Chapter 5: Early Childhood

Objectives:

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- Summarize overall physical growth during early childhood. Identify examples of gross and fine motor skill development in early childhood.

- Describe growth of structures in the brain during early childhood.

- Identify nutritional concerns for children in early childhood.

- Describe sexual development in early childhood. Define preoperational intelligence.

- Identify animism, egocentrism, and centration.

- Describe changes to attention and memory in early childhood.

- Apply Vygotsky theory to early childhood. Illustrate scaffolding. Explain private speech. Explain theory of mind.

- Describe language development in early childhood.

- Explain Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development for toddlers and children in early childhood.

- Contrast models of parenting styles.

- Examine concerns about child care.

- Explain theory of self from Mead.

- Summarize theories of gender role development.

- Examine concerns about childhood stress and development.

The objectives are associated with the reading sections below.

Introduction

Our discussion will now focus on the physical, cognitive and socioemotional development during the ages from two to six, referred to as early childhood. Early childhood represents a time period of continued rapid growth, especially in the areas of language and cognitive development. Those in early childhood have more control over their emotions and begin to pursue a variety of activities that reflect their personal interests. Parents continue to be very important in the child’s development, but now teachers and peers exert an influence not seen with infants and toddlers.

Physical Development during Early Childhood

Growth in early childhood (Ob 1)

Children between the ages of 2 and 6 years tend to grow about 3 inches in height each year and gain about 4 to 5 pounds in weight each year. The 3-year-old is very similar to a toddler with a large head, large stomach, short arms, and legs. During early childhood, children start to lose some of their baby fat, making them less like a baby, and more like a child as they progress through this stage. By around age 3, children will have all 20 of their primary teeth, and by around age 4, may have 20/20 vision. But by the time the child reaches age 6, the torso has lengthened and body proportions have become more like those of adults. At six years of age, the average child in the United States is 45 inches tall (approximately 115 cm) and weighs 45 pounds (approximately 20.4 kg) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023).

Evidence indicates that the full height potential of our genetic inheritance is affected by several environmental influences. Economic disadvantage, physical neglect, disease, and malnutrition can affect biological and epigenetic mechanisms associated with height, which can take several generations to return to the normal range (Bogin, 2013; Lang et al., 2019; Simeone & Alberti, 2014). These influences may partly explain generational variations in height.

This growth rate is slower than that of infancy and is accompanied by a reduced appetite between the ages of 2 and 6. This change can sometimes be surprising to parents and lead to the development of poor eating habits. What children are eating is important to consider. Children who consume a lot of high-fat, sweet, and salty foods may fail to acquire a taste for other flavors. In contrast, adults who model positive eating habits, gently encourage children to try new foods, and avoid arguments over meals have a positive impact on children’s eating behavior. In short, children who are introduced to healthy vegetables and proteins on a regular basis will grow accustomed to them (Cardona Cano et al., 2015; Mahmood et al., 2021; Mazza et al., 2022; Nekitsing et al., 2018). Children between the ages of 2 and 3 need 1,000 to 1,400 calories, while children between the ages of 4 and 8 need 1,200 to 2,000 calories (Mayo Clinic, 2016a).

Nutritional concerns (Ob 3)

One directly observable consequence of malnutrition is stunting, or impaired growth in height. Stunting, which cannot be reversed and can increase cognitive and physical damage risks, has become a global concern (De Sanctis et al., 2021; Bhutta et al., 2020). Particularly in war-torn, severely impoverished, and drought-stricken areas, inadequate nutrition is widespread, and stunting is an inherent risk. As a result, an estimated 149 million children under five, or more than 20 percent of the global under-five population, undergo stunting. In some poor parts of Africa and southern Asia, the proportion rises to nearly half (UNICEF/World Health Organization [WHO]/World Bank Group, 2021).

Malnutrition is not common in developed nations like the United States, yet many children lack a balanced diet. Added sugars and solid fats contribute to 40% of daily calories for children and teens in the US. Approximately half of these empty calories come from six sources: soda, fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk (CDC, 2015). Caregivers need to keep in mind that they are setting up taste preferences at this age. Young children who grow accustomed to a high fat, very sweet, and salty flavors may have trouble eating foods that have subtler flavors such as fruits and vegetables.

By providing adequate, sound nutrition, and limiting sugary snacks and drinks, the caregiver can be assured that 1) the child will not starve, and 2) the child will receive adequate nutrition. Preschoolers can experience iron deficiencies if not given well-balanced nutrition and if given too much milk. Calcium interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well.

Consider the following advice about establishing eating patterns for years to come (Rice, 1997). Notice that keeping mealtime pleasant, providing sound nutrition, and not engaging in power struggles over food are the main goals:

Tips for Establishing Healthy Eating Patterns

| Don’t try to force your child to eat or fight over food. Of course, it is impossible to force someone to eat. But the real advice here is to avoid turning food into some kind of ammunition during a fight. Do not teach your child to eat to or refuse to eat in order to gain favor or express anger toward someone else. Recognize that appetite varies. Children may eat well at one meal and have no appetite at another. Rather than seeing this as a problem, it may help to realize that appetites do vary. Continue to provide good nutrition, but do not worry excessively if the child does not eat. Keep it pleasant. This tip is designed to help caregivers create a positive atmosphere during mealtime. Meal times should not be the time for arguments or expressing tensions. You do not want the child to have painful memories of mealtimes together or have nervous stomachs and problems eating and digesting food due to stress. No short order chefs. While it is fine to prepare foods that children enjoy, preparing a different meal for each child or family member sets up an unrealistic expectation from others. Children probably do best when they are hungry and a meal is ready. Limiting snacks rather than allowing children to “graze” continuously can help create an appetite for whatever is being served. Limit choices. If you give your preschool-aged child choices, make sure that you give them one or two specific choices rather than asking “What would you like for lunch?” If given an open choice, children may change their minds or choose whatever their sibling does not choose! Serve balanced meals. This tip encourages caregivers to serve balanced meals. A box of macaroni and cheese is not a balanced meal. Meals prepared at home tend to have better nutritional value than fast food or frozen dinners. Prepared foods tend to be higher in fat and sugar content as these ingredients enhance taste and profit margin because fresh food is often costlier and less profitable. However, preparing fresh food at home is not costly. It does, however, require more activity. Preparing meals and including the children in kitchen chores can provide a fun and memorable experience. Don’t bribe. Bribing a child to eat vegetable by promising desert is not a good idea. For one reason, the child will likely find a way to get the desert without eating the vegetables (by whining or fidgeting, perhaps, until the caregiver gives in), and for another reason, because it teaches the child that some foods are better than others. Children tend to naturally enjoy a variety of foods until they are taught that some are considered less desirable than others. A child, for example, may learn the broccoli they have enjoyed is seen as yucky by others unless it’s smothered in cheese sauce! |

To what extent do these tips address cultural practices? How might these tips vary by culture?

Brain Maturation (Ob 2)

Brain weight: If you recall, the brain is about 75 percent of its adult weight by two years of age. By age 6, it is at 95 percent its adult weight (yet only 30 percent of an adult body weight). Myelination and the development of dendrites continue to occur in the cortex and as it does, we see a corresponding change in what the child is capable of doing. The myelination of neurons that are essential to early physical development is mostly complete by 40 months of age. However, when life experiences are limited or the environment is highly stressful, myelination and overall brain growth will be slowed.

From an early age, the amount of stimulation a child receives has a significant effect on brain structure, weight, and volume (Gilmore et al, 2018; Lawson, 2013; Ziegler et al., 2020). Poor nutrition may also lead to deficits in myelin development and a general decrease in brain mass. However, the brain remains quite plastic in early childhood, and early intervention can often reverse these negative effects (de Faria et al., 2019). The brain continues to overproduce dendrites and synapses, which then leads to additional synaptic pruning. This alone tells us that brain plasticity remains strong, and that experiences and opportunities have roles in development. That the brain continually reorganizes itself tells us that a person’s environment has a persistent influence on outcomes.

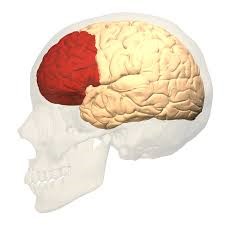

Greater development in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain behind the forehead that helps us to think, strategizes, and controls emotion, makes it increasingly possible to control emotional outbursts and to understand how to play games. The process of overproduction and pruning of synapses probably doesn’t stop until the third decade of life, especially in the prefrontal cortex (Kolk & Rakic, 2022).

Consider 4 or 5-year-old children and how they might approach a game of soccer. Chances are every move would be a response to the commands of a coach standing nearby calling out, “Run this way! Now, stop. Look at the ball. Kick the ball!” And when the child is not being told what to do, he or she is likely to be looking at the clover on the ground or a dog on the other side of the fence! Understanding the game, thinking ahead, and coordinating movement improves with practice and myelination. Not being too upset over a loss, hopefully, does as well.

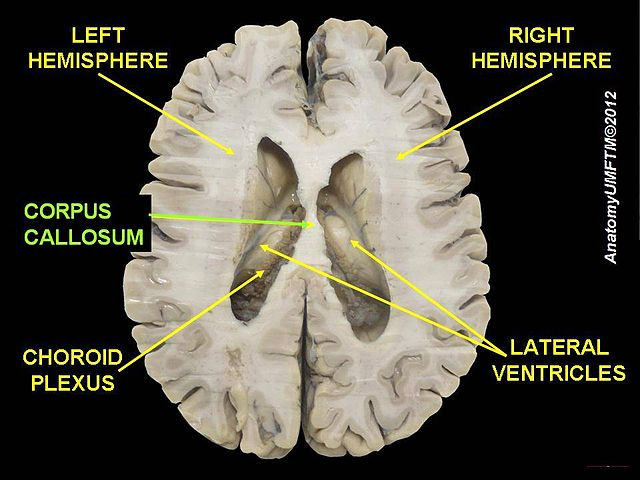

Growth in the Hemispheres and Corpus Callosum: The brain is lateralized. this organizational characteristic of the brain is known as lateralization. The left hemisphere typically handles language-related tasks such as reading, speaking, and thinking, while the right hemisphere specializes in emotional expression, musical ability, and recognition of visual-spatial relationships used in geometry, art, and navigation. Between ages 3 and 6, the left hemisphere of the brain grows dramatically. The right hemisphere continues to grow throughout early childhood and is involved in tasks that require spatial skills, such as recognizing shapes and patterns. The corpus callosum, a dense band of fibers that connects the two hemispheres of the brain, contains approximately 200 million nerve fibers that connect the hemispheres (Kolb & Whishaw, 2011).

The corpus callosum is located a couple of inches below the longitudinal fissure, which runs the length of the brain and separates the two cerebral hemispheres (Garrett, 2015). The hemispheres are independent, and they work together to process experiences and respond from the corpus callosum. Because the two hemispheres communicate with each other and integrate their activities through the corpus callosum. Additionally, because incoming information is directed toward one hemisphere, such as visual information from the left eye being directed to the right hemisphere, the corpus callosum shares this information with the other hemisphere. For example, reading a word relies on the right-hemisphere functions for visualization and then oral communication is a function of the left hemisphere. (There is no such thing as being “left-brained” or “right-brained.”)

The corpus callosum undergoes a growth spurt between ages 3 and 6, and this results in improved coordination between right and left hemisphere tasks. For example, in comparison to other individuals, children younger than 6 demonstrate difficulty coordinating an Etch A Sketch toy because their corpus callosum is not developed enough to integrate the movements of both hands (Kalat, 2016).

Neuroplasticity: The control of some specific bodily functions, such as movement, vision, and hearing, is performed in specified areas of the cortex, and if these areas are damaged, the individual will likely lose the ability to perform the corresponding function. For instance, if an infant suffers damage to facial recognition areas in the temporal lobe, it is likely that he or she will never be able to recognize faces (Farah et al., 2000). On the other hand, the brain is not divided up in an entirely rigid way. The brain’s neurons have a remarkable capacity to reorganize and extend themselves to carry out particular functions in response to the needs of the organism, and to repair the damage. As a result, the brain constantly creates new neural communication routes and rewires existing ones. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to change its structure and function in response to experience or damage. Neuroplasticity enables us to learn and remember new things and adjust to new experiences. Our brains are the most “plastic” when we are young children, as it is during this time that we learn the most about our environment. On the other hand, neuroplasticity continues to be observed even in adults (Kolb & Fantie, 1989).

Right or left-handed?

Handedness is an example of lateralization in action. About 10 percent of children across cultures and continents prefer to use their left hand, a preference linked to differences in brain organization and genes. Whereas about 95 percent of right-handed people show typical lateralization patterns (like language centers in the left hemisphere), only about 75 percent of left-handers do (de Kovel et al., 2019). Though some studies indicate that most children develop an obvious hand preference by six months of age, others find that stable preferences may not appear until age nine or even later (Scharoun & Bryden, 2014). However, by that time, most children have already been required to favor one hand over another in school tasks like coloring, writing, and using a mouse.

Differences in cognition, artistic expression, and athletic prowess between left-handed and right-handed children are often reported. However, no scientific evidence suggests that these differences exist (McManus, 2019). Nonetheless, children who are left-hand dominant often struggle with products designed for right-handers, such as scissors, seat belts, and school desks. Though we can learn to use our non-dominant hand quite well, hand dominance appears to be highly heritable and unchangeable. Even identical twins, who share the same genes, may favor different hands; each has the same 10 percent chance of being left-handed. This indicates that handedness results from a combination of environmental and genetic influences (Schmitz et al., 2017).

Motor Skill Development (Ob 1)

Early childhood is a time when children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging, and clapping and every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant affords the opportunity to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of early childhood. Children continue to improve their gross motor skills as they run and jump, and frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me” while they hop or roll down a hill. Gross motor skills involve larger muscle groups in legs and arms or entire body. Children’s songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right. Fine motor skills involve smaller action muscle coordination, and are also being refined in activities such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and using scissors. Some children’s songs promote fine motor skills (have you ever heard of the song “itsy, bitsy, spider”?).

The development of greater coordination of muscles groups and finer precision can be seen during this time period. Thus, average 2-year-olds may be able to run with slightly better coordination than they managed as a toddler, yet they would have difficulty pedaling a tricycle, something the typical 3-year-old can do. We see similar changes in fine motor skills with 4-year-olds who no longer struggle to put on their clothes, something they may have had problems with two years earlier. Mastering the fine art of cutting one’s own fingernails or tying shoes will take a lot of practice and maturation. Motor skills continue to develop into middle childhood, but for those in early childhood, play that deliberately involves these skills is emphasized.

By the time children arrive at middle childhood, they will have developed the general capabilities to perform movements like those of adults—though with far less skill and strength. However, due to their relatively immature cognitive abilities and still-developing brains, children don’t yet fully grasp certain aspects of motion, such as the trajectory of a rolling ball in a game of soccer or kickball. For these reasons, younger children are usually offered accommodations when engaging in physical activities. For instance, their slower reaction time and lack of skill necessitates the use of equipment like training wheels on a bicycle or a batting tee in T-ball.

Table: Examples of Motor skill Milestones for children 2 to 5 years old

| Gross Motor Skills | Fine Motor Skills | |

| Age 2 |

Can kick a ball without losing balance Can pick up objects while standing, without losing balance (This often occurs by 15 months. It is a cause for concern if not seen by 2 years.) Can run with better coordination. (May still have a wide stance.) |

Able to turn a doorknob Can look through a book turning one page at a time Can build a tower of six to seven cubes Able to put on simple clothes without help (The child is often better at removing clothes than putting them on) |

| Age 3 |

Can briefly balance and hop on one foot May walk on stairs with alternating feet (without holding onto rail) Can pedal a tricycle |

Can build a block tower of more than nine cubes Can easily place small objects in a small opening Can copy a circle Drawing a person with 3 parts Feeds self easily |

| Age 4 |

Shows improved balance Hops on one foot without losing balance Throws a ball overhead with coordination |

Can cut out a picture using scissors Drawing a square Managing a spoon and fork neatly while eating Putting on clothes properly |

| Age 5 |

Has better coordination (getting the arms, legs, and body to work together) Skips, jumps and hops with good balance Stays balanced while standing on one foot with eyes closed |

Shows more skills with simple tools and writing utensils Can copy a triangle Can use a knife to spread soft foods |

Table adapted from (NIH, 2018)

Children’s art: Have you ever examined the drawings of young children? If you look closely, you can almost see the development of motor skills, perceptual understanding, and cognition reflected in the way these images change as pathways become more mature. Early scribbles and dots illustrate the use of simple motor skills. No real connection is made between an image being visualized and what is created on paper.

Rhoda Kellogg (1969) noted that children’s drawings underwent several transformations. Starting with about 20 different types of scribbles at age 2, children move on to experimenting with the placement of scribbles on the page. By age 3 they are using the basic structure of scribbles to create shapes and are beginning to combine these shapes to create more complex images. By 4 or 5 children are creating images that are more recognizable representations of the world. These changes are a function of improvement in motor skills, perceptual development, and cognitive understanding of the world (Cote & Golbeck, 2007).

The drawing of tadpoles is a pervasive feature of young children’s drawings of self and others. Tadpoles emerge in children’s drawing at about the age of 3 and have been observed in the drawings of young children around the world (Gernhardt et al., 2015). Despite the universality of tadpoles in children’s drawings, there are cultural variations in the size, number of facial features, and emotional expressions displayed. Gernhardt et al. (2015) found that children from Western contexts (i.e., urban areas of Germany and Sweden) and urban educated non-Western contexts (i.e., urban areas of Turkey, Costa Rica, and Estonia) drew larger images, with more facial detail and more positive emotional expressions, while those from non-Western rural contexts (i.e., rural areas of Cameroon and India) depicted themselves as smaller, with less facial details and a more neutral emotional expression. The authors suggest that cultural norms of non-Western traditionally rural cultures, which emphasize the social group rather than the individual, may be one of the factors for the difference in the size of the figure. The tadpole figures of children from Western cultures often took up most of the page. Coming from cultures that emphasize the individual, this should not be surprising.

Physical Activity is Important!

We know that during early childhood, parents and caregivers should encourage activities and play that emphasize motor skills and combat sedentary behavior and habits. After all, the brain literally grows when children engage in new opportunities. Additionally, it’s well-established that early physical activity has a positive impact on later health outcomes (Pate et al., 2019; Roychowdhury, 2020; Wyszyńska et al., 2020), including weight and cardiovascular fitness. It is also linked to lower risks of chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and certain cancers. Moreover, children who engage in physical activity during early childhood have higher bone density, which may help prevent osteoporosis in later life (Pate et al., 2019).

Active children also have stronger cognitive development, including improved attention, self-regulation, and academic performance (Mualem et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2020). Substantial evidence shows that throughout the lifespan, regular physical activity leads to better overall cognitive development (Erickson et al., 2019). Even a single 30-minute session has been shown to be beneficial in improving motor activity and memory for preschool children (McDonnell et al., 2013).

Here are the recommendations from WHO (2024):

- three- and four-year-old children should spend a minimum of three hours per day engaged in a variety of physical activities, including at least sixty minutes of moderate intensity to promote overall healthy development (WHO, 2022). Moderately intense activities include walking a dog, dancing, and riding a tricycle.

- five to six years old, the WHO recommends that children participate in a minimum of sixty minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per day. This can include normal school recess activities like climbing and playing games with balls. At least three times per week, children this age should engage in more vigorous aerobic activity, like games of tag, soccer, or basketball. High-intensity physical activities are especially important for building bone strength and muscle development (Gunter et al., 2012; Specker et al., 2015).

Get kids to get moving!

Toilet Training

Toilet training typically occurs during the first two years of early childhood (24-36 months). Some children show interest by age 2, but others may not be ready until months later. The average age for girls to be toilet trained is 29 months and for boys, it is 31 months (Boyse & Fitzgerald, 2010). One study indicated that only 40 to 60 percent of children complete toilet training by 36 months of age (Blum et al., 2004). Most children have control over both bladder and bowels and leave diapers behind sometime between 3 and 4 years old. The child’s age is not as important as his/her physical and emotional readiness. If started too early, it might take longer to train a child.

According to the Mayo Clinic (2016b), the following questions can help parents determine if a child is ready for toilet training:

- Does your child seem interested in the potty chair or toilet, or in wearing underwear?

- Can your child understand and follow basic directions?

- Does your child tell you through words, facial expressions or posture when he or she needs to go?

- Does your child stay dry for periods of two hours or longer during the day?

- Does your child complain about wet or dirty diapers?

- Can your child pull down his or her pants and pull them up again?

- Can your child sit on and rise from a potty chair? (p. 1)

If a child resists being trained or it is not successful after a few weeks, it is best to take a break and try again later. Most children master daytime bladder control first, typically within two to three months of consistent toilet training. However, nap and nighttime training might take months or even years.

Some children experience elimination disorders that may require intervention by the child’s pediatrician or a trained mental health practitioner. Elimination disorders include enuresis, or the repeated voiding of urine into bed or clothes (involuntary or intentional) and encopresis, the repeated passage of feces into inappropriate places (involuntary or intentional) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The prevalence of enuresis is 5%-10% for 5-year-olds, 3%-5% for 10-year-olds and approximately 1% for those 15 years of age or older. Around 1% of 5-year-olds have encopresis, and it is more common in males than females.

Sleep

Sleep is important for mood regulation and attention (NSF, 2015). In cases where children are tired they actually do not look tired. Children needing more sleep may resist bedtime and become hyper as the evening goes on. During early childhood, there is wide variation in the number of hours of sleep recommended per day. For example, 2-year-olds may still need 14 hours per day, while a six-year-old may only need 9 hours. According to the WHO, preschool children typically need ten to thirteen hours of sleep every twenty-four hours and to maintain consistent sleep and wake times. Children who have stopped napping sleep more at night, getting the same amount of sleep overall as their peers who nap (Ward et al., 2008; WHO, 2019).

The National Sleep Foundation’s 2015 recommendations based on age are listed in the next table.

Table. Age groups and sleep duration recommendations

| Age Range | Typically needed each day | May be appropriate |

| Infant (4-11 months) | 12-15 hours | Not less than 10 and not more than 18 hours |

| Toddler (1-2 years) | 11-14 hours | Not less than 9 and not more than 16 hours |

| Preschooler (3-5 years) | 10-13 hours | Not less than 8 and not more than 14 hours |

| School age (6-13 years) | 9-11 hours | Not less than 7 and not more than 12 hours |

| Teenager (14-17 years) | 8-10 hours | Not less than 7 and not more than 11 hours |

Table adapted from Hirskowitz (2015)

Sexual Development in Early Childhood (Ob 4)

Sexual and gender development are two different processes, but a misconception is that they are connected. We will first focus on children’s sexual development, and later in the chapter discuss gender development. Historically, children have been thought of as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal (Aries, 1962). Yet, the physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth. However, it is not appropriate to associate the elements of seduction, power, love, or lust that is part of the adult meanings of sexuality. Sexuality begins in childhood as a response to physical states and sensation and cannot be interpreted as similar to that of adults in any way (Carroll, 2007).

Boys and girls are capable of erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth (Martinson, 1981). Arousal can signal overall physical contentment and stimulation that accompanies feeding or warmth. And infants begin to explore their bodies and touch their genitals as soon as they have sufficient motor skills. This stimulation is for comfort or to relieve tension rather than to reach orgasm (Carroll, 2007).

Early Childhood: Children 4 years old and younger are naturally immodest, and may display open—and occasionally startling–curiosity about other people’s bodies and bodily functions, such as touching women’s breasts, or wanting to watch when grownups go to the bathroom (NCTSN, 2009). Wanting to be naked (even if others are not) and showing or touching private parts while in public are also common in young children (NCTSN, 2009). They are curious about their own bodies and may quickly discover that touching certain body parts feels nice (NCTSN, 2009). Self-stimulation is common in early childhood for both boys and girls. Curiosity about the body and about others’ bodies is a natural part of early childhood as well.

As children age and interact more with other children (approximately ages 4–6), they become more aware of the differences between boys and girls, and more social in their exploration (NCTSN, 2009). As children grow, they are more likely to show their genitals to siblings or peers, and to take off their clothes and touch each other (Okami et al., 1997). In addition to exploring their own bodies through touching or rubbing their private parts (masturbation), they may begin “playing doctor” and copying adult behaviors such as kissing and holding hands (NCTSN, 2009). Boys are often shown by other boys how to masturbate. Boys masturbate more often and touch themselves more openly than do girls (Schwartz, 1999). As children become increasingly aware of the social rules governing sexual behavior and language (such as the importance of modesty or which words are considered “naughty”), they may try to test these rules by using naughty words (NCTSN, 2009). They may also ask more questions about sexual matters, such as where babies come from, and why boys and girls are physically different (NCTSN, 2009). Messages about what is going on and the appropriate time and place for such activities help the child learn what is appropriate.

What is typical for young children’s sexuality? (NCTSN, 2009)

| Preschool children (less than 4 years) ■ Explore and touch private parts, in public and in private ■ Rub private parts (with hand or against objects) ■ Show private parts to others ■ Try to touch mother’s or other women’s breasts ■ Remove clothes and wanting to be naked ■ Attempt to see other people when they are naked or undressing (such as in the bathroom) ■ Ask questions about their own—and others’—bodies and bodily functions ■ Talking to children their own age about bodily functions such as “poop” and “pee” |

| Young Children (approximately 4-6 years) ■ Purposefully touch private parts (masturbation), occasionally in the presence of others ■ Attempt to see other people when they are naked or undressing ■ Mimic dating behavior (such as kissing, or holding hands) ■ Talk about private parts and using “naughty” words, even when they don’t understand the meaning ■ Explore private parts with children |

Parents play a pivotal role in helping their children develop healthy attitudes and behaviors towards sexuality (NCTSN, 2009). Although talking with your children about sex may feel outside your comfort zone, there are many resources available to help you begin and continue the conversation about sexuality. It is important to remain calm and event tone and ask open-ended questions when you feel unsettled over something your child said or you have seen him/her do. A behavior that is not typical should not be ignored and it may mean that your child needs to learn something from the situation (e.g., private parts are private). Providing close supervision, and providing clear, positive messages about modesty, boundaries, and privacy are crucial as children move through the periods of childhood (NCTSN, 2009). By talking openly with your children about relationships, intimacy, and sexuality, you can foster their healthy growth and development (NCTSN, 2009).

Basic Information Parents can share with Early Childhood (Before 4 years old) (NCTSN, 2009)

| ■ Boys and girls are different ■ Accurate names for body parts of boys and girls ■ Babies come from mommies ■ Rules about personal boundaries (for example, keeping private parts covered, not touching other children’s private parts) ■ Give simple answers to all questions about the body and bodily functions. |

Photo courtesy of Flickr |

Safety Information for Early Childhood (NCTSN, 2009)

■ The difference between “okay” touches (which are comforting, pleasant, and welcome) and “not okay” touches (which are intrusive, uncomfortable, unwanted, or painful)

■ Your body belongs to you

■ Everyone has the right to say “no” to being touched, even by grown-ups

■ No one—child or adult–has the right to touch your private parts

■ It’s okay to say “no” when grownups ask you to do things that are wrong, such as touching private parts or keeping secrets from mommy or daddy

■ There is a difference between a “surprise”–which is something that will be revealed sometime soon, like a present—and a “secret,” which is something you’re never supposed to tell. Stress that it is never okay to keep secrets from mommy and daddy

■ Who to tell if people do “not okay” things to you, or ask you to do “not okay” things to them

Basic Information to share with Young Children (approximately 4-6 years) (NCTSN, 2009)

| ■ Boys’ and girls’ bodies change when they get older. ■ Simple explanations of how babies grow in their mothers’ wombs and about the birth process. ■ Rules about personal boundaries (such as, keeping private parts covered, not touching other children’s private parts) ■ Simple answers to all questions about the body and bodily functions ■ Touching your own private parts can feel nice, but is something done in private |

Photo courtesy of Flickr |

Safety Information for Young Children (NCTSN, 2009)

■ Sexual abuse is when someone touches your private parts or asks you to touch their private parts

■ It is sexual abuse even if it is by someone you know

■ Sexual abuse is NEVER the child’s fault

■ If a stranger tries to get you to go with him or her, run and tell a parent, teacher, neighbor, police officer, or other trusted adult

■ Who to tell if people do “not okay” things to you, or ask you to do “not okay” things to them (NCTSN, 2009)

Cognitive Development

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning some basic principles about how the world works, they hold some pretty interesting initial ideas. For example, how many of you are afraid that you are going to go down the bathtub drain? Hopefully, none of you do! But a 3-year-old might really worry about this as they sit at the front of the bathtub. A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Or the young child may ask, “How long are we staying? From here to here?” while pointing to two points on a table. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size, and distance are not easy to grasp at this young age. Understanding size, time, distance, fact, and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years.

Preoperational Intelligence (Ob 5)

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development has a stage that coincides with early childhood known as the Preoperational Stage. According to Piaget, this stage occurs from the age of 2 to around 7 years. In the preoperational stage, children use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as she zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information. The term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered pre-operational. Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge.

Let’s examine some Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities during the Preoperational Stage.

Pretend Play: Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land!

Piaget believed that children’s pretend play helped children solidify new schemes they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflected changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have taught (Berk, 2007).

Egocentrism: Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children to think that everyone sees things in the same way as the child. For example, 10-year-old Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so her mom takes 3-year-old Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too. Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a 3-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see. Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own, rather than the doll’s view. By age 7 children are less self-centered. Additionally, when children are speaking to others, they tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Animism: Animism refers to attributing lifelike qualities to objects. An example could be a child believing that the sidewalk was mad and made them fall down, or that the stars twinkle in the sky because they are happy. To the imaginative child, the cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive but after age 3, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Classification Errors: Preoperational children have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. Classification is the ability to simultaneously sort things into general and more specific groups, using different types of comparisons. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or white buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. The child does not identify the category of buttons being larger than each subgroup (black and white) indicating a lack of hierarchy classification. Most children develop hierarchical classification ability between the ages of 7 and 10. As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed, the ability to classify objects improves.

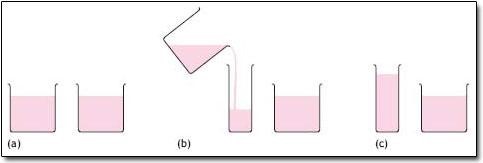

Conservation Errors: Children in the preoperational stage do not understand conversation. Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity. Imagine a 2-year-old and 4-year-old eating lunch. The 4-year-old has a whole peanut butter and jelly sandwich. He notices, however, that his younger sister’s sandwich is cut in half and protests, “She has more!” This is a conservation error of number. He does not realize that 2 half sandwiches make a whole sandwich. Often children who fail conservation errors will concentrate on one aspect (focusing on number of sandwiches verses the total size (or mass)). Centration is the act of focusing all attention on one characteristic or dimension of a situation while disregarding all others. He is exhibiting centration by focusing on the number of pieces, which results in a conservation error.

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005). The child usually notes that the beakers do contain the same amount of liquid. When one of the beakers is poured into a taller and thinner container, children who are younger than seven or eight years old typically say that the two beakers no longer contain the same amount of liquid, and that the taller container holds the larger quantity (centration), without taking into consideration the fact that both beakers were previously noted to contain the same amount of liquid.

Irreversibility is also demonstrated during this stage and is closely related to the ideas of centration and conservation. Irreversibility refers to the young child’s difficulty mentally reversing a sequence of events. In the same beaker situation, the child does not realize that, if the sequence of events was reversed and the water from the tall beaker was poured back into its original beaker, then the same amount of water would exist.

| Conservation Errors Revisited.

Let’s look at Kenny and Keiko again. Dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to 3-year-old Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Kenny did not understand that cutting the pizza into smaller pieces did not increase the overall amount. Kenny focused on the five pieces of pizza to his sister’s one piece even though the total amount was the same. What error was Kenny making? |

Centration, conservation errors, and irreversibility are indications that young children are reliant on visual representations. Because children have not developed this understanding of conservation, they cannot perform mental operations (a requirement for Piaget’s next stage).

Critique of Piaget: Similar to the critique of the sensorimotor period, several psychologists have attempted to show that Piaget also underestimated the intellectual capabilities of young children. For example, children’s specific experiences can influence when they are able to conserve. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams et al., 1969). Crain (2005) indicated that preoperational children could think rationally on mathematical and scientific tasks, and they are not as egocentric as Piaget implied. Research on Theory of Mind (discussed later in the chapter) has demonstrated that children overcome egocentrism by 4 or 5 years of age, which is sooner than Piaget indicated.

Children & Learning – The Mozart Effect: Is there a cognitive advantage for children to listen to classical music?

I’m sure everyone has heard at some point in their life that listening to classical music supposedly makes one smarter. There are many different meanings you could interpret from that statement. Does classical music have a permanent effect in raising one’s IQ just by listening? Does it only improve intelligence for a short time after listening? What areas of intelligence is the music supposed to improve? These are all questions you should be asking when you hear a statement such as “listening to classical music makes kids smarter”. This topic became the infamous anomaly it is today from a Russian study in 1993. In this study 36 college students were split into 3 separate groups where each group would sit in a room either listening to Mozart, concentration therapy sounds, or complete silence for 10 minutes. After the 10 minutes was up they all would take a short intelligence quiz with special reasoning tasks. What this study found is that the Mozart listening group scored slightly higher on the test than the other 2 groups.

According to further research, including a meta-analysis (Chabis, 1999), what was found out is the music does not in fact have any benefit in raising one’s intelligence. The classical music puts the listener’s brain in a state of higher awareness than normal so when given a reasoning intelligence task, the listener is more aware and should perform slightly better. Listening to classical music while performing a task such as reading can in fact impair one’s ability to comprehend all the information read because the music distracts the mind when you may not even realize it (Yen-Ning Su, 2017). Another study done showed that learning how to play music very well can improve a person’s spatial intelligence (Bower, 2004). Overall, the relationship music can have on one’s intelligence is clear that it does not in any way raise it, rather it evokes the mind to be on its feet ready for a task.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development (Ob 7)

In contrast to Piaget on the child as the active learner, Lev Vygotsky argued that a child’s intrinsic development and the highest level of cognitive thinking is elicited from the language, writings, and concepts arising from the culture the child is surrounded by (Crain, 2005). He believed that social interactions with adults and more learned peers could facilitate a child’s potential for learning. Without this interpersonal instruction, he believed children’s minds would not advance very far as their knowledge would be based only on their own discoveries. Vygtosky’s theory including cultural and societal factors in learning go beyond supervision and peer relationships. They extend to the availability of resources such as books, tutors, mentors, and extra learning opportunities. Think about the ways that children learn to process information differently in varied sociocultural situations.

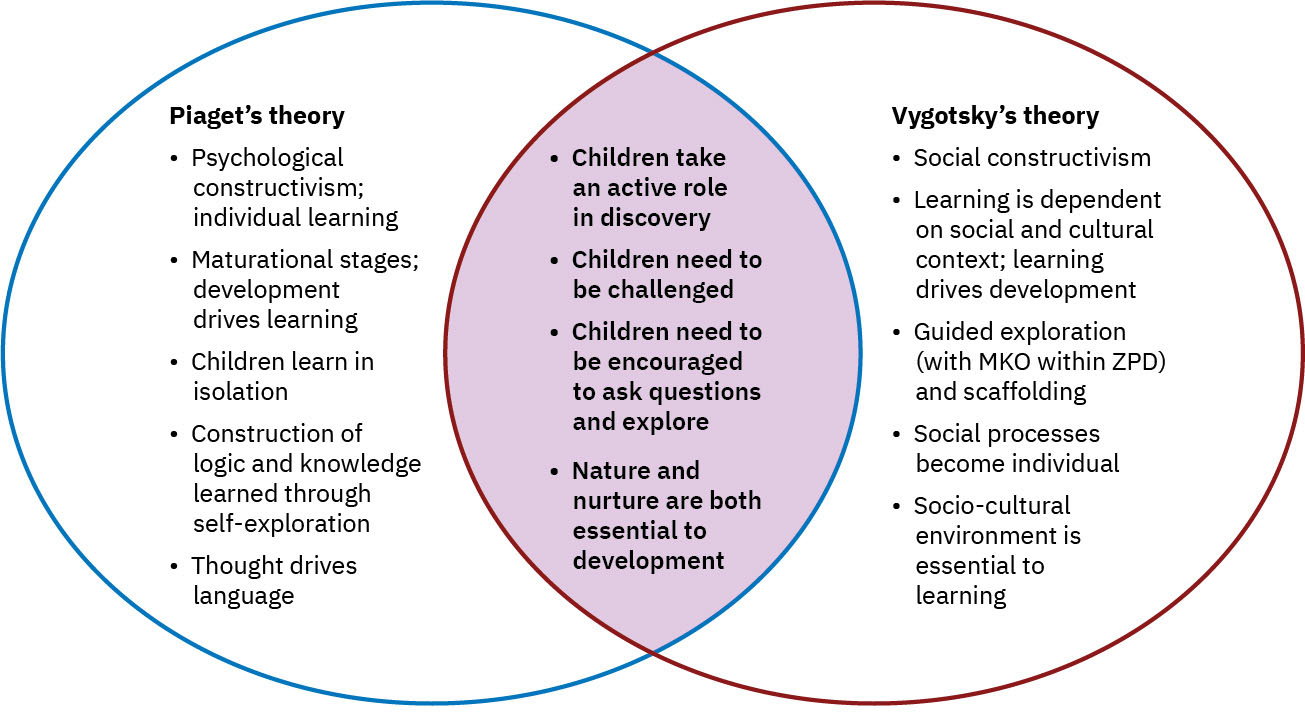

Below shows a comparison between Vygotsky’s theory and Piaget’s theory, although they identify learning takes different approaches, there are some shared concepts about learning.

Let’s review some of Vygotsky’s key concepts (as mentioned in chapter 2).

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding: Vygotsky’s best-known concept is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Vygotsky stated that children should be taught in the ZPD, which occurs when they can almost perform a task, but not quite on their own without assistance. With the right kind of teaching, however, they can accomplish it successfully. A good teacher identifies a child’s ZPD and helps the child stretch beyond it. Then the adult (teacher) gradually withdraws support until the child can then perform the task unaided. Researchers have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to this way of teaching. Scaffolding is the temporary support that parents or teachers give a child to do a task, sometimes the term guided participation is also used.

Private Speech: Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech (or private speech), and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962). Piaget interpreted this as Egocentric Speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from another’s point of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in Private Speech or inner speech.

Theory of Mind (Ob 7)

Imagine showing a 3-year old child a Band-Aid box and asking the child what is in the box. Chances are, the child will reply, “Band-Aids.” Now imagine that you open the box and pour out crayons. If you ask the child what they thought was in the box before it was opened, they may respond, “crayons.” If you ask what a friend would have thought was in the box, the response would still be “crayons.” Why? Before about 4 years of age, a child does not recognize that the mind can hold ideas that are not accurate. So, this 3-year-old changes his or her response once shown that the box contains crayons. The theory of mind is the understanding that the mind can be tricked or that the mind is not always accurate. At around age 4, the child would reply, “Crayons” and understand that thoughts and realities do not always match.

Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). For the theory of mind, a child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true. In Piagetian terms, they must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they “believe” rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age 4 children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman et al., 2001).

This awareness of the existence of mind is part of social intelligence or the ability to recognize that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways and it helps us to be able to be understanding or empathetic toward others. This mind reading ability helps us to anticipate and predict the actions of others (even though these predictions are sometimes inaccurate). This is important for communication and social skills.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

The characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are seen during early childhood (as established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). So, what exactly is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Children with this disorder show signs of “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction” and “restricted, repetitive patterns” of behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Children with ASD experience difficulties with explaining and predicting other people’s behavior, which leads to problems in social communication and interaction. Children who are diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder usually develop the theory of mind more slowly than other children and continue to have difficulties with it throughout their lives.

ASD occurs in around 17 percent of children and can manifest with a wide range of highly diverse symptoms and neurological characteristics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). The average age to receive a diagnosis is 4.5 years old, though many individuals are diagnosed at later ages, including in adulthood (Brett et al., 2016).

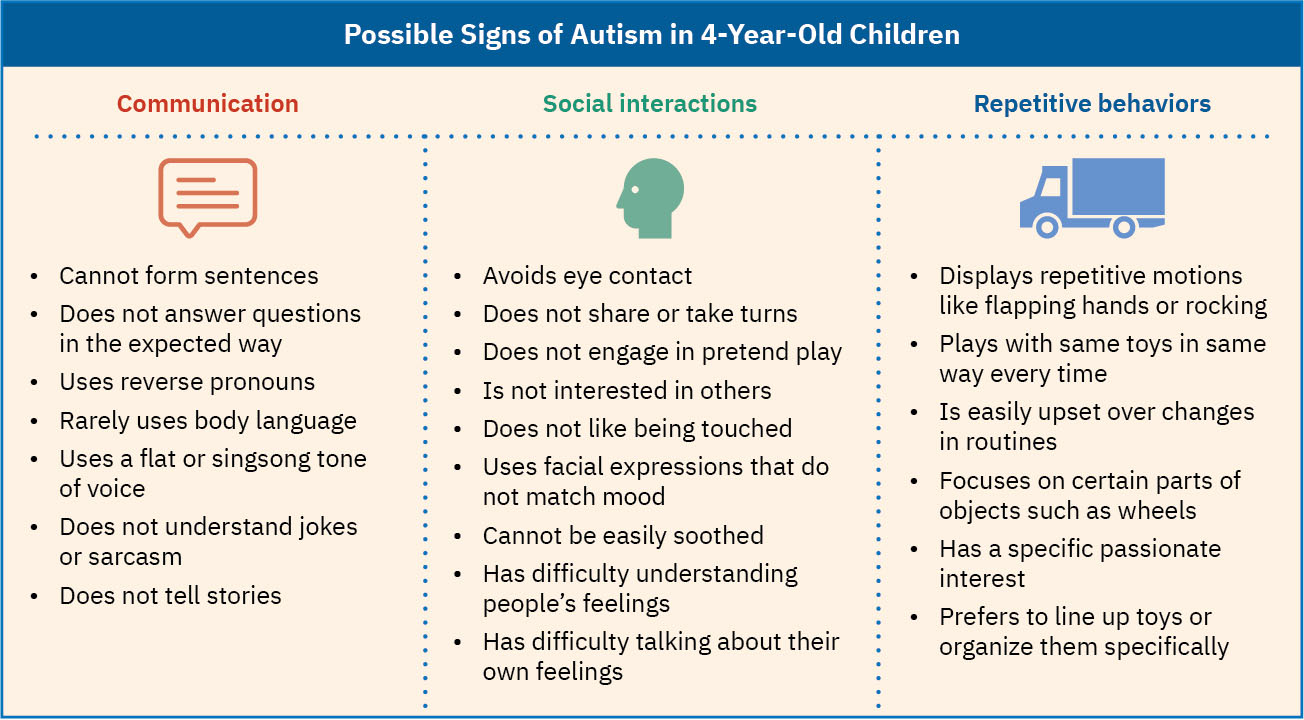

There are many possible signs of autism spectrum disorder, and the appearance of some does not imply ASD is present. However, early signs may warrant a referral to a specialist for professional assessment. The table shows possible signs for a four-year-old.

Some of the common traits that appear in early childhood are struggles with social interactions, particularly making eye contact, responding reciprocally, understanding the perspectives of others, and communicating verbally. These noticeable differences in social interactions among autistic preschoolers often result in parental concerns and referrals to specialists (see table above). Note that most psychologists use the phrase autistic preschooler (identity-first language) as opposed to person with autism spectrum disorder (person-first language) because a large percentage of allies and advocates in the autistic community have stated this language preference. The language and preferences for any neurodiversity or disorder vary by the individual and the represented community. When in doubt, always follow the lead of the person or ask their preference (Autistic Self Advocacy Network, n.d.; Ladau, 2021).

Beyond early childhood, those with autism spectrum disorders may follow unique developmental trajectories. TThe qualifier “spectrum” in autism spectrum disorder is used to indicate that individuals with the disorder can show a range, or spectrum, of symptoms that vary in their magnitude and severity: Some severe, others less severe. Though ASD is lifelong, some children develop skills like those of their non-autistic peers, whereas others may continue to struggle with particular social and emotional expectations across the lifespan (Elder et al., 2017). Some individuals with an autism spectrum disorder, particularly those with better language and intellectual skills, can live and work independently as adults.

Early diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child’s unusual behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months, but often a diagnosis comes later, and individual cases vary significantly. Typical early signs of autism include:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

Information Processing in Early Childhood (Ob 6)

The information processing model examines how memory gets stored (mentioned in chapter 2). Information processing researchers focus on several issues in cognitive development for this age group, including improvements in attention skills, changes in the capacity and the emergence of executive functions in working memory. Additionally, in early childhood memory strategies, memory accuracy, and autobiographical memory emerge. Early childhood is seen by many researchers as a crucial time period in memory development (Posner & Rothbart, 2007).

Attention

Changes in attention have been described by many as the key to changes in human memory (Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). However, attention is not a unified function; it is comprised of sub-processes. The ability to switch our focus between tasks or external stimuli is called divided attention or multitasking. This is separate from our ability to focus on a single task or stimulus while ignoring distracting information, called selective attention. Different from these is sustained attention, or the ability to stay on task for long periods of time. Moreover, we also have attention processes that influence our behavior and enable us to inhibit a habitual or dominant response and others that enable us to distract ourselves when upset or frustrated.

Divided Attention: Young children (age 3-4) have considerable difficulties in dividing their attention between two tasks, and often perform at levels equivalent to our closest relative, the chimpanzee, but by age 5 they have surpassed the chimp (Hermann et al., 2015; Hermann & Tomasello, 2015). Despite these improvements, 5-year-olds continue to perform below the level of school-age children, adolescents, and adults.

Selective Attention: Children’s ability with selective attention tasks improve as they age. However, this ability is also greatly influenced by the child’s temperament (Rothbart & Rueda, 2005), the complexity of the stimulus or task (Porporino et al., 2004), and along with whether the stimuli are visual or auditory (Guy et al., 2013). Guy et al. (2013) found that children’s ability to selectively attend to visual information outpaced that of auditory stimuli. This may explain why young children are not able to hear the voice of the teacher over the cacophony of sounds in the typical preschool classroom (Jones et al., 2015). Jones and his colleagues found that 4 to 7-year-olds could not filter out background noise, especially when its frequencies were close in sound to the target sound. In comparison, 8 to 11-year-old older children often performed similarly to adults.

Sustained Attention: Most measures of sustained attention typically ask children to spend several minutes focusing on one task, while waiting for an infrequent event, while there are multiple distractors for several minutes. Berwid et al. (2005) asked children between the ages of 3 and 7 to push a button whenever a “target” image was displayed, but they had to refrain from pushing the button when a non-target image was shown. The younger the child, the more difficulty he or she had maintaining their attention.

Memory

Based on studies of adults, people with amnesia, and neurological research on memory, researchers have proposed several “types” of memory.” Let’s examine changes in memory during early childhood.

Sensory memory (also called the sensory register): the first stage of the memory system, and it stores sensory input in its raw form for a very brief duration; essentially long enough for the brain to register and start processing the information. Studies of auditory sensory memory have found that the sensory memory trace for the characteristics of a tone lasts about one second in 2-year-olds, two seconds in 3-year-olds, more than two seconds in 4-year-olds and three to five seconds in 6-year-olds (Glass et al., 2008). Other researchers have found that young children hold sounds for a shorter duration than do older children and adults and that this deficit is not due to attentional differences between these age groups, but reflect differences in the performance of the sensory memory system (Gomes et al., 1999).

Short-term or working memory: The second stage of the memory system. Working memory is the component of memory in which current conscious mental activity occurs. Working memory often requires conscious effort and adequate use of attention to function effectively. As you read earlier, children in this age group struggle with many aspects of attention and this greatly diminishes their ability to consciously juggle several pieces of information in memory. The capacity of working memory, that is the amount of information someone can hold in consciousness, is smaller in young children than in older children and adults. The typical adult and teenager can hold a 7-digit number active in their short-term memory. The typical 5-year-old can hold only a 4-digit number active. This means that the more complex a mental task is, the less efficient a younger child will be in paying attention to, and actively processing, the information in order to complete the task.

Long-term memory also is known as permanent memory: the third component in memory. A basic division of long-term memory is between declarative and nondeclarative memory. Declarative memories, sometimes referred to as explicit memories, are memories for facts or events that we can consciously recollect. Nondeclarative memories sometimes referred to as implicit memories, are typically automated skills that do not require conscious recollection. Remembering that you have an exam next week would be an example of declarative memory. In contrast, knowing how to walk so you can get to the classroom or how to hold a pencil to write would be examples of non-declarative memories. Declarative memory is further divided into semantic and episodic memory. Semantic memories are memories for facts and knowledge that are not tied to a timeline, while episodic memories are tied to specific events in time.

A component of episodic memory is autobiographical memory or our personal narrative. Autobiographical memories are a subset of the declarative memory category. As you may recall from Chapter 4, the concept of infantile amnesia was introduced. Adults rarely remember events from the first few years of life. In other words, we lack autobiographical memories from our experiences as an infant, toddler, and very young preschooler. Several factors contribute to the emergence of autobiographical memory including brain maturation, improvements in language, opportunities to talk about experiences with parents and others, the development of the theory of mind, and a representation of “self” (Nelson & Fivush, 2004). 2-year-olds do remember fragments of personal experiences, but these are rarely coherent accounts of past events (Nelson & Ross, 1980). Between 2 and 2 ½ years of age, children can provide more information about past experiences. However, these recollections require considerable prodding by adults (Nelson & Fivush, 2004). Over the next few years, children will form more detailed autobiographical memories and engage in more reflection of the past.

Executive function (EF)

Self-regulatory processes, such as the ability to inhibit behavior or cognitive flexibility, that enable adaptive responses to new situations or to reach a specific goal, are aspects of executive function. Executive function skills gradually emerge during early childhood and continue to develop throughout childhood and adolescence. Like many cognitive changes, brain maturation, especially the prefrontal cortex, along with experience influence the development of executive function skills. A child, whose parents are warm and responsive, use scaffolding when the child is trying to solve a problem, and who provide cognitively stimulating environments for the child show higher executive function skills (Fay-Stammbach et al., 2014). For instance, scaffolding was positively correlated with greater cognitive flexibility at age 2 and inhibitory control at age 4 (Bibok et al., 2009).

Executive function also is related to the use and selection of mental strategies to aid their memory performance. For instance, simple rote rehearsal may be used to commit information to memory. Young children, however, often do not rehearse unless reminded to do so, and when they do rehearse, they often fail to use clustering rehearsal. In clustering rehearsal, the person rehearses previous material while adding in additional information. If a list of words is read out loud to you, you are likely to rehearse each word as you hear it along with any previous words you were given. Young children will repeat each word they hear, but often fail to repeat the prior words in the list. In Schneider et al. (2009) longitudinal study of 102 kindergarten children, the majority of children used no strategy to remember information, a finding that was consistent with previous research. As a result, their memory performance was poor when compared to their abilities as they aged and started to use more effective memory strategies.

Summary of three cognitive theories

We have discussed three theories that connect to changes in cognitive development. Below is a summary table reviewing each theories stance in how changes occur and how variation is considered.

Table Comparative Summary of Three Cognitive Theories

| Theme | Piaget | Information Processing | Vygotsky |

| Nature-Nurture | Maturation and experience = Nature and nurture |

Not emphasized | Environmental factors interact with biological structures= Nurture on nature |

| Continuous-Discontinuous | Discontinuous= Stages | Usually continuous | Continuous |

| Culture? | Not really | Not emphasized | Critical component |

| Individual diff.? | Universal stages | Not really but does explain variation | Yes |

Language Development (Ob 8)

Vocabulary growth: A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of 2 to 6 from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages such as Chinese and Japanese as well as those speaking English tend to learn nouns more readily. However, those learning less verb-friendly languages such as English seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai et al., 2008). Children are also very creative in creating their own words to use as labels such as a “nei-nei” for horse or “clopster” for lobster.

Literal meanings: Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice. But they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, two preschool-aged girls began to laugh loudly while listening to a tape-recording of Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” when the narrator reports, “Prince Phillip lost his head!” They imagine his head popping off and rolling down the hill as he runs and searches for it. Or a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children began asking “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization: Children learn rules of grammar as they learn language but may apply these rules inappropriately at first. For instance, a child learns to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense. They form a sentence such as “I goed there. I doed that.” This is typical at ages 2 and 3. They will soon learn new words such as went and did to be used in those situations. It would seem that the child has solidly learned the grammar rule, but it is actually common for the developing child to revert back to their original mistake. This happens as they overregulate the rule. This can happen because they intuitively discover the rule and overgeneralize it or because they are explicitly taught to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense in school. A child who had previously produced correct sentences may start to form incorrect sentences such as, “I goed there. I doed that.” These children are able to quickly re-learn the correct exceptions to the -ed rule, and it is a sign of their language learning.

The Impact of Training: Remember Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development? Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations, and encourage elaboration. The child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” and the adult responds, “You went there? Say, ‘I went there.’ Where did you go?” Children may be ripe for language as Chomsky suggests, but active participation in helping them learn is important for language development as well. The process of scaffolding (Vygotsky’s theory) is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.

Early Literacy

Phonological awareness, learning the sound system of a language, is the foundation for literacy, the ability to read, write, and understand information. Early literacy is enhanced by robust vocabulary development, phonological awareness, print awareness, and comprehension skills. Thus, children who have strong early literacy skills are more likely to enjoy academic success (Ramsook et al., 2020).

Parents and caregivers can support early literacy by reading to children regularly, supporting a text-rich environment with books and writing materials, and engaging in conversations and activities like storytelling and singing that promote language development. The repetition found in books and songs reinforces semantics, syntax, and grammar, and will promote a positive attitude towards reading. Reading books also furthers children’s exposure to a wider range of vocabulary than they might hear in everyday speech and conversations.

Although research has extensively explored older children’s use of tablets for reading, currently there is only limited understanding of the impact of digital reading in the early stages of literacy development. One review compared the impact of interactive, enhanced e-books (that is, with embedded dictionaries) to that of print books and non-enhanced, non-interactive e-books on the literacy skills of young children (López-Escriban et al., 2021). Most of the books in the study were carefully chosen by teachers for artistic and literary quality. The analysis revealed that when high-quality material is used, both enhanced and non-enhanced e-books are either equal to or have an advantage over print books in promoting phonological awareness and vocabulary learning. These findings have positive implications for marginalized populations, including those at risk of learning disabilities and those from lower SES families, and offer another alternative to standardized school-based instruction.

Psychosocial Development in Early Childhood: A Look at Self-Concept, Gender Identity, and Family Life

Self-Concept (Ob 11)

Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. Self-concept is our self-description according to various categories, such as our external and internal qualities. In contrast, self-esteem is an evaluative judgment about who we are. The emergence of cognitive skills in this age group results in improved perceptions of the self. If asked to describe yourself to others you would likely provide some physical descriptors, group affiliation, personality traits, behavioral quirks, and important values and beliefs. When researchers ask young children the same open-ended question, the children provide physical descriptors, preferred activities, and favorite possessions. Typically, a self-concept for a three-year-old will include basic vital facts such as their name, gender, and age. Thus, a 3-year-old might describe herself as a 3-year-old girl with red hair, who likes to play with Legos. This focus on external qualities is referred to as the categorical self. However, even children as young as 3 know there is more to themselves than these external characteristics. arter and Pike (1984) challenged the method of measuring personality with an open-ended question as they felt that language limitations were hindering the ability of young children to express their self-knowledge. They suggested a change to the method of measuring self-concept in young children, whereby researchers provide statements that ask whether something is true of the child (e.g., “I like to boss people around,” “I am grumpy most of the time”). Consistent with Harter and Pike’s suspicions, those in early childhood answer these statements in an internally consistent manner, especially after the age of 4 (Goodvin et al., 2008) and often give similar responses to what others (parents and teachers) say about the child (Brown et al., 2008; Colwell & Lindsey, 2003). Around age four, children may start to include new information in their self-concept, such as their interests and hobbies. One child may say they like Batman and coloring books, whereas another may mention dancing and the color yellow. However, at age four, these components are based on concrete, factual statements and are not evaluative. Starting around age five or six, some children might start to evaluate their skills internally, but expressing this view outwardly as part of their self-concept is still rare and will usually start later in childhood (Putnick et al., 2020).

Young children tend to have a generally positive self-image. When asked whether they perform better than, worse than, or about the same as other children when it comes to running, coloring, singing, or dancing, most four-year-olds rate themselves as performing better than others (Marsh et al., 2002; Orth et al., 2018). The reason is that at four years of age, most children are not yet able to fully consider the performance of others to make objective comparisons. Instead, they are most familiar with their own perspective and performance, and being satisfied with their abilities, they rate their own skills highly.

Herbert Mead (1967) explains how we develop a social sense of self by being able to see ourselves through the eyes of others. There are two parts of the self: the “I self” which is the part of the self that is spontaneous, creative, innate, and is not concerned with how others view us and the “me self” or the social definition of who we are. When we are born, we are all “I” and act without concern about how others view us. But the socialized self begins when we are able to consider how one important person views us. This initial stage is called “taking the role of the significant other.” For example, a child may pull a cat’s tail and be told by his mother, “No! Don’t do that, that’s bad” while receiving a slight slap on the hand. Later, the child may mimic the same behavior toward the self and say aloud, “No, that’s bad” while patting his own hand. What has happened? The child is able to see himself through the eyes of the mother. As the child grows and is exposed to many situations and rules of culture, he begins to view the self in the eyes of many others through these cultural norms or rules. This is referred to as “taking the role of the generalized other” and results in a sense of self with many dimensions. The child comes to have a sense of self as a student, as a friend, as a son, and so on.

Around five years of age, children start to become more self-conscious and are better able to evaluate and assess the way they are perceived by others. In many countries, including the United States, this coincides with the beginning of formal education. In a school setting, children may start to notice that some children are better at different activities, and perhaps they themselves are not the fastest or the best at everything. In the first year of formal education, children tend to experience an adjustment to their self-esteem, leading them to place less reliance on praise from parents and more on the social comparisons they make with other children (Pinto et al., 2015). It is typical to see self-esteem decline a little in the first year of formal education as children begin to have more realistic perceptions of themselves. For example, they may transform from believing they are “the highest jumper ever” to observing that they jump about as high as their peers in physical education class.

Self-Control

Self-control is not a single phenomenon but is multi-faceted. It includes response initiation, the ability to not initiate a behavior before you have evaluated all of the information, response inhibition, the ability to stop a behavior that has already begun, and delayed gratification, the ability to hold out for a larger reward by forgoing a smaller immediate reward (Dougherty et al., 2005). It is in early childhood that we see the start of self-control, a process that takes many years to fully develop. In the now classic “Marshmallow Test” (Mischel et al., 1972) children are confronted with the choice of a small immediate reward (immediate gratification) (a marshmallow) and a larger delayed reward (more marshmallows). Walter Mischel and his colleagues over the years have found that the ability to delay gratification at the age of 4 predicted better academic performance and health later in life (Mischel et al., 2011). The Marshmallow Test connects to children’s development of self-control and motivation. Self-control is related to executive function (term discussed earlier in the chapter). As executive function improves, children become less impulsive (Traverso et al., 2015) and self-regulate emotions, attention, and behavior.

Erikson: Initiative vs. Guilt (Ob 9)

By age three, the child begins stage 3: initiative versus guilt. The trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take initiative or to think of ideas and initiate action. Children are curious at this age and start to ask questions so that they can learn about the world. Parents should try to answer those questions without making the child feel like a burden or implying that the child’s question is not worth asking. Children may want to build a fort with the cushions from the living room couch or open a lemonade stand in the driveway or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Or they may just want to get themselves ready for bed without any assistance. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being critical of messes or mistakes. Soggy washrags and toothpaste left in the sink pales in comparison to the smiling face of a 5-year-old that emerges from the bathroom with clean teeth and pajamas!

During this time, children are taking initiative but also may desire having set routines. Many young children desire consistency and may be upset if there are changes to their daily routines. They may like to line up their toys or other objects or place them in symmetric patterns. Many young children have a set bedtime ritual and a strong preference for certain clothes, toys or games. All these tendencies tend to wane as children approach middle childhood, and the familiarity of such ritualistic behaviors seem to bring a sense of security and a general reduction in childhood fears and anxiety (Evans et al., 1999; Evans & Leckman, 2015).