Chapter 12: Death and Dying

Objectives:

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- Compare the leading causes of death in the United States with those of developing countries.

- Compare physiological, social, and psychic death.

- List and describe the stages of loss based on various models including that of Kubler-Ross.

- Explain the philosophy and practice of palliative care.

- Describe hospice care.

- Differentiate attitudes toward hospice care based on race and ethnicity.

- Compare euthanasia, passive-euthanasia, and physician-assisted suicide.

- Characterize bereavement and grief.

- Express your own ideas about death and dying.

The objectives are indicated in the reading sections below.

Introduction

We have now reached the end of the lifespan. While it is true that death occurs more commonly at the later stages of age, death can occur at any point in the life cycle. Death is a deeply personal experience evoking many different reactions, emotions, and perceptions.

“Everything has to die,” he told her during a telephone conversation. “I want you to know how much I have enjoyed being with you, having you as my friend, and confident and what a good father you have been to me. Thank you so much.” she told him. “You are entirely welcome.” he replied. He had known for years that smoking will eventually kill him. But he never expected that lung cancer would take his life so quickly or be so painful. A diagnosis in late summer was followed with radiation and chemotherapy during which time there were moments of hope interspersed with discussions about where his wife might want to live after his death and whether or not he would have a blood count adequate to let him proceed with his next treatment. Hope and despair exist side by side. After a few months, depression and quiet sadness preoccupied him although he was always willing to relieve others by reporting that he ‘felt a little better’ if they asked. He returned home in January after one of his many hospital stays and soon grew worse. Back in the hospital, he was told of possible treatment options to delay his death. He asked his family members what they wanted him to do and then announced that he wanted to go home. He was ready to die. He returned home. Sitting in his favorite chair and being fed his favorite food gave way to lying in the hospital bed in his room and rejecting all food. Eyes closed and no longer talking, he surprised everyone by joining in and singing “Happy birthday” to his wife, son, and daughter-in-law who all had birthdays close together. A pearl necklace he had purchased 2 months earlier in case he died before his wife’s birthday was retrieved and she told him how proud she would be as she wore it. He kissed her once and then again as she said goodbye. He died a few days later (Overstreet).

Except for a handful of illnesses in which death does often quickly follow diagnosis, or in the case of accidents or trauma, most deaths come after a lengthy period of chronic illness or frailty (Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2015). A dying process that allows an individual to make choices about treatment, to say goodbyes and to take care of final arrangements is what many people hope for. Such a death might be considered a “good death.” But of course, many deaths do not occur in this way. While modern medicine and better living conditions have led to a rise in life expectancy around the world, death will still be the inevitable final chapter of our lives.

Not all deaths include such a dialogue with family members or being able to die in familiar surroundings. People die suddenly and alone. People leave home and never return. Children precede parents in death; wives precede husbands, and the homeless are bereaved by strangers. In this chapter, we look at death and dying, grief and bereavement. We explore palliative care and hospice. And we explore funeral rites and the right to die.

Defining Death

Death is a physical event in which our bodies stop working, including the absence of breathing and a heartbeat. However, even this statement on describing death is overly simplistic. Our body is far more complex than this, composed of an intricate set of systems working together. These systems don’t all play an equal role in keeping us alive, but if something happens to one of them, it’s likely to affect the functioning of other systems and our body overall. For example, if our heart, lungs, and/or brain lose function, the other organs in our body may also start to fail. However, due to current medical science and advances, the failure of one organ does not guarantee that other systems of the body will inevitably and immediately lose functioning.

Medical professionals sometimes distinguish between clinical death, in which vital organs have stopped working but could be resuscitated, and biological death, in which these organs can’t be resuscitated (Parish et al., 2018). Depending on what caused the death, clinical death may occur before biological death. In cardiac arrest, for example, it may be possible to start the heart beating again. Or biological death may occur on its own: If a person is stabbed in the heart, the heart may sustain too much damage to be repaired. Brain death is the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, meaning the person will never regain consciousness or breathe without artificial support and is legally considered dead (in the US). This standard, established by the Uniform Determination of Death Act (1981), is used to ensure consistent legal and medical practices regarding the definition of death in the United States.

Cultural Groups View of Brain Death

Not all cultures are equally accepting of brain death. In countries such as Japan, China, and the Republic of Korea, brain death is an acceptable diagnosis only in cases of organ donation and requires approval from the patient’s family, but not necessarily an advance directive from the patients themselves. In the Republic of Korea, a diagnosis of brain death also requires unanimous approval from a special committee (Terunuma & Mathis, 2021; Yang & Miller, 2015), making the process longer and more complicated.

We can also look at religious factors in acceptance of brain death. Buddhism views the body and soul holistically, as one entity, with body heat and a heartbeat being signs of life (Terunuma & Mathis, 2021; Yang & Miller, 2015). Because Buddhism has a strong belief in an afterlife and reincarnation, the body must be left intact; harvesting organs for donation is often seen as mutilation (Yang & Miller, 2015). This may explain why organ donation isn’t common in countries with a large Buddhist population, such as China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea (Terunuma & Mathis, 2021).

But death isn’t just a physical event. It has psychological aspects, such as the way people cope with death, prepare and make decisions about end-of-life care, and express grief. Social aspects of death include the way dying people are treated and the cultural factors like religious and spiritual values and beliefs that affect people’s perceptions of dying and choices related to it. A researcher who studies the biological, psychological, and social aspects of death is called a thanatologist.

Aspects of Death (Ob 2)

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physical death, psychological death, and social death. These deaths do not occur simultaneously. Rather, a person’s physiological, social, and psychic death can occur at different times (Pattison, 1977).

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function. The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows and the digestive tract loses moisture and chewing, swallowing, and elimination becomes painful processes. Circulation slows and mottling or the pooling of blood may be noticeable on the underside of the body appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallower and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus filled passageways. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less although continues to hear. The kinds of symptoms noted prior to death in patients under hospice care (care focused on helping patients die as comfortably as possible) are noted below. When a person no longer has brain activity, they are clinically dead. Physiological death may take 72 or fewer hours.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death. Social death occurs when others begin to withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. A patient who is dying may be referred to as “circling the drain” meaning that they are approaching death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life and those who experience social death are deprived of the benefits that come from loving interaction with others.

Being aware (or not) of impending death might affect a person’s self-concept, and how helpful that awareness is can vary person to person. Psychic death occurs when the dying person begins to accept death and to withdraw from others and regress into the self. This can take place long before physiological death (or even social death if others are still supporting and visiting the dying person) and can even bring physiological death closer. People have some control over the timing of their death and can hold on until after important occasions or die quickly after having lost someone important to them. They can give up their will to live.

Dying Trajectories

There are 4 dying trajectories based on the nature and rate of decline.

- Sudden death is an abrupt loss of function, as in heart attack, stroke, and accidents.

- Terminal illness is a more gradual loss of function, such as from cancer.

- Organ failure is characterized by an overall gradual decline with fluctuating cycles of illness and improvement, as in kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and congestive heart failure.

- Frailty is also gradual, but with a lower level of functioning and steadier decline without cycles of improvement, as in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes.

Death Process for Terminally Ill: For those individuals who are terminal and death is expected, a series of physical changes occur. Individual experiences may be influenced by such variables as the cause of death, the person’s general health, medications and other significant factors. All dying experiences are unique and influenced by many factors, such as the particular illness and the types of medications being taken, but there are some physical changes that are fairly common.

Bell (2010) identifies some of the major changes that occur in the weeks, days, and hours leading up to death:

Weeks Before Passing for death process

o Minimal appetite; prefer easily digested foods

o Increase in the need for sleep

o Increased weakness

o Incontinence of bladder and/or bowel

o Restlessness or disorientation

o Increased need for assistance with care

Days Before Passing for death process

o Decreased level of consciousness

o Pauses in breathing

o Decreased blood pressure

o Decreased urine volume and urine color darkens

o Murmuring to people others cannot see

o Reaching in air or picking at covers

o Need for assistance with all care

Days to Hours Before Passing for death process

o Decreased level of consciousness or comatose-like state

o Inability to swallow

o Pauses in breathing become longer

o Shallow breaths

o Weak or absent pulse

o Knees, feet, and/or hands becoming cool or cold

o Knees, feet, and/or hand discoloring to a purplish hue

o Noisy breathing due to relaxed throat muscles often called a “death rattle”

o Skin coloring becoming pale, waxen (pp. 5, 176-177)

Most Common Causes of Death (Ob1)

Like life expectancy, the most common causes of death differ by demographic variables. For example, men worldwide are more likely to die of accidents, murder, and suicide than women (WHO, 2019). Geographic location also plays a role, usually due to the resources and living conditions in an area. For example, in Angola, diarrheal disease (cholera, rotavirus) is the most common cause of death, likely due to lack of clean drinking water; however, in Canada, the leading cause of death is heart disease (Global Health Observatory, n.d.-a).

As of 2019, heart disease was the most common cause of death worldwide. It accounted for 9 million deaths recorded that year; stroke and COPD were second and third (WHO, 2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic changed the statistics somewhat. The WHO estimates that the excess mortality attributable to COVID-19 was 3 million people in 2020. In other words, in 2020, COVID-19 caused 3 million more deaths worldwide than would have occurred without it (WHO, 2021). In the United States, COVID-19 replaced unintentional injury/accidents as the third most common cause of death in 2020 and 2021 (Xu et al., 2022), then dropped to fourth in 2022 (Ahmad et al., 2023).

Falls are another frequent cause of injury-related death among adults ages sixty-five and older, and the death rate from falls is increasing (CDC, 2024). The age-adjusted fall death rate increased by 41 percent from 2012 to 2021, from approximately 55 to nearly 80 fall-related deaths per 100,000 older adults (CDC, 2024).

Common causes of death also vary by age. In the United States, the most common cause of death for infants less than one year old is congenital abnormality (WISQARS, 2022). From ages 1 to 44, the most common cause is unintentional injury/accident. Even within that category, however, there are age-related differences. For children aged 1 to 4, the most common type of fatal unintentional injury is drowning, while from 5 to 24, it is motor vehicle accidents (CDC, n.d.). In many developing nations, infectious diseases and malnutrition are more commonly the causes of death, especially in children under five (Abubakari et al., 2019; Djoumessi, 2022; GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators, 2020).

Table. Top 3 Causes of Death in U.S. in 1900s and 1990s

| Top 3 leading causes of death in the United States | |

| 1900’s | 1990’s |

| Pneumonia & Influenza | Heart Disease |

| Tuberculosis | Cancer |

| Diarrhea & Enteritis | Stroke |

| 30% of all deaths | 60% of all deaths. |

In the US in 2021, the top leading cause was heart disease, followed by cancer (CDC, 2021). COVID-19, newly added as a cause of death in 2020, became the 3rd leading cause of death. Unintentional injuries became the 4th leading cause in 2021 followed by stroke. Chronic lower respiratory diseases is the 6th, and Alzheimer disease is the 7th. Diabetes became the 8th, followed by pneumonia. Then, kidney disease became the 10th leading cause in 2020. The 10 leading causes accounted for 74.1% of all deaths in the United States in 2020.

These were the top causes of death for various age groups in the United States in the year 2021 (CDC):

Table. Top Causes of Death by Age Group in the U.S. in 2021

|

Age range |

Top cause of death |

|

< 1 year |

Congenital anomalies (short gestation #2) |

|

1 – 4 years |

Unintentional Injury (congenital anomalies #2) |

|

5 – 9 years |

Unintentional Injury (Malignant Neoplasms (cancer) #2) |

|

10 – 14 years |

Unintentional Injury (suicide #2) |

|

15 – 24 years |

Unintentional Injury (homicide #2) |

|

25 – 34 years |

Unintentional Injury (suicide #2) |

|

35 – 44 years |

Unintentional Injury (COVID-19 #2) |

|

45 – 54 years |

COVID-19 (heart disease #2) |

|

55 – 64 years |

Malignant Neoplasms (cancer) (heart disease #2) |

|

65 + |

Heart Disease (Malignant Neoplasms (cancer) #2) |

How might cause of death the way we think of death, how we grieve, and the amount of control a person has over his or her own dying process?

Table. Leading causes of deaths for persons 65 years of age and older (Note: pre-covid; CDC, 2001)

|

|

American Asian |

White |

Black |

Pacific Islander |

Hispanic |

|

1 |

Heart Disease |

Heart Disease |

Heart Disease |

Heart Disease |

Heart Disease |

|

2 |

Cancer |

Cancer |

Cancer |

Cancer |

Cancer |

|

3 |

Stroke |

Stroke |

Diabetes |

Stroke |

Stroke |

|

4 |

COPD |

Diabetes |

Stroke |

Pneu/Influenza |

COPD |

|

5 |

Pneu/Influenza |

Pneu/Influenza |

COPD |

COPD |

Pneu/Influenza |

Deadliest Diseases Worldwide

In 2021, the top 10 causes of death accounted for 39 million deaths, or 57% of the total 68 million deaths worldwide (WHO, 2024). The top global causes of death, in order of total number of lives lost, are associated with two broad topics: cardiovascular (ischemic heart disease, stroke) and respiratory (COVID-19, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections), with COVID-19 emerging as the second leading causes of death globally. Causes of death can be grouped into three categories: communicable (infectious and parasitic diseases and maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions), noncommunicable (chronic) and injuries. At a global level, 7 of the 10 leading causes of deaths in 2021 were noncommunicable diseases, accounting for 38% of all deaths, or 68% of the top 10 causes.

- Heart disease

- COVID-19

- Stroke

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Lower respiratory infections

- Trachea, Bronchus, and lung cancers

- Alzheimer’s and other dementias

- Diabetes mellitus

- Kidney Diseases

- Tuberculosis

Developmental Perceptions of Death

The concept of death changes as we develop from early childhood to late adulthood. Cognitive development, societal beliefs, familial responsibilities, and personal experiences all shape an individual’s view of death (Batts, 2004; Erber & Szuchman, 2015; National Cancer Institute, 2013).

Infancy: Certainly, infants do not comprehend death, however, they do react to the separation caused by death. Infants separated from their mothers may become sluggish and quiet, no longer smile or coo, sleepless, and develop physical symptoms such as weight loss.

Early Childhood: As you recall from Piaget’s preoperational stage of cognitive development, young children experience difficulty distinguishing reality from fantasy. It is therefore not surprising that young children lack an understanding of death. They do not see death as permanent, assume it is temporary or reversible, think the person is sleeping, and believe they can wish the person back to life. Additionally, they feel they may have caused death through their actions, such as misbehavior, words, and feelings.

Middle Childhood: Although children in middle childhood begin to understand the finality of death, up until the age of 9 they may still participate in magical thinking and believe that through their thoughts they can bring someone back to life. They also may think that they could have prevented the death in some way, and consequently feel guilty and responsible for the death.

Late Childhood: At this stage, children understand the finality of death and know that everyone will die, including themselves. However, they may also think people die because of some wrongdoing on the part of the deceased. They may develop fears of their parents dying and continue to feel guilty if a loved one dies.

Adolescence: Adolescents understand death as well as adults. With formal operational thinking, adolescents can now think abstractly about death, philosophize about it, and ponder their own lack of existence. Some adolescents become fascinated with death and reflect on their own funeral by fantasizing on how others will feel and react. Despite a preoccupation with thoughts of death, the personal fable of adolescence causes them to feel immune to death. Consequently, they often engage in risky behaviors, such as substance use, unsafe sexual behavior, and reckless driving, thinking they are invincible.

Talking with children about death and grief can be challenging. Here are some resources for adults to use, both with children and for themselves.

- “Sesame Workshop”: This website provides resources and videos on how to talk to children about the loss of a loved one.

- National Public Radio: NPR’s “Life Kit” series discusses how to have difficult conversations with your child.

- UNICEF: UNICEF Parenting offers advice and tips on how to talk to children and teenagers about death.

- The Cove Center for Grieving Children: Read these FAQs about grieving children for more information on what to expect from a grieving child.

Early Adulthood: In adulthood, there are differences in the level of fear and anxiety concerning death experienced by those in different age groups. For those in early adulthood, their overall lower rate of death is a significant factor in their lower rates of death anxiety. Individuals in early adulthood typically expect a long life ahead of them, and consequently do not think about, nor worry about death.

Middle Adulthood: Those in middle adulthood report more fear of death than those in either early or late adulthood. The caretaking responsibilities for those in middle adulthood is a significant factor in their fears. As mentioned previously, middle adults often aid with both their children and parents and they feel anxiety about leaving them to care for themselves.

Late Adulthood: Contrary to the belief that because they are so close to death, they must fear death, those in late adulthood have lower fears of death than other adults. Why would this occur? First, older adults have fewer caregiving responsibilities and are not worried about leaving family members on their own. They also have had more time to complete activities they had planned in their lives, and they realize that the future will not provide as many opportunities for them. Additionally, they have less anxiety because they have already experienced the death of loved ones and have become accustomed to the likelihood of death. It is not death itself that concerns those in late adulthood; rather, it is having control over how they die.

Psychological Aspects of Death

Death also has psychological aspects. The experience of death isn’t the same for everyone. Even when two people share the same cause of death, such as breast cancer, they may differ in the speed of progression, the pain they experience, and the kind and amount of support they have.

Being aware (or not) of impending death might affect a person’s self-concept, and how helpful that awareness is can vary person to person.

Being diagnosed with a terminal illness is likely to change a person’s self-perception (Aho, 2016; Greenberg et al., 1986; Kalish, 1968; Raju & Reddy, 2018; Zhang et al., 2023). When people are unable to care for themselves or participate in typical aspects of daily life, they may experience a loss of identity (Bryden, 2019; Fang et al., 2023; Gaignard & Hurst, 2019). This may also happen when people with dementia forget important memories or loved ones and lose a general sense of continuity in their lives (Blandin, 2016). In her 2019 account of living with dementia, biochemist Christine Bryden–diagnosed with early onset dementia at age forty-six—explained that her intellectual functioning was a key part of her identity and crucial to her career. She worried that her progressing illness was removing that aspect of herself, and that she would become her diagnosis, lose her individuality, and be seen as merely a dementia patient. A study of terminally ill brain cancer patients in India found such results: patients reported that others started to treat them as a sick person and not as an individual, whereas they wanted to be treated as they had been before getting sick (Raju & Reddy, 2018)

Death can be a difficult or awkward topic to discuss or even acknowledge. Psychologist Suzanne M. Miller (1995) proposed two relevant coping styles: monitoring, in which people seek out information about a problem even if it represents bad news, and blunting, in which people avoid potentially distressing information. These styles have implications for how much distress a person may feel when diagnosed with a terminal illness, and they may also influence how comfortable the person is discussing it with others (Pao & Mahoney, 2018).

But do people benefit from knowing they’re dying? Does this knowledge make them scared or prepared? Does it cause them to seek comfort or push others away? These questions don’t have simple answers. In general, thinking about death makes people anxious; however, this anxiety will prompt some people to prepare, while others will feel helpless and overwhelmed. Thinking about their own death also affects the way people interact with others, particularly people they view as different. When people feel that their sense of self is threatened, as when they’re worried about their own death, they try to preserve that sense of self by becoming more committed to cultural values and showing more outgroup bias, negative feelings about people perceived as different (Greenberg et al., 1986; Juhl & Routledge, 2016; Ma-Kellams & Blascovich, 2011; Rubin, 2018). The idea that people try to preserve their identity in the face of a threat of impending death is called terror management theory (Greenberg et al., 1986). However, not everyone reacts to this threat the same way. European-Americans are more likely to react with outgroup bias than are Asian Americans. The collectivist orientation of many Asian cultures may emphasize bonding with others during times of trouble (Ma-Kellams & Blascovich, 2011; Kwon & Park, 2022), although not all research supports this (e.g., Otsubo & Yamaguchi, 2023).

People who worry about what awaits them after death may also experience death anxiety. Nichols and colleagues’ (2018) cross-cultural study looked at the relationship between views of the self and fear of death among Christians, Hindus, and Tibetan Buddhist monks. Christians generally view the soul (self) as separate from the body, existing continuously throughout life and after death. Hindus similarly view the self’s existence as continuous, but believe it is reincarnated after death. These two perspectives may make people fear death if they’re concerned about what might happen to them in the afterlife. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, on the other hand, takes the perspective that nothing is permanent, including the self; therefore, death isn’t something to fear.

Five Stages of Loss (Ob 3)

Kübler-Ross (1969, 1975) describes five themes of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending death. These are not stages that a person goes through in order or only once; nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity. Indeed, the process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life. Nevertheless, these themes help us to understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically. And by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die.

Denial is often the first reaction to overwhelming, unimaginable news. Denial, or disbelief or shock, protects us by allowing such news to enter slowly and to give us time to come to grips with what is taking place. The person who receives positive test results for life-threatening conditions may question the results, seek second opinions, or may simply feel a sense of disbelief psychologically even though they know that the results are true.

Anger also provides us with protection in that being angry energizes us to fight against something and gives structure to a situation that may be thrusting us into the unknown. It is much easier to be angry than to be sad or in pain or depressed. It helps us to temporarily believe that we have a sense of control over our future and to feel that we have at least expressed our rage about how unfair life can be. Anger can be focused on a person, a health care provider, at God, or at the world in general. And it can be expressed over issues that have nothing to do with our death; consequently, being in this stage of loss is not always obvious.

Bargaining involves trying to think of what could be done to turn the situation around. Living better, devoting yourself to a cause, being a better friend, parent, or spouse, are all agreements one might willingly commit to if doing so would lengthen life. Asking to just live long enough to witness a family event or finish a task are examples of bargaining.

Depression is sadness and sadness is appropriate for such an event. Feeling the full weight of loss, crying, and losing interest in the outside world is an important part of the process of dying. This depression makes others feel very uncomfortable and family members may try to console their loved one. Sometimes hospice care may include the use of antidepressants to reduce depression during this stage.

Acceptance involves learning how to carry on and to incorporate this aspect of the life span into daily existence. Reaching acceptance does not in any way imply that people who are dying are happy about it or content with it. It means that they are facing it and continuing to make arrangements and to say what they wish to say to others. Some terminally ill people find that they live life more fully than ever before after they come to this stage.

There is no “right way” to experience the loss. People move through a variety of stages with different frequency and in various ways. It is important to note that Kübler-Ross’s work may not apply to everyone who is grieving. Her research focused only on those who were terminally ill. Friedman and James (2008) and Telford et al. (2006) expressed concern that mental health professionals, along with the general public, may assume that grief follows a set pattern, which may create more harm than good.

Although there is partial support for Kübler-Ross’s themes, having a framework for processing different emotions associated with grief may be comforting or provide structure in an overwhelming situation (Hall, 2014). Regardless of preconceived notions of what grief looks like, health-care providers and others who interact with grieving people need to be flexible and adapt to the needs of the situation (Corr, 2021; Flugelman, 2021; McCoyd et al., 2021). There are different patterns of grieving that vary across individuals, cultures, and the context in which grief occurs. It may not be possible to always accommodate all these variables, but being aware of them is a good first step (Stroebe et al., 2017).

Palliative Care and Hospice (Ob 4, Ob 6, Ob 7)

When individuals become ill, they need to make choices about the treatment they wish to receive. One’s age, type of illness, and personal beliefs about dying affect the type of treatment chosen (Bell, 2010).

Curative care is designed to overcome and cure disease and illness (Fox, 1997). Its aim is to promote complete recovery, not just to reduce symptoms or pain. An example of curative care would be chemotherapy. While curing illness and disease is an important goal of medicine, it is not its only goal. As a result, some have criticized the curative model as ignoring the other goals of medicine, including preventing illness, restoring functional capacity, relieving suffering, and caring for those who cannot be cured.

Palliative care focuses on providing comfort and relief from physical and emotional pain to patients throughout their illness even while being treated (NIH, 2007). Palliative care can be given to anyone with a chronic condition, regardless of prognosis (Casey, 2019). Palliative care is an interdisciplinary approach to specialized medical and nursing care for people with life-limiting illnesses. Although it is an important part of end-of-life care, it is not limited to that stage. Palliative care is provided by a team of physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and other health professionals who work together with the primary care physician and referred specialists to provide additional support to the patient. It focuses on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, physical stress, and mental stress at any stage of illness, with a goal of improving the quality of life for both the person and their family. Medical staff who specialize in palliative care have training tailored to helping patients and their family members cope with the reality of the impending death and make plans for what will happen after.

Palliative care is part of hospice programs. Hospice involves caring for dying patients by helping them be as free from pain as possible, providing them with assistance to complete wills and other arrangements for their survivors, giving them social support through the psychological stages of loss, and helping family members cope with the dying process, grief, and bereavement. Hospice can be provided in a special facility, in the home, or even sometimes in a hospital setting. A doctor may suggest hospice care if the patient is expected to live for fewer than six months. Most hospice care does not include medical treatment of disease or resuscitation although some programs administer curative care as well. The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Family members, who have agreed to put their loved one on hospice, may become anxious when the patient begins to experience the death. They may believe that feeding or breathing tubes will sustain life and want to change their decision. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

Table. Elements of Hospice

|

According to Shannon (2006), the basic elements of hospice include:

Bereavement counseling for the family up to one year after the patient’s death |

Today, there are more than 6,000 hospice programs and over 1,000 of them are offered through hospitals. In 2022, an estimated 1.72 million people received hospice care (NHPCO, 2024). The majority of patients on hospice are cancer patients and typically do not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. The majority of patients on hospice are cancer patients who typically do not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. The average length of stay is less than 25 days (National Center for Health Statistics, 2022). The median length of stay was 18 days, and one out of three patients were on hospice for less than a week. Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subjected to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care (Weitz, 2007). Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. Patients receive palliative care in hospitals and in their homes. When hospice is administered at home, family members may also be part, and sometimes the biggest part, of the care team. Certainly, being in familiar surroundings is preferable to dying in an unfamiliar place. But about 60 to 70% of people die in hospitals and another 16% die in institutions such as nursing homes (APA Online, 2001). Most hospice programs serve people over 65; few programs are available for terminally ill children (Wolfe et al., in Berger, 2005).

The Hospice Foundation of America notes that not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. African-American families may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Chinese-American families may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member’s body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve (Hospital Foundation of America, 2009).

Family Care

According to the 2023 Caregiving in America report, an estimated 53 million Americans are currently caregivers for someone who is dying or chronically ill. Two-thirds of these caregivers are women. This care takes its toll physically, emotionally, and financially. Family caregivers may face the physical challenges of lifting, dressing, feeding, bathing, and transporting a dying or ill family member. They may worry about whether they are performing all tasks safely and properly, as they receive little training or guidance. Such caregiving tasks may also interfere with their ability to take care of themselves and meet other family and workplace obligations. Financially, families may face high out of pocket expenses (IOM, 2015). , most family caregivers are employed, are providing care by themselves with little professional intervention, and there are high costs in lost productivity. As the prevalence of chronic disease rises, the need for family caregivers is growing. Unfortunately, the number of potential family caregivers is declining as the large baby boomer generation enters into late adulthood (Redfoot et al., 2013).

Table. Characteristics of Family Caregivers in the United States

|

Characteristic |

|

|

No home visits by health care professionals |

69% |

|

Caregivers are also employed |

72% |

|

Caregivers for the elderly |

67% |

|

% of employed workers who have been caregiving for 3+ years |

55% |

Adapted from IOM, 2015

End of Life Decisions

Advanced Directives & Medical Orders

Advanced care planning refers to all documents that pertain to end-of-life care. These include advance directives and medical orders. Advance directives include documents that mention a healthcare agent and living wills. These are initiated by the patient. Advanced directives include a healthcare power of attorney (or medical power of attorney), which appoints a healthcare agent or proxy to make medical decisions on your behalf if you are incapacitated. The term health-care proxy, also called a durable power of attorney for health care, is a document that legally authorizes a person to make health-care decisions for someone else. A specific advanced directive is a living will. Living wills are written or video statements that outline the health care initiate the person wishes under certain circumstances. A living will is a legal document that outlines your preferences for medical treatment if you become incapacitated and are unable to communicate your wishes yourself (e.g., terminal illness, severe injury, or being in a persistent vegetative state).

Advance directives may also include other documents requested by the patient, such as Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders or psychiatric advance directives. The abbreviation “DNR” stands for “do not resuscitate (DNR).” It means that if a person’s heart stops beating or if they stop breathing, they don’t want CPR or other lifesaving measures performed on them. A DNR is similar to a living will but addresses only the issue of resuscitation if the heart stops. An advance directive is a direction from the patient, not a medical order. A related directive, a “do not intubate (DNI)” order, prevents health-care providers from inserting breathing tubes into a patient’s nose or mouth. This may be requested instead of or in addition to a DNR order. Finally, a “do not hospitalize (DNH)” order prohibits admitting an individual to a hospital. It is usually used in long-term care settings like nursing homes and is meant to prevent a person from receiving unwanted aggressive medical care if their chances of recovery are low.

It may seem unnecessary to have both a living will and a health-care proxy. Not having a designated health-care proxy can result in family conflicts about who is authorized to make health-care decisions. A health-care proxy can cover situations not identified in the living will, which applies only to life-sustaining treatment. For example, a person with Alzheimer’s disease who needs surgery for a broken arm may not be able to consent to treatment due to cognitive impairment. Because this situation isn’t life-threatening, it’s not covered by a living will, but a health-care proxy could consent to the surgery. Additionally, even if the person has told others what they want, their wishes may not be followed if they aren’t stated in formal legal documents.

There are also medical orders for end of life decisions. In contrast to advanced directives, medical orders are crafted by a medical professional on behalf of a seriously ill patient. Unlike advanced directives, as these are doctor’s orders, they must be followed by other medical personnel. Medical orders include Physician Orders for Life-sustaining Treatment (POLST), do-not-resuscitate, do not-incubate or do-not-hospitalize. In some instances, medical orders may be limited to the facility in which they were written. Several states have endorsed POLST so that they are applicable across healthcare settings (IOM, 2015).

Table. Summary of End of Life Decisions

| Feature | Living Will | Advance Directive | Medical Orders for End of Life (POLST/MOLST/DNR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Legal document specifying your wishes for end-of-life medical care if you are incapacitated | Broad term for documents guiding future medical care, often includes living will and medical power of attorney | Medical orders written and signed by a healthcare provider based on your current wishes for end-of-life care |

| Scope | End-of-life medical treatment preferences | Any instructions about future medical care and decision-makers | Specific, actionable medical orders for emergency and end-of-life care |

| Appoints Decision-Maker | No | Often yes (if it includes healthcare power of attorney) | No (but reflects patient’s wishes and may be completed with a surrogate) |

| Who Completes It? | Individual | Individual | Individual (or surrogate) with healthcare provider |

| Who Signs? | Individual (may need witness/notary) | Individual (may need witness/notary) | Individual (or surrogate) and healthcare provider |

| When It’s Used | When you are incapacitated and near end-of-life | When you are incapacitated (any serious illness or injury) | Immediately, especially in emergencies, across care settings |

| Legal Status | Legal document (varies by state) | Legal document (varies by state) | Medical order, must be honored by healthcare professionals and EMS |

| Examples | Living will, health care directive | Living will, medical power of attorney, combined directives | POLST, MOLST, DNR, DNI, DNH orders |

| Portability | Yes, but may need to be presented | Yes, but may need to be presented | Highly portable; follows patient across care settings |

| Main Purpose | Expresses treatment wishes for future incapacity | Expresses wishes and/or appoints a decision-maker | Ensures immediate compliance with specific medical wishes in emergencies |

Will

A will is a legal document specifying how to handle a person’s possessions, financial assets, real estate, and/or dependents after death. In some cultures, a will may even cover ideas. For example, some Jewish people make an “ethical will” to pass down their life lessons and values (Reischer & Beverley, 2019). A will may also specify what the person wants done with their body (e.g., burial, cremation, donation to science) and the type of funeral or memorial arrangements they would like. In the United States, anyone considered a legal adult, which is eighteen or older in most states, can make a will (American Bar Association, 2013).

A will names an executor, a person responsible for fulfilling the conditions in the will such as by making charitable donations and giving possessions to heirs. The executor is usually a family member or trusted friend. After a person dies, the executor may need to file the person’s will and a copy of the death certificate with the probate court, which oversees matters such as the distribution of property and the assignment of a legal guardian for any minor children. The court then gives the executor the authority to enact the terms in the will and fulfill other duties, such as selling the deceased person’s house to pay off debts. This is not necessary for all wills, and the rules may be different between states.

Despite the fact that many Americans worry about the financial burden of end-of-life care, “more than one-quarter of all adults, including those aged 75 and older, have given little or no thought to their end-of-life wishes, and even fewer have captured those wishes in writing or through conversation” (IOM, 2015, p. 18). If a person dies without a will, also called dying intestate, no one can access their assets until the probate court decides what should be done with them and who has a legitimate claim to them. (The probate court oversees matters such as the distribution of property and the assignment of a legal guardian for any minor children.) This can take several months and means that family members may be cut off from financial assets such as bank accounts and credit cards if they aren’t already recognized as users on those accounts.

Talking about end-of-life wishes

These links contain information and resources to address a variety of questions related to advance directives, including definitions of terms, forms, and (for U.S. residents) state-specific guidelines.

- Learn more about advance directives on the NIA Advance Care Planning website.

- The AARP website gives state-specific-information on how to create advance directives.

- CaringInfo.org, a program of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, has a detailed website on how to create an advance directive.

Here are some practical suggestions for getting started, both for expressing your wishes and for learning about what your family members might want for themselves.

A natural opener might be, “In my lifespan development class, we’re learning about death, and that got me thinking about some things.” You can move on to, “I just finished reading about living wills, and now I’m wondering if you have a living will or anything like that.” Or, “The textbook encouraged us to talk with our families about end-of-life issues; would you be willing to have that conversation with me?”

If someone you know or a recent news story dealt with end-of-life issues, you can say, “I was thinking about what happened to ______ after they were in that accident and their family had to decide whether to keep them on life support,” or “Things are still a big mess in ______’s family because ________ didn’t have a will and now they have to wait for probate court to decide how to divide up the estate.” Examples about other people might create openings in conversations that are more comfortable than asking the person directly about their own wishes and plans.

Once you’re able to have a conversation, be sure to include both practical concerns (types of medical treatment, who makes decisions) and more philosophical concerns (what’s important in life, how much pain or discomfort is tolerable). Be sure to include your own views and wishes as well as asking your loved ones about theirs. You don’t need to discuss everything at once. Most people need time to think and decide about these things.

Talking about end-of-life wishes isn’t a one-time conversation. People’s desires or circumstances may change, and legal documents like health-care proxy forms typically require several conversations and legal consultation. You can express your own concerns, too: “I’m worried I won’t know what to do if something happens to you,” or “If you don’t have a DNR order, health-care workers are legally required to try to resuscitate you.” You can also offer to discuss your own wishes first. For instance, “I don’t want you to wonder about my wishes, so that’s why I want to talk about this.”

One final point: Once you and your loved ones have completed the legal documents you decide are necessary, make sure several people know where they are so they can be accessed when needed.

Euthanasia (Ob 8)

Euthanasia, or helping a person fulfill their wish to die, can happen in two ways: voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Voluntary euthanasia refers to helping someone fulfill their wish to die by acting in such a way to help that person’s life end. Euthanasia can be by passive euthanasia, such as no longer feeding someone or giving them food. While voluntary euthanasia involves administering the deadly drug for a patient upon their request, the practice of prescribing drugs that are self-administered is sometimes referred to as physician-assisted suicide.

Physician-assisted suicide involves active euthanasia and occurs when a physician prescribes the means by which a person can end his or her own life. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in six states in the U.S., Canada, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and Belgium. The person seeking physician-assisted suicide for US states must be: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) have six or less months until expected death, and (3) obtain two oral (or least 15 days apart) and one written request from a physician (ProCon.org, 2016). In 2014, Belgium allows the right to die to those under the age of 18. Stricter conditions were put in place for children, including parental consent, the child must be suffering from a serious and incurable disease, the child must understand what euthanasia means, and the child’s death must be expected in the near future (Narayan, 2016). Physician-assisted suicides, however, are rare. Since 1997 when the law was passed in Oregon, 1545 people had lethal prescriptions written and 991 patients had died from the medication by the end of 2015 (Oregon Public Health Division, 2016).

The brain tumor was ending Brittany’s life. The option of living was no longer available to her. She chose between two different methods of dying. One method would be gentle, peaceful. The other would result in being tortured to death by the increasingly intense symptoms she was already experiencing: unrelenting pain, nausea, sleep deprivation, seizures, and impending blindness and paralysis. Those were her reasons for moving to Oregon to have this option available to her. (Diaz, 2019, pp. 8–9)

Table. Eleven States with Legal Physician-Assisted Suicide

| State | Date Passed |

| Oregon | Passed 11/8/1994, but enacted 10/27/1997 |

| Washington | 11/4/2008 |

| Montana | 12/31/2009 |

| Vermont | 5/20/2013 |

| California | 10/5/2015 |

| D.C. | 10/5/2016 |

| Colorado | 11/8/2016 |

| Hawaii | 4/5/2018 |

| New Jersey | 3/25/2019 |

| Maine | 6/12/2019 |

| New Mexico | 4/8/2021 |

The practice of physician-assisted suicide is certainly controversial with religious, legal, ethical, and medical experts weighing in with opinions. The main areas where there is a disagreement between those who support physician-assisted suicide and those who do not include: (1) whether a person has the legal right to die, (2) whether active euthanasia would become a “slippery slope” and start a trend to legalize deaths for individuals who may be disabled or unable to give consent, (3) how to interpret the Hippocratic Oath and what it exactly means for physicians to do no harm, (4) whether the government should be involved in end-of-life decisions, and (5) specific religious restrictions against deliberately ending a life (ProCon.org, 2016). Not surprisingly, there are strong opinions on both sides of this topic.

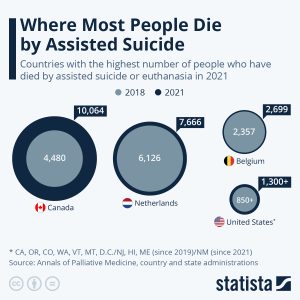

Assisted suicide and euthanasia are being legalized in an increasing number of countries and in those places where the practice has been allowed, the number of people who die with assistance is rising. The number of people dying with assistance has been rising much faster in Canada over the past three years than in other countries where assisted suicide or euthanasia are legal. The Netherlands and Belgium which, like Canada, allow both have seen numbers rise more slowly. Assisted dying has been legal there since the early 2000s, however, Canada legalized it in 2015. In 2021, assisted dying accounted for 3.3 percent of all deaths in Canada. The United States also saw a somewhat faster rise in those dying by self-administered physician-assisted suicide over the past four years (euthanasia is not legal in the U.S.). This was also aided by the fact that four states – New Jersey, Hawaii, Maine and New Mexico – legalized it between 2018 and 2021, while two more populous ones, Colorado and California, started the practice in 2016. Switzerland is another practitioner of physician-assisted suicide, but not euthanasia. Assisted dying is also legal or will become so soon in Luxembourg, Colombia, Spain, Austria, New Zealand and most Australian states.

Countries with Legal Euthanasia or Assisted Dying

- Netherlands

- Belgium

- Luxembourg

- Canada

- Colombia

- Spain

- New Zealand

- Portugal

- Switzerland (assisted suicide only)

- Australia (in all states)

- United States (only 11 states)

Euthanasia and assisted dying laws vary across the globe, with a limited number of countries and jurisdictions allowing some form of the practice. For more information visit, the World Federation of Right to Die Societies’ World Map, https://wfrtds.org/worldmap/

Cultural Differences in End-of-Life Decisions

According to Searight and Gafford (2005a), cultural factors strongly influence how doctors, other health care providers, and family members communicate bad news to patients, the expectations regarding who makes the health care decisions, and attitudes about end-of-life care. In the United States, doctors take the approach that patients should be told the truth about their health. Outside the United States and among certain racial and ethnic groups within the United States, doctors and family members may conceal the full nature of a terminal illness as revealing such information is viewed as potentially harmful to the patient, or at the very least, is seen as disrespectful and impolite. Holland et al. (1987) found that many doctors in Japan and in numerous African nations used terms such as “mass,” “growth,” and “unclean tissue” rather than referring to cancer when discussing the illness to patients and their families. Family members actively protect terminally ill patients from knowing about their illness in many Hispanic, Chinese, and Pakistani cultures (Kaufert & Putsch, 1997; Herndon & Joyce, 2004). In the United States, we view the patient as autonomous in health care decisions (Searight & Gafford, 2005a), while in other nations the family or community plays the main role, or decisions are made primarily by medical professionals, or the doctors in concert with the family make the decisions for the patient. For instance, in comparison to European Americans and African Americans, Koreans and Mexican-Americans are more likely to view family members as the decision makers rather than just the patient (Berger, 1998; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In many Asian cultures, illness is viewed as a “family event,” not just something that impacts the individual patient (Candib, 2002). Thus, there is an expectation that the family has a say in the health care decisions. As many cultures attribute high regard and respect for doctors, patients and families may defer some of the end-of-life decision making to the medical professionals (Searight & Gafford, 2005b).

According to a Pew Research Center Survey (Lipka, 2014), while death may not be a comfortable topic to ponder, 37% of their survey respondents had given a great deal of thought about their end-of-life wishes, with 35% having put these in writing. Yet, over 25% had given no thought to this issue. Lipka (2014) also found that there were clear racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life wishes. Whites are more likely than Blacks and Hispanics to prefer to have treatment stopped if they have a terminal illness. While the majority of Blacks (61%) and Hispanics (55%) prefer that everything be done to keep them alive. Searight and Gafford (2005a) suggest that the low rate of completion of advance directives among non-whites may reflect a distrust of the U.S. healthcare system as a result of the health care disparities non-whites have experienced. Among Hispanics, patients may also be reluctant to select a single family member to be responsible for end-of-life decisions out of a concern of isolating the person named and of offending other family members, as this is commonly seen as a “family responsibility” (Morrison et al., 1998).

WHAT DO YOU THINK? Brain Dead and on Life Support

What would you do if your spouse or loved one was declared brain dead but his or her body was being kept alive by medical equipment? Whose decision should it be to remove a feeding tube? Should medical care costs be a factor?

On February 25, 1990, a Florida woman named Terri Schiavo went into cardiac arrest, apparently triggered by a bulimic episode. She was eventually revived, but her brain had been deprived of oxygen for a long time. Brain scans indicated that there was no activity in her cerebral cortex, and she suffered from severe and permanent cerebral atrophy. Basically, Schiavo was in a vegetative state. Medical professionals determined that she would never again be able to move, talk, or respond in any way. To remain alive, she required a feeding tube, and there was no chance that her situation would ever improve.

On occasion, Schiavo’s eyes would move, and sometimes she would groan. Despite the doctors’ insistence to the contrary, her parents believed that these were signs that she was trying to communicate with them.

After 12 years, Schiavo’s husband argued that his wife would not have wanted to be kept alive with no feelings, sensations, or brain activity. Her parents, however, were very much against removing her feeding tube. Eventually, the case made its way to the courts, both in the state of Florida and at the federal level. By 2005, the courts found in favor of Schiavo’s husband, and the feeding tube was removed on March 18, 2005. Schiavo died 13 days later.

Why did Schiavo’s eyes sometimes move, and why did she groan? Although the parts of her brain that control thought, voluntary movement, and feeling were completely damaged, her brainstem was still intact. Her medulla and pons maintained her breathing and caused involuntary movements of her eyes and the occasional groans. Over the 15-year period that she was on a feeding tube, Schiavo’s medical costs may have topped $7 million (Arnst, 2003).

These questions were brought to popular conscience decades ago in the case of Terri Schiavo, and they have persisted. In 2013, a 13-year-old girl who suffered complications after tonsil surgery was declared brain dead. There was a battle between her family, who wanted her to remain on life support, and the hospital’s policies regarding persons declared brain dead. In another complicated 2013–14 case in Texas, a pregnant EMT professional declared brain dead was kept alive for weeks, despite her spouse’s directives, which were based on her wishes should this situation arise. In this case, state laws designed to protect an unborn fetus came into consideration until doctors determined the fetus unviable.

Decisions surrounding the medical response to patients declared brain dead are complex. What do you think about these issues?

Rituals After Death

Funeral rites are expressions of loss that reflect personal and cultural beliefs about the meaning of death and the afterlife. Ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and duty to those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. Although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one’s life as a survivor.

Many cultures have rituals to mark someone’s death and build meaning from their passing. Some are secular ceremonies that gather people together, while others have religious significance. Some serve primarily to support the surviving family, while others sustain the memory of ancestors, such as Shinto and Buddhist shrines and the Mexican Day of the Dead (McCoyd et al., 2021). In southern Ghana, some people are buried in elaborate “fantasy coffins” (abebuu adekai) that commemorate aspects of the person’s life, representing the belief that the afterlife is the same as this one (Gundlach, 2017; Potocnik & Adum-Kyeremeh, 2022).

Remembering and honoring the dead does not always involve official rituals from a particular culture or religious belief. For some, a ritual may be gathering friends to share memories and stories of the person’s life or toasting to their memory with a small group of close loved ones.

Religious Rituals After Death

The following are some of the religious practices regarding death, however, individual religious interpretations and practices may occur (Dresser & Wasserman, 2010; Schechter, 2009).

Buddhism: Buddhism views death as a natural part of life’s cycle, emphasizing the impermanence of all things. Cremation is the most common practice. Funeral rites often involve monks chanting sutras and leading meditation to guide the deceased’s spirit. Practices can vary widely among different Buddhist traditions, reflecting the diversity of beliefs and cultural influences within Buddhism.

Hindu: Hinduism, with its belief in reincarnation, approaches death as a transition in the soul’s journey. Funeral rites are typically accelerated to aid this transition. Cremation is the most common practice, with the body being washed, anointed, and adorned before being placed on a decorated pyre. Ashes are often collected and dispersed in a holy river. A traditional 13-day mourning period follows, with specific rituals and observances on certain days. Shraddha, an important ceremony performed after cremation, involves offerings made to the deceased’s ancestors to ensure their well-being in the afterlife.

Judaism: Judaism encompasses diverse practices related to death, varying among Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform branches. In Orthodox tradition, the deceased undergoes Tahara, a ritual purification process performed by the Chevra Kadisha (burial society). The body is then wrapped in a simple white shroud and placed in a plain wooden coffin. Burial occurs as soon as possible after death, accompanied by a service with prayers and a eulogy. Shiva, the seven-day mourning period, follows, with family members gathering to receive visitors and observe specific customs. This is often referred to as “sitting shiva.” Kriah, the symbolic tearing of clothing, is also a traditional expression of grief.

Muslim: Islam emphasizes community involvement in funeral rites. The deceased is washed and wrapped in a plain white shroud called a kaftan. The Janazah, the Islamic funeral prayer, is performed by the community, followed by burial. The body is placed directly in the earth without a casket, positioned on its right side facing Mecca. Embalming and cremation are generally forbidden in Islamic tradition. Widows observe a three-day mourning period, while close family members mourn for 40 days.

Roman Catholic: Catholic funerals are often preceded by the Anointing of the Sick, a sacrament where a priest anoints the ill person with oil and offers prayers for healing and comfort. Viaticum, the final Eucharist (Communion), may also be given to the dying. The funeral rites typically involve a Vigil, a gathering where the body is present and prayers and eulogies are offered. This is followed by a Funeral Mass with readings, liturgy, and Communion. The final stage of the funeral takes place at the cemetery, where the grave is blessed and prayers are recited.

Bereavement and Grief (Ob 9)

The terms grief, bereavement, and mourning are often used interchangeably, however, they have different meanings. Grief is the normal process of reacting to a loss. Grief can be in response to a physical loss, such as a death, or a social loss including a relationship or job. Bereavement is the period after a loss during which grief and mourning occur. Bereavement describes the state of being following the death of someone (bereavement leave). The time spent in bereavement for the loss of a loved one depends on the circumstances of the loss and the level of attachment to the person who died.

Mourning is the process by which people adapt to a loss. Mourning is greatly influenced by cultural beliefs, practices, and rituals (Casarett et al., 2001).

Four Tasks of Mourning: Worden (2008) identified four tasks that facilitate the mourning process. Worden believes that all four tasks must be completed, but they may be completed in any order and for varying amounts of time. These tasks include:

- Acceptance that the loss has occurred

- Working through the pain of grief

- Adjusting to life without the deceased

- Starting a new life while still maintaining a connection with the deceased

Mourning and funeral rites are expressions of loss that reflect personal and cultural beliefs about the meaning of death and the afterlife. When asked what type of funeral they would like to have, students responded in a variety of ways; each expressing both their personal beliefs and values and those of their culture.

I would like the service to be at a Baptist church, preferably my Uncle Ike’s small church. The service should be a celebration of life . . . I would like there to be hymns sung by my family members, including my favorite one, “It is Well With My Soul”. . .At the end, I would like the message of salvation to be given to the attendees and an altar call for anyone who would like to give their life to Christ. . .

I want a very inexpensive funeral-the bare minimum, only one vase of flowers, no viewing of the remains and no long period of mourning from my remaining family . . . funeral expenses are extremely overpriced and out of hand. . .

When I die, I would want my family members, friends, and other relatives to dress my body as it is usually done in my country, Ghana. Lay my dressed body in an open space in my house at the night prior to the funeral ceremony for my loved ones to walk around my body and mourn for me. . .

I would like to be buried right away after I die because I don’t want my family and friends to see my dead body and to be scared.

In my family we have always had the traditional ceremony-coffin, grave, tombstone, etc. But I have considered cremation and still ponder which method is more favorable. Unlike cremation, when you are ‘buried’ somewhere and family members have to make a special trip to visit, cremation is a little more personal because you can still be in the home with your loved ones . . .

I would like to have some of my favorite songs played....I will have a list made ahead of time. I want a peaceful and joyful ceremony and I want my family and close friends to gather to support one another. At the end of the celebration, I want everyone to go to the Thirsty Whale for a beer and Spang’s for pizza!

When I die, I want to be cremated . . . I want it the way we do it in our culture. I want to have a three day funeral and on the fourth day, it would be my burial/cremation day . . . I want everyone to wear white instead of black, which means they already let go of me. I also want to have a mass on my cremation day.

When I die, I would like to have a befitting burial ceremony as it is done in my Igbo customs. I chose this kind of funeral ceremony because that is what every average person wishes to have.

I want to be cremated . . . I want all attendees wearing their favorite color and I would like the song “Riders on the Storm” to be played . . . I truly hope all the attendees will appreciate the bass. At the end of this simple, short service, attendees will be given multi-colored helium–filled balloons . . . released to signify my release from this earth. . .They will be invited back to the house for ice cream cones, cheese popcorn and a wide variety of other treats and much, much, much rock music . . .

I want to be cremated when I die. To me, it’s not just my culture to do so but it’s more peaceful to put my remains or ashes to the world. Let it free and not stuck in a casket.

Ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and duty to those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. And although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one’s life as a survivor.

Grief

Grief is the psychological, physical, and emotional experience of loss. This includes Kübler-Ross five themes of of grief (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Grief reactions vary depending on whether a loss was anticipated or unexpected (parents do not expect to lose their children, for example), and whether or not it occurred suddenly or after a long illness, and whether or not the survivor feels responsible for the death.

Struggling with the question of responsibility is particularly felt by those who lose a loved one to suicide. There are numerous survivors for every suicide, resulting in 4.5 million survivors of suicide in the United States (American Association of Suicidology, 2007). These survivors may torment themselves with endless “what ifs” in order to make sense of the loss and reduce feelings of guilt. And family members may also hold one another responsible for the loss. The same may be true for any sudden or unexpected death making conflict an added dimension to grief. Much of this laying of responsibility is an effort to think that we have some control over these losses; the assumption being that if we do not repeat the same mistakes, we can control what happens in our life.

Anticipatory grief occurs when a death is expected and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss. Anticipatory grief can include the same denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance experienced in loss. This can make adjustment after a loss somewhat easier, although the stages of loss will be experienced again after the death (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). A death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over. The exhausting process of caring for someone who is ill is over.

Disenfranchised grief may be experienced by those who have to hide the circumstances of their loss or whose grief goes unrecognized by others. Loss of an ex-spouse, lover, or pet may be examples of disenfranchised grief.

Yet grief continues as long as there is a loss. It has been said that intense grief lasts about two years or less, but grief is felt throughout life. One loss triggers the feelings that surround another. People grieve with varied intensity throughout the remainder of their lives. It does not end. But it eventually becomes something that a person has learned to live with. As long as we experience loss, we experience grief (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005).

There are layers of grief. Initial denial, marked by shock and disbelief in the weeks following a loss may become an expectation that the loved one will walk in the door. And anger directed toward those who could not save our loved one’s life, may become anger that life did not turn out as we expected. There is no right way to grieve. A bereavement counselor expressed it well by saying that grief touches us on the shoulder from time to time throughout life.

Grief and mixed emotions go hand in hand. A sense of relief is accompanied by regrets and periods of reminiscing about our loved ones are interspersed with feeling haunted by them in death. Our outward expressions of loss are also sometimes contradictory. We want to move on but at the same time are saddened by going through a loved one’s possessions and giving them away. We may no longer feel sexual arousal or we may want sex to feel connected and alive. We need others to befriend us but may get angry at their attempts to console us. These contradictions are normal and we need to allow ourselves and others to grieve in their own time and in their own ways.

The “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” is the modern world (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005, p. 205). We are asked to grieve privately, quickly, and to medicate our suffering. Employers grant us 3 to 5 days for bereavement, if our loss is that of an immediate family member. And such leaves are sometimes limited to no more than one per year. Yet grief takes much longer and the bereaved are seldom ready to perform well on the job. Obviously, life does have to continue. But Kubler-Ross and Kessler suggest that contemporary American society would do well to acknowledge and make more caring accommodations to those who are in grief.

Dual-Process Model of Grieving: The dual-process model takes into consideration that bereaved individuals move back and forth between grieving and preparing for life without their loved one (Stroebe & Schut, 2001; Stroebe et al., 2005; Stroebe et al., 2013, 2017). This model focuses on a loss orientation, which emphasizes the feelings of loss and yearning for the deceased and a restoration orientation, which centers on the grieving individual re-establishing roles and activities they had prior to the death of their loved one. When oriented toward loss grieving individuals look back, and when oriented toward restoration they look forward. As one cannot look both back and forward at the same time, a bereaved person must shift back and forth between the two. Both orientations facilitate normal grieving and interact until bereavement has completed.

Contextual Influences on Grieving and Mourning

Grief is shaped by several factors, including the age at which death occurs, the relationship between the deceased and survivors, and the dying trajectory. The death of a child or young adult is often harder to cope with than that of an older adult, as it defies expectations of the human lifespan. When an infant or young child dies, typical mourning rituals may not take place, affecting how families process grief. Parents may avoid sharing their feelings with each other to protect one another, which can intensify their grief, and they may also struggle to care for surviving children or become overprotective. The closeness or conflict in the relationship with the deceased also influences grief, and even healthcare providers can experience significant, though often unacknowledged, grief. Sudden deaths, particularly of children, tend to elicit more intense grief responses due to the lack of time for emotional preparation. The cause of death, such as suicide, may be linked to stronger grief reactions, although this is not always consistent and may relate more to the suddenness of the loss. In cases of dementia, caregivers experience grief in multiple ways, including the loss of communication and relationship changes, which are compounded by the inability to share memories and feelings.

How to Support a Loved One who is Grieving: Supporting someone who is grieving requires empathy, patience, and a willingness to simply be present. Research emphasizes the importance of active listening, allowing the griever to express their emotions without judgment or interruption (Prigerson et al., 2008). Offer practical assistance with daily tasks, such as cooking, cleaning, or childcare, as grief can often make these feel overwhelming (Stroebe & Schut, 2010). Avoid offering unsolicited advice or minimizing their loss with clichés; instead, validate their feelings and acknowledge the uniqueness of their grief journey (Neimeyer, 2001). Remember that grief is not linear, and continued support over time, even after the initial period of mourning, is crucial for healing (Bonanno & Kaltman, 2001). Finally, encourage the griever to seek professional help if they are struggling to cope, as therapy can provide valuable tools and support during this difficult time (Currier et al., 2008).

Conclusion

Death, while a universal human experience, is deeply intertwined with cultural beliefs, values, and practices (Gutiérrez et al., 2019). As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, understanding these diverse perspectives becomes ever more crucial. By exploring our own anxieties about death and delving into the complexities of grief across cultures, we can develop greater empathy and compassion for ourselves and others as we navigate this inevitable aspect of life.