Learning Objectives

- Understand the difference between groups and teams.

- Understand the factors leading to the rise in the use of teams.

- Understand how tasks and roles affect teams.

- Identify different types of teams.

- Identify team design considerations.

Effective teams give companies a significant competitive advantage. In a high-functioning team, the sum is truly greater than the parts. Team members not only benefit from one another’s diverse experiences and perspectives but also stimulate each other’s creativity. Plus, for many people, working in a team can be more fun than working alone. Let’s take a closer look at what a team is, the different team characteristics, types of teams companies use, and how to design effective teams.

Differences Between Groups and Teams

Organizations consist of groups of people. What exactly is the difference between a group and a team? A group is a collection of individuals. Within an organization, groups might consist of project-related groups such as a product group or division or they can encompass an entire store or branch of a company. The performance of a group consists of the inputs of the group minus any process losses such as the quality of a product, ramp-up time to production, or the sales for a given month. Process loss is any aspect of group interaction that inhibits group functioning.

Why do we say group instead of team? A collection of people is not a team, though they may learn to function in that way. A team is a particular type of group: a cohesive coalition of people working together to achieve mutual goals. Being on a team does not equate to a total suppression of personal agendas, but it does require a commitment to the vision and involves each individual working toward accomplishing the team’s objective. Teams differ from other types of groups in that members are focused on a joint goal or product, such as a presentation, discussing a topic, writing a report, creating a new design or prototype, or winning a team Olympic medal. Moreover, teams also tend to be defined by their relatively smaller size. For instance, according to one definition, “A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable.”Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1993). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Boston: Harvard Business School.

The purpose of assembling a team is to accomplish larger, more complex goals than what would be possible for an individual working alone or even the simple sum of several individuals working independently. Teamwork is also needed in cases where multiple skills are tapped or where buy-in is required from several individuals. Teams can, but do not always, provide improved performance. Working together to further a team agenda seems to increase mutual cooperation between what are often competing factions. The aim and purpose of a team is to perform, get results, and achieve victory in the workplace. The best managers are those who can gather together a group of individuals and mold them into an effective team.

The key properties of a true team include collaborative action where, along with a common goal, teams have collaborative tasks. Conversely, in a group, individuals are responsible only for their own area. They also share the rewards of strong team performance with their compensation based on shared outcomes. Compensation of individuals must be based primarily on a shared outcome, not individual performance. Members are also willing to sacrifice for the common good in which individuals give up scarce resources for the common good instead of competing for those resources. For example, teams occur in sports such as soccer and basketball, in which the individuals actively help each other, forgo their own chance to score by passing the ball, and win or lose collectively as a team.

Teams in Organizations

The early 1990s saw a dramatic rise in the use of teams within organizations, along with dramatic results such as the Miller Brewing Company increasing productivity 30% in the plants that used self-directed teams compared with those that used the traditional organization. This same method allowed Texas Instruments in Malaysia to reduce defects from 100 parts per million to 20 parts per million. In addition, Westinghouse reduced its cycle time from 12 weeks to 2 weeks, and Harris Electronics was able to achieve an 18% reduction in costs. Welins, R., Byham, W., & Dixon, G. (1994). Inside Teams. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. The team method has served countless companies over the years through both quantifiable improvements and more subtle individual worker-related benefits.

Companies such as Square D, a maker of circuit breakers, switched to self-directed teams and found that overtime on machines like the punch press dropped 70% under teams. Productivity increased because the setup operators were able to manipulate the work in much more effective ways than a supervisor could dictate. Moskal, B. (1988, June 20). Supervisors, begone! Industry Week, p. 32. In 2001, clothing retailer Chico’s FAS was looking to grow its business. The company hired Scott Edmonds as president, and two years later revenues had almost doubled from $378 million to $760 million. By 2006, revenues were $1.6 billion, and Chico’s had nine years of double-digit same-store sales growth. What did Edmonds do to get these results? He created a horizontal organization “ruled by high-performance teams with real decision-making clout and accountability for results, rather than by committees that pass decisions up to the next level or toss them over the wall into the nearest silo.”

The use of teams also began to increase because advances in technology have resulted in more complex systems that require contributions from multiple people across the organization. Overall, team-based organizations have more motivation and involvement, and teams can often accomplish more than individuals. Cannon-Bowers, J. A. and Salas, E. (2001, February). Team effectiveness and competencies. In W. Karwowski (Ed.), International encyclopedia of ergonomics and human factors (1383). London: CRC Press. It is no wonder organizations are relying on teams more and more.

Do We Need a Team?

Teams are not a cure-all for organizations. To determine whether a team is needed, organizations should consider whether a variety of knowledge, skills, and abilities are needed, whether ideas and feedback are needed from different groups within the organization, how interdependent the tasks are, if wide cooperation is needed to get things done, and whether the organization would benefit from shared goals. Rees, F. (1997). Teamwork from start to finish. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. If the answer to these questions is “yes,” then a team or teams might make sense. For example, research shows that the more team members perceive that outcomes are interdependent, the better they share information and the better they perform. De Dreu, C. K. W. (2007). Cooperative outcome interdependence, task reflexivity, and team effectiveness: A motivated information processing perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 628–638.

Team Tasks and Roles

Teams differ in terms of the tasks they are trying to accomplish and the roles team members play.

As early as the 1970s, J. R. Hackman identified three major classes of tasks: (1) production tasks, (2) idea generation tasks, and (3) problem-solving tasks. Hackman, J. R. (1976). Group influences on individuals. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago: Rand-McNally. Production tasks include actually making something, such as a building, a product, or a marketing plan. Idea generation tasks deal with creative tasks, such as brainstorming a new direction or creating a new process. Problem-solving tasks refer to coming up with plans for actions and making decisions, both facets of managerial P-O-L-C functions (planning and leading). For example, a team may be charged with coming up with a new marketing slogan, which is an idea generation task, while another team might be asked to manage an entire line of products, including making decisions about products to produce, managing the production of the product lines, marketing them, and staffing their division. The second team has all three types of tasks to accomplish at different points in time.

Task Interdependence

Another key to understanding how tasks are related to teams is to understand their level of task interdependence. Task interdependence refers to the degree that team members depend on one another to get information, support, or materials from other team members to be effective. Research shows that self-managing teams are most effective when their tasks are highly interdependent. Langfred, C. W. (2005). Autonomy and performance in teams: The multilevel moderating effect of task interdependence. Journal of Management, 31, 513–529; Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Bradway, L. K. (1997). Task interdependence as a moderator of the relation between group control and performance. Human Relations, 50, 169–181.

There are three types of task interdependence. Pooled interdependence exists when team members may work independently and simply combine their efforts to create the team’s output. For example, when students meet to divide the sections of a research paper and one person simply puts all the sections together to create one paper, the team is using the pooled interdependence model. However, they might decide that it makes more sense to start with one person writing the introduction of their research paper, then the second person reads what was written by the first person and, drawing from this section, writes about the findings within the paper. Using the findings section, the third person writes the conclusions. If one person’s output becomes another person’s input, the team would be experiencing sequential interdependence. And finally, if the student team decided that in order to create a top notch research paper they should work together on each phase of the research paper so that their best ideas would be captured at each stage, they would be undertaking reciprocal interdependence. Another important type of interdependence that is not specific to the task itself is outcome interdependence, where the rewards that an individual receives depend on the performance of others.

Team Roles

While relatively little research has been conducted on team roles, recent studies show that individuals who are more aware of team roles and the behavior required for each role perform better than individuals that do not. This fact remains true for both student project teams as well as work teams, even after accounting for intelligence and personality. Mumford, T. V., Van Iddekinge, C. H., Morgeson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2008). The team role test: Development and validation of a team role knowledge situational judgment test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 250–267. Early research found that teams tend to have two categories of roles: those related to the tasks at hand and those related to the team’s functioning. For example, teams that only focus on production at all costs may be successful in the short run, but if they pay no attention to how team members feel about working 70 hours a week, they are likely to experience high turnover.

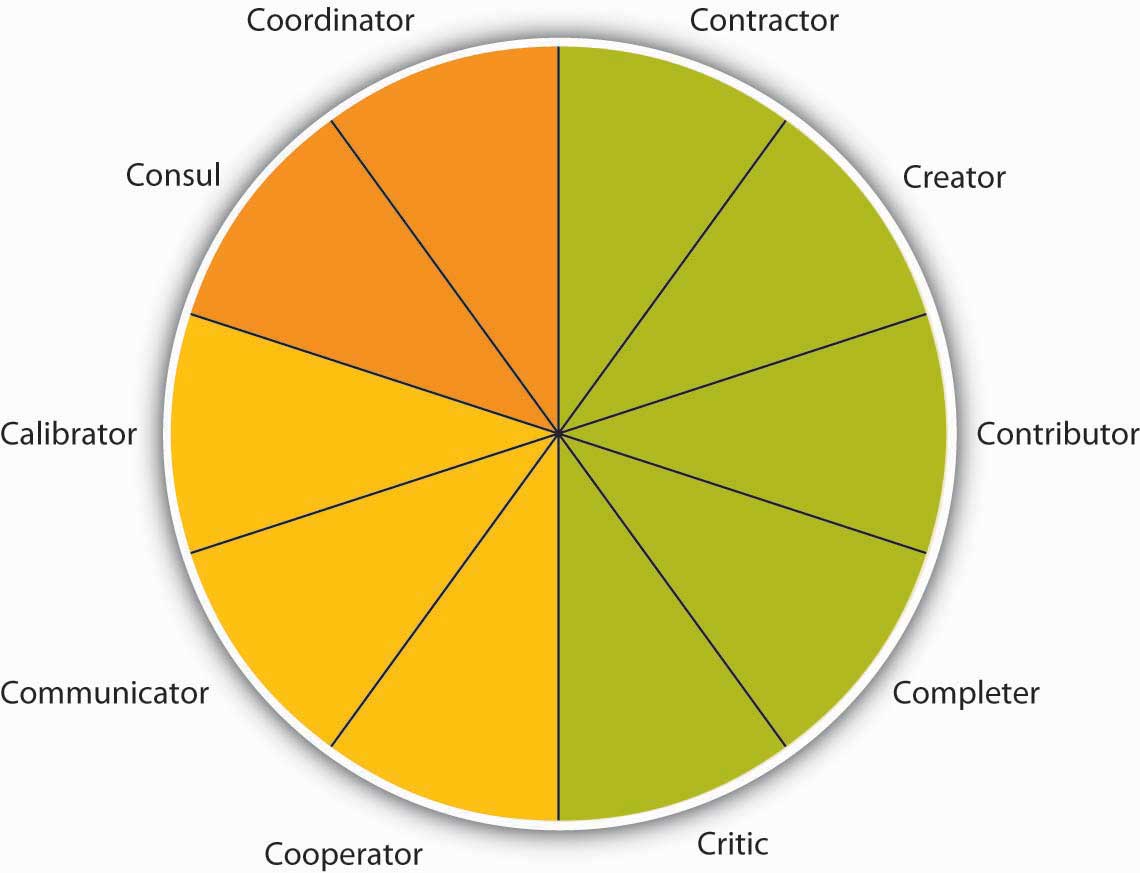

On the basis of decades of research on teams, 10 key roles have been identified. Bales, R. F. (1950). Interaction process analysis: A method for the study of small groups. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley; Benne, K. D., & Sheats, P. (1948). Functional roles of group members. Journal of Social Issues, 4, 41–49; Belbin, R. M. (1993). Management teams: Why they succeed or fail. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. Team leadership is effective when leaders are able to adapt the roles they are contributing to or asking others to contribute to fit what the team needs, given its stage and the tasks at hand.Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., McHugh, P. P., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (1996). A dynamic theory of leadership and team effectiveness: Developmental and task contingent roles. In G. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resource management (Vol. 14, pp. 253–305). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (1996). Team leadership and development: Theory, principles, and guidelines for training leaders and teams. In M. M. Beyerlein, D. A. Johnson, & S. T. Beyerlein (Eds.), Advances in interdisciplinary studies of work teams (Vol. 3, pp. 253–291). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Ineffective leaders might always engage in the same task role behaviors when what they really need to do is focus on social roles, put disagreements aside, and get back to work. While these behaviors can be effective from time to time, if the team doesn’t modify its role behaviors as things change, they most likely will not be effective.

REFERENCES

Mumford, T. V., Van Iddekinge, C. H., Morgeson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2008). The team role test: Development and validation of a team role knowledge situational judgment test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 250–267; Mumford, T. V., Campion, M. A., & Morgeson, F. P. (2006). Situational judgments in work teams: A team role typology. In J. A. Weekley & R. E. Ployhart (Eds.), Situational judgment tests: Theory, measurement (pp. 319–343). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.