Chapter 9: Early Adulthood

Objectives:

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to…

- Discuss the developmental tasks of early adulthood.

- Describe physical development in early adulthood.

- Explain how early adulthood is a healthy, yet risky time of life.

- Distinguish between formal and postformal thought.

- Describe Erikson’s stage of intimacy vs. isolation.

- Question Erikson’s assertion about the focus on intimacy in early adulthood.

- Identify trends in mate selection, age at first marriage, and cohabitation in the United States.

- Discuss fertility issues in early adulthood.

- Explain social exchange theory of mate selection.

- Define the principle of least interest.

- Apply Sternberg’s theory of love to specific examples of relationships.

- Apply Lee’s love styles to specific examples of relationships.

- Compare frames of relationships.

- Explain the wheel theory of love.

- Explain the process of disaffection.

- Explain the stages of career development.

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Introduction

For the purpose of this text and this chapter, we define early adulthood as ages 25 to 40. With the elongation of adolescence and the introduction of emerging adulthood, we can stay “younger” for longer now. Ask your parents and grandparents on what they were doing at age 25 and compare that with today’s youth. Chances are, there will be some major differences with major milestones being delayed.

Developmental Tasks of Early Adulthood (Ob 1)

Early adulthood can be a very busy time of life. Havighurst (1972) describes some of the developmental tasks of young adults. They identified developmental tasks across the lifespan into 6 different stages. These tasks are typically encountered by most people in the culture where the individual belongs. The tasks for young adulthood include:

- Achieving autonomy: trying to establish oneself as an independent person with a life of one’s own

- Establishing identity: more firmly establishing likes, dislikes, preferences, and philosophies

- Developing emotional stability: becoming more stable emotionally which is considered a sign of maturing

- Establishing a career: deciding on and pursuing a career or at least an initial career direction and pursuing an education

- Finding intimacy: forming first close, long-term relationships

- Becoming part of a group or community: young adults may, for the first time, become involved with various groups in the community. They may begin voting or volunteering to be part of civic organizations (scouts, church groups, etc.). This is especially true for those who participate in organizations as parents.

- Establishing a residence and learning how to manage a household: learning how to budget and keep a home maintained.

- Becoming a parent and rearing children: learning how to manage a household with children. Making marital adjustments and learning to parent.

Some of these tasks connect to processing in emerging adulthood whereas Havighurst would emphasize establishment of these tasks during this time frame. To what extent do you think these tasks have changed in the last several years? How might these tasks be different across cultures?

Some of these tasks connect to processing in emerging adulthood whereas Havighurst would emphasize establishment of these tasks during this time frame. To what extent do you think these tasks have changed in the last several years? How might these tasks be different across cultures?

Physical Development (Ob 2)

By the time we reach early adulthood, our physical maturation is complete, although our height and weight may increase slightly. As mentioned in chapter 8, in our twenties are probably at the peak of their physiological development (physiological peak), including muscle strength, reaction time, sensory abilities, and cardiac functioning. Most professional athletes are at the top of their game during this stage, and many women have children in the early-adulthood years (Boundless, 2016).

Facing the Physiological Peak: People in their mid-twenties and thirties are considered young adults. After the physiological peak, one’s reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity start to decline as the aging process actually begins during early adulthood. These systems will now start a slow, gradual decline so that by the time you reach your mid to late 30s, you will begin to notice signs of aging. This includes a decline in your immune system, your response time, and in your ability to recover quickly from physical exertion. Around the age of 30, many changes begin to occur in different parts of the body. For example, the lens of the eye starts to stiffen and thicken, resulting in changes in vision (usually affecting the ability to focus on close objects). Sensitivity to sound decreases; this happens twice as quickly for men as for women. Hair can start to thin and become gray around the age of 35, although this may happen earlier for some individuals and later for others. The level of collagen, a substance that helps keep skin firm and elastic, peaks at 25 and slowly declines afterwards (Reilly & Lozano, 2021). The skin becomes drier and wrinkles start to appear by the end of early adulthood. Although bones continue to build until age 30 to 35 years old, the skeletal bone mass of women is almost complete by the age of 20 (CDC, 2021). If you acquire high bone mass as a young adult, you’re more able to sustain that bone mass until late in life. The quality and amount of synovial fluid, the lubricant keeping joints healthy, starts to show some minimal decline as early as age 28, which can lead to increased stiffness (Temple-Wong et al., 2016). For individuals who have had an injury, such as athletes or from an accident, post-traumatic arthritis osteoarthritis may also occur (Punzi et al., 2016). Changes includes a decline in response time (reaction time) and the ability to recover quickly from physical exertion. For example, you may have noticed that it takes you quite some time to stop panting after running to class or taking the stairs. After about the age of 35, it is normal for your lung function to decline gradually as you age. This can make breathing slightly more difficult as you get older (American Lung Association, n.d.) During the aging process, muscles like the diaphragm can get weaker, lung tissue that helps keep your airways open can lose elasticity (making airways can get a little smaller), and one’s rib cage bones can change and get smaller which leaves less room for your lungs to expand (American Lung Association, n.d.). The immune system also becomes less adept at fighting off illness, and women’s reproductive capacity starts to decline (Boundless, 2016).

But, here is more good news. Getting out of shape is not an inevitable part of aging; it is probably due to the fact that you have become less physically active and have experienced greater stress. How is that good news, you ask? It’s good news because it means that there are things you can do to combat many of these changes. For example, the muscle strength of men and women peaks anywhere from 20 to 30 years old. If you’re not suffering from injuries or disease, you can maintain this strength for another 20 years by engaging in strength training. Additionally, although a decrease in lung function is a normal part of the aging, there are steps you can take to stay as healthy as possible. Staying active and avoiding tobacco smoke are two things you can protect and even strengthen your lungs. So, keep in mind, as we continue to discuss the life span that many of the changes we associate with aging can be turned around if we adopt healthier lifestyles.

A Healthy, but Risky Time (Ob 3)

Doctors’ visits are less frequent in early adulthood than for those in midlife and late adulthood and are necessitated primarily by injury and pregnancy (Berger, 2005). However, among the top five causes of death in young adulthood are unintentional injury (including motor vehicle accidents), homicide, and suicide (Heron, & Smith, 2007). Cancer and heart disease complete the list. Rates of violent death (homicide, suicide, and accidents) are highest among young adult males and vary among by race and ethnicity. Rates of violent death are higher in the United States than in Canada, Mexico, Japan, and other selected countries. Males are three times more likely to die in auto accidents than are females (Frieden, 2011).

Substance Abuse: Rates of violent death are influenced by substance abuse which peaks during emerging adulthood. While illicit drug use peaks between the ages of 19 and 22, it declines in early adulthood (Berk, 2007). Additionally, 25% of those who smoke cigarettes, a third of those who smoke marijuana, and 70 percent of those who abuse cocaine began using after age 17 (Volkow, 2004). Some young adults use as a way of coping with stressors from family, personal relationships, or concerns over being on one’s own. Others use because they have friends who use and in the early 20s, there is still a good deal of pressure to conform. Half of all alcohol consumed in the United States is in the form of binge drinking (Frieden, 2011).

Sexual Responsiveness and Reproduction in Early Adulthood (Ob 8)

Sexual Responsiveness: Men and women tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. For men, sexual responsiveness tends to peak in the late teens and early twenties. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness begins a slow decline in the late twenties and into the thirties although a man may continue to be sexually active. Through time, a man may require more intense stimulation in order to become aroused. Women often find that they become more sexually responsive throughout their 20s and 30s and may peak in the late 30s or early 40s. This is likely due to greater self-confidence and reduced inhibitions about sexuality.

Reproduction: For many couples, early adulthood is the time for having children. However, delaying childbearing until the late 20s or early 30s has become more common in the United States. Couples delay childbearing for a number of reasons. Women are more likely to attend college and begin careers before starting families. And both men and women are delaying marriage until they are in their late 20s and early 30s.

Infertility: Infertility affects about 6.1 million women or 10 percent of the reproductive age population (American Society of Reproductive Medicine, 2000-2007). Male factors create infertility in about a third of the cases. For men, the most common cause is a lack of sperm production or low sperm production. Female factors cause infertility in another third of cases. For women, one of the most common causes of infertility is the failure to ovulate. Another cause of infertility is pelvic inflammatory disease, an infection of the female genital tract (Carroll, 2007). Pelvic inflammatory disease is experienced by 1 out of 7 women in the United States and leads to infertility about 20 percent of the time. One of the major causes of pelvic inflammatory disease is Chlamydia trachomatis, the most commonly diagnosed sexually transmitted infection in young women. Another cause of pelvic inflammatory disease is gonorrhea. Both male and female factors contribute to the remainder of cases of infertility.

Fertility treatment: The majority of infertility cases (85-90 percent) are treated using fertility drugs to increase ovulation or with surgical procedures to repair the reproductive organs or remove scar tissue from the reproductive tract. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is used to treat infertility in less than 5 percent of cases. IVF is used when a woman has blocked or deformed fallopian tubes or sometimes when a man has a very low sperm count. This procedure involves removing eggs from the female and fertilizing the eggs outside the woman’s body. The fertilized egg is then reinserted in the woman’s uterus. The average cost of IVF is over $12,000 and the success rate is between 5 to 30 percent. IVF makes up about 99 percent of artificial reproductive procedures.

Less common procedures include gamete intra-fallopian tube transfer (GIFT) which involves implanting both sperm and ova into the fallopian tube and fertilization is allowed to occur naturally. The success rate of implantation is higher for GIFT than for IVF (Carroll, 2007). Zygote intra-fallopian tube transfer (ZIFT) is another procedure in which sperm and ova are fertilized outside of the woman’s body and the fertilized egg or zygote is then implanted in the fallopian tube. This allows the zygote to travel down the fallopian tube and embed in the lining of the uterus naturally. This procedure also has a higher success rate than IVF.

As of September 2023, insurance coverage for infertility is required in 21 states, but the amount and type of coverage available vary greatly (ASRM, 2024). The majority of couples seeking treatment for infertility pay much of the cost. Consequently, infertility treatment is much more accessible to couples with higher incomes. However, grants and funding sources are available for lower-income couples seeking infertility treatment as well.

Cognitive Development (Ob 4)

Beyond Formal Operational Thought: Postformal Thought

In the adolescence chapter, we discussed formal operational thought. In early adulthood (and beyond), we are more likely to consider multiple perspectives. As discussed in chapter 8, his ability to bring together different perspectives is referred to as dialectical thought and is part of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). The hallmark for postformal thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances never directly experienced. Postformal thought is practical, realistic, and more individualistic. As a person approaches the late 30s, chances are they make decisions out of necessity or because of prior experience and are less influenced by what others think. Of course, this is particularly true in individualistic cultures such as the United States. As adults we also consider experiences and probabilities compared to adolescence. If you compare a 15-year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the later considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. Why the change? The adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. This difference in adult and adolescent thought can spark arguments between the generations. Here is an example. A student in her late 30s relayed such an argument she was having with her 14-year-old son. The son had saved a considerable amount of money and wanted to buy an old car and store it in the garage until he was old enough to drive. He could sit in it; pretend he was driving, clean it up, and show it to his friends. It sounded like a perfect opportunity. The mother, however, had practical objections. The car could just sit for several years without deteriorating. The son would certainly change his mind about the type of car he wanted before he was old enough to drive and they would be stuck with a car that would not run. Having a car nearby would be too much temptation and the son might decide to sneak it out for a quick run around the block, etc.

Psychosocial Development

Gaining Adult Status: Many of the developmental tasks of early adulthood involve becoming part of the adult world and gaining independence. Young adults sometimes complain that they are not treated with respect-especially if they are put in positions of authority over older workers. Consequently, young adults may emphasize their age to gain credibility from those who are even slightly younger. “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” a young adult might exclaim. (Note: This kind of statement is much less likely to come from someone in their 40s!).

The focus of early adulthood is often on the future. Many aspects of life are on hold while people go to school, go to work, and prepare for a brighter future. There may be a belief that the hurried life now lived will improve ‘as soon as I finish school’ or ‘as soon as I get promoted’ or ‘as soon as the children get a little older.’ As a result, time may seem to pass rather quickly. The day consists of meeting many demands that these tasks bring. The incentive for working so hard is that it will all result in a better future.

Erikson’s Theory (Ob 5,6)

Intimacy vs. Isolation: Erikson believed that the main task of early adulthood was to establish intimate relationships. Intimacy is emotional or psychological closeness and Erikson would describe as relationships that have honesty, closeness, and love. Erikson theorized that during this period, the major conflict centers on forming intimate, loving relationships with other people. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, but there are periods of identity crisis and stability. And having some sense of identity is essential for intimate relationships. Success at this stage leads to fulfilling relationships. People who are successful in resolving the conflict of the intimacy versus isolation stage are able to develop deep, meaningful relationships with others. They have close, lasting romantic relationships, as well as having strong relationships with family and friends. Failure, on the other hand, can result in feelings of loneliness and isolation. Those who struggle to form intimacy with others are often left feeling lonely and isolated. Some individuals may feel particularly lonely if they struggle to form close friendships with others.

Friendships as a source of intimacy: In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Tannen, 1990). Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussion problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care!

Friendships between men and women become more difficult because of the unspoken question about whether friendships will lead to romantic involvement. It may be acceptable to have opposite-sex friends as an adolescent, but once a person begins dating or marries; such friendships can be considered threatening. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with a couple of friends.

Partners as a source of intimacy: Dating, Cohabitation, and Mate Selection (Ob7)

Dating

In general, traditional dating among teens and those in their early twenties has been replaced with more varied and flexible ways of getting together. The Friday night date with dinner and a movie that may still be enjoyed by those in their 30s gives way to less formal, more spontaneous meetings that may include several couples or a group of friends. Two people may get to know each other and go somewhere alone. How would you describe a “typical” date? Who calls? Who pays? Who decides where to go? What is the purpose of the date? In general, greater planning is required for people who have additional family and work responsibilities. Teens may simply have to negotiate to get out of the house and to carve out time to be with friends.

Cohabitation or Living Together

How prevalent is cohabitation? Cohabitation is an arrangement made by two people who are not married but live together. Among 25-29 year-olds, cohabitation rates increased from 15.5% in 2012 to 19.0% in 2022 (Julian, 2024). According to a 2018 National Center for Health Statistics report, more than one-half of U.S. adults have cohabited at some point in their lives. The number of cohabiting couples in the United States today is over 10 times higher than it was in 1960. Indeed, from examining the National Survey for Family Growth that surveyed women 15-39 in several different cohorts show generational differences (Eckenmeyer & Manning, 2018). Millennial women (born 1980-1984) were 53% more likely to live with more than one romantic partner during young adulthood compared with the late Baby Boomers (born 1960-1964), even after taking into account sociodemographic characteristics such as race and ethnicity and educational level, and relationship characteristics such as their age when their first cohabiting relationship ended and whether they had children. Not only were early Millennial women more likely to live with more than one partner without marriage, they also formed subsequent cohabiting relationships more quickly than the late Baby Boomers—dropping from nearly four years between live-in relationships to just over two years.

Similar increases have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. In fact, more children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than to married couples. The lowest rates of cohabitation are in Ireland, Italy, and Japan (Benokraitis, 2005). It’s important to note that cohabitation rates can differ based on factors such as age, education level, and regional variations within countries. The global trend shows an overall increase in cohabitation among young adults, though specific rates vary significantly by country and culture.

How long do cohabiting relationships last? Cohabitation among younger adults tends to be short-lived. Relationships between older adults tend to last longer. Cohabitation tends to last longer in European countries than in the United States. Half of cohabiting relationships in the U.S. end within a year; only 10 percent last more than 5 years. Short-term cohabiting relationships (lasting a year or less) are more characteristics of people in their early 20s. The majority of people who cohabit are between the ages of 25-44, while about 9 percent of those who cohabit are under age 24 (7 percent 18-24 live with spouse).. Many of these couples eventually marry. Those who cohabit more than five years tend to be older and more committed to the relationship. Cohabitation may be preferable to marriage for a number of reasons. For partners over 65, cohabitation is preferable to marriage for practical reasons. For many of them, marriage would result in a loss of Social Security benefits and consequently is not an option. Others may believe that their relationship is more satisfying because they are not bound by marriage. Consider this explanation from a 62-year-old woman who was previously in a long-term, dissatisfying marriage. She and her partner live in New York but spend winters in South Texas at a travel park near the beach. “There are about 20 other couples in this park and we are the only ones who aren’t married. They look at us and say, ‘I wish we were so in love’. I don’t want to be like them” (Overstreet). Or another couple who have been happily cohabiting for over 12 years. Both had previously been in bad marriages that began as long-term, friendly, and satisfying relationships. But after marriage, these relationships became troubled marriages. These happily cohabiting partners stated that they believe that there is something about marriage that “ruins a friendship.”

Why do people cohabit? People cohabit for a variety of reasons. The largest number of couples in the United States engages in premarital cohabitation. These couples are testing the relationship before deciding to marry. About half of these couples eventually get married. The second most common type of cohabitation is dating cohabitation. These partnerships are entered into for fun or convenience and involve less commitment than premarital cohabitation. About half of these partners break up and about one-third eventually marry. Trial marriage is a type of cohabitation in which partners are trying to see what it might be like to be married. They are not testing the other person as a potential mate, necessarily; rather, they are trying to find out how being married might feel and what kinds of adjustments they might have to make. Over half of these couples split up. In substitute marriage, partners are committed to one another and are not necessarily seeking marriage. Forty percent of these couples continue to cohabit after 5 to 7 years (Bianchi & Casper, 2000). Certainly, there are other reasons people cohabit. Some cohabit out of a feeling of insecurity or to gain freedom from someone else (Ridley et al., 1978). And many cohabit because they cannot legally marry.

Same-Sex Couples: As of 2024, same-sex marriage is legal in 36 countries, and counting. Other states grant same-sex couples rights as domestic partners or recognize civil unions. Many other countries either recognize same-sex couples for the purpose of immigration, grant rights for domestic partnerships or grant common law marriage status to same-sex couples. Same-sex marriage is legal in Argentina, Belgium, Canada, Iceland, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, South Africa, Spain, Canada, and the Netherlands. Many other countries either recognize same-sex couples for the purpose of immigration, grant rights for domestic partnerships or grant common law marriage status to same-sex couples.

Same-sex couples struggle with concerns such as the division of household tasks, finances, sex, and friendships as do heterosexual couples. One difference between same-sex and heterosexual couples, however, is that same-sex couples have to live with the added stress that comes from social disapproval and discrimination. And continued contact with an ex-partner may be more likely among homosexuals and bisexuals because of the closeness of the circle of friends and acquaintances.

Mate-Selection (Ob9)

Contemporary young adults in the United States are waiting longer than before to marry. In 2017, the median age of first marriage was 27.4 for women and 29.5 for men (U.S. Census Bureau). This reflects a dramatic increase in the age of first marriage for women, but the age for men is similar to that found in the late 1800s. Marriage is being postponed for college and starting a family often takes place after a woman has completed her education and begun a career. However, the majority of women will eventually marry (Bianchi & Casper, 2000).

Social exchange theory, developed by sociologist George Homans (1961), suggests that people try to maximize rewards and minimize costs in social relationships. Each person entering the marriage market comes equipped with assets and liabilities or a certain amount of social currency with which to attract a prospective mate. In social encounters people weigh the potential benefits and risks of social relationships. Benefits may include social support, companionship, and pleasure being around the individual. Costs involve things that one perceives as negatives such as having to put money, time, and effort into a relationship. Relationships can be assessed and evaluated in terms of expectations. As one determines the value of the relationship, an evaluation is made if the benefits outweigh the potential costs. Positive relationship are those I which the benefits outweigh the costs while negative relationships occur when the costs are greater than the benefits. When the risks outweigh the rewards, people will terminate or abandon that relationship. For example, if you have a romantic partner always has to borrow money from you or you always are expected to pay for the bill, then this would be seen as a high cost. However, one may also see that the time spent with the individual is very rewarding – full of companionship, social support and enjoyment. Evaluation of one’s relationships are subject to change over time, as individuals continually take stock of what they have gained and lost in their relationships. This implies that relationships that a person found satisfying at one point in time may become dissatisfying later because of changes in perceived rewards and costs. This theory connects to friendships as well as romantic relationships.

A fair exchange (Ob 10)

Customers in the market for relationships do not look for a ‘good deal’, however. Rather, most look for a relationship that is mutually beneficial or equitable. One of the reasons for this is because most a relationship in which one partner has far more assets than the other will result if power disparities and a difference in the level of commitment from each partner. According to Waller’s principle of least interest, the partner who has the most to lose without the relationship (or is the most dependent on the relationship) will have the least amount of power and is in danger of being exploited. A greater balance of power, then, may add stability to the relationship.

Homogamy and the filter theory of mate selection: Societies specify through both formal and informal rules who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate within which groups we should marry. For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. These rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age and to a lesser extent, religion. Rules of exogamy specify the groups into which one is prohibited from marrying.

According to the filter theory of mate selection (Kerckhoff & Davis, 1962), the pool of eligible partners becomes narrower as it passes through filters used to eliminate members of the pool. One such filter is propinquity or geographic proximity. Mate selection in the United States typically involves meeting eligible partners face to face. Those with whom one does not come into contact are simply not contenders. Race and ethnicity is another filter used to eliminate partners. Although interracial dating has increased in recent years and interracial marriage rates are higher than before, interracial marriage still represents only 17 percent of all marriages in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Physical appearance is another feature considered when selecting a mate. Age, social class, and religion are also criteria used to narrow the field of eligible mates. Thus, the field of eligible mates becomes significantly smaller before those things we are most conscious of such as preferences, values, goals, and interests, are even considered.

Online Relationships: What impact does the internet have on the pool of eligible mates? There are hundreds of websites designed to help people meet. Some of these are geared toward helping people find suitable marriage partners and others focus on less committed involvements. Websites focus on specific populations-big beautiful women, Christian motorcyclists, parents without partners, and people over 50, etc. Theoretically, the pool of eligible mates is much larger as a result. However, many who visit sites are not interested in marriage; many are already married. And so if a person is looking for a partner online, the pool must be filtered again to eliminate those who are not seeking long-term relationships. While this is true in the traditional marriage market as well, knowing a person’s intentions and determining the sincerity of their responses becomes problematic online.

Online communication differs from face-to-face interaction in a number of ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues upon which to base their first impressions. A person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings all provide information in face-to-face meetings. But in computer-mediated meetings, written messages are the only cues provided. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement makes it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. It is easier to tell one’s secrets because there is little fear of loss. One can find a virtual partner who is warm, accepting, and undemanding (Gwinnell, 1998). And exchanges can be focused more on emotional attraction than physical appearance.

When online, people tend to disclose more intimate details about themselves more quickly. A shy person can open up without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. And someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships. None of the worries of home or work get in the way of the exchange. The partner can be given one’s undivided attention, unlike trying to have a conversation on the phone with a houseful of others or at work between duties. Online exchanges take the place of the corner café as a place to relax, have fun, and be you (Brooks, 1997). However, breaking up or disappearing is also easier. A person can simply not respond or block e-mail.

But what happens if the partners meet face to face? People often complain that pictures they have been provided of the partner are misleading. And once couples begin to think more seriously about the relationship, the reality of family situations, work demands, goals, timing, values, and money all add new dimensions to the mix.

Singles

The number of adults who remain single has increased dramatically in the last 30 years. We have more people who never marry, more widows and more divorcees driving up the number of singles. Singles represent about 25 percent of American households. Singlehood has become a more acceptable lifestyle than it was in the past and many singles are very happy with their status. Whether or not a single person is happy depends on the circumstances of their remaining single.

Stein’s Typology of Singles

Many of the research findings about singles reveal that they are not all alike. Happiness with one’s status depends on whether the person is single by choice and whether the situation is permanent. Let’s look at Stein’s (1981) four categories of singles for a better understanding of this.

- Voluntary temporary singles: These are younger people who have never been married and divorced people who are postponing marriage and remarriage. They may be more involved in careers or getting an education or just wanting to have fun without making a commitment to any one person. They are not quite ready for that kind of relationship. These people tend to report being very happy with their single status.

- Voluntary permanent singles: These individuals do not want to marry and aren’t intending to marry. This might include cohabiting couples who don’t want to marry, priests, nuns, or others who are not considering marriage. Again, this group is typically single by choice and understandably more contented with this decision.

- Involuntary temporary: These are people who are actively seeking mates. They hope to marry or remarry and may be involved in going on blind dates, seeking a partner on the internet or placing “getting personal” aids in search of a mate. They tend to be more anxious about being single.

- Involuntary permanent: These are older divorced, widowed, or never-married people who wanted to marry but have not found a mate and are coming to accept singlehood as a probable permanent situation. Some are bitter about not having married while others are more accepting of how their life has developed.

We now turn our attention to theories of love.

Types of Love

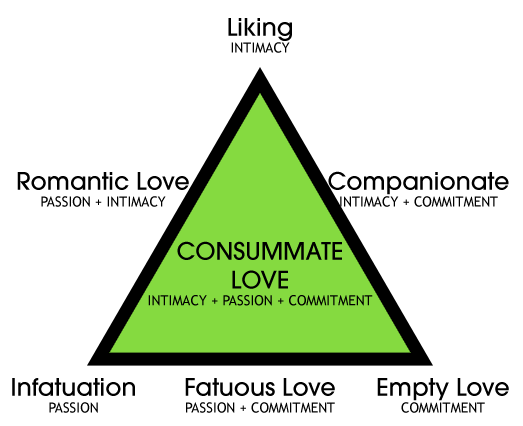

Sternberg’s Triangle of Love: Three Components (Ob11)

Sternberg (1988) suggests that there are three main components of love: passion, intimacy, and commitment, for his triangle of love theory. Love relationships vary depending on the presence or absence of each of these components. Passion refers to the intense, physical attraction partners feel toward one another. Intimacy involves the ability the share feelings, personal thoughts, and psychological closeness with the other. Commitment is the conscious decision to stay together. Passion can be found in the early stages of a relationship, but intimacy takes time to develop because it is based on knowledge of the partner. Once intimacy has been established, partners may resolve to stay in the relationship. Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Let’s look at other possibilities.

Liking: In this relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner ‘thinks of you as a friend’ can be a devastating blow if you are attracted to them and seek a romantic involvement.

Infatuation: Perhaps, this is Sternberg’s version of “love at first sight.” Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one’s head; it may be difficult to eat and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is rather short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on chemical attraction and an image of what one thinks the other is all about.

Fatuous Love: However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction and yet one, or both, is also talking of making a lasting commitment. Sometimes this is out of a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love: This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion (money, childrearing, status). Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship (for the children, because of a religious conviction, or because there are no alternatives perhaps), but do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love: Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness but have not made plans to continue ‘no matter what’. This may be true because they are not in a position to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love: Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one another and they are committed to staying together. But their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out. This may be interpreted as ‘just the way things are’ after so much time together or there may be a sense of regret and loss. Nevertheless, partners are good friends committed to one another.

Consummate Love: Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love. This is often the ideal type of love. The couple shares passion; the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends as well as lovers and they are committed to staying together.

Applications of Sternberg’s Theory

Do these types of love mean anything? Is love necessary or helpful for reproduction in humans?

One study tested this hypothesis using Sternberg’s Triangular Love scale as their operational definition of love. The three components of passion, commitment, and intimacy were measured in a traditional hunter-gatherer tribe in Tanzania, and researchers gathered data about which type of relationship was most correlated with successful reproduction.

Try to predict the results of the study.

You were probably were able to discern that this study examines the correlation between types of relationships and reproductive success, or the number of children a woman has. In psychology, we learn that correlation does NOT equal causation, so just because a person is in a committed relationship, this does not mean they will have children.

So what does correlation really mean? It means there is a relationship between the variables. Remember, that with positive correlation, as one variable increases, so does the other. In a negative correlation, as one variable increases the other decreases.

Types of Lovers (Ob 12)

Lee (1973) offers a theory of love styles or types of lovers derived from an analysis of writings about love through the centuries. As you read these, think about how these styles might become part of the types of love described above.

Pragma is a style of love that emphasizes the practical aspects of love. The pragmatic lover considers compatibility and the sensibility of their choice of partners. This lover will be concerned with goals in life, status, family reputation, attitudes about parenting, career issues and other practical concerns.

Mania is a style of love characterized by volatility, insecurity, and possessiveness. This lover gets highly upset during arguments or breakups, may have trouble sleeping when in love, and feels emotions very intensely.

Agape is an altruistic, selfless love. These partners give of themselves without expecting anything in return. Such a lover places the partner’s happiness above their own and is self-sacrificing to benefit the partner.

Eros is an erotic style of loving in which the person feels consumed. Physical chemistry and emotional involvement are important to this type of lover.

Lupus refers to a style of loving that emphasizes the game of seduction and fun. Such a lover stays away from commitment and often has several love interests at the same time. This lover does not self-disclose and in fact, may prefer to keep the other guessing. This lover can end a relationship easily.

Storage is a style of love that develops slowly over time. It often begins as a friendship and becomes sexual much later. These partners are likely to remain friends even after the breakup.

Frames of Relationships (Ob 13)

Another useful way to consider relationships is to consider the amount of dependency in the relationship. Davidson (1991) suggests three models: A-frame, H-frame, or M-frame.

- The A-frame relationship is one in which the partners lean on one another and are highly dependent on the other for survival. If one partner changes, the other is at risk of ‘falling over’. This type of relationship cannot easily accommodate change and the partners are vulnerable should change occur. A breakup could be devastating.

- The H-frame relationship is one in which the partners live parallel lives. They rarely spend time with one another and tend to have separate lives. What time they do share is usually spent meeting obligations rather than sharing intimacies. This independent type of relationship can end without suffering emotionally.

- The M-frame relationship is interdependent. Partners have a strong sense of connection but also are able to stand alone without suffering devastation. If this relationship ends, partners will be hurt and saddened, but will still be able to stand alone. This ability comes from a strong sense of self-love. Partners can love each other without losing a sense of self. And each individual has self-respect and confidence that enriches the relationship as well as strengthens the self.

We have been looking at love in the context of many kinds of relationships. In our next lesson, we will focus more specifically on marital relationships. But before we do, we examine the dynamics of falling in and out of love.

The Process of Love and Breaking Up (Ob 14)

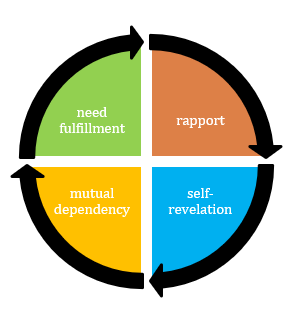

Reiss (1960) provides a theory of love as a process. Reiss’s Wheel Theory of Love was one of the first developmental stage models to conceptualize courtship, relationship development, and mate selection as a circular process that consists of four interrelated parts: rapport, self‐revelation, mutual dependency, and intimacy need fulfillment.

Based on the wheel theory of love, love relationships begin with the establishment of rapport. Rapport involves sharing likes, preferences, establishing some common interests. The next step is to begin to disclose more personal information through self-revelation. When one person begins to open up, the social expectation is that the other will follow and also share more personal information so that each has made some risk and trust is built. Sexual intimacy may also become part of the relationship. Gradually, partners begin to disclose even more about themselves and are met with support and acceptance as they build mutual dependency. With time, partners come to rely on each other for need fulfillment. The wheel must continue in order for love to last. It becomes important for partners to continue to establish rapport by discussing the day’s events, communicating about their goals and desires, and showing signs of trust. Partners must continue to rely on one another to have certain needs fulfilled. If the wheel turns backward, partners talk less and less, rely less on one another and are less likely to disclose.

Process of Disaffection: Breaking Up (Ob 15)

When relationships are new, partners tend to give one another the benefit of the doubt and focus on what they like about one another. Flaws and imperfections do not go unnoticed; rather, they are described as endearing qualities. So, for example, the partner who has a very large nose is described as ‘distinguished’ or as having a ‘striking feature.’ This is very exhilarating because features that someone may have previously felt self-conscious about are now accepted or even appreciated. However, once partners begin the process of breaking up, these views are abandoned and questionable qualities are once again flaws and imperfections. Kerstin (1990) provides a look at the dynamics of breaking up. Although this work is primarily about divorce, the dynamics of dissolving any long-term relationship are similar. The beginning phase of breaking up involves seeing imperfections in the relationship but remaining hopeful that things will improve. This improvement will require the partner’s cooperation because they are primarily at fault. So, as long as the offending partner makes the necessary changes, and of course the offended partner will provide the advice, support, and guidance required, the relationship will continue. (If you are thinking that this is not going to work-you are right. Attempts to change one’s partner are usually doomed to failure. Would you want your partner to try to change you?)

Once it becomes clear that efforts to change are futile, the middle phase is entered. This phase is marked by disappointment. Partners talk less and less, make little eye contact and grow further apart. One may still try to make contact, but the other is clearly disengaged and is considering the benefits and costs of leaving the relationship.

In the end phase, the decision to leave has been made. The specific details are being worked out. Turning a relationship around is very difficult at this point. Trust has diminished, and thoughts have turned elsewhere. This stage is one of hopelessness.

Parenting (Ob 16)

Increasingly, families are postponing or not having children. Families that choose to forego having children are known as childfree families, while families that want but are unable to conceive are referred to as childless families. As more young people pursue their education and careers, age at first marriage has increased; similarly, so has the age at which people become parents. With a college degree, the average age for women to have their first child is 30.3, but without a college degree, the average age is 23.8. Marital status is also related, as the average age for married women to have their first child is 28.8, while the average age for unmarried women is 23.1. Overall, the average age of first time mothers has increased to 26, up from 21 in 1972, and the average age of first time fathers has increased to 31, up from 27 in 1972 in the United States (Bui & Miller, 2018). The age of first-time parents in the U.S. increased sharply in the 1970s after abortion was legalized. Since the age of first-time parents varies by geographic region in the U.S. and women’s rights to abortion are being challenged in some states, it will be interesting to follow the norms and trends for first-time parents in the future. Despite the fact that young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in life (Wang & Taylor, 2011).

The decision to become a parent should not be taken lightly. There are positives and negatives associated with parenting that should be considered. Many parents report that having children increases their well-being (White & Dolan, 2009). Researchers have also found that parents, compared to their non-parent peers, are more positive about their lives (Nelson et al., 2013). On the other hand, researchers have also found that parents, compared to non-parents, are more likely to be depressed, report lower levels of marital quality, and feel like their relationship with their partner is more businesslike than intimate (Walker, 2011).

If you do become a parent, your parenting style will impact your child’s future success in romantic and parenting relationships. Recall from chapter 5 (early childhood) that there are several different parenting styles. Authoritative parenting, arguably the best parenting style, is both demanding and supportive of the child (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Support refers to the amount of affection, acceptance, and warmth a parent provides. Demandingness refers to the degree a parent controls their child’s behavior. Children who have authoritative parents are generally happy, capable, and successful (Maccoby, 1992).

Support for the benefits of authoritative parenting has been found in countries as diverse as the Czech Republic (Dmitrieva et al., 2004), India (Carson et al. 1999), China (Pilgrim et al., 1999), Israel (Mayseless et al., 2003), and Palestine (Punamaki et al., 1997). In fact, authoritative parenting appears to be superior in Western, individualistic societies—so much so that some people have argued that there is no longer a need to study it (Steinberg, 2001). Other researchers are less certain about the superiority of authoritative parenting and point to differences in cultural values and beliefs. For example, while many European-American children do poorly with too much strictness (authoritarian parenting), Chinese children often do well, especially academically. The reason for this likely stems from Chinese culture viewing strictness in parenting as related to training, which is not central to American parenting (Chao, 1994).

The Development of Parents

Think back to an emotional event you experienced as a child. How did your parents react to you? Did your parents get frustrated or criticize you, or did they act patiently and provide support and guidance? Did your parents provide lots of rules for you or let you make decisions on your own? Why do you think your parents behaved the way they did?

Think back to an emotional event you experienced as a child. How did your parents react to you? Did your parents get frustrated or criticize you, or did they act patiently and provide support and guidance? Did your parents provide lots of rules for you or let you make decisions on your own? Why do you think your parents behaved the way they did?

Psychologists have attempted to answer these questions about the influences on parents and understand why parents behave the way they do. Because parents are critical to a child’s development, a great deal of research has been focused on the impact that parents have on children. Less is known, however, about the development of parents themselves and the impact of children on parents. Nonetheless, parenting is a major role in an adult’s life. Parenthood is often considered a normative developmental task of adulthood. Cross-cultural studies show that adolescents around the world plan to have children. In fact, most men and women in the United States will become parents by the age of 40 years (Martinez et al., 2012).

People have children for many reasons, including emotional reasons (e.g., the emotional bond with children and the gratification the parent–child relationship brings), economic and utilitarian reasons (e.g., children provide help in the family and support in old age), and social-normative reasons (e.g., adults are expected to have children; children provide status) (Nauck, 2007).

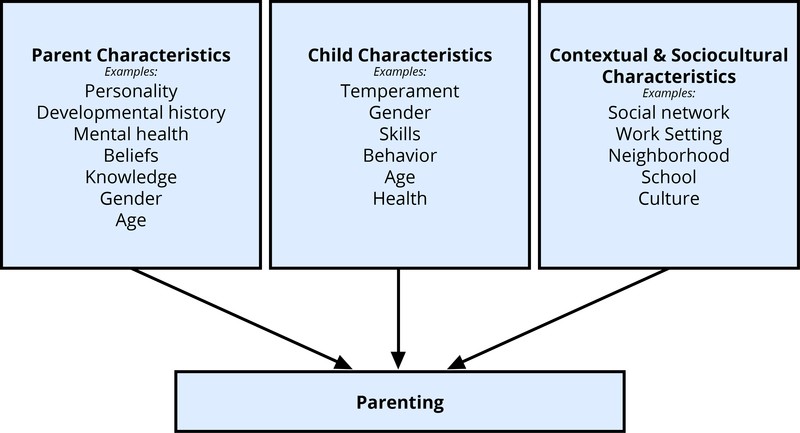

Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parental behavior include 1) parent characteristics, 2) child characteristics, and 3) contextual and sociocultural characteristics (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the age of the parent, gender, beliefs, personality, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie et al., 2009). Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children.

Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff et al., 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde et al., 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children. Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn (Grusec et al., 1996). Parents also talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotion words with their daughters (Crowley et al., 2001).

The parent–child relationship does not occur in isolation. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger & Conger, 2002). Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). For example, parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, and goals involving maintaining harmonious relationships and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. These differences in parental goals are influenced by culture and by immigration status. Other important contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings don’t always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011). Many contextual factors influence parenting.

Career Development and Employment (Ob 16)

Work plays a significant role in the lives of people, and emerging and early adulthood is the time when most of us make choices that will establish our careers. Career development has a number of stages defined by Super (1980):

Stage One: As children, we may select careers based on what appears glamorous or exciting to us (Patton & McMahon, 1999). There is little regard in this stage for whether we are suited for our occupational choices.

Stage Two: In the second stage, teens include their abilities and limitations, in addition to the glamour of the occupation when narrowing their choices.

Stage Three: Older teens and emerging adults narrow their choices further and begin to weigh more objectively the requirements, rewards, and downsides to careers, along with comparing possible careers with their own interests, values, and future goals (Patton & McMahon, 1999). However, some young people in this stage fall into careers simply because these were what was available at the time, because of family pressures to pursue particular paths, or because these were high paying jobs, rather than from an intrinsic interest in that career path (Patton & McMahon, 1999).

Stage Four: Super (1980) suggests that by our mid to late thirties, many adults settle in their careers. Even though they might change companies or move up in their position, there is a sense of continuity and forward motion in their career. However, some people at this point in their working life may feel trapped, especially if there is little opportunity for advancement in a more dead-end job.

How have things changed for Millennials compared with previous generations of early adults? In recent years, young adults are more likely to find themselves job-hopping, and periodically returning to school for further education and retraining than in prior generations. However, researchers find that occupational interests remain fairly stable. Thus, despite the more frequent change in jobs, most people are generally seeking jobs with similar interests rather than entirely new careers (Rottinghaus et al., 2007). Recent research also suggests that Millennials are looking for something different in their place of employment. According to a recent Gallup poll report (2016), Millennials want more than a paycheck, they want a purpose.

Unfortunately, only 29% of Millennials surveyed by Gallup reported that they were “engaged” at work. In fact, they report being less engaged than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers; with 55% of Millennials saying they are not engaged at all with their job. This indifference to their workplace may explain the greater tendency to switch jobs. With their current job giving them little reason to stay, they are more likely to take any new opportunity to move on. Only half of Millennials saw themselves working at the same company a year later. Gallup estimates that this employment turnover and lack of engagement costs businesses $30.5 billion a year.

Working adults spend a large part of their waking hours in relationships with coworkers and supervisors. People are spending as much, or more, time at work than they are with their family and friends (Kaufman & Hotchkiss, 2003). Riordan and Griffeth (1995) found that people who worked in an environment where friendships could develop and be maintained were more likely to report higher levels of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment, and they were less likely to leave that job. Similarly, a Gallup poll revealed that employees who had close friends at work were almost 50% more satisfied with their jobs than those who did not (Armour, 2007). Elsesser and Peplau (2006) found that many workers reported that friendships grew out of collaborative work projects, and these friendships made their days more pleasant. Because these relationships are forced upon us by work, researchers focus less on their presence or absence and instead focus on their quality. High quality work relationships can make jobs enjoyable and less stressful. This is because workers experience mutual trust and support in the workplace to overcome work challenges. Liking the people we work with can also translate to more humor and fun on the job. Research has shown that supervisors who are more supportive have employees who are more likely to thrive at work (Paterson et al., 2014; Monnot & Beehr, 2014; Winkler et al. 2015). On the other hand, poor quality work relationships can make a job feel like drudgery. Everyone knows that horrible bosses can make the workday unpleasant. Supervisors that are sources of stress have a negative impact on the subjective well-being of their employees (Monnot & Beehr, 2014). Specifically, research has shown that employees who rate their supervisors high on the so-called “dark triad”—psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism—reported greater psychological distress at work, as well as less job satisfaction (Mathieu et al, 2014). In addition to the direct benefits or costs of work relationships on our well-being, we should also consider how these relationships can impact our job performance. Research has shown that feeling engaged in our work and having a high job performance predicts better health and greater life satisfaction (Shimazu et al.,2015). Given that so many of our waking hours are spent on the job—about 90,000 hours across a lifetime—it makes sense that we should seek out and invest in positive relationships at work.

What role does gender play in career and employment? Gender also has an impact on career choices. Despite the rise in the number of women who work outside of the home, there are some career fields that are still pursued more by men than women. Jobs held by women still tend to cluster in the service sector, such as education, nursing, and child-care worker. While in more technical and scientific careers, women are greatly outnumbered by men. Jobs that have been traditionally held by women tend to have lower status, pay, benefits, and job security (Ceci & Williams, 2007). In recent years, women have made inroads into fields once dominated by males, and today women are almost as likely as men to become medical doctors or lawyers. Despite these changes, women are more likely to have lower-status, and thus less pay than men in these professions. For instance, women are more likely to be a family practice doctor than a surgeon or are less likely to make partner in a law firm (Ceci & Williams, 2007).

Unfortunately sexism can happen in the workplace. In the United States, women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions, such as engineering, aviation, and construction (Blau et al., 2010; Ceci & Williams, 2011). Occupational sexism involves discriminatory practices, statements, or actions, based on a person’s sex, that occur in the workplace. This can also include a sexist bias for expectations of workers based on their gender. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing; when a woman behaves in an unfriendly or assertive manner, she may be disliked or perceived as aggressive because she has violated a gender role (Rudman, 1998). In contrast, a man behaving in a similarly unfriendly or assertive way might be perceived as strong or even gain respect in some circumstances. Another form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination. In 2008, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that while female employment rates have expanded, and gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed nearly everywhere, on average women still have a 20 percent less chance to have a job. Despite the fact that many countries, including the U.S., have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce (Council of Economic Advisors, 2015). US Census Bureau data from 2020 still shows that women of all races earned, on average, just 83 cents for every $1 earned by men of all races. For reference, in 1960, when women’s pay was 61% of men’s in the US. In 2021, in the United States, women account for 47% of the overall labor force, yet they make only 40.9% of managers in 2021 (US Census Bureau, 2022).

Conclusion

Early adulthood is a dynamic stage of life filled with exploration, growth, and the pursuit of significant milestones. It is a time when individuals typically reach their peak physical condition, yet also begin to experience the subtle signs of aging. Cognitively, early adults develop a more nuanced and complex way of thinking, allowing them to navigate the challenges and complexities of adult life with greater flexibility and practicality. This stage is often marked by a focus on establishing intimate relationships and building a solid foundation for future careers. While many individuals follow traditional paths such as marriage and parenthood, it is important to recognize the diverse range of choices and experiences that characterize early adulthood today.

Whether pursuing higher education, embarking on a career, forming committed relationships, or starting a family, early adults are actively shaping their identities and laying the groundwork for their future selves. This period is filled with both exciting possibilities and daunting challenges, as individuals navigate the complexities of love, work, and personal growth. As you embark on your own journey through early adulthood, remember to embrace the opportunities for self-discovery and personal fulfillment, while also remaining adaptable and resilient in the face of life’s inevitable changes and uncertainties.

Chapter Review Practice Quiz

Chapter 9 Key terms

| A-frame |

middle phase (break up)

|

|

authoritative parenting

|

mutual dependency

|

|

beginning phase (break up)

|

occupational sexism

|

| cohabitation |

physiological peak

|

|

dating cohabitation

|

premarital cohabitation

|

|

dialectical thought

|

principle of least interest

|

|

ending phase (break up)

|

propinquity |

| endogamy | rapport |

| exogamy | self-revelation |

|

filter theory of mate selection

|

social exchange theory

|

|

gamete intra-fallopian tube transfer (GIFT)

|

substance abuse

|

| H-frame |

substitute marriage

|

|

In vitro fertilization (IVF)

|

trial marriage |

| infertility |

triangle love theory (Sternberg)

|

|

intimacy vs isolation (Erikson)

|

wheel of love theory

|

| M-frame |

Zygote intra-fallopian tube transfer (ZIFT)

|

| monogamy |

Media Attributions

- 1024px-Génération_Z is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_03 © Vic is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_01 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Private: Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_02 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_04 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_05 © WordRidden is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_06 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_03 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_04 © Sklum is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Private: Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_05 © Pixabay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_06 is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Private: Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_07 © Flickr is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Chapter_9_Early_Adulthood_Include_V3_08 © Lumen is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Desk Filled with Computers and Office Supplies © Andrew Taylor is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

early - mid 20s is “prime of your life” as your reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity are operating at their best.

excessive use of a drug (such as alcohol, narcotics, or cocaine): use of a drug without medical justification

not fertile or productive, incapable of or unsuccessful in achieving pregnancy

procedure involves removing eggs from the female and fertilizing the eggs outside the woman’s body

implanting both sperm and ova into the fallopian tube and fertilization is allowed to occur naturally

sperm and ova are fertilized outside of the woman’s body and the fertilized egg or zygote is then implanted in the fallopian tube

ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions

Erikson stage, early adulthood is finding intimacy - honestly, closeness, love - during this timeframe or ending stage in isolation

involves living together in a sexually intimate relationship without being married

people testing the relationship before marriage by living together

These partnerships are entered into for fun or convenience and involve less commitment than premarital cohabitation

type of cohabitation in which partners are trying to see what it might be like to be married

partners are committed to one another and are not necessarily seeking marriage

people apply economic principles when evaluating relationships, either consciously or unconsciously, conducting cost-benefit analysis while also comparing alternatives

the partner who has the most to lose without the relationship (or is the most dependent on the relationship) will have the least amount of power and is in danger of being exploited

marriage within a specific group as required by custom or law

the mating of like with like

the pool of eligible partners becomes narrower as it passes through filters used to eliminate members of the pool

nearness in place or time

types of love based around passion, commitment, intimacy, has a triangle that shared different types of love with all 3 making up consummate love

is one in which the partners lean on one another and are highly dependent on the other for survival

is one in which the partners live parallel lives

the relationship is interdependent

love relationships begin with the establishment of rapport

a friendly, harmonious relationship

the revelation of one’s own thoughts, feelings, and attitudes especially without deliberate intent

partners begin to disclose even more about themselves and are met with support and acceptance

‘of breaking up’ involves seeing imperfections in the relationship but remaining hopeful that things will improve

‘of breaking up’ once it becomes clear that efforts to change are futile; marked by disappointment

‘of breaking up’ the decision to leave has been made

Parenting Style: children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high, but reasonable expectations for children’s behavior, communicate well with them, are warm, loving and responsive, and use reasoning, rather than coercion as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior

discriminatory practices, statements, or actions, based on a person’s sex, that occur in the workplace. This can also include a sexist bias for expectations of workers based on their gender