can change what we are capable of doing or feeling.

Classical Conditioning and Emotional Responses (Ob 7)

Classical Conditioning theory helps us to understand how our responses to one situation become attached to new situations. For example, a smell might remind us of a time when we were a kid (elementary school cafeterias smell like milk and mildew!). If you went to a new cafeteria with the same smell, it might evoke feelings you had when you were in school. Or a song on the radio might remind you of a memorable evening you spent with your first true love. Or, if you hear your entire name (John Wilmington Brewer, for instance) called as you walk across the stage to get your diploma and it makes you tense because it reminds you of how your father used to use your full name when he was mad at you, you’ve been classically conditioned!

Classical conditioning explains how we develop many of our emotional responses to people or events or our “gut level” reactions to situations. New situations may bring about an old response because the two have become connected. Attachments form in this way. Addictions are affected by classical conditioning, as anyone who has tried to quit smoking can tell you. When you try to quit, everything that was associated with smoking makes you crave a cigarette.

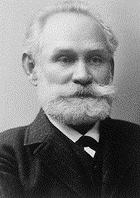

Pavlov (Ob 7, Ob 8)

Ivan Pavlov (1880-1937) first studied classical conditioning. He was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to salivate when the food hit their palate automatically, but BEFORE the food comes? Of course, what had happened was . . . you tell me. That’s right! The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The key word here is “learned.” A learned response is called a conditioned response. Pavlov began to experiment with this “psychic” reflex. He began to ring a bell, for instance, before introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon (conditioned response). Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned stimulus), and one is learned (conditioned stimulus).

Pavlov’s classical conditioning

Table. Process of Classical Conditioning

| start US → UR |

The stimulus (S) is naturally paired with a response (R). Both have U for unconditioned (not learned). |

| Training/conditioning N/CS + US → UR |

A new stimulus (N/CS) is introduced before the original pairing. This is repeated until the new stimulus becomes conditioned (CS). |

| conditioned CS → CR |

After repeated pairings, the once new stimulus becomes conditioned and now produces the original response. |

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. Another example you are probably very familiar with involves your alarm clock. If you are like most people, waking up early usually makes you unhappy. In this case, waking up early (US) produces a natural sensation of grumpiness (UR). Rather than waking up early on your own, though, you likely have an alarm clock that plays a tone to wake you. Before setting your alarm to that particular tone, let’s imagine you had neutral feelings about it (i.e., the tone had no prior meaning for you). However, now that you use it to wake up every morning, you psychologically “pair” that tone (CS) with your feelings of grumpiness in the morning (UR). After enough pairings, this tone (CS) will automatically produce your natural response of grumpiness (CR). Thus, this linkage between the unconditioned stimulus (US; waking up early) and the conditioned stimulus (CS; the tone) is so strong that the unconditioned response (UR; being grumpy) will become a conditioned response (CR; e.g., hearing the tone at any point in the day—whether waking up or walking down the street—will make you grumpy). Modern studies of classical conditioning use a vast range of CS’s and US’s and measure a wide range of conditioned responses.

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. Did you know emotions and fears can be classically conditions? One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. Did you know emotions and fears can be classically conditions? One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.

Watson and Behaviorism (Ob 7)

Watson believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public. He believed that parents could be taught to help shape their children’s behavior and tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert.” Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. However, Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises, so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and magazines and gained much popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order. Parenting advice was not the legacy Watson left us, however. Where he made his impact was in advertising. After Watson left academia, he went into the world of business and showed companies how to tie something that brings about a natural positive feeling to their products to enhance sales. Thus, the union of sex and advertising!

Operant Conditioning and Repeating Actions (Ob 8)

Operant Conditioning is another learning theory that emphasizes a more conscious type of learning than that of classical conditioning. A person (or animal) does something (operates something) to see what effect it might bring. Simply said, operant conditioning describes how we repeat behaviors because they pay off for us. It is based on a principle authored by a psychologist named Thorndike (1874-1949) called the law of effect. The law of effect suggests that we will repeat an action if a good effect follows it. However, when a behavior has a negative (painful/annoying) consequence, it is less likely to be repeated in the future. Effects that increase behaviors are referred to as reinforcers, and effects that decrease them are referred to as punishers. Operant conditioning occurs when a behavior (as opposed to a stimulus) is associated with the occurrence of a significant event. This voluntary behavior is called an operant behavior, because it “operates” on the environment (i.e., it is an action that the animal itself makes).

Let’s think about how operant conditioning is used on us. Have you ever done something to get a reward or not done something to avoid punishment? This is operant conditioning!

Skinner and Reinforcement (Ob 8)

B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) continued the expand on Thorndike’s principle and outlined the principles of operant conditioning. Skinner believed that we learn best when our actions are reinforced. For example, a child who cleans his room and is reinforced (rewarded) with a big hug and words of praise is more likely to clean it again than a child whose deed goes unnoticed. Skinner believed that almost anything could be reinforcing. A reinforcer is anything following a behavior that makes it more likely to occur again. It can be something intrinsically rewarding (called intrinsic or primary reinforcers), such as food or praise, or it can be something rewarding because it can be exchanged for what one wants (such as using money to buy a cookie). Such reinforcers are referred to as secondary reinforcers or extrinsic reinforcers.

Positive and negative reinforcement (Ob 8)

Sometimes, adding something to the situation is reinforcing as in the cases we described above with cookies, praise, and money. Positive reinforcement involves adding something to the situation in order to encourage a behavior. Other times, taking something away from a situation can be reinforcing. For example, the loud, annoying buzzer on your alarm clock encourages you to get up so that you can turn it off and get rid of the noise. Children whine in order to get their parents to do something and often, parents give in to stop the whining. In these instances, negative reinforcement has been used.

Operant conditioning tends to work best if you focus on trying to encourage a behavior or move a person into the direction you want them to go rather than telling them what not to do. Reinforcers are used to encourage behavior; punishers are used to stop a behavior. A punisher is anything that follows an act and decreases the chance it will reoccur. However, often a punished behavior does not go away. It is just suppressed and may reoccur whenever the threat of punishment is removed. For example, a child may not cuss around you because you have washed his mouth out with soap, but he may cuss around his friends. Alternatively, a motorist may only slow down when the trooper is on the side of the freeway. Another problem with punishment is that when a person focuses on punishment, they may find it hard to see what the other does right or well. Moreover, the punishment is stigmatizing; when punished, some start to see themselves as bad and give up trying to change.

Table. Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Punishment

| Positive (+) ADD | Negative (-) REMOVE | |

|---|---|---|

| Reinforcement (increase behavior that follows it) | Positive Reinforcement (pleasant consequence to reward)

Example: dog gets treat for doing trick |

Negative Reinforcement (remove aversive stimulus to reward)

Example: buckle up to avoid car seat alarm |

| Punishment (decrease behavior) | Positive Punishment (add aversive stimulus to punish)

Example: pay fine for late library book |

Negative Punishment (remove pleasant stimuli to punish)Example: Taken out of game for rough behavior |

Reinforcement can occur in a predictable way, such as after every desired action is performed, or intermittently after the behavior is performed a number of times or the first time it is performed after a certain amount of time. The schedule of reinforcement has an impact on how long a behavior continues after reinforcement is discontinued. So, a parent who has rewarded a child’s actions each time may find that the child gives up very quickly if a reward is not immediately forthcoming. A lover who is warmly regarded now and then may continue to seek out his or her partner’s attention long after the partner has tried to break up. Think about the kinds of behaviors you may have learned through classical and operant conditioning. You may have learned many things in this way. However, sometimes we learn very complex behaviors quickly and without direct reinforcement. Bandura explains how.

Social Learning Theory (Ob 9)

Albert Bandura is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to how many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; instead, they are learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation. Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by modeling or copying the behavior of others. An employee on his or her first day of a new job might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Newly married couples often rely on roles they may have learned from their parents and begin to act in ways they did not while dating and then wonder why their relationship has changed. Sometimes we do things because we have seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura et al., 1963).

![]() Let’s think about social learning theory. Do parents socialize children or do children socialize parents?

Let’s think about social learning theory. Do parents socialize children or do children socialize parents?

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is an interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings; rather we influence our surroundings. There is interplay between our personality and the way we interpret events and how they influence us. This concept is called reciprocal determinism.

An example of this might be the interplay between parents and children. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently to their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us, and we create our environment. Other social influences: TV or not TV? (Bandura et al., 1963) began a series of studies to look at the impact of television, particularly commercials, have on the behavior of children. Are children more likely to act out aggressively when they see this behavior modeled? What if they see it being reinforced? Bandura began by conducting an experiment in which he showed children a film of a woman hitting an inflatable clown or “Bobo” doll. Then the children were allowed in the room where they found the doll and immediately began to hit it. This was without any reinforcement whatsoever. Later they viewed a woman hitting a real clown, and sure enough, when allowed in the room, they too began to hit the clown! Not only that, but they found new ways to behave aggressively. It is as if they learned an aggressive role.

Children view far more television today than in the 1960s; so much, in fact, that they have been referred to as Generation M (media). Based on a study of a national representative sample of over 7,000 8 to 18-year-olds, the Kaiser Foundation (2010) reports that children spend just over 7 hours a day involved with media outside of schoolwork. This includes almost 4 hours of television viewing and over an hour on the computer. Two-thirds have a television in their room, and those children watch an average of 1.27 hours more of television per day than those that do not have a television in their bedroom (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005). The prevalence of violence, sexual content, and messages promoting foods high in fat and sugar in the media are certainly cause for concern and the subjects of ongoing research and policy review. Many children spend even more time on the computer viewing content from the internet. Moreover, the amount of time spent connected to the internet continues to increase with the use of smartphones that primarily serve as mini-computers. What are the implications of this?

Children view far more television today than in the 1960s; so much, in fact, that they have been referred to as Generation M (media). Based on a study of a national representative sample of over 7,000 8 to 18-year-olds, the Kaiser Foundation (2010) reports that children spend just over 7 hours a day involved with media outside of schoolwork. This includes almost 4 hours of television viewing and over an hour on the computer. Two-thirds have a television in their room, and those children watch an average of 1.27 hours more of television per day than those that do not have a television in their bedroom (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005). The prevalence of violence, sexual content, and messages promoting foods high in fat and sugar in the media are certainly cause for concern and the subjects of ongoing research and policy review. Many children spend even more time on the computer viewing content from the internet. Moreover, the amount of time spent connected to the internet continues to increase with the use of smartphones that primarily serve as mini-computers. What are the implications of this?

What do we think? Exploring Cognition

Cognitive theories focus on how our mental processes or cognitions change over time. We will examine the ideas of two cognitive theorists: Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky.

Piaget: Changes in thought with maturation (Ob 10)

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists in development inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out how children’s intelligence differs from that of adults. He became interested in this area when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers! He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time and that maturation rather than training brings about that change. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Making sense of the world (Ob 10)

Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain cognitive equilibrium or a balance or cohesiveness in what we see and what we know. Children have much more of a challenge in maintaining this balance because they are continually being confronted with new situations, new words, new objects, etc. When faced with something new, a child may either fit it into an existing framework (schema) and match it with something known (assimilation) such as calling all animals with four legs “doggies” because he or she knows the word doggie, or expand the framework of knowledge to accommodate the new situation (accommodation) by learning a new word to more accurately name the animal. This is the underlying dynamic in our cognition. Even as adults we continue to try and “make sense” of new situations by determining whether they fit into our old way of thinking or whether we need to modify our thoughts.

![]() If a child saw a moth but said it was a butterfly, did the child assimilate or accommodate? If a child saw an ant and said bug, did the child assimilate or accommodate?

If a child saw a moth but said it was a butterfly, did the child assimilate or accommodate? If a child saw an ant and said bug, did the child assimilate or accommodate?

Stages of Cognitive Development (Ob 11)

Piaget outlined four major stages of cognitive development. Let me briefly mention them here, but we will discuss them in detail throughout the course. For about the first two years of life, the child experiences the world primarily through their senses and motor skills. Piaget referred to this type of intelligence as sensorimotor intelligence. During the preschool years, the child begins to master the use of symbols or words and can think of the world symbolically but not yet logically. This stage is the preoperational stage of development. The concrete operational stage in middle childhood is marked by an ability to use logic in understanding the physical world. In the final stage, the formal operational stage the adolescent learns to think abstractly and to use logic in both concrete and abstract ways.

Table. Piaget’s Stage Theory of Cognitive Development

| Typical Age Range | Stage – descriptor |

| Birth to ~ 2 years | Sensorimotor – learning through senses and actions/motor skills (touch, look, put in mouth, grasp, etc.) |

| 2 to ~ 6-7 years | Preoperational – using symbols (language, imaginative play), lack logical reasoning |

| ~7 to 11 years | Operational – logical thought for concrete events, understanding categories, hierarchies and arithmetic operations |

| ~ 12 to adulthood | Formal Operational – abstract reasoning |

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory (Ob 11)

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) plays in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children can do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances. For example, we will learn more about more current research examining infant cognition and babies’ understanding of the world in chapter 3.

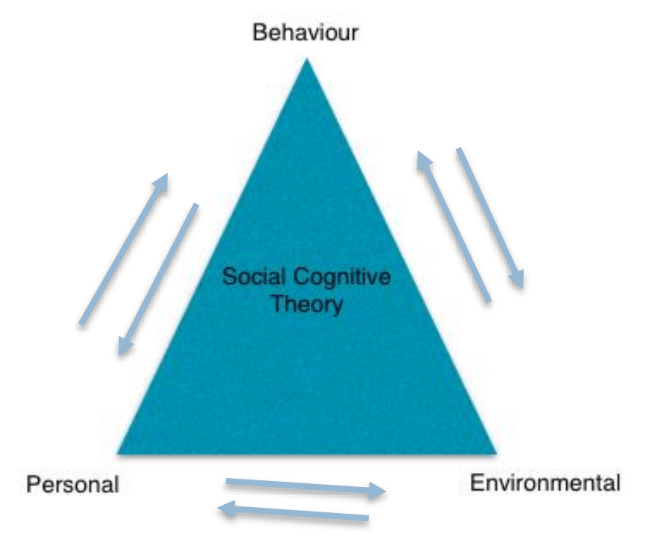

Vygotsky: Changes in thought with guidance (Ob 12)

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person has not only a set of abilities but also a set of inherent abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation, also known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child could learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development. Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You assisted them when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. The individual learning that needs more guidance or scaffolding has a larger zone of proximal development (more room for growth in learning the task or skill independently). Someone who already can do the task or skill with little help is said to have a smaller zone of proximal development (needs less scaffolding). This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern day educators. We will discuss Vygotsky in greater depth in upcoming lessons.

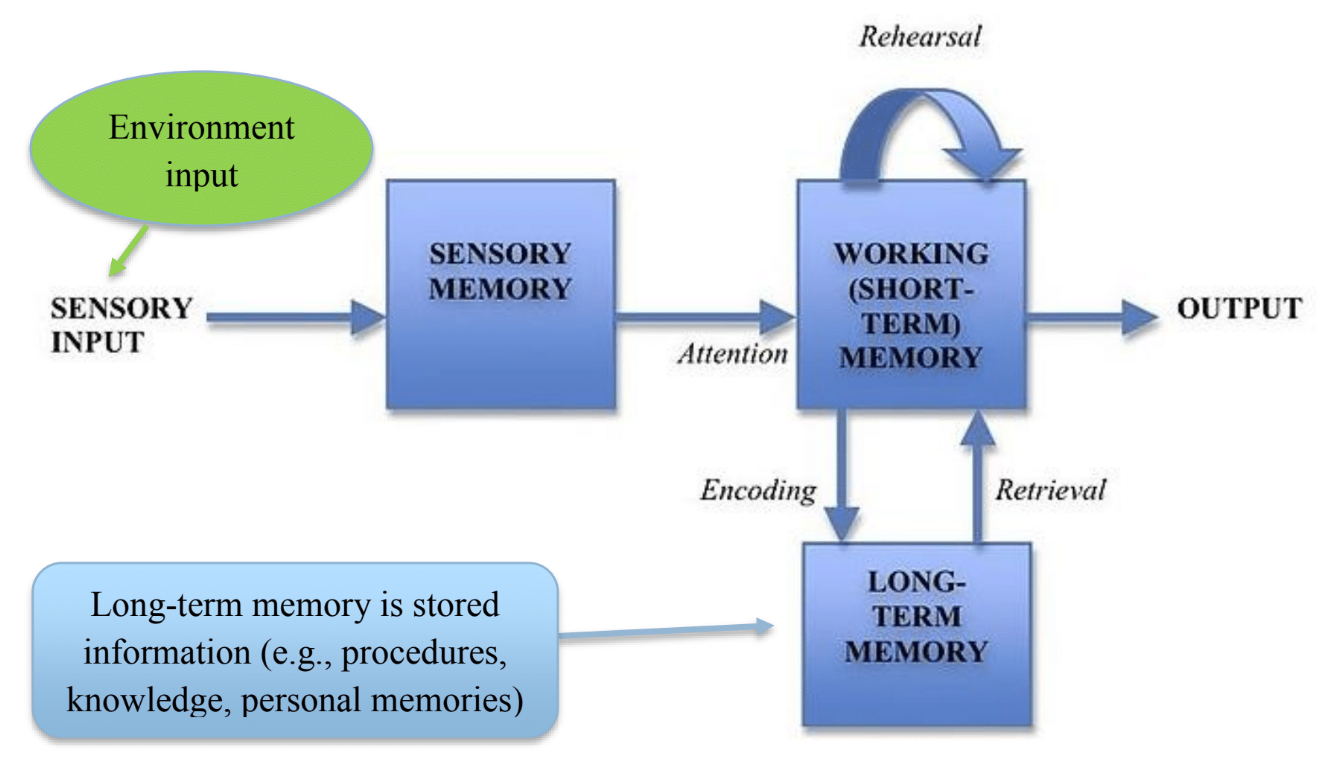

Information Processing is not the work of a single theorist, but based on the ideas and research of several cognitive scientists studying how individuals perceive, analyze, manipulate, use, and remember information. The information processing model theorizes that information made available by the environment is processed by a series of processing systems (e.g. attention, perception, aspects of memory). This approach assumes that humans gradually improve in their processing skills; that is, development is continuous rather than stage-like. The information processing model is analogous to computer functioning in that we combine information presented with stored information like you are able to as you edit and resave files on a computer. However, humans do have limitations in how well we process information and we may not recall or restore information as efficiently as a computer. Additionally, humans are not serial processors and are more complex than computers (for example, consider our emotional and motivational factors).

The image below shows a version of the information processing model. The processors that are shown (sensory memory, working (short-term) memory, long term memory) are used as we attend, store, and retrieve information. We first notice stimuli through our senses and then we begin to process information in our working (short-term) memory. Once memory has been stored, it is in our long-term memories. Working (short-term) memory has a limited capacity. We first notice stimuli through our senses and then we begin to process information in our working (short-term) memory. Once memory has been stored, it is in our long-term memories.

Information processing theories see the more complex mental skills of adults being built from the primitive abilities of children in a continuously developing process. We are born with the ability to notice stimuli, store, and retrieve information. Brain maturation enables advancements in our information processing system. At the same time, interactions with the environment also aid in our development of more effective strategies for processing information.

Putting it all together: Ecological Systems Model (Ob 14)

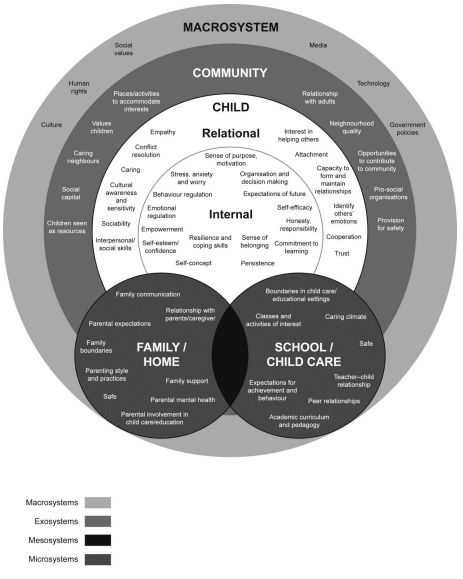

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) provides a model of human development, the ecological systems model, that addresses its many influences. Bronfenbrenner recognized that larger social forces influence human interaction and that an understanding of those forces is essential for understanding an individual.

- Microsystem includes the individual’s setting and those who have direct, significant contact with the person, such as parents or siblings. The input of those is modified by the cognitive and biological state of the individual as well. These influence the person’s actions, which in turn influence systems operating on him or her.

- Mesosystem consists of the interactions between the different parts of microsystem of person. These could include interactions between the microsystems, such as the interaction between different family members and individual’s within organizational structures, such as school, the family, or religion (e.g., parent and teacher, .

- Exosystem includes the broader contexts of the community. A community’s values, history, and economy can impact the organizational structures it houses. Mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the exosystem.

- Macrosystem includes cultural elements, such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and society’s responses to the global community.

- Chronosystem is the historical context in which these experiences occur. This relates to the different generational periods previously discussed such as the baby boomers and millennials.

Watch this short video for a brief explanation and history of Brofenbrenner’s theory (Sprouts, 2021).

In sum, a child’s experiences are shaped by larger forces such as the family, schools, and religion, and culture. All of this occurs in a historical context or chronosystem. Bronfenbrenner’s model helps us combine each of the other theories described above and gives us a perspective that brings it all together. Despite its comprehensiveness, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory is not easy to use. Taking into consideration all the different influences makes it difficult to research and determine the impact of all the different variables (Dixon, 2003). Consequently, psychologists have not fully adopted this approach, although they recognize the importance of the ecology of the individual. The figure below is an expanded version of Brofenbrenner’s model including examples for each system.

Current theoretical considerations (Ob 15)

The field of developmental psychology has evolved significantly since the foundational theories such as Piaget, Vygotsky, and Erikson were first introduced. While these classic theories continue to provide valuable insights, contemporary approaches have expanded our understanding of human development in important ways. As research methods and technologies have advanced, newer theories emphasize the complex, dynamic nature of development across the lifespan. Three key contemporary approaches are dynamic systems theory, neurodevelopmental theories, and epigenetics. These modern perspectives build on the groundwork laid by earlier theorists while incorporating new findings about the intricate interplay between biology, experience, and environment in shaping development.

Dynamic systems theory: views development as an ongoing process of complex interactions between multiple components, rather than a predetermined, linear progression. This theory offers a more flexible and comprehensive view of development than traditional stage theories. The theory emphasizes that development can vary significantly between individuals, skills and behaviors might appear, disappear, and reappear during development. Also, interventions that focus on one area (e.g., nutrition) can have greater effect on development (e.g., cognitive benefits of changes in nutrition).

Neurodevelopmental theories: integrate findings from neuroscience to understand how brain development relates to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral growth. Neurodevelopmental theories provide a framework for understanding how the brain and nervous system develop and influence behavior, cognition, and emotions throughout childhood and adolescence. This framework takes into account brain development timing, sensitive periods for acquiring specific skills (e.g., language exposure for language development, brain plasticity, and gene-environment interactions.

Epigenetics specifically focus on gene-environment interactions. Epigenetics bridges the gap between nature and nurture in developmental psychology. Epigenetics examines how environmental factors can influence gene expression and, consequently, developmental outcomes. Epigenetics plays a role in gene expression. Epigenetics controls which genes are active (expressed) or inactive (silenced) in different cells and at different times (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010). Epigenetics changes can also be reversed (unlike genetic changes). Factors like diet, stress, and exposure to toxins can trigger epigenetic changes (NSCDC, 2010). Epigenetics helps explain how early life experiences can have long-lasting effects on development and behavior (NSCDC, 2010).

Watch this from Penn State for a brief explanation about epigenetics (Penn Medicine, 2021).

All three of these contemporary share some common themes that distinguish them from classic stage theories: They emphasize continuous, multidirectional change rather than discrete stages. They recognize development as a product of interactions between multiple levels of organization, from genes to culture. Finally, they highlight the importance of both stability and plasticity in developmental processes.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided a foundational overview of the major theories that have shaped our understanding of human development. From Freud’s psychoanalytic perspective on the unconscious forces driving behavior to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model encompassing the multifaceted influences on the individual, we’ve seen how these theories offer unique lenses through which to understand the complexities of human growth.

Keep in mind that these theories are not competing for a single “truth” about development. Rather, they each offer valuable insights into different facets of the human experience, highlighting the interplay of biological, cognitive, social, and emotional factors across the lifespan. As you delve deeper into the study of human development, remember to consider these diverse perspectives and how they can inform your understanding of the intricate processes that shape who we are and how we change over time.

Moving forward, we’ll explore these theories in greater depth, examining their applications to specific developmental stages and challenges. By integrating these theoretical frameworks with empirical research, we can gain a richer and more nuanced appreciation for the remarkable journey of human development.

Chapter Review Practice Quiz

Chapter 2 Key Terms (see Glossary for definitions)

| accomodation |

information processing

|

| assimilation |

negative reinforcement

|

|

classical conditioning

|

positive reinforcement

|

|

conditioned stimulus

|

punisher |

|

continuous development

|

reciprocal determinism

|

|

developmental theories

|

reinforcer |

|

discontinuous development

|

social learning theory

|

|

ecological systems model

|

theory |

| epigenetics |

unconditioned stimulus

|

|

Erikson’s psychosocial theory

|

vicarious reinforcement

|

|

Freud’s theory of self (id, ego, superego)

|

zone of proximal development

|

|

guided participation

|

Media Attributions

- family-7257182_1280 © Alisa Dyson is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_02 © Robert Siegler. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Private: Chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_03 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Private: Chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_04 © Wikicommons is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_Include_V3_01 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_05 © Wikimedia

- chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_Include_V3_03 © Wikimedia is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Private: chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_Include_V3_04 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_Include_V3_05 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_06 © Wikimedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- chapter_2_Developmental_Theories_Include_V3_06 © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Ecological_systems_theory is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development

a plausible or scientifically acceptable general principle or body of principles offered to explain phenomena

developmental change occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and inset, universal sequence (development follows discontinuous development)

development occurs in separate stages

development is a slow and gradual process

development of id, ego, superego

8 stage theory describing key themes for human development centered around each age period

conditioning in which the conditioned stimulus (such as the sound of a bell) is paired with and precedes the unconditioned stimulus (such as the sight of food) until the conditioned stimulus alone is sufficient to elicit the response (such as salivation in a dog)

natural response to a stimulus

learned response to a stimulus

conditioning in which the desired behavior or increasingly closer approximations to it are followed by a rewarding or reinforcing stimulus

involves adding something to the situation in order to encourage a behavior

involves taking something away from the situation in order to encourage a behavior

used to encourage a behavior

anything that follows an act and decreases the chance it will reoccur

actions that are learned by watching others

the act of engaging in a behavior because we have seen it work for someone else

part of social learning theory' we are not just the product of our surroundings; rather we influence our surroundings. There is interplay between our personality and the way we interpret events and how they influence us

integrating knowledge into what is already known (no new changes)

knowledge that changes way of thinking, changing what is known, changing schema

otherwise known as scaffolding, when a teacher or capable peer helps a child learn cognitive skills within a certain range (zone of proximal development)

is the temporary support that parents or teachers give a child to do a task

the learner can do with guidance

based on the ideas and research of several cognitive scientists studying how individuals perceive, analyze, manipulate, use, and remember information

Brofenbrenner theory to explain layers/levels of interactions that impact development of individual

examines interplay in nature and nurture, examines how environmental factors can influence gene expression and, consequently, developmental outcomes