8. The Psychology of Racism, Stereotyping & Discrimination

Psychology of Racism

By Phia Salter , Glenn Adams, and Tuğçe Kurtiş Davidson College, University of Kansas, Prescott College

Thinking about racism as solely a problem among a certain set of biased or prejudiced individuals can lead us to underestimate the problem of racism. This module describes a systemic approach to understanding racism and the implications of such an approach in psychology. Systemic approaches emphasize the important roles historical, cultural, legal, political, and economic systems have in reproducing contemporary forms of racism. By engaging this module, students will be able to better understand the implications of a systemic (versus individualistic) approach in psychology for anti-racist research, anti-racist practices, and anti-racist interventions.

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish individual and systemic approaches to racism in psychology

- Understand race as a social construction and its historical and contemporary links to racism

- Learn about psychological mechanisms related to differences in perceptions of racism

- Understand the implications of a systemic approach to racism for research and intervention efforts

- Consider important connections between overlapping identities and oppression

Introduction

In 2020, Kennedy Mitchum–a recent college graduate–wrote a series of emails to the editors at Merriam-Webster dictionary, asking them to update their online definitions of racism. At the time, the definition–which had not been significantly revised in decades–contained three entries:

- Racism is “a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences reflect an inherent superiority of a particular race” (or, in other words: racial bigotry)

- Racism is “a doctrine or political program based on the assumption of racism and designed to execute its principles”. (Racism as “doctrine” highlights racism as a set of beliefs held by different political systems like Apartheid or groups like White Supremacists)

- Racism is “racial prejudice or discrimination.”

These definitions might be similar to the ways in which you think about racism. Indeed, these definitions are widely used and they frame everyday discussions of the topic. Thinking about racism as a problem among a certain set of biased or prejudiced people can lead us to underestimate the problem of racism. This is because it narrows the focus to individual acts motivated by hate or ignorance and it overlooks more systemic biases. In this module, we will discuss racism as a multifaceted and multi-level concept.

Different Understandings of Racism

In her email to the dictionary editors, Mitchum wrote, “Racism is not only prejudice against a certain race due to the color of a person’s skin, as it states in your dictionary. It is both prejudice combined with social and institutional power. It is a system of advantage based on skin color” (Hauser, 2020). Spurred by the exchange with Mitchum and the Black Lives Matter Protests in the summer of 2020, the editors updated their definition of racism which now has two entries. The first entry maintains the definition of racism as individual beliefs but the second now explicitly emphasizes racism as systemic oppression. This change is consistent with scholarship that defines racism as a system of advantage and disadvantage based on social, historical, and cultural constructions of race and ethnicity (Jones, 1997/1998; Tatum, 1997; Wellman, 1993).

Though this view is generally accepted by psychologists now, it has not always been the case. In psychology, the term racism has sometimes been used synonymously with prejudice (biased feelings or affect), stereotyping (biased thoughts and beliefs, or flawed generalizations), discrimination (differential or the absence of equal treatment), and bigotry (intolerance or hatred toward those with differing beliefs) (Adams et al., 2008a; Adams et al., 2008b). This approach reduces racism to its most basic parts at the individual level so that it can more easily be studied in a laboratory. However, it risks minimizing the institutional, systemic, and cultural processes that inform racism.

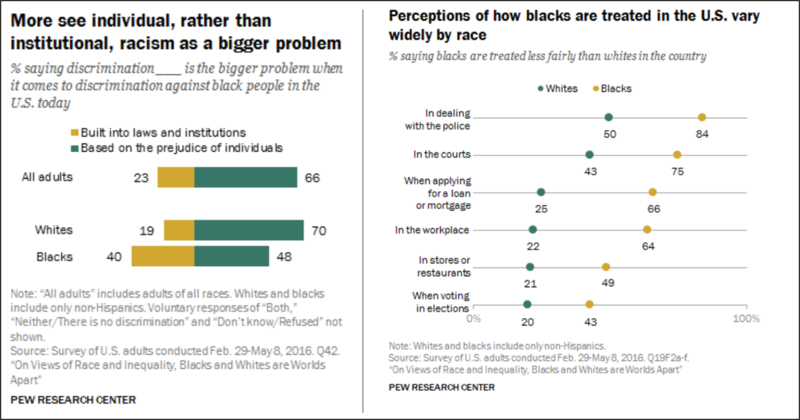

Research suggests that different understandings of racism—as a problem of individual bias versus a structurally embedded force—are not randomly distributed across people. In the United States, understanding of racism as individual bias is especially pronounced among White Americans (Blauner, 2019; Carter & Murphy, 2015; Sommers & Norton, 2006). For example, Figure 1 (left side) shows the results of polls (Pew Research Center, 2016) that generally find that White Americans are far more likely than Black Americans to define the problem of racism narrowly as discrimination “based on the prejudice of individuals.” Conversely, Black Americans are more likely than White Americans to define the problem of racism more broadly as discrimination “built into laws and institutions.” Beyond differences in the definition of racism, researchers have also noted group differences in perceptions of the role that racism plays in the modern world. Consider the results of another survey that also appear in Figure 1 (right side). Across several social issues, the percentage of participants who believe that racism impacts a wide range of social problems is much lower among White American than among Black American respondents.

Systemic Racism

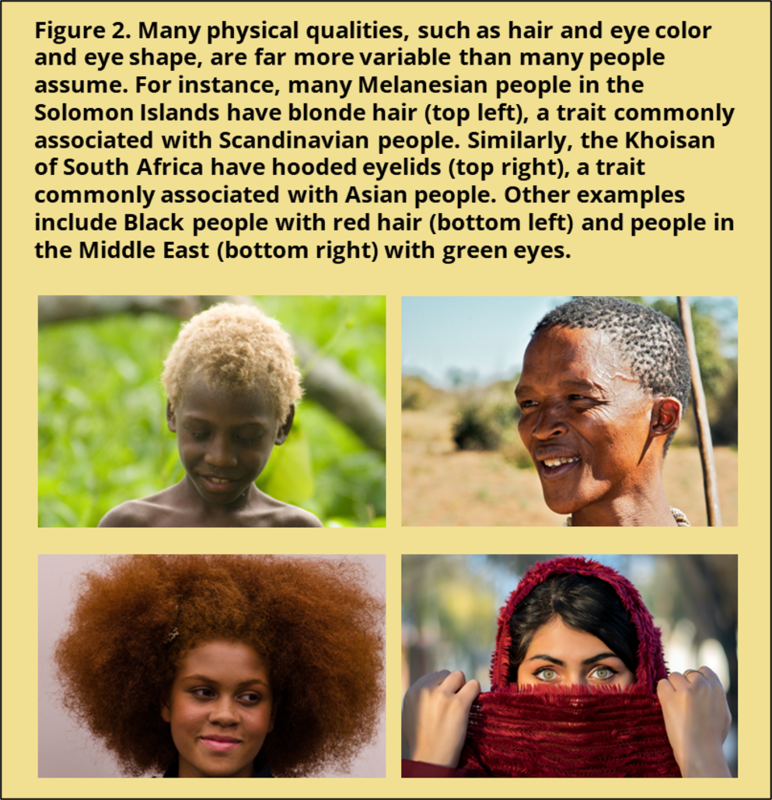

Systemic approaches to racism emphasize the particular roles that different societal factors—historical, cultural, legal, political, and economic—have played in organizing who is at the top or bottom of a society’s racial hierarchy (Salter et al., 2018) There are a few key ideas that are important to keep in mind for understanding racism as systemic. First, ‘race’ itself, is a social construct. Racial categories are arbitrary in that there is not substantial scientific evidence supporting a clear biological division of ‘races.’ Have you ever stopped to ask yourself why there are four or five common categories, but not 3, 29, or 101? Even though we treat racial categories as if they are true biological distinctions, they are not. Human beings share 99.9% of their genetic makeup (National Human Genome Research Institute, 2018). Most people have physical characteristics or phenotypes that could be associated with more than one racial group. In fact, there are no traits that are only present in one population or ‘race’. There are many expressions of traits found within and across different racial groups (see the images in Figure 2, for example). To say that race is an arbitrary social construct does not mean, however, that peoples’ race-based experiences are not real.

Second, racial categories were developed with intentions that have fluctuated over time. Racial categorizations have played a key role in dictating which people are marginalized. For example, upon their arrival in the British colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries, Irish Catholic immigrants were initially racialized as non-White, working and living alongside free and enslaved Black people (Ignatiev, 2012; Garner, 2007). As Celts, the Irish were considered a less-developed, uncivilized race relative to Anglo-Saxons and faced wide-spread discrimination in this context. However, with a rising population of enslaved Africans and a need to easily distinguish enslaved from free laborers, it became useful to expand the definition of whiteness (Garner, 2007). In the United States, actively defining and redefining who could be considered racially ‘White’ (and free) fortified the racial hierarchy and ultimately cemented enslaved status as tied to Blackness.

Modern ideas about race, in the Western world, have their foundations in histories of European imperialism and colonialism. European settlers came into (often violent) contact with communities that they deemed different in appearance and customs. Missionaries, slavers, and explorers commonly described darker-skinned “others” as uncivilized, barbaric, and otherwise culturally deficient in comparison to their European compatriots. The oppression of darker-skinned groups was often based on the assumed superiority of European language, intelligence, morality, beauty, and culture. Competitive pursuit of wealth among European nations accelerated the exploitation, enslavement, and genocide of non-European peoples across the globe (Guthrie, 2004). This process of deeming one’s own group as superior and another group as inferior to motivate and justify violence and colonization is not unique to European contexts, but its duration, extent, and lasting implications make it one of the most staggering examples.

Third, there are instances where the historical legacy of racism continues to bear racist consequences today. Even when laws may have changed, traces of historical racism still remain. For example, the patterns of racially segregated housing in most major US cities that we see today map onto governmental policies that emerged in the 1910s and 20s to restrict where African Americans could live and buy homes (Rothstein, 2017). In South Africa, Apartheid (1940s-1990s) systematically denied non-White people access to most forms of capital, guaranteeing that South Africa would be controlled politically, socially, and economically by the nation’s minority White population. Despite the repeal of Apartheid laws and subsequent democratic elections, South African society still struggles with race-based inequalities in wealth, education, and health (National Research Council Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life, 2004; WIDER & Oosthuizen, 2019).

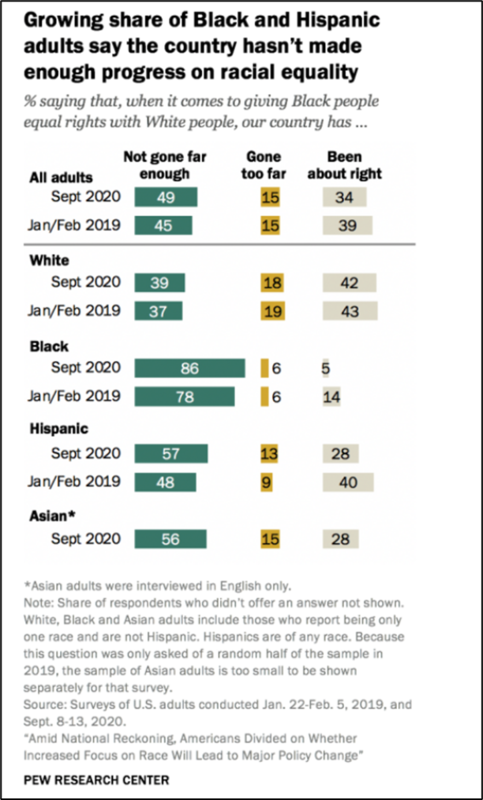

Bridging the Divide: Psychological Research on Perceiving and Denying Racism

We have noted that people see racism in different lights. How should we understand such differences in perception of racism? Which psychological factors predict perceptions or denial of racism? Before we discuss a few key factors, we want to point out a tendency of people to focus explanations on groups we think do not fit a perceived norm (Hegarty & Pratto, 2001). Take for example, the caption of Figure 3 from a Pew Research Center report (2020) on views of racial progress in the United States. The caption, “Growing share of Black and Hispanic adults say the country hasn’t made enough progress on racial equality” follows a common tendency to explain differences in views as if it is the minoritized group that deviates from an unspoken norm. Yes, when you examine the data, there are increases between 2019 and 2020 in the number of Black and Hispanic adults who say the United States has not gone far enough in giving equal rights to Black Americans. However, the data show that the graph could also be titled, ‘White views that America’s racial progress has been just about right, remain stagnant’. This tendency to locate the source of group differences in racial “otherness” is, itself, a manifestation of racism of a sort that Thomas Teo (2010) has referred to as epistemological violence.

To avoid this, social psychologists suggest that we “turn the analytic lens” (Adams & Salter, 2007) and consider the flip side of the same coin. In this case, we should consider the topic from the standpoint of marginalized groups. The statistic that requires further explanation is the widespread belief that U.S. society has already done enough to attain racial equality. Claims about equality are not consistent with statistical evidence, which documents racial inequalities in education, employment, health, and income (e.g., American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Educational Disparities, 2012; U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2016). Instead, beliefs about racial equality reflect psychological processes that can facilitate underreporting of the extent of racism in US society. So, what are those psychological processes? Research has revealed two mechanisms through which under-reporting and denial of systemic racism tend to occur. The first—called “defensive motivations” — focuses on how acknowledging racism or other forms of oppression can pose a threat to one’s identity or worldview. The second—known as “foundations of knowledge”—focuses on the cultural information that forms people’s judgments.

Defensive Motivations

For an advantaged person to admit that racism is prominent in one’s society, they must acknowledge that, ultimately, they receive advantages from an illegitimate system (Jost, Banaji & Nosek, 2004; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). This acknowledgment can threaten one’s sense of personal self-worth or the worth of the group to which the person belongs, known as collective self-worth (O’Brien & Major, 2005). When one’s group is implicated by historical or contemporary wrong-doing, members of that group are motivated to deny that wrong-doing is ongoing, significant, or pervasive in order to maintain a positive view of one’s social group (e.g., Branscombe et al., 1999). For example, when researchers boosted White research participants’ sense of self-worth with positive self-statements, they were then more likely to perceive systemic racism than did participants in a control condition (Unzueta & Lowery, 2008; Adams, Tormala, & O’Brien, 2006). Outside of the U.S. context, researchers have also found that, after completing a self-affirmation task, Israeli participants were more willing to acknowledge the victimization of Palestinians and the Israeli participation in that victimization (Čehajić-Clancy et al., 2011).

Opposition to acknowledging the extent to which racism operates in society can sometimes take the form of neutral claims on racism-relevant issues. For example, color-blind race ideology—the idea that people “do not see race”—can seem enlightened but, in practice, primarily serves the purpose of not “seeing” racism. Color-blind racial frames downplay the significance of ethnic and racial identity in peoples’ lived experiences and ignore the role of systemic oppression in impacting opportunities (e.g., Neville et al., 2013). Augoustinos and colleagues (2005) found that White Australians often used this principle to justify their opposition to anti-racism initiatives that would benefit Aboriginal people (Augoustinos, Tuffin, & Every, 2005; see also Tuffin, 2008). Notably, they would dismiss the need for race-conscious policies that would address historical discrimination by suggesting that all people should be treated equally (and so Aboriginal people should not be given something “extra”), that people should be treated as individuals (and so Aboriginal people should not be treated as a group), and that White people have advanced through merit (thereby ignoring historically accumulated advantages).

Foundations of Knowledge

Beyond defensive motivations, there is another category of explanations for the tendency to minimize or deny racism. This category concerns the cultural knowledge that informs people’s judgments. A person’s cultural frame might lead to various conclusions about racism. Imagine, for example, an officer deciding to detain a person at the U.S.-Mexico border. Using a “racism as individual prejudice” framework, one might look toward features of the officer (i.e., how they feel about Mexicans) and conclude that without evidence of personal racial bias, the detention was simply the case of an officer applying the law in race-neutral fashion. In contrast, using a more systemic definition of racism, one might see the resulting detention as racially biased, regardless of the personal inclinations of an individual officer, because of the unequal and disparate impact of the policy itself. Consistent with this, researchers have found endorsements for harsher treatment of undocumented Mexican immigrants than undocumented Canadian immigrants, especially among White participants who equated being a true American with ethnocentric cultural values (e.g., being able to speak English without a “foreign” accent) (Mukherjee et al., 2013). Discretionary institutional policies that rely on ethno-racial profiling and mistreatment are forms of structural racism and everyday violence (Alexander, 2011).

Another kind of cultural knowledge that facilitates or inhibits awareness of racism is collective memory about the role of past racism. Research on the Marley Hypothesis reveals that perceptions of racism are positively related to accurate historical knowledge (Bonam et al., 2019; Nelson, Adams, & Salter, 2013). In these studies, Black and White participants completed a “Black history” quiz that asked about historical events such as the U.S. government deliberately exposing black members of the military to syphilis, or hiding microphones in the hotel rooms of Civil Rights leaders. In the original study (Nelson et al., 2013) and in the replication (Bonam et al., 2019), White Americans scored lower on the measure of historical accuracy than did the Black Americans. Moreover, differences in knowledge of past racism helped explain Black and White differences in perception of present racism in U.S. society. Kurtiş and colleagues (2017) applied a similar research approach in Turkish contexts to further understand the relationship between critical historical knowledge about minority populations and policy support. They found that participants who demonstrated more accurate knowledge about officially silenced incidents of historical violence regarding minorities expressed greater support for protection of minority rights (Kurtiş, Soylu-Yalçınkaya, & Adams, 2017).

Collective memory about racism is not only an individual-level phenomenon. What we know about historical events is embodied in cultural tools like textbooks, school curricula, government-sanctioned holidays, and memorials. Official government accounts of history tend to sanitize or silence the more negative or racist stories in order to maintain a positive view of a country’s past and present. For example, Moore (2020) analyzed Australian history textbooks from 1950-2010. She was interested in the idea of interest-convergence. Interest convergence suggests that White (or dominant group) engagement in racial progress emerges when it aligns with their own interests. Moore (2020) discovered that earlier textbooks were ‘loud and proud’ when highlighting supposed deficiencies in Aboriginal people and White exceptionalism. However, over time they were reframed in more subtle terms. For example, early Aboriginal sea voyages are sometimes dismissed as short, easy, and as employing primitive boats. Similarly, descriptions of hunting and gathering are framed to suggest that Aboriginal communities operated by survival instinct rather than making sophisticated, intentional, and cooperative community decisions. These explanations of Aboriginal culture are less overtly racist, but continue to set up the idea that White settlers in Australia brought more sophisticated technology, the rule of law, and other forms of “civilization.” Moore (2020) suggests that changes from overtly racist textbook narratives to more subtle forms are designed to affirm White racial progressiveness while still upholding White Supremacy.

Consistent with these findings, research on how high schools in the U.S. discuss Black history revealed differences between predominantly Black and predominantly White schools (Salter & Adams, 2016). The researchers observed that predominantly White schools were more likely to present a version of Black history that promotes multicultural tolerance and diversity. Another notable strategy was to highlight individual Black American achievement—inventors, intellectuals, and Civil Rights heroes—while minimizing discussion of the historical barriers that these people faced. By contrast, predominantly Black schools were more likely to position Black history as accounts of the ongoing legacy of systemic exploitation and violent oppression. Cultural products, such as school curricula and textbooks, are not necessarily neutral accounts of what factually happened in the past; they reflect biases carried forward from the past and biases cultivated in the present.

Psychological studies have also highlighted the consequences of being exposed to different foundations of knowledge. In the same line of research described above, Salter and Adams (2016) randomly assigned White American university students to view two distinct representations of Black History Month: those from predominantly White schools or those from predominantly Black schools. Their results indicate that exposure to representations of history from predominantly Black schools (which were more likely to contain narratives of historical racism) led to greater perceptions of racism and support for antiracist policies. Similarly, in a study by Bonam and colleagues (2019), White American participants listened to a clip of historian Richard Rothstein on NPR’s Fresh Air program discussing the federal government’s role in creating Black ghettos and the ongoing legacy of systemic racism in housing. The researchers found that listening to the clip increased critical history knowledge (in comparison to a control condition), increased beliefs about the government’s active role in creating Black ghettos, and, in turn, increased perceptions of systemic racism.

Together, studies in this research program suggest how cultural representations of the past—what we might refer to as collective memory—matter for interpretation of the present. These studies also illuminate different sources of knowledge as important components for perceiving systemic racism. People who engage with representations of history that obscure past racism not only indicate a smaller role for racism as an explanation for contemporary events, but also express less support for reparative policies such as affirmative action than do people who engage with representations that acknowledge past racism.

Before we move to the final section of the module, we would like you to pause and consider the links between the two mechanisms described in this section: motivation to view one’s self positively and information-based judgments of racism. Though we have presented them separately, they are related to each other. For example, Mukherjee and colleagues (2017) asked participants in India to rate historical events that either glorified India or acknowledged wrongdoing against marginalized groups. The nation-glorifying events were rated as more relevant and more important for the study of Indian history. Notably, exposure to glorifying themes about collective achievements in India produced higher national identification and exposure to critical narratives about collective wrongdoing decreased national identification. Thus, the two processes affect one another: certain information boosted the desire to view one’s group favorably and viewing one’s group favorably predicted the types of information a person prefers. Important to our discussion, exposure to critical narratives produced greater perceptions of injustice in India. By contrast, exposure to themes that glorified India lowered perceptions of injustice. Regardless of individual beliefs and biases, mainstream cultural tools influence people to approach the topic of racial justice in ways that serve national and dominant group interests.

Implications for Action against Racism

A major goal of this module has been to articulate a systemic approach to understanding racism. We end the module by discussing the implications of this approach for action against racism. We break our discussion into three distinct sections: 1) anti-racist research, 2) anti-racist practices and interventions, and 3) intersectional considerations.

Anti-Racist Research

As discussed above, standard psychological accounts of racism often suggest that it is a problem of biased individuals. This individualistic approach to racism is evident in research on the topic. Racism research often examines individual personality traits such as authoritarian personality or social justice orientation (see Noba’s Prejudice, Discrimination, and Stereotyping). This approach to understanding racism leads to the idea that counteracting racism consists of measuring and altering personal qualities such as prejudice. As an example, one trend has involved the development of measures to identify people with implicit racist dispositions (e.g., Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). Another research trend has been to develop strategies that people might use to change their racist dispositions (Devine, Brodish, & Vance, 2005; Monteith, Ashburn-Nardo, Voils, & Czopp, 2002; Sassenberg & Moskowitz, 2005). Although research on individual factors in racism can reveal important insights, it may miss others.

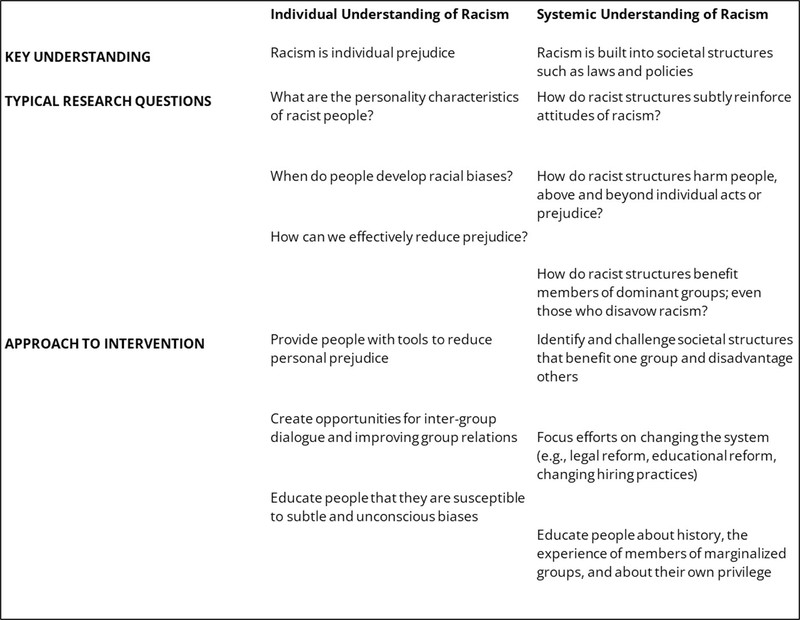

In contrast to an exclusive focus on individual dispositions, a systemic approach locates the roots of racism in social and cultural factors. This approach calls for research to examine the role that institutions, norms, laws, and policies play in racism. Table 1 lists examples of both individual and systemic questions about racism that researchers might ask. The systemic questions emphasize an attention to the interplay between individual and systemic oppression (see Fiske, Kitayama, Markus, & Nisbett, 1998; Oakes, Haslam, & Turner, 1994). Addressing these questions requires the use of unique theoretical perspectives and empirical techniques that are relatively rare in psychological research (e.g., discourse analysis, decolonial approaches, critical race theory frameworks). These approaches have the potential to yield new insights because they are more likely to include the experiences and perspectives of racially marginalized people.

Anti-Racist Intervention

Beyond its implications for research, a systemic approach to racism also suggests a shift in the emphasis of anti-racist interventions. Psychologists have typically framed the fight against racism as reducing individual prejudice or changing racist attitudes, and have designed effective programs to address this goal. Standard approaches to prejudice reduction seem to imply that the formerly racist individual, equipped with new attitudes, will now be anti-racist. In addition, this strategy implies that racially marginalized groups should accept a reduction of prejudice as a substitute for challenging the legacy of historical violence and the enduring, unjust status quo.

A systemic approach to anti-racism, by contrast, proposes to change the societal structures that foster racist tendencies (Karpinski & Hilton, 2001). This direction suggests that people might better control automatic racist tendencies by disengaging from experiences that promote racism and, instead, cultivate experiences that reinforce anti-racist tendencies. For example, interventions that increase engagement with diversity may lead participants to seek out diverse social communities or conversations that can promote non-racist attitudes (see Gurin et al., 2008).

The systemic approach to addressing racism also calls for dismantling racist structures that continue to cause harm, above and beyond the prejudices of any individual person. This includes challenging popular accounts of history; namely, progress narratives that promote the idea that society was once racist but now has overcome racism (Richeson, 2020). Such challenges emphasize:

- understanding the experiences of people who belong to historically marginalized groups

- exposing and reforming racist laws and institutional policies

- including alternative narratives of history that include the voices and understandings of marginalized communities

- raising awareness of privilege among members of dominant groups

One example of work in this direction involves challenging traditional notions of merit (Croizet, 2008). Specifically, intelligence tests, college entrance exams, and other assessments of “ability” or “aptitude” have been used to discriminate against people of color. Although these types of tests often yield differences in scores between members of various racial groups, these differences do not suggest that members of dominant groups are smarter or have more potential. Instead, they reflect inequalities in test familiarity, test preparation and support, educational support, and similar factors. Other examples of challenging common attitudes involve challenging conceptions of fairness (Jones, 1998; Smith & Crosby, 2008), national identity (Gurin et al., 2008), and accounts of history (Sears, 2008; Yellow Bird, 2004).

Intersectional Considerations

One of the complicating factors in successfully addressing racism is intersectionality. Rooted in Black feminist scholarship and critical race theory, intersectionality is the idea that people’s lived experience of oppression is based on more than a single identity. Intersectional analyses consider the oppression that arises out of the combination of various forms of discrimination which produces something distinctive from any one form of discrimination alone. One of the earliest recorded accounts of intersectionality dates back to the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio where a former slave, –Sojourner Truth– delivered her famous “Ain’t I a woman?” speech. In it, she provided an account of Black women born into slavery at the intersections of race and gender. In the 1990s, Kimberlé Crenshaw popularized the term intersectionality to describe the exclusion of Black women from feminist discourse (which equated women with White) and conversations about racism (which equated Black with men). Intersectionality situates experience within a complex web of power relations including dimensions such as race, gender, ethnicity, nationality, class, dis/ability, and sexuality (Anthias & Yuval-Davis, 1983; Crenshaw, 1989; Collins & Bilge, 2020 ; hooks, 2000; Hurtado, 1998). Attention to intersectionality can help us move beyond dichotomous formulations (e.g. us–them, oppressor–oppressed) to better appreciate the personal and cultural experiences that structure our everyday lives in distinct yet interrelated ways (Grewal & Kaplan, 2001). Intersectional analyses elevate the often-ignored experiences of people in marginalized identity positions (Matsuda, 1987). Accordingly, a primary contribution of intersectional analyses is to rethink standard accounts of knowledge (Kurtiş & Adams, 2016) and reimagine society from the perspective of those in marginalized positions.

Conclusion

Psychology has played a pivotal role in the struggle against racism since decades. Scholars have produced nuanced accounts about the dynamics of individual prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. Yet, persisting inequalities and racism reveal that efforts at research, intervention, and education remain incomplete. In this module, we have proposed that one direction for action is a systemic approach to racism. From this perspective, racism is not an issue of biased individuals, but instead, a historically rooted and enduring cultural pattern embedded in everyday laws, policies, and social attitudes that can cause harm for people from oppressed groups. Racism can also create advantages for people from dominant groups, even if they are unaware of these benefits or have no personal intention to discriminate. Accordingly, anti-racist efforts require greater attention to multiple and intersecting systems of oppression. These efforts compel us to pay attention to both how environmental patterns of racism shape individual experience, but also processes by which even good-intentioned individuals can unknowingly reproduce systems of racism.

Test your Understanding

Vocabulary

- Automatic

- Automatic biases are unintended, immediate, and irresistible.

- Aversive racism

- Aversive racism is unexamined racial bias that the person does not intend and would reject, but that avoids inter-racial contact.

- Blatant biases

- Blatant biases are conscious beliefs, feelings, and behavior that people are perfectly willing to admit, are mostly hostile, and openly favor their own group.

- Discrimination

- Discrimination is behavior that advantages or disadvantages people merely based on their group membership.

- Implicit Association Test

- Implicit Association Test (IAT) measures relatively automatic biases that favor own group relative to other groups.

- Model minority

- A minority group whose members are perceived as achieving a higher degree of socioeconomic success than the population average.

- Prejudice

- Prejudice is an evaluation or emotion toward people merely based on their group membership.

- Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) focuses on value conflicts but endorses respect for obedience and authority in the service of group conformity.

- Self-categorization theory

- Self-categorization theory develops social identity theory’s point that people categorize themselves, along with each other into groups, favoring their own group.

- Social dominance orientation (SDO) describes a belief that group hierarchies are inevitable in all societies and even good, to maintain order and stability.

- Social identity theory notes that people categorize each other into groups, favoring their own group.

- Stereotype Content Model

- Stereotype Content Model shows that social groups are viewed according to their perceived warmth and competence.

- Stereotypes

- Stereotype is a belief that characterizes people based merely on their group membership.

- Subtle biases

- Subtle biases are automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent, but real in their consequences.

References

- Adams, G., & Salter, P. S. (2007). Health psychology in African settings: A cultural-psychological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), 539-551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307076240

- Adams, G., Biernat, M., Branscombe, N. R., Crandall, C. S., & Wrightsman, L. S. (2008a). Beyond prejudice: Toward a sociocultural psychology of racism and oppression. In G. Adams, M. Biernat, N. R. Branscombe, C. S. Crandall, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Commemorating Brown: The social psychology of racism and discrimination (pp. 215–246). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11681-012

- Adams, G., Edkins, V., Lacka, D., Pickett, K., & Cheryan, S. (2008b). Teaching about racism: Pernicious implications of the standard portrayal. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30, 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530802502309

- Adams, G., Tormala, T. T., & O’Brien, L. T. (2006). The effect of self-affirmation on perception of racism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5), 616-626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.11.001

- Alexander, M. (2011). The New Jim Crow. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 9(1), 7-26.

- American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Educational Disparities. (2012). Ethnic and racial disparities in education: Psychology’s contributions to understanding and reducing disparities. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ed/resources/racial-disparities.aspx

- Anthias, F., & Yuval-Davis, N. (1983). Contextualizing feminism—gender, ethnic and class divisions. Feminist Review, 15(1), 62-75. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.1983.33

- Augoustinos, M., Tuffin, K., & Every, D. (2005). New racism, meritocracy and individualism: Constraining affirmative action in education. Discourse & Society, 16, 315–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926505051168

- Blauner, B. (2019). Talking past each other: Black and white languages of race. In F. L. Pincus & H. J. Ehrlich (Eds.), Race and ethnic conflict: Contending views on prejudice, discrimination, and ethnoviolence (pp. 30-40). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429497896

- Bonam, C. M., Nair Das, V., Coleman, B. R., & Salter, P. (2019). Ignoring history, denying racism: Mounting evidence for the Marley hypothesis and epistemologies of ignorance. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(2), 257-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/194855061775158

- Branscombe, N. R., Ellemers, N., Spears, R. & Doosje, B. (1999). The context and content of social identity threat. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp.35–58). Blackwell Science.

- Carter, E. R., & Murphy, M. C. (2015). Group‐based differences in perceptions of racism: What counts, to whom, and why?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 269-280. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12181

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality. John Wiley & Sons.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989/1993). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In D. K. Weisbert (Ed.), Feminist legal theory: Foundations (pp. 383–395). Temple University Press.

- Croizet, J.-C. (2008). The pernicious relationship between merit assessment and discrimination in education. In G. Adams, M. Biernat, N. R. Branscombe, C. S. Crandall, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Commemorating Brown: The social psychology of racism and discrimination (pp. 153–172). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11681-009

- Devine, P. G., Brodish, A. B., & Vance, S. L. (2005). Self-regulatory processes in interracial interactions: The role of internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. In J. P. Forgas, K. D. Williams,& S. M. Laham (Eds.), Social motivation: Conscious and unconscious processes (pp. 249 –273). Psychology Press.

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). Aversive racism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 36, pp. 1–52). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(04)36001-6

- Fiske, A. P., Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., & Nisbett, R. E. (1998). The cultural matrix of social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 915–981). McGraw-Hill.

- Garner, S. (2007). Whiteness : An Introduction. Routledge.

- Grewal, I., & Kaplan, C. (2001). Global identities: Theorizing transnational studies of sexuality. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 7, 663-679. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-7-4-663

- Gurin, P., Gurin, G., Matlock, J., & Wade-Golden, K. (2008). Sense of commonality in values among racial-ethnic groups: An opportunity for a new conception of integration. In G. Adams, M. Biernat, N. R. Branscombe, C. S. Crandall, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Commemorating Brown: The social psychology of racism and discrimination (pp. 115–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11681-007

- Guthrie, R. V. (2004). Even the rat was white: A historical view of psychology (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hauser, C. (2020, June). Merriam-Webster Revises ‘Racism’ Entry After Missouri Woman Asks for Changes. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/10/us/merriam-webster-racism-definition.html

- Hegarty, P., & Pratto, F. (2001). The effects of social category norms and stereotypes on explanations for intergroup differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(5), 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.723

- Hurtado, A. (1998). Sitios y lenguas: Chicanas theorize feminisms. Hypatia, 13, 134-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01230.x

- Ignatiev, N. (2012). How the Irish became white. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203473009

- Jones, J. M. (1998). Psychological knowledge and the new American dilemma of race. Journal of Social Issues, 54(4), 641-662. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01241.x

- Jones, J. M. (1997). Prejudice and racism. McGraw-Hill Humanities, Social Sciences & World Languages.

- Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25(6), 881-919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x

- Karpinski, A., & Hilton, J. L. (2001). Attitudes and the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.774

- Kurtiş, T., & Adams, G. (2016). Decolonial intersectionality: Implications for theory, research, and pedagogy. In K. Case (Ed.) Intersectional pedagogy (pp. 46-60). Routledge.

- Kurtiş T., Soylu Yalçınkaya, N., & Adams, G. (2017). Silence in official representations of Turkish history: Implications for national identity and minority rights. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 5(2), 608–629. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v5i2.714

- Matsuda, M. (1987). Looking to the bottom: Critical legal studies and reparations. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 22, 323-399.

- Monteith, M. J., Ashburn-Nardo, L., Voils, C. I., & Czopp, A. M. (2002). Putting the brakes on prejudice: On the development and operation of cues for control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1029–1050. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1029

- Moore, R. (2020). Whiteness=politeness: interest-convergence in Australian history textbooks, 1950–2010, Critical Discourse Studies, 17(1), 111-129. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2019.1637760

- Mukherjee, S., Adams, G., & Molina, L. E. (2017). A cultural-psychological analysis of collective memory as mediated action: Constructions of Indian history. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 5(2), 558– 587. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v5i2.705

- Mukherjee, S., Molina, L. E., & Adams, G. (2013). “Reasonable suspicion” about tough immigration legislation: Enforcing laws or ethnocentric exclusion? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(3), 320–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032944

- National Human Genome Research Institute (2018). Genetics vs. Genomics Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Genetics-vs-Genomics.

- National Research Council Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life (2004). An Exploratory Investigation into Racial Disparities in the Health of Older South Africans. In N.B. Anderson, R.A. Bulatao, B. Cohen (Eds) Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK25536/

- Nelson, J. C., Adams, G., & Salter, P. S. (2013). The Marley hypothesis: Denial of racism reflects ignorance of history. Psychological Science, 24, 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612451466

- Neville, H. A., Awad, G. H., Brooks, J. E., Flores, M. P., & Bluemel, J. (2013). Color-blind racial ideology: Theory, training, and measurement implications in psychology. American Psychologist, 68(6), 455-466. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033282

- Oakes, P. J., Haslam, S. A., & Turner, J. C. (1994). Stereotyping and social reality. Blackwell Publishing.

- O’Brien, L. T., & Major, B. (2005). System-justifying beliefs and psychological well-being: The roles of group status and identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(12), 1718-1729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205278261

- Pew Research Center (2020, October 6). Amid national reckoning, Americans divided on whether increased focus on race will lead to major policy change. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/10/06/amid-national-reckoning-americans-divided-on-whether-increased-focus-on-race-will-lead-to-major-policy-change/

- Pew Research Center (2016, June 27). On views of race and inequality, Blacks and Whites Are worlds apart. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2016/06/27/on-views-of-race-and-inequality-blacks-and-whites-are-worlds-apart/

- Richeson, J. (2020, July 27). Americans Are Determined to Believe in Black Progress. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/the-mythology-of-racial-progress/614173/

- Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing.

- Salter, P. S., & Adams, G. (2016). On the intentionality of cultural products: Representations of Black history as psychological affordances. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 1166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01166

- Salter, P. S., Adams, G., & Perez, M. J. (2018). Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: A cultural-psychological perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(3), 150-155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417724239

- Sassenberg, K., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2005). Don’t stereotype, think different! Overcoming automatic stereotype activation by mindset priming. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(5), 506-514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2004.10.002

- Sears, D. O. (2008). The American color line 50 years after Brown v. Board: Many \”peoples of color\” or Black exceptionalism? In G. Adams, M. Biernat, N. R. Branscombe, C. S. Crandall, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Commemorating Brown: The social psychology of racism and discrimination (pp. 133–152). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11681-008

- Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175043

- Smith, A. E., & Crosby, F. J. (2008). From Kansas to Michigan: The path from desegregation to diversity. In G. Adams, M. Biernat, N. R. Branscombe, C. S. Crandall, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Commemorating Brown: The social psychology of racism and discrimination (pp. 99–113). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11681-006

- Sommers, S. R., & Norton, M. I. (2006). Lay theories about white racists: What constitutes racism (and what doesn’t). Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 9(1), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430206059881

- Tatum, B.D. (1997). “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?” and Other Conversations about Race. Basic Books.

- Teo, T. (2010). What is epistemological violence in the empirical social sciences?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 295-303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00265.x

- Tuffin, K. (2008). Racist discourse in New Zealand and Australia: Reviewing the last 20 years. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 591-607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00071.x

- U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. (2016). Health, United States, 2015: With special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf

- Unzueta, M. M., & Lowery, B. S. (2008). Defining racism safely: The role of self-image maintenance on white Americans’ conceptions of racism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(6), 1491-1497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.011

- WIDER, U.N.U. & Oosthuizen, M. (2019). Racial inequality and demographic change in South Africa: Impacts on economic development. Research Brief 2019/5. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. Retrieved from https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/racial-inequality-and-demographic-change-south-africa

- Wellman, D.T. (1993). Portraits of White Racism, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press.

- Yellow Bird, M. (2004). Cowboys and Indians: Toys of genocide, icons of American colonialism. Wicazo Sa Review, 19(2), 33-48.

- hooks, b. (2000). Feminist theory: From margin to center. Pluto Press.

- Čehajić-Clancy, S., Effron, D. A., Halperin, E., Liberman, V., & Ross, L. D. (2011). Affirmation, acknowledgment of in-group responsibility, group-based guilt, and support for reparative measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023936

A political system with policies that promote segregation of the basis of race. The word means “apartness” in Afrikaans, and the system was in use in South Africa from the 1950s through the 1990s.

A system of advantage and disadvantage based on social, historical, and cultural constructions of race and ethnicity (Jones, 1997/1998; Tatum 1997; Wellman 1993).

An evaluation or emotion toward people based merely on their group membership.

A mental process of using information shortcuts about a group to effectively navigate social

situations or make decisions.

Discrimination is behavior that advantages or disadvantages people merely based on their group membership.

An unreasonable opinion or prejudice against a category of people.

Approaches to understanding racism that emphasize the roles that societal factors—historical, cultural, legal, political, and economic—have played in organizing who is at the top or bottom of a society’s racial hierarchy.

Something that is not found in objective reality but it, instead, the result of a common shared understanding. Social constructs are defined and given meaning by a particular society.

Observable traits, such as hair or eye color, that are result of genetic and environmental interactions.

To treat a person or group as socially inferior, peripheral, or unimportant.

A form of scientific or academic racism in which observers interpret empirical data in ways that problematize or suggest the inferiority of racial and cultural Others, even when the data allow for equally viable alternative interpretations (Teo, 2010).

The idea that a person's self-worth is influenced by the treatment of and perceptions about a group to which that person belongs.

A belief that racism is a past-- rather than a current-- phenomenon. Also, the idea that the best way to eliminate discrimination is to ignore categorical differences between people and their experiences.

Knowledge that is shared among members of a group about the historical experiences of that group.

These lines from “Buffalo Soldier” by Bob Marley and the Wailers provide a brief statement of the Marley Hypothesis: the suggestion that White denial of racism reflects a collectively cultivated ignorance of the role that racism has played in U.S. society throughout its history.

The tendency for White (or dominant group) engagement in racial progress to emerge when it aligns with the interests of the dominant group.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a critical framework that emerged as an intervention in the 1970s to explain how racism and other tools of oppression shape law and society. Building on the pioneering work of activists and legal scholars like Derrick Bell, Kimberle Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, and Mari Matsuda, CRT has influenced social scientists in fields outside of legal studies including education, sociology, public health, and psychology. The framework provides a foundation for understanding racism as systemic, the ideologies that reinforce and maintain racist structures, and the value of perspectives and theories grounded in the experiences of oppressed and marginalized peoples. For an introduction to CRT, we recommend Delgado & Stefancic, 2012. To learn more about the intersections of psychology and CRT see Jones, 1998; Adams & Salter, 2011, and Salter & Adams, 2013.

The idea that social identities can overlap. For instance, a person could be "Canadian", "Indigenous" and "a woman".