7. Privilege & Biases

7.4: Address Your Biases

As we discussed in Chapter 3, biases are complicated psychological products derived from our development and experiences, education, culture, beliefs, and/or social interactions. However, biases can drive disrespectful behaviours that harm different groups of people and can result in situations like toxic work-place cultures, low sense of belonging, diminished employee satisfaction levels and reduced productivity and innovation. In this chapter, we will showcase some examples of microaggressions and instances of biases that commonly occur in post-secondary institutions and encourage you to explore and brainstorm ways to be an effective upstander. How can you raise awareness of unconscious biases for yourself and for others? What are some of the steps for intervention?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Address your own biases;

- Define different forms of microaggressions; and

- Practice how to work with your peers to gain self-awareness.

Introduction

Although you consider yourself to be a fair and just person, you may have been surprised by your scores after having completed the Implicit Association Test in the last chapter. Don’t worry, you have already taken an important first step in recognizing your own unconscious biases. Sometimes people think unconscious biases only apply to those with power and privilege, but that is not true at all. Our own little iceberg of biases might differ in size and shape, but each one of us have and demonstrate unconscious biases in our everyday life.

Even though we all have our own biases, we must work hard to dismantle them. Unconscious biases lead to unfair outcomes in our society. For example, there is overwhelming evidence suggesting that implicit bias could skew school teachers’ expectations for students’ academic achievements, and that Black students are more likely to be suspended, expelled, or punished harshly (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015; van den Bergh et al., 2010; Wright, 2016). Unconscious racial biases have also been found to result in differential pain medication prescription (Hoffman et al., 2016) and patient care (Cooper et al., 2012; Hagiwara et al., 2014). Evidence showing the impact of unconscious biases can also be found in academic, business, criminal justice, film industry, politics, leadership, and education system practices (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012, Staats et al., 2017).

Act on Unconscious Biases

Let us take a minute to reflect on the steps proposed in this video.

- Recognize that unconscious biases exist, slow down your thought process and take some deep breaths. Examine your behaviour: ask if you interact with your peers and colleagues differently based on their specific identity markers? (Race, gender, social class, age, sexual orientation, religion affiliation, place of origin or education level). You can also try a little mental exercise where you change certain aspects of your peers’ identities in your head, and reflect on whether you would have behaved the same way or differently? Try out different possibilities. Perhaps you could revisit the same IAT or try out a couple of different topics to get a better understanding of your own unconscious mind.

- When confronting unexpected situations, take a moment to examine your own behaviour. Ask yourself some questions: how would you have handled an interaction if, for instance, your classmate or colleague looked like you? Or if your classmate/colleague did not look like you? Ask yourself whether you have made assumptions or judgments in the ways in which you interact with others. Have you considered other points of view? Have you had an open and honest conversation with your peers? Listen to what they have to say and challenge yourself to unlearn cultural narratives that have harmed your perception about individuals or social groups that are not like you.

If you still have that screenshot of your last IAT score, please open it up and take a few minutes to reflect. Can you recognize some biased attitude or behaviour towards different groups of people without meaning to? Think of your recent social interactions. Do you wish you could have done or said something differently or not at all?

Maybe you realized that during your interaction with your peers, you had some subtle but inappropriate behaviours, such as asking them “where are they really from?” or acting surprised when their true-self conflicts with your perceived stereotypes. These subtle, unintentionally harmful behaviours are examples of microaggressions.

Microaggression

You might have heard that sometimes people refer to microaggressions as mosquito bites. In this short video (2:46), “How microaggressions are like mosquito bites. Same Difference” by Fusion Comedy, you will find out why mosquito bites are a very fitting metaphor to describe microaggressions, as well as learn some examples of microaggressions, which are experienced by different groups of people every day:

There are three different types of microaggressions (Sue et al., 2007):

- Microassault is a deliberate and conscious derogative comment sent by a verbal or nonverbal message that is meant to hurt people’s feeling through name-calling and discriminatory actions. An example of a microassault could be calling someone racial slurs or prioritizing white supremacy.

- Microinsult is subtle snubs and insensitive comments that convey rudeness and demeans a person’s contributions, such as talking over a member of an equity-deserving group or “helping” a person with a disability without asking.

- Microinvalidation is subtle exclusion or negation of one’s thoughts, feelings or experiential reality, such as complimenting someone’s English even though English was their first language or asking a racial minority where they are really from.

Like acting on our unconscious biases, we can recognize and address microaggressions using the following self-awareness exercise:

- Intention: what was the intent of my behaviour?

- Assumption: what assumptions did I make?

- Impact: what was the impact? Keep in mind that intent does not supersede impact.

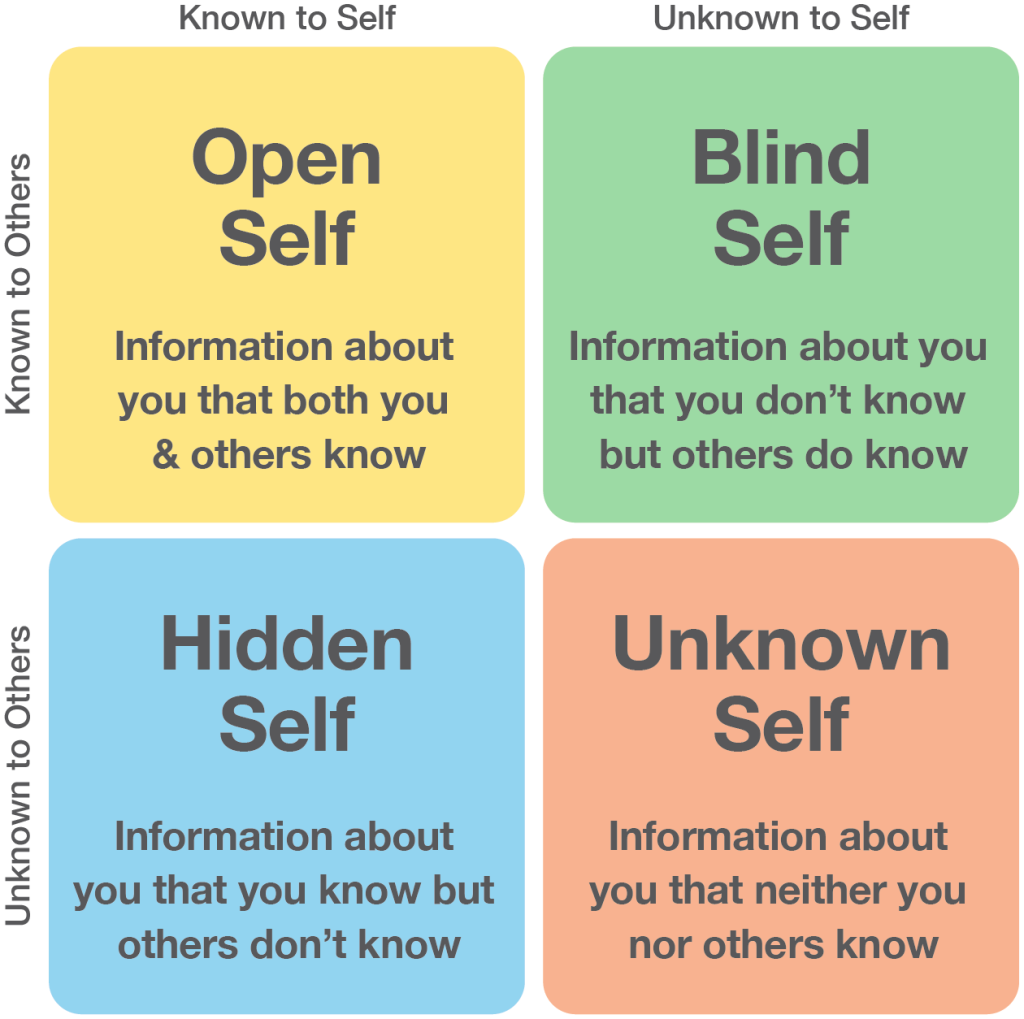

It is important to note that it is an ongoing continuous process to combat our own biases and microaggressions. It is not about making an occasional big step forward; it is about having consistent progress. Practising these self-reflection and self-awareness exercises in a group setting would help. Here, we adapted a classic Johari Window Model to help you through different discovery processes to uncover the unconscious biases within your EDI learning.

Self-Awareness (Johari Window Model)

The Johari Window model was developed by Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham in 1955 to understand self-awareness within a team through an exploratory activity that aims to increase the ‘open self’ area.

Summary and Self-Reflection

Biases, conscious or unconscious, can have a pervasive impact on others. Biases are inevitable – they are a psychological product cultivated from our development and our lived experiences as our brain seeks patterns and to take shortcuts. But biases can be addressed and unlearned. It takes time, effort, constant learning, self-criticizing, and reflection to keep track of our motives and progress. Get out of your comfort zone to broaden your experiences. Be accountable for your actions and the actions of others.

The next time you talk to someone, whether it’s a family member or a colleague, keep an inventory of your language and your actions, and ask yourself:

- What were my assumptions?

- Would I respond differently if this was someone with a different identity profile?

- How would I make my language more neutral and inclusive?

- Did I give them the benefit of the doubt?

- How can I be a better listener?

- Is there something else I could’ve done different?

A small step forward can be big progress with long-lasting impacts. It takes all of us to work collaboratively to combat toxic schemas.

References

Cooper, L. A., Roter, D. L., Carson, K. A., Beach, M. C., Sabin, J. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Inui, T. S. (2012). The Associations of Clinicians’ Implicit Attitudes About Race With Medical Visit Communication and Patient Ratings of Interpersonal Care. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 979–987. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558

Hagiwara, N., Kashy, D. A., & Penner, L. A. (2014). A novel analytical strategy for patient–physician communication research: The one-with-many design. Patient Education and Counseling, 95(3), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.017

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Microaggression. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/microaggression

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(41), 16474–16479. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211286109

Okonofua, J. A., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2015). Two Strikes: Race and the Disciplining of Young Students. Psychological Science, 26(5), 617–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615570365

Staats, C., Capatosto, K., Tenney, L., & Mamo, S. (2017) State of the Science: Implicit Bias Review 2017.The Kirwan Institute. The Ohio State University.

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Wiley.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

van den Bergh, L., Denessen, E., Hornstra, L., Voeten, M., & Holland, R. W. (2010). The Implicit Prejudiced Attitudes of Teachers: Relations to Teacher Expectations and the Ethnic Achievement Gap. American Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 497–527. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209353594

Wright, R. A. (2016). Black Girls Matter, Too: A Gender and Race Examination of Implicit Bias in Ohio School Discipline Disparities. 2016, The Kirwan Institute, The Ohio State University

Image Credits

Chapter 4 Banner: Open Learning and Educational Support, University of Guelph/graphic

Chapter 4 Divider: Open Learning and Educational Support, University of Guelph/graphic

Figure 4.1 Johari Window Model: Open Learning and Educational Support, University of Guelph/graphic

Image Transcript

Figure 4.1 Johari Window Model

Johari Window Model

OPEN SELF (Known to Self and Others)

- Information about you that both you & others know.

BLIND SELF (Unknown to Self, Known to Others)

- Information about you that you don’t know but others do know.

HIDDEN SELF (Known to Self, Unknown to Others)

- Information about you that you know but others don’t know.

UNKNOWN SELF (Unknown to Self or Others)

- Information about you that neither you nor others know.