6 Biogeochemical Cycles

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the concept of net primary productivity

- Explain the reasons why different biomes have different levels of primary productivity

- Discuss the biogeochemical cycles of water, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus

- Explain how human activities have impacted these cycles and the resulting potential consequences for Earth

Net Primary Productivity

Autotrophs, such as plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria, are the energy source for a majority of the world’s ecosystems. These ecosystems are often described by grazing and detrital food webs. Photoautotrophs harness the Sun’s solar energy by converting it to chemical energy in the form of ATP (and NADP). The energy stored in ATP is used to synthesize complex organic molecules, such as glucose. The rate at which photosynthetic producers incorporate energy from the Sun is called gross primary productivity. However, not all of the energy incorporated by producers is available to the other organisms in the food web because producers must also grow and reproduce, which consumes energy. Net primary productivity (NPP) is the energy that remains in the producers after accounting for these organisms’ respiration and heat loss. The net primary productivity is then available to the primary consumers at the next trophic level. Net primary productivity is often measured by calculating the biomass of the organisms in an area, which is the dry weight of all the organic matter in an organism. Dry weight is used because the water stored in the cells of an organism can vary greatly depending on environmental conditions.

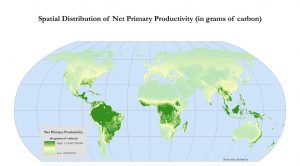

Net primary productivity varies greatly across biomes, as seen in Figure 1. Estuaries, or regions where rivers meet the ocean, have the highest NPP on Earth. This is largely because rivers carry a constant supply of nutrients from upstream and deposit them into the ocean, providing support for a large diversity of plants, animals, and other organisms. On land, the most productive biomes are swamps and tropical rain forests. This is because these areas have high amounts of available moisture and high temperatures. Plants in warm, moist biomes have a longer growing season and rarely lack water. Moderate amounts of NPP are found in grasslands and temperate forests, or forests with an intermediate temperature and precipitation, such as the hardwood forests of North America. Terrestrial biomes with the lowest NPP are deserts and tundra. Tundras are treeless arctic biomes in which the subsoil is permanently frozen as permafrost. Lack of water in deserts and cold temperatures in tundras severely limit the ability of plants to thrive.

Knowledge Check

Biogeochemical Cycles

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for chemoautotrophs) and leaving as heat during the transfers between trophic levels. Rather than flowing through an ecosystem, the matter that makes up living organisms is conserved and recycled. The five most common elements associated with organic molecules—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, and phosphorus—take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in the atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath Earth’s surface. Geologic processes, such as weathering, erosion, water drainage, and the subduction of the continental plates, all play a role in the cycling of elements on Earth. Because geology and chemistry have major roles in the study of this process, the recycling of inorganic matter between living organisms and their nonliving environment is called a biogeochemical cycle.

The chemicals moving through a biogeochemical cycle may be stored in one place for a few hours, a few days, a few years, or even millions of years. The places where these chemicals are stored are known as reservoirs, and the amount of time spent in each reservoir is known as residence time. The processes that move chemicals from one reservoir to another are known as fluxes or flux mechanisms. For example, water may be stored in the ocean reservoir and move to the atmosphere reservoir through the flux mechanism of evaporation.

Water, which contains hydrogen and oxygen, is essential to all living processes. The hydrosphere is the area of Earth where water movement and storage occurs: as liquid water on the surface (rivers, lakes, oceans) and beneath the surface (groundwater) or ice, (polar ice caps and glaciers), and as water vapor in the atmosphere. Carbon is found in all organic macromolecules and is an important constituent of fossil fuels. Nitrogen is a major component of our nucleic acids and proteins and is critical to human agriculture. Phosphorus, a major component of nucleic acids, is one of the main ingredients (along with nitrogen) in artificial fertilizers used in agriculture, which has environmental impacts on our surface water.

The cycling of these elements is interconnected. For example, the movement of water is critical for the leaching of nitrogen and phosphate into rivers, lakes, and oceans. The ocean is also a major reservoir for carbon. Thus, mineral nutrients are cycled, either rapidly or slowly, through the entire biosphere between the biotic and abiotic world and from one living organism to another.

The Water Cycle

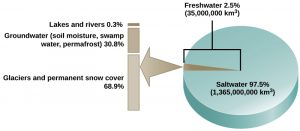

Water is essential for all living processes. The human body is more than one-half water and human cells are more than 70 percent water. Thus, most land animals need a supply of fresh water to survive. Of the stores of water on Earth, 97.5 percent is salt water (Figure 2). Of the remaining water, 99 percent is locked as underground water or ice. Thus, less than one percent of fresh water is present in lakes and rivers. Many living things are dependent on this small amount of surface fresh water supply, a lack of which can have important effects on ecosystem dynamics. Humans, of course, have developed technologies to increase water availability, such as digging wells to harvest groundwater, storing rainwater, and using desalination to obtain drinkable water from the ocean. Although this pursuit of drinkable water has been ongoing throughout human history, the supply of fresh water continues to be a major issue in modern times.

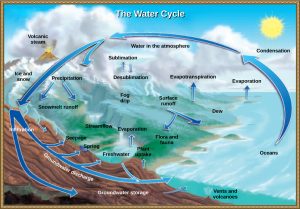

The various processes that occur during the cycling of water are illustrated in Figure 3. The processes include the following:

- evaporation and sublimation

- condensation and precipitation

- subsurface water flow

- surface runoff and snowmelt

- streamflow

The water cycle (also known as the hydrologic cycle) is driven by the Sun’s energy as it warms the oceans and other surface waters. This leads to evaporation (water to water vapor) of liquid surface water and sublimation (ice to water vapor) of frozen water, thus moving large amounts of water into the atmosphere as water vapor. Over time, this water vapor condenses into clouds as liquid or frozen droplets and eventually leads to precipitation (rain or snow), which returns water to Earth’s surface. Rain reaching Earth’s surface may evaporate again, flow over the surface, or percolate into the ground. Most easily observed is surface runoff: the flow of fresh water either from rain or melting ice. Runoff can make its way through streams and lakes to the oceans or flow directly to the oceans themselves.

In most natural terrestrial environments rain encounters vegetation before it reaches the soil surface. A significant percentage of water evaporates immediately from the surfaces of plants. What is left reaches the soil and begins to move down. Surface runoff will occur only if the soil becomes saturated with water in a heavy rainfall. Most water in the soil will be taken up by plant roots. The plant will use some of this water for its own metabolism, and some of that will find its way into animals that eat the plants, but much of it will be lost back to the atmosphere through a process known as evapotranspiration. Water enters the vascular system of the plant through the roots and evaporates, or transpires, through the stomata of the leaves. Water in the soil that is not taken up by a plant and that does not evaporate is able to percolate into the subsoil and bedrock. Here it forms groundwater.

Groundwater is a significant reservoir of fresh water. It exists in the pores between particles in sand and gravel, or in the fissures in rocks. Shallow groundwater flows slowly through these pores and fissures and eventually finds its way to a stream or lake where it becomes a part of the surface water again. Streams do not flow because they are replenished from rainwater directly; they flow because there is a constant inflow from groundwater below. Some groundwater is found very deep in the bedrock and can persist there for millennia. Most groundwater reservoirs, or aquifers, are the source of drinking or irrigation water drawn up through wells. In many cases these aquifers are being depleted faster than they are being replenished by water percolating down from above.

Rain and surface runoff are major ways in which minerals, including carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus are cycled from land to water. The environmental effects of runoff will be discussed later as these cycles are described.

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon is the fourth most abundant element in living organisms. Carbon is present in all organic molecules, and its role in the structure of macromolecules is of primary importance to living organisms. Carbon compounds contain energy, and many of these compounds from plants and algae have remained stored as fossilized carbon, which humans use as fuel. Since the 1800s, the use of fossil fuels has accelerated. As global demand for Earth’s limited fossil fuel supplies has risen since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the amount of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere has increased as the fuels are burned. Carbon dioxide is known as a greenhouse gas because it is a major contributor to global warming.

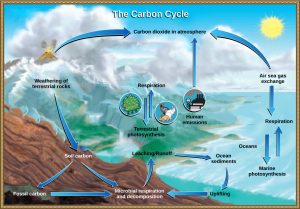

The carbon cycle is most easily studied as two interconnected subcycles: one dealing with rapid carbon exchange among living organisms and the other dealing with the long-term cycling of carbon through geologic processes. The entire carbon cycle is shown in Figure 4.

The Biological Carbon Cycle

Living organisms are connected in many ways, even between ecosystems. A good example of this connection is the exchange of carbon between heterotrophs and autotrophs within and between ecosystems by way of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is the basic building block that autotrophs use to build multi-carbon, high-energy sugar compounds during the process of photosynthesis. The energy harnessed from the Sun is used by these organisms to form the covalent bonds that link carbon atoms together. These chemical bonds store this energy for later use in the process of cellular respiration. Most terrestrial autotrophs obtain their carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere, while marine autotrophs acquire it in the dissolved form (carbonic acid, HCO3–). However the carbon dioxide is acquired, a byproduct of fixing carbon in organic compounds is oxygen. Photosynthetic organisms are responsible for maintaining approximately 21 percent of the oxygen content of the atmosphere that we observe today.

The partners in biological carbon exchange are the heterotrophs (especially the primary consumers, largely herbivores). Heterotrophs acquire the high-energy carbon compounds from the autotrophs by consuming them and breaking them down by cellular respiration to obtain cellular energy, such as ATP. The most efficient type of respiration, aerobic respiration, requires oxygen obtained from the atmosphere or dissolved in water. Thus, there is a constant exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the autotrophs (which need the carbon) and the heterotrophs (which need the oxygen). Autotrophs also respire and consume the organic molecules they form: using oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. They release more oxygen gas as a waste product of photosynthesis than they use for their own respiration; therefore, there is excess available for the respiration of other aerobic organisms. Gas exchange through the atmosphere and water is one way that the carbon cycle connects all living organisms on Earth.

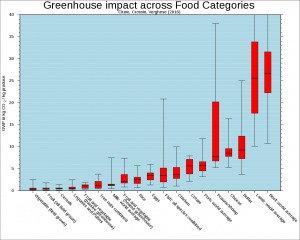

Carbon is also added to the atmosphere by the agriculture practices of humans. The large number of land animals raised to feed Earth’s growing human population results in increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, largely because more land is required to raise livestock animals than to raise plants (Figure 5). This leads to increased deforestation as trees are cut down to make room for farms. Cattle have an even greater impact on climate change than other animals raised for food because their unique digestive system also produces methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas that is at least 20 times stronger in its warming potential than carbon dioxide. Although much of the debate about the future effects of increasing atmospheric carbon on climate change focuses on fossils fuels, scientists are growing more concerned about the impacts of raising an ever growing number of animals for food. Scientists must also take natural processes, such as volcanoes, plant growth, soil carbon levels, and respiration, into account as they model and predict the future impact of human changes to the carbon cycle.

The Biogeochemical Carbon Cycle

The movement of carbon through land, water, and air is complex, and, in many cases, it occurs much more slowly geologically than the movement between living organisms. Carbon is stored for long periods in what are known as carbon reservoirs, which include the atmosphere, bodies of liquid water (mostly oceans), ocean sediment, soil, rocks (including fossil fuels), and Earth’s interior.

As stated, the atmosphere is a major reservoir of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide that is essential to the process of photosynthesis. The level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is greatly influenced by the reservoir of carbon in the oceans. The exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and water reservoirs influences how much carbon is found in each, and each one affects the other reciprocally. Carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere dissolves in water and, unlike oxygen and nitrogen gas, reacts with water molecules to form ionic compounds. Some of these ions combine with calcium ions in the seawater to form calcium carbonate (CaCO3), a major component of the shells of marine organisms. These organisms eventually form sediments on the ocean floor. Over geologic time, the calcium carbonate forms limestone, which comprises the largest carbon reservoir on Earth.

On land, carbon is stored in soil as organic carbon as a result of the decomposition of living organisms or from weathering of terrestrial rock and minerals. Deeper under the ground, at land and at sea, are fossil fuels, the anaerobically decomposed remains of plants that take millions of years to form. Fossil fuels are considered a non-renewable resource because their use far exceeds their rate of formation. A non-renewable resource is either regenerated very slowly or not at all. Another way for carbon to enter the atmosphere is from land (including land beneath the surface of the ocean) by the eruption of volcanoes and other geothermal systems. Carbon sediments from the ocean floor are taken deep within Earth by the process of subduction: the movement of one tectonic plate beneath another. Carbon is released as carbon dioxide when a volcano erupts or from volcanic hydrothermal vents.

Knowledge Check

The Nitrogen Cycle

Getting nitrogen into the living world is difficult. Plants and phytoplankton are not equipped to incorporate nitrogen from the atmosphere (which exists as tightly bonded, triple covalent N2) even though this molecule comprises approximately 78 percent of the atmosphere. Nitrogen enters the living world via free-living and symbiotic bacteria, which incorporate nitrogen into their cells through nitrogen fixation (conversion of N2). Cyanobacteria live in most aquatic ecosystems where sunlight is present; they play a key role in nitrogen fixation. Cyanobacteria are able to use inorganic sources of nitrogen to “fix” nitrogen. Rhizobium bacteria live symbiotically in the root nodules of legumes (such as peas, beans, and peanuts) and provide them with the organic nitrogen they need. Free-living bacteria, such as Azotobacter, are also important nitrogen fixers.

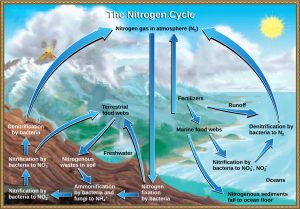

Organic nitrogen is especially important to the study of ecosystem dynamics since many ecosystem processes, such as primary production and decomposition, are limited by the available supply of nitrogen. As shown in Figure 6, the nitrogen that enters living systems by nitrogen fixation is eventually converted from organic nitrogen back into nitrogen gas by bacteria. This process occurs in three steps in terrestrial systems: ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. First, the ammonification process converts nitrogenous waste from living animals or from the remains of dead animals into ammonium (NH4+ ) by certain bacteria and fungi. Second, this ammonium is then converted to nitrites (NO2−) by nitrifying bacteria, such as Nitrosomonas, through nitrification. Subsequently, nitrites are converted to nitrates (NO3−) by similar organisms. Lastly, the process of denitrification occurs, whereby bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Clostridium, convert the nitrates into nitrogen gas, thus allowing it to re-enter the atmosphere.

Human activity can release nitrogen into the environment by two primary means: the combustion of fossil fuels, which releases various nitrogen oxides, and by the use of artificial fertilizers (which contain nitrogen and phosphorus compounds) in agriculture, which are then washed into lakes, streams, and rivers by surface runoff. Atmospheric nitrogen (other than N2) is associated with several effects on Earth’s ecosystems including the production of acid rain (as nitric acid, HNO3) and greenhouse gas effects (as nitrous oxide, N2O), potentially causing climate change. A major effect from fertilizer runoff is saltwater and freshwater eutrophication, a process whereby nutrient runoff causes the overgrowth of algae and a number of consequential problems.

A similar process occurs in the marine nitrogen cycle, where the ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification processes are performed by marine bacteria and archaea. Some of this nitrogen falls to the ocean floor as sediment, which can then be moved to land in geologic time by uplift of Earth’s surface, and thereby incorporated into terrestrial rock. Although the movement of nitrogen from rock directly into living systems has been traditionally seen as insignificant compared with nitrogen fixed from the atmosphere, a recent study showed that this process may indeed be significant and should be included in any study of the global nitrogen cycle.

The Phosphorus Cycle

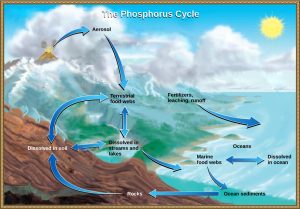

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for living processes; it is a major component of nucleic acids and phospholipids, and, as calcium phosphate, makes up the supportive components of our bones. Phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient (necessary for growth) in aquatic, particularly freshwater, ecosystems.

Phosphorus occurs in nature as the phosphate ion (PO43-), found largely in rocks. Humans extract this phosphate and use it in products such as fertilizer and detergents, which can run off into water bodies. In addition to phosphate runoff as a result of human activity, natural surface runoff occurs when it is leached from phosphate-containing rock by weathering, thus sending phosphates into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. This rock has its origins in the ocean. Phosphate-containing ocean sediments form primarily from the bodies of ocean organisms and from their excretions. However, volcanic ash, aerosols, and mineral dust may also be significant phosphate sources. This sediment then is moved to land over geologic time by the uplifting of Earth’s surface (Figure 7).

Phosphorus is also exchanged between phosphate dissolved in the ocean and marine organisms. The movement of phosphate from the ocean to the land and through the soil is extremely slow, with the average phosphate ion having an oceanic residence time between 20,000 and 100,000 years.

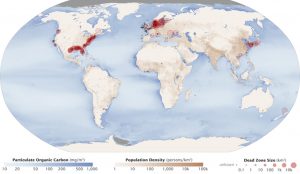

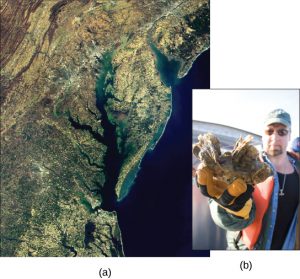

Excess phosphorus and nitrogen that enter these ecosystems from fertilizer runoff and from sewage cause excessive growth of algae. The subsequent death and decay of these organisms depletes dissolved oxygen, which leads to the death of aquatic organisms, such as shellfish and finfish. This process is responsible for dead zones in lakes and at the mouths of many major rivers and for massive fish kills, which often occur during the summer months (Figure 8).

A dead zone is an area in lakes and oceans near the mouths of rivers where large areas are periodically depleted of their normal flora and fauna; these zones can be caused by eutrophication, oil spills, dumping toxic chemicals, and other human activities. The number of dead zones has increased for several years, and more than 400 of these zones were present as of 2008. One of the worst dead zones is off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico: fertilizer runoff from the Mississippi River basin created a dead zone of over 8,463 square miles. Phosphate and nitrate runoff from fertilizers also negatively affect several lake and bay ecosystems including the Chesapeake Bay in the eastern United States.

Career Connection

The Chesapeake Bay (Figure 8a) is one of the most scenic areas on Earth; it is now in distress and is recognized as a case study of a declining ecosystem. In the 1970s, the Chesapeake Bay was one of the first aquatic ecosystems to have identified dead zones, which continue to kill many fish and bottom-dwelling species such as clams, oysters, and worms. Several species have declined in the Chesapeake Bay because surface water runoff contains excess nutrients from artificial fertilizer use on land. The source of the fertilizers (with high nitrogen and phosphate content) is not limited to agricultural practices. There are many nearby urban areas and more than 150 rivers and streams empty into the bay that are carrying fertilizer runoff from lawns and gardens. Thus, the decline of the Chesapeake Bay is a complex issue and requires the cooperation of industry, agriculture, and individual homeowners.

Of particular interest to conservationists is the oyster population (Figure 8b); it is estimated that more than 200,000 acres of oyster reefs existed in the bay in the 1700s, but that number has now declined to only 36,000 acres. Oyster harvesting was once a major industry for Chesapeake Bay, but it declined 88%between 1982 and 2007. This decline was caused not only by fertilizer runoff and dead zones, but also because of overharvesting. Oysters require a certain minimum population density because they must be in close proximity to reproduce. Human activity has altered the oyster population and locations, thus greatly disrupting the ecosystem.

The restoration of the oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay has been ongoing for several years with mixed success. Not only do many people find oysters good to eat, but the oysters also clean up the bay. They are filter feeders, and as they eat, they clean the water around them. Filter feeders eat by pumping a continuous stream of water over finely divided appendages (gills in the case of oysters) and capturing prokaryotes, plankton, and fine organic particles in their mucus. In the 1700s, it was estimated that it took only a few days for the oyster population to filter the entire volume of the bay. Today, with the changed water conditions, it is estimated that the present population would take nearly a year to do the same job.

The restoration goal is to find a way to increase population density so the oysters can reproduce more efficiently. Many disease-resistant varieties (developed at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science for the College of William and Mary) are now available and have been used in the construction of experimental oyster reefs. Efforts by Virginia and Delaware to clean and restore the bay have been hampered because much of the pollution entering the bay comes from other states, which emphasizes the need for interstate cooperation to gain successful restoration.

The new, hearty oyster strains have also spawned a new and economically viable industry—oyster aquaculture—which not only supplies oysters for food and profit, but also has the added benefit of cleaning the bay.

Knowledge Check

Summary

Biogeochemical cycles show how essential elements like water, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus move through living things and the environment. These elements cycle between the air, water, soil, and organisms, supporting life on Earth. Human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, cutting down forests, and using fertilizers, can disrupt these cycles. These disruptions lead to problems like climate change, pollution, and dead zones in water. Understanding these cycles helps us see how all parts of the planet are connected and why protecting natural processes is important for a healthy ecosystem.

Attribution

“Biogeochemical Cycles” in OpenStax Concepts of Biology, modified by Sean Whitcomb. License: CC BY

Media Attributions

- Spatial Distribution of Net Primary Productivity (in grams of ca © SEDACMaps adapted by Sean Whitcomb is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Water_distribution © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Water_cycle © John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Carbon_cycle © John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Food carbon © DeWikiMan is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Nitrogen_cycle © John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Phosphorus_cycle © John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dead zones world map © Robert Simmon, Jesse Allen, NASA Earth Observatory) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Chesapeake Bay oyster © NASA/MODIS; U.S. Army adapted by OpenStax is licensed under a Public Domain license