Chapter 6: Middle Childhood

Objectives:

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- Describe physical growth during middle childhood.

- Prepare recommendations to avoid health risks in school-aged children.

- Define and apply conservation, reversibility, and identity in concrete operational intelligence.

- Explain changes in processing during middle childhood according to information processing theory of memory.

- Characterize language development in middle childhood.

- Compare preconventional, conventional, and postconventional moral development.

- Describe sexual development in middle childhood.

- Define and describe communication disorders and learning disabilities.

- Evaluate the impact of labeling on children’s self-concept and social relationships.

- Apply the ecological systems model to explore children’s experiences in schools.

- Examine social relationships in middle childhood.

- Analyze the impact of family structure on children’s development.

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Introduction

Middle childhood is the period of life that begins when children enter school and lasts until they reach adolescence. For the purposes of this text and this chapter, we will define middle childhood as ages 6 through 12. Think for a moment about children this age that you may know. What are their lives like? What kinds of concerns do they express and with what kinds of activities are their days filled? If it were possible, would you want to return to this period of life? Why or why not? Early childhood and adolescence seem to get much more attention than middle childhood. Compared to early childhood, children spend much more time in schools, with friends, and in structured activities. It may be easy for parents to lose track of their children’s development unless they stay directly involved in these worlds. Yet, children enter middle childhood still looking very young, and end the stage on the cusp of adolescence. Most children have gone through a growth spurt that makes them look more grown-up. The obvious physical changes are accompanied by changes in the brain. While we don’t see the actual brain changing, we can see the effects of the brain changes in the way that children in middle childhood play sports, write, and play games. It is important to stop and give full attention to middle childhood to stay in touch and to take notice of the varied influences on their lives in a larger world.

Physical Development: A Healthy Time (Ob 1)

Growth Rates and Motor Skills

Rates of growth generally slow during these years. Typically, a child will gain about 5-7 pounds a year and grow about 2 inches per year. They also tend to slim down and gain muscle strength and lung capacity making it possible to engage in strenuous physical activity for long periods of time. Around ages six to eight, the groundwork for puberty is being set by greater production of hormones from the adrenal glands (Mendle et al., 2019). These hormones prepare the body for physical maturation. There are not many sex differences at this point. Around age seven, children average 44 inches tall and 50 pounds, but by age eleven, girls average 52 inches tall and 82 pounds, and boys average 52 inches tall and 77 pounds. Towards the end of middle childhood, as girls enter puberty, which typically occurs a few years earlier than boys, they tend to be larger than boys of the same age. The onset of true puberty, including changes in physical characteristics like voice changes and increased body hair, does not occur until later, between eight and thirteen years of age for girls and between nine and fourteen years of age for boys (Farello et al., 2020). Puberty typically lasts between 2.5 and 4 years (Cheng et al., 2019).

Rates of growth generally slow during these years. Typically, a child will gain about 5-7 pounds a year and grow about 2 inches per year. They also tend to slim down and gain muscle strength and lung capacity making it possible to engage in strenuous physical activity for long periods of time. Around ages six to eight, the groundwork for puberty is being set by greater production of hormones from the adrenal glands (Mendle et al., 2019). These hormones prepare the body for physical maturation. There are not many sex differences at this point. Around age seven, children average 44 inches tall and 50 pounds, but by age eleven, girls average 52 inches tall and 82 pounds, and boys average 52 inches tall and 77 pounds. Towards the end of middle childhood, as girls enter puberty, which typically occurs a few years earlier than boys, they tend to be larger than boys of the same age. The onset of true puberty, including changes in physical characteristics like voice changes and increased body hair, does not occur until later, between eight and thirteen years of age for girls and between nine and fourteen years of age for boys (Farello et al., 2020). Puberty typically lasts between 2.5 and 4 years (Cheng et al., 2019).

Several factors may influence how quickly children grow, including genetics and environmental factors. Genes determine about 80 percent of adult height, while the other 20 percent is influenced by environmental factors (Perkins et al., 2016). A lack of protein in the diet and childhood disease are particularly important environmental influences on height (Bozzoli et al., 2009; Koletzko et al., 2014). Nutritional deficits can lead to stunted growth, which often persists and can get worse if malnourishment continues (Kitsao-Wekulo et al., 2013). Furthermore, stunted growth in school-aged children is often associated with other concerns, including behavior problems and cognitive deficits (Hoddinott et al., 2013). Other environmental factors include prenatal development resources (such as maternal nutrition), severe neglect (Nelson et al., 2019), and even the family’s socioeconomic status (SES) or the wealth of the country or region they live in (Fox & Heaton, 2012; Mumm et al., 2016). For example, children in wealthier countries, living in more urban areas, or from families with better economic and educational resources often are physically healthier and have better nutrition outcomes (Fox & Heaton, 2012; Mumm et al., 2016).

Brain Growth: The brain reaches its adult size at about age 7. Two major brain growth spurts occur during middle/late childhood (Spreen et al., 1995). Between ages 6 and 8, significant improvements in fine motor skills and eye-hand coordination are noted. Then between 10 and 12 years of age, the frontal lobes become more developed and improvements in logic, planning, and memory are evident (van der Molen & Molenaar, 1994). The location of the most significant changes in brain development is the prefrontal cortex, the most forward portion of the frontal lobe (Kolk & Rakic, 2022). This area is responsible for tasks such as logic, planning, memory, and attention. As you have learned, various environmental experiences play a role in shaping brain development. The school-aged child can is better able to plan, coordinate activity using both left and right hemispheres of the brain, and to control emotional outbursts.

Myelination is one factor responsible for these growths. From age 6 to 12, the nerve cells in the association areas of the brain, that is those areas where sensory, motor, and intellectual functioning connect, become almost completely myelinated (Johnson, 2005). This myelination contributes to increases in information processing speed and the child’s reaction time. The hippocampus, responsible for transferring information from the short-term to long-term memory, also shows increases in myelination resulting in improvements in memory functioning (Rolls, 2000).

Motor skills: One result of the slower rate of physical growth is an improvement in motor skills. Children of this age tend to sharpen their abilities to perform both gross motor skills such as riding a bike and fine motor skills such as cutting their fingernails. In gross motor skills (involving large muscles) boys typically outperform girls, while with fine motor skills (small muscles) girls outperform the boys. These improvements in motor skills are related to brain growth and experience during this developmental period. For example, some studies have shown increased fine motor dexterity among children who play video games (Adams et al., 2012). Culture is also an important factor that influences the development of motor skills. For example, children from Hong Kong, who often have early exposure to and practice with writing utensils and chopsticks, have more advanced fine motor skills than children from the United States (Chui et al., 2007). Differences by culture or gender are often due to differences in childrearing practices and in the timing and amount of exposure to certain skills that children receive.

Loosing teeth: Deciduous teeth, commonly known as milk teeth, baby teeth, primary teeth, and temporary teeth, are the first set of teeth in the growth development of humans. The primary teeth are important for the development of the mouth, development of the child’s speech, for the child’s smile, and play a role in chewing of food, Most children lose their first tooth around age 6, then continue to lose teeth for the next 6 years. In general, children lose the teeth in the middle of the mouth first and then lose the teeth next to those in sequence over the 6-year span. By age 12, generally all of the teeth are permanent teeth, however, it is not extremely rare for one or more primary teeth to be retained beyond this age, sometimes well into adulthood, often because the secondary tooth fails to develop.

Organized Sports: Pros and Cons (Ob 2)

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports. And in fact, many parents do. Approximately 26.5% of kids in the U.S. play soccer (Solomon, 2024). This activity promises to help children build social skills, improve athletically, and learn a sense of competition. It has been suggested, however, that the emphasis on competition and athletic skill can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, it appears that children’s activities are no longer children’s activities once adults become involved and approach the games as adults rather than children. The U. S. Soccer Federation recently advised coaches to reduce the amount of drilling engaged in during practice and to allow children to play more freely and to choose their own positions. The hope is that this will build on their love of the game and foster their natural talents.

Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children

- Improved physical and emotional development

- Better academic performance

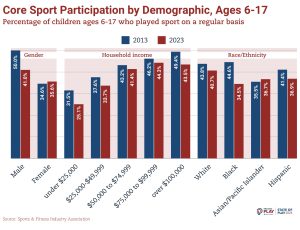

Yet, studies on children’s sports in the United States has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports (Sabo & Veliz, 2008, Aspen Institute, 2024). Girls were more likely to have never participated in any type of sport, although 34% of girls ages 6-12 regularly played sports in 2023 (Solomon, 2024).

Sabo and Veliz also found that fathers may not be providing their daughter’s as much support as they do their sons. While boys rated their fathers as their biggest mentor who taught them the most about sports, girls rated coaches and physical education teachers as their key mentors. Additionally, they found that children in suburban neighborhoods had a much higher participation of sports than boys and girls living in rural or urban centers. Several studies have found that when coaches receive proper training the drop-out rate is about 5% instead of the usual 30% (Fraser-Thomas et al., 2005; SPARC, 2013).

Since 2008 there has also been a downward trend in the number of sports children are engaged in, despite a body of research evidence that suggests that specializing in only one activity can increase the chances of injury while playing multiple sports is protective (SPARC, 2016). A University of Wisconsin study found that 49% of athletes who specialized in a sport experienced an injury compared with 23% of those who played multiple sports (McGuine, 2016).

E-games: In a SPARC (2016) report on the “State of Play” in the United States highlights a new technology trend. One in four children between the ages of 5 and 16 rate playing computer games with their friends as a form of exercise, known as exergames. Exergames are being considered as a potential tool for increasing physical activity, especially for children who may not enjoy traditional sports or physical education classes.

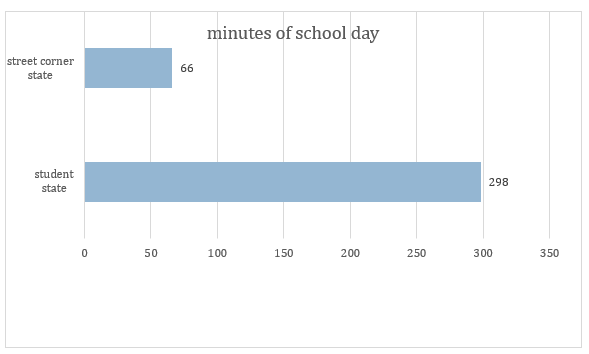

Physical Education: For many children, physical education in school is a key component in introducing children to sports. After years of schools cutting back on physical education programs, there has been a turnaround, prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and the related health issues. Despite these changes, currently, only the state of Oregon and the District of Columbia meet PE guidelines of a minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity in elementary school and 150-225 minutes in middle school (Perna et al, 2024).

Link to Learning

Designed for parents with children ages 6–12, this video about physical activity for children discusses the importance of regular physical activity, how much physical activity children need, and how to get children moving.

Childhood Obesity (Ob 2)

The decreased participation in school physical education and youth sports is just one of many factors that has led to an increase in children being overweight or obese. The current measurement for determining excess weight is the Body Mass Index (BMI) which expresses the relationship of height to weight. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), children’s whose BMI is at or above the 85th percentile for their age are considered overweight, while children who are at or above the 95th percentile are considered obese (Lu, 2016). Approximately 12.7% of 2-5-year-olds were considered overweight or obese, and 20.7% of 6 to 11-year-olds were overweight or obese (CDC, 2020). Excess weight and obesity in children are associated with a variety of medical and cognitive conditions including high blood pressure, insulin resistance, inflammation, depression, and lower academic achievement (Lu, 2016). Being overweight has also been linked to impaired brain functioning, which includes deficits in executive functioning, working memory, mental flexibility, and decision making (Liang et al., 2014). Children who ate more saturated fats performed worse on relational memory tasks while eating a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids promoted relational memory skills (Davidson, 2014). Using animal studies Davidson et al. (2013) found that large amounts of processed sugars and saturated fat weakened the blood-brain barrier, especially in the hippocampus. This can make the brain more vulnerable to harmful substances that can impair its functioning. Another important executive functioning skill is controlling impulses and delaying gratification. Children who are overweight show less inhibitory control than normal-weight children, which may make it more difficult for them to avoid unhealthy foods (Lu, 2016). Overall, being overweight as a child increases the risk of cognitive decline as one ages.

A growing concern is the lack of recognition from parents that children are overweight or obese. Katz (2015) referred to this as “Oblivobesity.” Black et al. (2015) found that parents in the United Kingdom (UK) only recognized their children as obese when they were above the 99.7th percentile while the official cut-off for obesity is at the 85th percentile. Oude et al. (2010) surveyed 439 parents and found that 75% of parents of overweight children said the child had a normal weight and 50% of parents of obese children said the child had a normal weight. For these parents, overweight was considered normal and obesity was considered normal or a little heavy. Doolen et al. (2009) reported on several studies from the United Kingdom, Australia, Italy, and the United States, and in all locations, parents were more likely to misperceive their children’s weight. Black et al. (2015) concluded that as the average weight of children rises, what parents consider normal also rises.

Being overweight can be a lifelong struggle. If parents cannot identify if their children are overweight they will not be able to intervene and assist their children with proper weight management. An added concern is that the children themselves are not accurately identifying if they are overweight. In a United States sample of 8-15-year-olds, more than 80% of overweight boys and 70% of overweight girls misperceived their weight as normal (Sarafrazi et al., 2014). Also noted was that as the socioeconomic status of the children rose, the frequency of these misconceptions decreased. It appeared that families with more resources were more conscious of what defines a healthy weight.

Children who are overweight tend to be rejected, ridiculed, teased, and bullied by others (Stopbullying.gov, 2018). This can certainly be damaging to their self-image and popularity. In addition, obese children run the risk of suffering orthopedic problems such as knee injuries, and they have an increased risk of heart disease and stroke in adulthood (Lu, 2016). It is hard for a child who is obese to become a non-obese adult. In addition, the number of cases of pediatric diabetes has risen dramatically in recent years.

Recommendations: Dieting is not really the answer. If you diet, your basal metabolic rate tends to decrease thereby making the body burn even fewer calories in order to maintain the weight. Increased activity is much more effective in lowering weight and improving the child’s health and psychological well-being.

In 2018 the American Psychological Association (APA) developed a clinical practice guideline that recommends family-based, multicomponent behavioral interventions to treat obesity and overweight in children 2 to 18 (Weir, 2019). The guidelines recommend counseling on diet, physical activity and “teaching parents strategies for goal setting, problem-solving, monitoring children’s behaviors, and modeling positive parental behaviors,” (p. 32).

Behavioral interventions, including training children to overcome impulsive behavior, are being researched to help overweight children (Lu, 2016). Practicing inhibition has been shown to strengthen the ability to resist unhealthy foods. Parents can help their overweight children the best when they are warm and supportive without using shame or guilt. Parents can also act like the child’s frontal lobe until it is developed by helping them make correct food choices and praising their efforts (Liang et al., 2014).

Research also shows that exercise, especially aerobic exercise, can help improve cognitive functioning in overweight children (Lu, 2016). Exercise reduces stress and being an overweight child, subjected to the ridicule of others can certainly be stressful. Parents should take caution against emphasizing diet alone to avoid the development of an obsession about dieting that can lead to eating disorders. Instead, increasing a child’s activity level is most helpful.

APA has also recommended that behavioral treatment could be delivered in primary care offices to encourage greater participation. It is also a community effort as APA additionally recommend that schools and communities need to offer more nutritious meals to children and limit sodas and unhealthy foods.

Health Concerns in Middle Childhood

Asthma is a life-long, chronic lung disease that causes inflammation in the airways, making it difficult to breathe. Asthma is a serious public health problem globally (WHO, 2024). It affects about 8 percent of children in the United States (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2017). Although there is no known single cause of asthma, a child is more likely to have asthma if other family members have asthma, if they have other allergic conditions, if they live in urban areas or areas with high air pollution, and if they have obesity (WHO, 2024). Avoiding common triggers of asthma, including air pollution and allergies, can reduce the symptoms of asthma such as shortness of breath and tightness in the chest (McCarthy, 2022). Although it can typically be medically managed, uncontrolled asthma is one of the leading causes of school absences among children and can also interfere with sleep and physical activity (Qin et al., 2022).

Diabetes, a metabolic disorder, is another chronic health issue that can have significant effects on child development. Until recently, most cases in children were type 1 diabetes, a disease in which the immune system attacks healthy tissue and results in the body not producing enough insulin to get glucose or sugar into the cells. However, type 2 diabetes, which used to be considered “adult-onset diabetes,” is increasing among children and is often preventable. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes include excess weight, inactivity, and having a family history which leads to increase insulin resistance (CDC, 2022). Although both types of diabetes can be managed, diabetes and other chronic illnesses in childhood have been linked to increased behavior problems and socioemotional concerns in children (Lupini et al., 2023). Many of the behavioral and socioemotional risks for children with chronic illnesses such as diabetes may be prevented through careful monitoring and treatment of symptoms.

Sexual Development (Ob 7)

Once children enter grade school (approximately ages 7–12), their awareness of social rules increases and they become more modest and want more privacy, particularly around adults. Although self-touch (masturbation) and sexual play continue, children at this age are likely to hide these activities from adults. Curiosity about adult sexual behavior increases—particularly as puberty approaches—and children may begin to seek out sexual content in television, movies, and printed material. Telling jokes and “dirty” stories is common. Children approaching puberty are likely to start displaying romantic and sexual interest in their peers.

Although parents often become concerned when a child shows sexual behavior, such as touching another child’s private parts, these behaviors are not uncommon in developing children. Most sexual play is an expression of children’s natural curiosity and should not be a cause for concern or alarm.

Table. Expectations for sexual behaviors in middle childhood.

In general, “typical” childhood sexual play and exploration:

|

Table. Basic information, and Safety information for sexual behaviors in middle childhood.

| Basic Information to each middle age children about sexuality (NCTSN, 2009) | Safety Information to share with middle age children (NCTSN, 2009) |

|

|

Cognitive Development (Ob 3, Ob 4, Ob 5)

Recall from the last chapter that children in early childhood are in Piaget’s preoperational stage, and during this stage, children are learning to think symbolically about the world. Cognitive skills continue to expand in middle and late childhood as thought processes become more logical and organized when dealing with concrete information. Children at this age understand concepts such as past, present, and future, giving them the ability to plan and work toward goals. Additionally, they can process complex ideas such as addition and subtraction and cause-and-effect relationships.

Concrete Operational Thought (Ob3)

From ages 7 to 11, children are in what Piaget referred to as the Concrete Operational Stage of cognitive development (Crain, 2005). This involves mastering the use of logic in concrete ways. The word concrete refers to that which is tangible; that which can be seen, touched, or experienced directly. The concrete operational child is able to make use of logical principles in solving problems involving the physical world. For example, the child can understand the principles of cause and effect, size, and distance.

The child can use logic to solve problems tied to their own direct experience but has trouble solving hypothetical problems or considering more abstract problems. The child uses inductive reasoning, which is a logical process in which multiple premises believed to be true are combined to obtain a specific conclusion. For example, a child has one friend who is rude, another friend who is also rude, and the same is true for a third friend. The child may conclude that friends are rude. We will see that this way of thinking tends to change during adolescence being replaced with deductive reasoning.

Table. Inductive versus deductive reasoning

| Inductive Reasoning | Deductive Reasoning |

|

|

We will now explore some of the major abilities that the concrete child exhibits.

Classification: As children’s experiences and vocabularies grow, they build schemata and are able to organize objects in many different ways. They also understand classification hierarchies and can arrange objects into a variety of classes and subclasses.

Object constancy or identity: The concrete child understands that objects have qualities that do not change even if the object is altered in some way. For instance, the mass of an object does not change by rearranging it. A piece of chalk is still chalk even when the piece is broken in two.

Reversibility: The child learns that some things that have been changed can be returned to their original state. Water can be frozen and then thawed to become liquid again. But eggs cannot be unscrambled. Arithmetic operations are reversible as well: 2 + 3 = 5 and 5 – 3 = 2. Many of these cognitive skills are incorporated into the school’s curriculum through mathematical problems and in worksheets about which situations are reversible or irreversible.

Conservation: Remember the example in our last chapter of preoperational children thinking that a tall beaker filled with 8 ounces of water was “more” than a short, wide bowl filled with 8 ounces of water? Concrete operational children can understand the concept of conservation which means that changing one quality (in this example, height, or water level) can be compensated for by changes in another quality (width). Consequently, there is the same amount of water in each container, although one is taller and narrower and the other is shorter and wider.

Decentration: Concrete operational children no longer focus on only one dimension of an object (such as the height of the glass) and instead consider the changes in other dimensions too (such as the width of the glass). This allows for conservation to occur.

Seriation: Arranging items along a quantitative dimension, such as length or weight, in a methodical way, is now demonstrated by the concrete operational child. For example, they can methodically arrange a series of different-sized sticks in order by length, while younger children approach a similar task in a haphazard way.

These new cognitive skills increase the child’s understanding of the physical world, however, according to Piaget, they still cannot think in abstract ways. Additionally, they do not think in systematic scientific ways. For example, when asked which variables influence the period that a pendulum takes to complete its arc, and given weights they can attach to strings in order to do experiments, most children younger than 12 perform biased experiments from which no conclusions can be drawn (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958).

Piaget’s Theory Revisited

In many ways, Piaget’s description of the concrete operational stage has held up well to scrutiny. However, there are differences in how children demonstrate concrete operational skills across the world. Subsequent cross-cultural research studying areas including Bali, Indonesia, India, and Nepal, found that the sequence of stages is generally the same across cultures, and the cognitive processes within those stages are the same (Dasen, 2022). Additionally, some children show aspects of concrete operational thought before the age of seven, which is earlier than Piaget believed it first appeared (McGarrigle & Donaldson, 1974). Children can achieve earlier understanding of some operations, such as conservation, when they are specifically exposed to tasks in which adults demonstrate them (Dasen, 2022). On the other hand, another study found that many children may reach Piaget’s stages later than they did thirty years ago (Flynn & Shayer, 2018), which may be due to drops in education budgets and in the overall quality of education in many countries. Despite these criticisms, Piaget’s theory offers a window into the many cognitive advancements that happen during middle childhood.

Piaget’s approach to cognitive development among school-aged children has had a tremendous impact on education (Zhang, 2022). Many schools use his principles to determine how to educate children and when to introduce concepts such as addition and subtraction. Many schools also provide students with opportunities to learn through active learning, such as building a volcano in science class, rather than just reading about volcanos. However, despite this understanding of the importance of active learning for children, we are seeing increases in the amount of time that children engage with screens, even in school settings (Muppalla et al., 2023). Screen media use is associated with poorer academic performance, along with other potential adverse effects on development.

Information Processing Theory (Ob 4)

Children differ in their memory abilities, and these differences predict both their readiness for school and academic performance in school (PreBler et al., 2013). During middle and late childhood, school-aged children can process information more accurately and rapidly and are more efficient at retaining that information than they were during early childhood. They also show significant gains in

- their ability to determine what information to attend to,

- their ability to attend to information for longer periods,

- their grasp of how their memory works, and

- their use of strategies to improve retention and recall.

Both changes in the brain and experience foster these abilities.

Working Memory: The capacity of working memory expands during middle and late childhood, and research has suggested that both an increase in processing speed and the ability to inhibit irrelevant information from entering memory are contributing to the greater efficiency of working memory during this age (de Ribaupierre, 2002). Changes in myelination and synaptic pruning in the cortex are likely behind the increase in processing speed and ability to filter out irrelevant stimuli (Kail et al., 2013). Children with learning disabilities in math and reading often have difficulties with working memory (Alloway, 2009). They may struggle with following the directions of an assignment. When a task calls for multiple steps, children with poor working memory may miss steps because they may lose track of where they are in the task. Adults working with such children may need to communicate: Using more familiar vocabulary, using shorter sentences, repeating task instructions more frequently, and breaking more complex tasks into smaller more manageable steps. Some studies have also shown that more intensive training of working memory strategies, such as chunking, aid in improving the capacity of working memory in children with poor working memory (Alloway et al., 2013).

Attention: As noted above the ability to inhibit irrelevant information improves during this age group, with there being a sharp improvement in selective attention from age six into adolescence (Vakil et al., 2009). Children also improve in their ability to shift their attention between tasks or different features of a task (Carlson et al, 2013). A younger child who is asked to sort objects into piles based on the type of object, car versus animal, or color of the object, red versus blue, may have difficulty if you switch from asking them to sort based on type to now having them sort based on color. This requires them to suppress the prior sorting rule. An older child has less difficulty making the switch, meaning there is greater flexibility in their attentional skills. These changes in attention and working memory contribute to children having more strategic approaches to challenging tasks.

Encoding and Memory Strategies: The process of transferring information from short-term/working memory to long-term memory is called encoding. Middle childhood is when children begin using more effective encoding strategies to improve their ability to move information from short-term/working memory to long-term memory (Bjorklund et al, 2008). Encoding strategies include rehearsing items, grouping items into categories, and spending more time studying harder items rather than easy ones. Children can start using these strategies around five to six years of age, but they are able to use them more efficiently around age seven, after which this ability continues to increase through age ten (Schneider et al., 2009). Children continue to use more complex encoding strategies as they move through middle childhood. Some of the more frequently used memory strategies are rehearsal, elaboration, and organization.

Memory Strategies: Bjorklund (2005) describes a developmental progression in the acquisition and use of memory strategies. Such strategies are often lacking in younger children but increase in frequency as children progress through elementary school. Examples of memory strategies include rehearsing the information you wish to recall, visualizing and organizing information, creating rhymes, such “i” before “e” except after “c,” or inventing acronyms, such as “ROYGBIV” to remember the colors of the rainbow. Schneider et al. (2009) reported a steady increase in the use of memory strategies from ages six to ten in their longitudinal study. Moreover, by age ten many children were using two or more memory strategies to help them recall information. Schneider and colleagues found that there were considerable individual differences at each age in the use of strategies and that children who utilized more strategies had better memory performance than their same-aged peers.

Table. Example Memory Strategies

| Memory Strategy | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Rehearsal | Practicing to learn new information | Children repeat a vocabulary word over and over to learn it for a vocabulary quiz. |

| Elaboration | Connecting new information to existing knowledge | Children help with baking at home and may recognize fractions in math class from the recipes they have used. |

| Organization | Arranging bits of information in an ordered manner, such as using groups or categories | Children learn the acronym “ROY G BIV” to help remember the order of the colors in the spectrum. |

Children may experience three deficiencies in their use of memory strategies.

- A mediation deficiency occurs when a child does not grasp the strategy being taught, and thus, does not benefit from its use. If you do not understand why using an acronym might be helpful, or how to create an acronym, the strategy is not likely to help you.

- In a production deficiency, the child does not spontaneously use a memory strategy and has to be prompted to do so. In this case, the child knows the strategy and is more than capable of using it, but they fail to “produce” the strategy on their own. For example, a child might know how to make a list but may fail to do this to help them remember what to bring on a family vacation.

- A utilization deficiency refers to a child using an appropriate strategy, but it fails to aid their performance. Utilization deficiency is common in the early stages of learning a new memory strategy (Schneider & Pressley, 1997; Miller, 2000).

Until the use of the strategy becomes automatic it may slow down the learning process, as space is taken up in memory by the strategy itself. Initially, children may get frustrated because their memory performance may seem worse when they try to use the new strategy. Once children become more adept at using the strategy, their memory performance will improve. Sodian and Schneider (1999) found that new memory strategies acquired prior to age eight often show utilization deficiencies with there being a gradual improvement in the child’s use of the strategy. In contrast, strategies acquired after this age often followed an “all-or-nothing” principle in which improvement was not gradual, but abrupt.

Knowledge Base: During middle and late childhood, children are able to learn and remember due to an improvement in the ways they attend to and store information. As children enter school and learn more about the world, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. One significant reason is that they continue to have more experiences on which to tie new information. In other words, their knowledge base, knowledge in particular areas that makes learning new information easier, expands (Berger, 2014).

Metacognition: Children in middle and late childhood also have a better understanding of how well they are performing a task, and the level of difficulty of a task. As they become more realistic about their abilities, they can adapt to studying strategies to meet those needs. Young children spend as much time on an unimportant aspect of a problem as they do on the main point, while older children start to learn to prioritize and gauge what is significant and what is not. As a result, they develop metacognition. Metacognition refers to the knowledge we have about our own thinking and our ability to use this awareness to regulate our own cognitive processes (Bruning et al., 2004).

Kazemi et al. (2012) compared school-aged boys who learned chess for 6-months and a control group. They found that chess players showed more achievement in both meta-cognitive abilities and mathematical problem-solving capabilities than other non-chess players. Children’s’ meta-cognitive ability and their mathematical problem-solving power were also positively correlated. Based on this study, perhaps chess is an effective tool for developing higher order thinking skills.

Critical Thinking: According to Bruning et al. (2004) there is a debate in U.S. education as to whether schools should teach students what to think or how to think. Critical thinking, or a detailed examination of beliefs, courses of action, and evidence, involves teaching children how to think. The purpose of critical thinking is to evaluate information in ways that help us make informed decisions. Critical thinking involves better understanding a problem through gathering, evaluating, and selecting information, and also by considering many possible solutions. Ennis (1987) identified several skills useful in critical thinking. These include: Analyzing arguments, clarifying information, judging the credibility of a source, making value judgments, and deciding on an action. Metacognition is essential to critical thinking because it allows us to reflect on the information as we make decisions.

Executive Functions: Executive function includes the cognitive skills we need to control or self-regulate our behavior and to work toward goals. They include skills such as working memory and attentional control, and others such as inhibition, problem-solving, self-control, mental flexibility, and planning and organization. Executive functions begin to develop during the preschool years but continue to mature through middle childhood and into adolescence. In fact, middle childhood is an important period for the development of executive functions because of the increasing social and academic demands associated with formal schooling. These skills are closely tied to maturation of the prefrontal cortex in the brain that is taking place during the preadolescent years, and they are also influenced by the presence of warm and responsive parents and by cognitively stimulating environments (Bourrier et al., 2018; Fay-Stammbach et al., 2014). Executive functions are also associated with school readiness, academic achievement, and social behavior (Poon, 2018). Thus, schools or intervention programs that target executive functions may see significant rewards as children use those skills to be successful in academic and social settings.

Theory of Mind: Another cognitive ability related to frontal lobe functioning and executive functions is theory of mind: the awareness of your own mental states and the understanding that others have thoughts, beliefs, and perspectives different from your own. Theory of mind was discussed in previous chapter, it continues to develop for the next several years. Children are increasingly able to predict what others are thinking and feeling and develop an understanding of complex mental abilities from various perspectives. Theory of mind is likely associated with better relationships with peers and teachers which may increase school engagement, higher levels of reading comprehension (because they understand the message that the author is intending to convey and the minds of the characters in the texts that they read (Kim, 2017), and with scientific reasoning. Children who understand the minds of others are better able to create and evaluate hypotheses (Kyriakopoulou & Vosniadou, 2020). There are individual differences in the development of theory of mind. For example, children diagnosed with some developmental disabilities, including autism spectrum disorder and social anxiety disorder, often have deficits in theory of mind (Spek et al., 2010; Washburn et al., 2016). Cultural differences also exist. Children in collectivist cultures like China and India tend to recognize later than children in individualistic cultures like the United States and Australia that others have different beliefs and opinions (Shahaeian et al., 2011). A recent systematic review of studies on cultural variations in theory of mind and related constructs such as empathy and perspective-taking indicated that cross-cultural differences in language use, cultural values, and parenting styles may lead to differences in development of these skills (Aival-Naveh et al., 2019). A likely reason is that individualistic cultures emphasize recognizing differences in opinions, thoughts, and beliefs more than collectivist cultures do.

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development (Ob 6)

Lawrence Kohlberg (1963) built on the work of Piaget and was interested in finding out how our moral reasoning changes as we get older. He wanted to find out how people decide what is right and what is wrong. In order to explore this area, he read a story containing a moral dilemma to boys of different age groups. In the story, a man is trying to obtain an expensive drug that his wife needs in order to treat her cancer. The man has no money and no one will loan him the money he requires. He begs the pharmacist to reduce the price, but the pharmacist refuses. So, the man decides to break into the pharmacy to steal the drug. Then Kohlberg asked the children to decide whether the man was right or wrong in his choice. Kohlberg was not interested in whether they said the man was right or wrong, he was interested in finding out how they arrived at such a decision. He wanted to know what they thought made something right or wrong.

Preconventional moral development: The youngest subjects seemed to answer based on what would happen to the man as a result of the act. For example, they might say the man should not break into the pharmacy because the pharmacist might find him and beat him. Or they might say that the man should break in and steal the drug and his wife will give him a big kiss. Right or wrong, both decisions were based on what would physically happen to the man as a result of the act. This is a self-centered approach to moral decision-making. He called this most superficial understanding of right and wrong preconventional moral development.

Conventional moral developmen: Middle childhood boys seemed to base their answers on what other people would think of the man as a result of his act. For instance, they might say he should break into the store, and then everyone would think he was a good husband. Or, he shouldn’t because it is against the law. In either case, right and wrong are determined by what other people think. A good decision is one that gains the approval of others or one that complies with the law. This he called conventional moral development.

Postconventional moral development: Older children were the only ones to appreciate the fact that this story has different levels of right and wrong. Right and wrong are based on social contracts established for the good of everyone or on universal principles of right and wrong that transcend the self and social convention. For example, the man should break into the store because, even if it is against the law, the wife needs the drug and her life is more important than the consequences the man might face for breaking the law. Or, the man should not violate the principle of the right of property because this rule is essential for social order. In either case, the person’s judgment goes beyond what happens to the self. It is based on a concern for others; for society as a whole or for an ethical standard rather than a legal standard. This level is called post-conventional moral development because it goes beyond convention or what other people think to a higher, universal ethical principle of conduct that may or may not be reflected in the law. Notice that such thinking (the kind supreme justices do all day in deliberating whether a law is moral or ethical, etc.) requires being able to think abstractly. Often this is not accomplished until a person reaches adolescence or adulthood.

Table. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development

| Age | Moral Level Description |

| Young children usually prior to age 9 | Preconventional morality |

| Stage 1: Focus is on self-interest and punishment is avoided. The man shouldn’t steal the drug, as he may get caught and go to jail. Stage 2: Rewards are sought. A person at this level will argue that the man should steal the drug because he does not want to lose his wife who takes care of him. |

|

| Older children, adolescents, and most adult’s | Conventional morality |

| Stage 3: Focus is on how situational outcomes impact others and wanting to please and be accepted. The man should steal the drug because that is what good husbands do. Stage 4: People make decisions based on laws or formalized rules. The man should obey the law because stealing is a crime. |

|

| Rare with adolescents and few adults | Postconventional morality |

| Stage 5: Individuals employ abstract reasoning to justify behaviors. The man should steal the drug because laws can be unjust and you have to consider the whole situation. Stage 6: Moral behavior is based on self-chosen ethical principles. The man should steal the drug because life is more important than property. |

|

Consider your own decision-making processes. What guides your decisions? Are you primarily concerned with your personal well-being? Do you make choices based on what other people will think about your decision? Or are you guided by other principles? To what extent is this approach guided by your culture?

Consider your own decision-making processes. What guides your decisions? Are you primarily concerned with your personal well-being? Do you make choices based on what other people will think about your decision? Or are you guided by other principles? To what extent is this approach guided by your culture?

Criticisms of Kohlberg’s theory: Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment and social rules and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, people may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems, but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms, such as respect for authority, may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). In addition, there is frequently little correlation between how we score on the moral stages and how we behave in real life. Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of males better than it describes that of females. Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence for a gender difference in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000).

Language Development (Ob 5)

Vocabulary

One of the reasons that children can classify objects in so many ways is that they have acquired a vocabulary to do so. By 5th grade, a child’s vocabulary has grown to 40,000 words. It grows at the rate of 20 words per day, a rate that exceeds that of preschoolers. This language explosion, however, differs from that of preschoolers because it is facilitated by being able to associate new words with those already known and because it is accompanied by a more sophisticated understanding of the meanings of a word.

New Understanding

As children get older, they become more aware of the qualities of language and can think about and evaluate language, a skill known as metalinguistic awareness (Simard & Gutiérrez, 2017). The child is also able to think of objects in less literal ways. For example, of asked for the first word that comes to mind when one hears the word “pizza”, the preschooler is likely to say “eat” or some word that describes what is done with a pizza. However, the school-aged child is more likely to place pizza in the appropriate category and say “food” or “carbohydrate.” They also begin to understand that one word can have multiple meanings. For example, duck can refer to an animal or an action. This new ability is one of the reasons children begin to appreciate humor, puns, and eventually sarcasm. For example, in the preceding vignette, Troy loves jokes. He might enjoy one like this: “What did Baby Corn say to Mama Corn? Answer: Where is Popcorn?”

The child is also able to think of objects in less literal ways. For example, of asked for the first word that comes to mind when one hears the word “pizza”, the preschooler is likely to say “eat” or some word that describes what is done with a pizza. However, the school-aged child is more likely to place pizza in the appropriate category and say “food” or “carbohydrate.”

Grammar and Flexibility: School-aged children are also able to learn new rules of grammar with more flexibility. While preschoolers are likely to be reluctant to give up saying “I goed there”, school-aged children will learn this rather quickly along with other rules of grammar.

While the preschool years might be a good time to learn a second language (being able to understand and speak the language), the school years may be the best time to be taught a second language (the rules of grammar).

Pragmatics: (Social) Pragmatics is the way we use language in different social contexts, and a useful tool for developing social relationships with others. It requires understanding 1) how to use language for different functions such as requesting something, telling a story, or conveying knowledge, 2) how to use written language differently across contexts such as text messages versus emails or writing an essay for school, 3) how to change language to meet the needs of listeners as different as a grandparent and a friend, or to speak up in a noisy room, and 4) the “hidden” rules of conversation such as taking turns and using eye contact, body gestures, and facial expressions. The use of pragmatics during middle childhood also includes code-switching, which refers to using more than one form of language within a single conversation. Although

Bilingualism: Although monolingual speakers often do not realize it, the majority of children around the world are Bilingual, meaning that they understand and use two languages (Meyers-Sutton, 2005). Many children around the world grow up in multilingual households, where more than one language is spoken. In the United States, approximately 26 percent of children are multilingual, a relatively low rate compared to other areas such as Singapore (90 percent), Europe (67 percent), and Canada (55 percent) although multilingualism is increasing in the United States (Luk, 2017; Wu et al., 2020). It varies quite a bit from state to state, with California having the highest rates at 43 percent and West Virginia the lowest, around 2 percent (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018). U.S. multilingual children speak a total of more than 100 different languages, but approximately 75 percent speak Spanish and English (Dietrich & Hernandez, 2022).

Children who are bilingual must become adept at regularly switching between languages (Tulloch & Erika, 2023), a speech style called multilingual code-switching (or translanguaging). Multilingual code-switching requires competency in at least two languages and is associated with strongly identifying with two cultures (Yim & Clément, et al., 2021). While some children learn multiple languages at the same time beginning at birth, others may learn one language in their early years and then add a second. In this case it takes longer to master the second language than it does if both languages are learned at the same time (Paradis, 2023).

Recent research suggests that any disadvantages associated with being bilingual are erased by its numerous advantages (Dentella et al., 2024). These include better executive functioning, memory, selective attention, and analytical reasoning (Nguyen et al., 2023; Planckaert et al., 2023). For example, children who speak multiple languages have better cognitive control because they must inhibit one language while they use another. They also have better metalinguistic skills than children who only speak one language. For example, children who are bilingual can understand grammatical rules more easily than children who speak a single language. There are also social benefits to multilingualism, such as being able to participate in diverse communities (Djonov, 2019).

The student who speaks both languages fluently has a definite cognitive advantage. As you might suspect and research confirmed, a fully fluent bilingual student is in a better position to express concepts or ideas in more than one way, and to be aware of doing so (Jimenez et al., 2006). Unfortunately, the bilingualism of many students is unbalanced in the sense that they are either still learning English, or else they have lost some earlier ability to use their original, heritage language. Losing one’s original language is a concern as research finds that language loss limits students’ ability to learn English as well or as quickly as they could do. Having a large vocabulary in a first language has been shown to save time in learning vocabulary in a second language (Hansen et al., 2002). Preserving the first language is important if a student has impaired skill in all languages and therefore needs intervention or help from a speech-language specialist. Research has found, in such cases, that the specialist can be more effective if the specialist speaks and uses the first language as well as English (Kohnert et al., 2005).

What are the advantages to having a bilingual (or multilingual) brain? Watch this TED Talk by Educator Mia Nacamulli about how our brains benefit from knowing more than one language to learn more.

Approaches to Bilingualism in Schools

In larger communities throughout the United States, it is common for a single classroom to contain students from several language backgrounds at once. In classrooms, as in other social settings, bilingualism exists in different forms and degrees. At one extreme are students who speak both English and another language fluently; at the other extreme are those who speak only limited versions of both languages. In between are students who speak their home (or heritage) language much better than English, as well as others who have partially lost their heritage language in the process of learning English (Tse, 2001). Commonly, a student may speak a language satisfactorily, but be challenged by reading or writing it. Whatever the case, each bilingual student poses unique challenges to teachers.

Children tend to learn new languages more easily than adults (Ghasemi & Hashemi, 2011). This may be partly because they are more willing to use the language without fear of making errors or because their brains have more neural plasticity or flexibility (Birdsong, 2017). In addition, non-native speakers who learned a language before the age of 10 are often difficult to distinguish from a native speaker of that language (Ghasemi & Hashemi, 2011). For this reason, childhood is often referred to as a critical period for the acquisition of a second language (Birdsong, 2017). Even adolescents up to age 17 or 18 can learn the grammar structure of a new language more easily than adults (Hartshorne et al., 2018).

Communication Disorders (Ob 8)

At the end of early childhood, children are often assessed in terms of their ability to speak properly. By first grade, about 5% of children have a notable speech disorder (Medline Plus, 2016c).

Fluency disorders: Fluency disorders affect the rate of speech. Speech may be labored and slow, or too fast for listeners to follow. The most common fluency disorder is stuttering. Stuttering is a speech disorder in which sounds, syllables, or words are repeated or last longer than normal. These problems cause a break in the flow of speech, which is called dysfluency (Medline Plus, 2016b). About 5% of young children, aged 2 to 5, will develop some stuttering that may last from several weeks to several years (Medline Plus, 2016c). Approximately 75% of children recover from stuttering. For the remaining 25%, stuttering can persist as a lifelong communication disorder (National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders, NIDCD, 2016). This is called developmental stuttering and is the most common form of stuttering. Brain injury, and in very rare instances, emotional trauma may be other triggers for developing problems with stuttering. In most cases of developmental stuttering, other family members share the same communication disorder. Researchers have recently identified variants in four genes that are more commonly found in those who stutter (NIDCD, 2016).

Articulation disorder: An articulation disorder refers to the inability to correctly produce speech sounds (phonemes) because of imprecise placement, timing, pressure, speed, or flow of movement of the lips, tongue, or throat (NIDCD, 2016). Sounds can be substituted, left off, added, or changed. These errors may make it hard for people to understand the speaker. They can range from problems with specific sounds, such as lisping to severe impairment in the phonological system. Most children have problems pronouncing words early on while their speech is developing. However, by age 3, at least half of what a child says should be understood by a stranger. By age 5, a child’s speech should be mostly intelligible. Parents should seek help if by age six the child is still having trouble producing certain sounds. It should be noted that accents are not articulation disorders (Medline Plus, 2016a).

Voice disorders: Disorders of the voice involve problems with pitch, loudness, and quality of the voice (American Speech-Language and Hearing Association, 2016). It only becomes a disorder when problems with the voice make the child unintelligible. In children, voice disorders are significantly more prevalent in males than in females. Between 1.4% and 6% of children experience problems with the quality of their voice. Causes can be due to structural abnormalities in the vocal cords and/or larynx, functional factors, such as vocal fatigue from overuse, and in rarer cases psychological factors, such as chronic stress and anxiety.

Developmental Problems (Ob 8)

Children’s cognitive and social skills are evaluated as they enter and progress through school. Sometimes this evaluation indicates that a child needs special assistance with language or in learning how to interact with others. Evaluation and diagnosis of a child can be the first step in helping to provide that child with the type of instruction and resources needed. But diagnosis and labeling also have social implications. It is important to consider that children can be misdiagnosed and that once a child has received a diagnostic label, the child, teachers, and family members may tend to interpret actions of the child through that label. The label can also influence the child’s self-concept. Consider, for example, a child who is misdiagnosed as learning disabled. That child may expect to have difficulties in school, lack confidence, and out of these expectations, have trouble indeed. This self-fulfilling prophecy or tendency to act in such a way as to make what you predict will happen comes true, calls our attention to the power that labels can have whether or not they are accurately applied. It is also important to consider that children’s difficulties can change over time; a child who has problems in school may improve later or may live under circumstances as an adult where the problem (such as a delay in math skills or reading skills) is no longer relevant. That person, however, will still have a label as learning disabled. It should be recognized that the distinction between abnormal and normal behavior is not always clear; some abnormal behavior in children is fairly common. Misdiagnosis may be more of a concern when evaluating learning difficulties than in cases of autism spectrum disorder where unusual behaviors are clear and consistent.

Learning Disabilities (Ob8)

Ability means we are all on a continuum between not at all able and easily able, and our ability level can change over time. While there is a spectrum of abilities, a child who has impairment that interferes with learning may be classified as having a learning disability. A Learning Disability (or LD) is a specific impairment of academic learning that interferes with a specific aspect of schoolwork and that reduces a student’s academic performance significantly. In other words, a child with a learning disability has problems in a specific area or with a specific task or type of activity related to education. An LD shows itself as a major discrepancy between a student’s ability and some feature of achievement: The student may be delayed in reading, writing, listening, speaking, or doing mathematics, but not in all of these at once. A learning problem is not considered a learning disability if it stems from physical, sensory, or motor handicaps, or from generalized intellectual impairment. It is also not an LD if the learning problem really reflects the challenges of learning English as a second language. Genuine LDs are the learning problems left over after these other possibilities are accounted for or excluded. Typically, a student with an LD has not been helped by teachers’ ordinary efforts to assist the student when he or she falls behind academically, though what counts as an “ordinary effort,” of course, differs among teachers, schools, and students. Most importantly, though, an LD relates to a fairly specific area of academic learning. A student may be able to read and compute well enough, for example, but not be able to write. LDs are by far the most common form of special educational need, accounting for half of all students with special needs in the United States and anywhere from 5 to 20 percent of all students, depending on how the numbers are estimated (United States Department of Education, 2005; Ysseldyke & Bielinski, 2002). Students with LDs are so common, in fact, that most teachers regularly encounter at least one per class in any given school year, regardless of the grade level they teach.

These difficulties are identified in school because this is when children’s academic abilities are being tested, compared, and measured. Consequently, once academic testing is no longer essential in that person’s life (as when they are working rather than going to school) these disabilities may no longer be noticed or relevant, depending on the person’s job and the extent of the disability.

Learning disabilities are connected to reading, writing, or math: dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia. The following table describes each.

Table. Examples of Learning Disabilities connected to reading, writing, or math

| Dyslexia | one of the most commonly diagnosed disabilities and involves having difficulty in the area of reading. This diagnosis is used for a number of reading difficulties. Common characteristics are a difficulty with phonological processing, which includes the manipulation of sounds, spelling, and rapid visual/verbal processing. Additionally, the child may reverse letters, have difficulty reading from left to right, or may have problems associating letters with sounds. It appears to be rooted in neurological problems involving the parts of the brain active in recognizing letters, verbally responding, or being able to manipulate sounds. Recent studies have identified a number of genes that are linked to developing dyslexia (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2016). Treatment typically involves altering teaching methods to accommodate the person’s particular problematic area.

|

| Dysgraphia | a writing disability is often associated with dyslexia (Carlson, 2013). There are different types of dysgraphia, including phonological dysgraphia when the person cannot sound out words and write them phonetically. Orthographic dysgraphia is demonstrated by those individuals who can spell regularly spelled words, but not irregularly spelled ones. Some individuals with dysgraphia experience difficulties in motor control and experience trouble forming letters when using a pen or pencil.

|

| Dyscalculia | refers to problems in math. Cowan and Powell (2014) identified several terms used when describing difficulties in mathematics including dyscalculia, mathematical learning disability, and mathematics disorder. All three terms refer to students with average intelligence who exhibit poor academic performance in mathematics. When evaluating a group of third graders, Cowan and Powell (2014) found that children with dyscalculia demonstrated problems with working memory, reasoning, processing speed, and oral language, all of which are referred to as domain-general factors. Additionally, problems with multi-digit skills, including number system knowledge, were also exhibited.

|

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) shows a constant pattern of inattention and/or hyperactive and impulsive behavior that interferes with normal functioning (American Psychological Association (APA), 2013). Some of the signs of inattention include great difficulty with, and avoidance of, tasks that require sustained attention (such as conversations or reading), failure to follow instructions (often resulting in failure to complete school work and other duties), disorganization (difficulty keeping things in order, poor time management, sloppy and messy work), lack of attention to detail, becoming easily distracted, and forgetfulness. Hyperactivity is characterized by excessive movement, and includes fidgeting or squirming, leaving one’s seat in situations when remaining seated is expected, having trouble sitting still (e.g., in a restaurant), running about and climbing on things, blurting out responses before another person’s question or statement has been completed, difficulty waiting one’s turn for something, and interrupting and intruding on others. Frequently, the hyperactive child comes across as noisy and boisterous. The child’s behavior is hasty, impulsive, and seems to occur without much forethought; these characteristics may explain why adolescents and young adults diagnosed with ADHD receive more traffic tickets and have more automobile accidents than do others their age (Thompson et al., 2007). Table 2 shows three ways it can present itself based on which symptoms are most problematic

Table 2. ADHD Presentations

| ADHD Presentation | Description |

|---|---|

| Predominately inattentive | Child has difficulty following instructions, paying attention to details, and organizing or finishing a task. |

| Predominately hyperactive-impulsive | Child displays excessive fidgeting and talking, difficulty sitting for longer period of times, and restlessness. Has trouble with impulsivity and difficulty waiting their turn or listening to instructions. |

| Combined presentation | Child has symptoms of both predominately inattentive and predominately hyperactive-impulsive forms. |

ADHD occurs in approximately 5 percent of children between three and twelve years of age (Salari et al., 2023), a rate that has increased over the past several decades. It’s likely that actual cases have not been rising, but that teachers, parents, and medical professionals are more aware of and more likely to recognize the symptoms and refer children for a diagnosis. Diagnostic techniques and screening processes have also improved, making it easier to diagnose a child (Abdelnour et al., 2022).

Signs of hyperactivity in children with ADHD include excessive movement, fidgeting, squirming, difficulty remaining seated, and talkativeness (Ayano et al. 2023). Children with ADHD do not have any intellectual impairments when compared to children without ADHD, but they may struggle in school because of their difficulties with executive functioning. Children with ADHD face severe academic and social challenges. Compared to their non-ADHD counterparts, children with ADHD have lower grades and standardized test scores and higher rates of expulsion, grade retention, and dropping out (Loe & Feldman, 2007; Iines et al., 2023). They also are less well-liked and more often rejected by their peers (Hoza et al., 2005).

Boys are three times more likely than girls to be diagnosed with ADHD (Reuben & Elgaddal, 2024). Boys with ADHD are also more likely to display externalizing behaviors such as increased running and impulsivity, whereas girls are more likely to show internalizing behaviors such as low-self-esteem and inattentiveness. The externalizing behaviors are more likely to be disruptive at home or at school and may explain, in part, why boys are more likely to be diagnosed (Mowlem et al., 2019). However, if all children in a community are screened, gender differences in the diagnosis of ADHD disappear (Assari, 2021) supporting the idea that higher rates of ADHD are due to more noticeable symptoms.

ADHD can persist into adolescence and adulthood (Barkley et al., 2002). A recent study found that 29.3% of adults who had been diagnosed with ADHD decades earlier still showed symptoms (Barbaresi et al., 2013). Somewhat troubling, this study also reported that nearly 81% of those whose ADHD persisted into adulthood had experienced at least one other comorbid disorder, compared to 47% of those whose ADHD did not persist. Additional concerns when an adult has ADHD include worse educational attainment, lower socioeconomic status, less likely to be employed, more likely to be divorced, and more likely to have non-alcohol-related substance abuse problems (Klein et al., 2012).

Causes of ADHD: There are several possible causes for ADHD including genetics, preterm birth and maternal use of substances like acetaminophen during pregnancy (Banaschewski et al., 2017; Ji et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Sourander et al., 2019). More than seventy-six potential risk genes have been identified for ADHD (Demontis et al., 2023) and many of these are important for the regulation of the neurotransmitter dopamine. There is also research that has linked structures in the brain to ADHD. Brain imaging studies have shown that children with ADHD exhibit abnormalities in their frontal lobes, an area in which dopamine is in abundance. Compared to children without ADHD, those with ADHD appear to have smaller frontal lobe volume, and they show less frontal lobe activation when performing mental tasks. Recall that one of the functions of the frontal lobes is to inhibit our behavior. Thus, abnormalities in this region may go a long way toward explaining the hyperactive, uncontrolled behavior of ADHD. Most of these studies have focused on the frontal lobe and the prefrontal cortex, and suggest that the frontal lobe is less developed in individuals with this diagnosis (Hoogman et al., 2019). Since the frontal lobe is responsible for executive functions, attention, impulse control and planning, delays in frontal lobe development explain many of the behaviors seen in children with this disorder.

Importantly, despite widely held beliefs, there is no evidence that sugar consumption is related to increased hyperactivity (Kramer, 2023) and, although, food additives have been shown to increase hyperactivity, the overall impact is very small (McCann et al., 2007). Many parents attribute their child’s hyperactivity to sugar. A statistical review of 16 studies, however, concluded that sugar consumption has no effect at all on the behavioral and cognitive performance of children (Wolraich et al., 1995). Additionally, although food additives have been shown to increase hyperactivity in non-ADHD children, the effect is rather small (McCann et al., 2007). Numerous studies, however, have shown a significant relationship between exposure to nicotine in cigarette smoke during the prenatal period and ADHD (Linnet et al., 2003). Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with the development of more severe symptoms of the disorder (Thakur et al., 2013).

Treatment for ADHD: Recommended treatment for ADHD includes behavioral interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, parent and teacher education, recreational programs, and lifestyle changes, such as getting more sleep (Clay, 2013). For some children, medication is prescribed. Parents are often concerned that stimulant medication may result in their child acquiring a substance use disorder. However, research using longitudinal studies has demonstrated that children diagnosed with ADHD who received pharmacological treatment had a lower risk for substance abuse problems than those children who did not receive medication (Wilens et al., 2003). The risk of substance abuse problems appears to be even greater for those with ADHD who are un-medicated and also exhibit antisocial tendencies (Marshal & Molina, 2006).

Education (Ob 10)

Remember the ecological systems model (Urie Brofenbrenner) that we explored in chapter one? This model helps us understand an individual by examining the contexts in which the person lives and the direct and indirect influences on that person’s life. School becomes a very important component of children’s lives during middle and late childhood, and parents and the culture contribute to children’s experiences in school as indicated by the ecological systems model through their interaction with the school.

Parental Involvement in School: Parents vary in their level of involvement with their children’s schools. Teachers often complain that they have difficulty getting parents to participate in their child’s education and devise a variety of techniques to keep parents in touch with daily and overall progress. For example, parents may be required to sign a behavior chart each evening to be returned to school or may be given information about the school’s events through websites and newsletters. There are other factors that need to be considered when looking at parental involvement. To explore these, first, ask yourself if all parents who enter the school with concerns about their child be received in the same way? If not, what would make a teacher or principal more likely to consider the parent’s concerns? What would make this less likely? Lareau and Horvat (2004) found that teachers seek a particular type of involvement from particular types of parents. While teachers thought they were open and neutral in their responses to parental involvement, in reality, teachers were most receptive to support, praise and agreement coming from parents who were most similar in race and social class with the teachers. Parents who criticized the school or its policies were less likely to be given voice. Parents who have higher levels of income, occupational status, and other qualities favored in society have family capital. This is a form of power that can be used to improve a child’s education. Parents who do not have these qualities may find it more difficult to be effectively involved. Lareau and Horvat (2004) offer three cases of African-American parents who were each concerned about discrimination in the schools. Despite evidence that such discrimination existed, their children’s white, middle-class teachers were reluctant to address the situation directly.

Note the variation in approaches and outcomes for these three families:

- The Masons: This working class, an African-American couple, a minister and a beautician, voiced direct complaints about discrimination in the schools. Their claims were thought to undermine the authority of the school and as a result, their daughter was kept in a lower reading class. However, her grade was boosted to “avoid a scene” and the parents were not told of this grade change.

- The Irving’s: This middle class, African-American couple was concerned that the school was discriminating against black students. They fought against it without using direct confrontation by staying actively involved in their daughter’s schooling and making frequent visits to the school to make sure that discrimination could not occur. They also talked with other African-American teachers and parents about their concerns.