10 Evidence of Evolution

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain how the modern theory of evolution differs from previous views

- Describe how the present-day theory of evolution was developed

- Explain sources of evidence for evolution

- Define homologous and vestigial structures

- Identify common misconceptions about evolution

- Respond to common criticisms of evolution

Development of the Theory of Evolution

Evolution is a gradual change in the characteristics of a population over time, which can lead to the development of new species. There are several mechanisms by which populations evolve, which will be explored in detail in the next chapter. The current chapter will outline the development of the theory of evolution, present some of the major pieces of evidence supporting the theory of evolution, and it will address some of the common criticisms leveled against evolution.

The theory of evolution by natural selection describes a mechanism for species change over time. That species change had been suggested and debated well before Darwin. The view that species were static and unchanging was grounded in the writings of Plato and Aristotle, yet there were also ancient Greeks that expressed evolutionary ideas.

In the eighteenth century, ideas about the evolution of animals were reintroduced by the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon and even by Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. During this time, it was also accepted that there were extinct species. At the same time, James Hutton, the Scottish naturalist, proposed that geological change occurred gradually by the accumulation of small changes from processes (over long periods of time) just like those happening today. This contrasted with the predominant view that the geology of the planet was a consequence of catastrophic events occurring during a relatively brief past. Hutton’s view was later popularized by the geologist Charles Lyell in the nineteenth century. Lyell became a friend to Darwin and his ideas were very influential on Darwin’s thinking. Lyell argued that the greater age of Earth gave more time for gradual change in species, and the process provided an analogy for gradual change in species.

In the early nineteenth century, French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a book that detailed a possible mechanism for evolutionary change that is now referred to as inheritance of acquired characteristics. In Lamarck’s theory, modifications in an individual caused by its environment, or the use or disuse of a structure during its lifetime, could be inherited by its offspring and, thus, bring about change in a species. While this mechanism for evolutionary change as described by Lamarck was discredited, Lamarck’s ideas were an important influence on evolutionary thought. The inscription on the statue of Lamarck that stands at the gates of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris describes him as the “founder of the doctrine of evolution.”

Darwin, Wallace, and Natural Selection

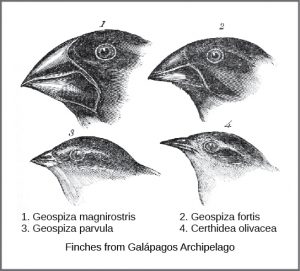

The actual mechanism for evolution was independently conceived of and described by two naturalists, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace, in the mid-nineteenth century. Importantly, each spent time exploring the natural world on expeditions to the tropics. From 1831 to 1836, Darwin traveled around the world on H.M.S. Beagle, visiting South America, Australia, and the southern tip of Africa. Wallace traveled to Brazil to collect insects in the Amazon rainforest from 1848 to 1852 and to the Malay Archipelago from 1854 to 1862. Darwin’s journey, like Wallace’s later journeys in the Malay Archipelago, included stops at several island chains, the last being the Galápagos Islands (west of Ecuador). On these islands, Darwin observed species of organisms on different islands that were clearly similar, yet had distinct differences. For example, the ground finches inhabiting the Galápagos Islands comprised several species that each had a unique beak shape (Figure 1). He observed both that these finches closely resembled another finch species on the mainland of South America and that the group of species in the Galápagos formed a graded series of beak sizes and shapes, with very small differences between the most similar. Darwin imagined that the island species might be all species modified from one original mainland species. In 1860, he wrote, “Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.”

Wallace and Darwin both observed similar patterns in other organisms and independently conceived a mechanism to explain how and why such changes could take place. Darwin called this mechanism natural selection. Natural selection, Darwin argued, was an inevitable outcome of three principles that operated in nature. First, the characteristics of organisms are inherited, or passed from parent to offspring. Second, more offspring are produced than are able to survive; in other words, resources for survival and reproduction are limited. The capacity for reproduction in all organisms outstrips the availability of resources to support their numbers. Thus, there is a competition for those resources in each generation. Both Darwin and Wallace’s understanding of this principle came from reading an essay by the economist Thomas Malthus, who discussed this principle in relation to human populations. Third, offspring vary among each other in regard to their characteristics and those variations are inherited. Out of these three principles, Darwin and Wallace reasoned that offspring with inherited characteristics that allow them to best compete for limited resources will survive and have more offspring than those individuals with variations that are less able to compete. Because characteristics are inherited, these traits will be better represented in the next generation. This will lead to change in populations over generations in a process that Darwin called “descent with modification.”

Papers by Darwin and Wallace presenting the idea of natural selection were read together in 1858 before the Linnaean Society in London. The following year Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, was published, which outlined in considerable detail his arguments for evolution by natural selection. Darwin’s book was met with skepticism by many in the scientific community. However, biologists were gradually won over by the immense amount of evidence Darwin provided. Some of that evidence, and evidence discovered since Darwin’s time, is detailed in the next section.

Knowledge Check

Evidence of Evolution

The evidence for evolution is compelling and extensive. Looking at every level of organization in living systems, biologists see the signature of past and present evolution. Charles Darwin dedicated a large portion of his book, On the Origin of Species, identifying patterns in nature that were consistent with evolution, and since Darwin’s time our understanding has become clearer and broader.

Fossils

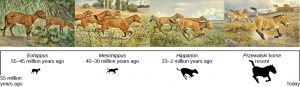

A fossil is the remains or impression of a once-living organism preserved in petrified form in rock. Fossils provide solid evidence that organisms from the past are not the same as those found today; fossils show a progression of evolution. Using radiometric dating and other methods, scientists determine the age of fossils and categorize them all over the world to determine when the organisms lived relative to each other. The resulting fossil record tells the story of the past, and shows the evolution of form over millions of years (Figure 2). For example, highly detailed fossil records have been recovered for sequences of species in the evolution of whales and modern horses. The fossil record of horses in North America is especially rich and many contain transitional fossils: those showing intermediate anatomy between earlier and later forms. The fossil record extends back to a dog-like ancestor some 55 million years ago that gave rise to the first horse-like species 55 to 42 million years ago in the genus Eohippus. The series of fossils tracks the change in anatomy resulting from a gradual drying trend that changed the landscape from a forested one to a prairie. Successive fossils show the evolution of teeth shapes and foot and leg anatomy to a grazing habit, with adaptations for escaping predators, for example in species of Mesohippus found from 40 to 30 million years ago. Later species showed gains in size, such as those of Hipparion, which existed from about 23 to 2 million years ago. The fossil record shows several adaptive radiations in the horse lineage, which is now much reduced to only one genus, Equus, with several species.

Anatomy

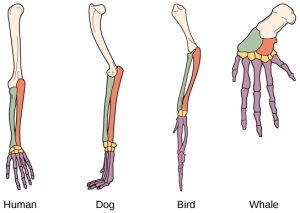

Another type of evidence for evolution is the presence of structures in organisms that share the same basic form even though they perform different functions. For example, the bones in the appendages of a human, dog, bird, and whale all share the same overall construction (Figure 3). However, the limbs of each species is used for different purposes. This similarity in structure results from their origin in the appendages of a common ancestor. Over time, evolution led to changes in the shapes and sizes of these bones in different species, but they have maintained the same overall layout, evidence of descent from a common ancestor. Scientists call these synonymous parts homologous structures.

Some structures exist in organisms that have little or no apparent function, and appear to be residual parts from a past ancestor. For example, some snakes have pelvic bones despite having no legs because they descended from reptiles that did have legs. These unused structures without function are called vestigial structures. Other examples of vestigial structures are wings on flightless birds (which may have other functions), leaves on some cacti, traces of pelvic bones in whales, and the sightless eyes of cave animals (Figure 4).

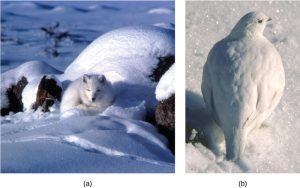

Another evidence of evolution is the convergence of form in organisms that share similar environments. For example, species of unrelated animals, such as the arctic fox and ptarmigan (a bird), living in the arctic region have temporary white coverings during winter to blend with the snow and ice (Figure 5). The similarity occurs not because of common ancestry, indeed one covering is of fur and the other of feathers, but because of similar selection pressures—the benefits of not being seen by predators.

Biogeography

The geographic distribution of organisms on the planet (known as biogeography) follows patterns that are best explained by evolution in conjunction with the movement of tectonic plates over geological time. Broad groups that evolved before the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea (about 200 million years ago) are distributed worldwide. Groups that evolved since the breakup appear uniquely in regions of the planet, for example the unique flora and fauna of northern continents that formed from the supercontinent Laurasia and of the southern continents that formed from the supercontinent Gondwana. The presence of members of the plant family Proteaceae in Australia, southern Africa, and South America is best explained by the plants’ presence there prior to the southern supercontinent Gondwana breaking up (Figure 6).

The great diversification of the marsupials in Australia and the absence of other mammals reflects that island continent’s long isolation. Australia has an abundance of endemic species—species found nowhere else—which is typical of islands whose isolation by expanses of water prevents migration of species to other regions. Over time, these species diverge evolutionarily into new species that look very different from their ancestors that may exist on the mainland. The marsupials of Australia, the finches on the Galápagos, and many species on the Hawaiian Islands are all found nowhere else but on their island, yet display distant relationships to ancestral species on mainlands.

Molecular Biology

Like anatomical structures, the structures of the molecules of life reflect descent with modification. Evidence of a common ancestor for all of life is reflected in the universality of DNA as the genetic material and of the near universality of the genetic code and the machinery of DNA replication and expression. Fundamental divisions in life between the three domains are reflected in major structural differences in otherwise conservative structures such as the components of ribosomes and the structures of membranes in the cells of all living organisms. In general, the relatedness of groups of organisms is reflected in the similarity of their DNA sequences: more closely related organisms have more similar DNA—exactly the pattern that would be expected from descent and diversification from a common ancestor.

DNA sequences have also shed light on some of the mechanisms of evolution. For example, it is clear that the evolution of new functions for proteins commonly occurs after gene duplication events. These duplications are a kind of mutation in which an entire gene is added as an extra copy (or many copies) in the genome. These duplications allow the free modification of one copy by mutation, selection, and drift, while the second copy continues to produce a functional protein. This allows the original function for the protein to be kept, while evolutionary forces tweak the copy until it functions in a new way.

Knowledge Check

Common Misconceptions about Evolution

Although the theory of evolution initially generated some controversy, by 20 years after the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species it was almost universally accepted by biologists, particularly younger biologists. Nevertheless, the theory of evolution is a difficult concept and misconceptions about how it works abound. In addition, there are those that reject it as an explanation for the diversity of life.

“Evolution Is Just a Theory”

Critics of the theory of evolution dismiss its importance by purposefully confounding the everyday usage of the word “theory” with the way scientists use the word. In science, a “theory” is understood to be a concept that has been extensively tested and supported over time. We have a theory of the atom, a theory of gravity, and the theory of relativity, each of which describes what scientists understand to be facts about the world. In the same way, the theory of evolution describes facts about the living world. As such, a theory in science has survived significant efforts to discredit it by scientists, who are naturally skeptical.

While theories can sometimes be overturned or revised, this does not lessen their weight but simply reflects the constantly evolving state of scientific knowledge. In contrast, a “theory” in common vernacular means a guess or suggested explanation for something. This meaning is more akin to the concept of a “hypothesis” used by scientists, which is a tentative explanation for something that is proposed to either be supported or disproved. When critics of evolution say evolution is “just a theory,” they are implying that there is little evidence supporting it and that it is still in the process of being rigorously tested. This is a mischaracterization. If this were the case, geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky would not have said that “nothing in biology makes sense, except in the light of evolution.”

“Individuals Evolve”

An individual is born with the genes it has—these do not change as the individual ages. Therefore, an individual cannot evolve or adapt through natural selection. Evolution is the change in genetic composition of a population over time, specifically over generations, resulting from differential reproduction of individuals with certain characteristics. Individuals do change over their lifetime, but this is called development; it involves changes programmed by the set of genes the individual acquired at birth in coordination with the individual’s environment (Figure 7). When thinking about the evolution of a characteristic, it is probably best to think about the change of the average value of the characteristic in the population over time. For example, when evolution leads to beak-size change in ground finches in the Galápagos, this does not mean that individual beaks on the finches are changing. If one measures the average beak size among all individuals in the population at one time, and then measures the average beak size in the population several years later after there has been a strong selective pressure, this average value may be different as a result of evolution. Although some individuals may survive from the first time to the second, those individuals will still have the same beak size. However, there may be enough new individuals with different bill sizes to change the average bill size.

“Evolution Explains the Origin of Life”

It is a common misunderstanding that evolution includes an explanation of life’s origins. Conversely, some of the theory’s critics complain that it cannot explain the origin of life. The theory does not try to explain the origin of life. The theory of evolution explains how populations change over time and how life diversifies—the origin of species. It does not shed light on the beginnings of life, including the origins of the first cells, which is how life is defined. The mechanisms of the origin of life on Earth are a particularly difficult problem because it occurred a very long time ago, over a very long span of time, and presumably just occurred once. Importantly, biologists believe that the presence of life on Earth precludes the possibility that the events that led to life on Earth can be repeated because the intermediate stages would immediately become food for existing living things. The early stages of life included the formation of organic molecules such as carbohydrates, amino acids, or nucleotides. If these were formed from inorganic precursors today, they would simply be broken down by living things. The early stages of life also probably included more complex aggregations of molecules into enclosed structures with an internal environment, a boundary layer of some form, and the external environment. Such structures, if they were formed now, would be quickly consumed or broken down by living organisms.

However, once a mechanism of inheritance was in place in the form of a molecule like DNA or RNA, either within a cell or within a pre-cell, these entities would be subject to the principle of natural selection. More effective reproducers would increase in frequency at the expense of inefficient reproducers. So while evolution does not explain the origin of life, it may have something to say about some of the processes operating once pre-living entities acquired certain properties.

“Organisms Evolve on Purpose”

Statements such as “organisms evolve in response to a change in an environment,” are quite common. There are two easy misunderstandings possible with such a statement. First of all, the statement must not be understood to mean that individual organisms evolve, as was discussed above. The statement is shorthand for “a population evolves in response to a changing environment.” However, a second misunderstanding may arise by interpreting the statement to mean that the evolution is somehow intentional. A changed environment results in some individuals in the population, those with particular characteristics, benefiting and, therefore, producing proportionately more offspring than those with other characteristics. This results in change in the population if the characteristics are genetically determined.

In a larger sense, evolution is also not goal directed. Species do not become “better” over time; they simply track their changing environment with adaptations that maximize their reproduction in a particular environment at a particular time. Evolution has no goal of making faster, bigger, more complex, or even smarter species. This kind of language is common in popular literature. Certain organisms, ourselves included, are described as the “pinnacle” of evolution, or “perfected” by evolution. What characteristics evolve in a species are a function of the variation present and the environment, both of which are constantly changing in a non-directional way. What trait is fit in one environment at one time may well be fatal at some point in the future. This holds equally well for a species of insect as it does the human species.

“Evolution Is Controversial among Scientists”

The theory of evolution was controversial when Charles Darwin wrote about it in 1859, yet within 20 years virtually every working biologist had accepted evolution as the explanation for the diversity of life. The rate of acceptance was extraordinarily rapid, partly because Darwin had amassed an impressive body of evidence. The early controversies involved both scientific arguments against the theory and the arguments of religious leaders. It was the arguments of the biologists that were resolved after a short time, while the arguments of religious leaders have persisted to this day.

The theory of evolution replaced the predominant theory at the time that species had all been specially created within relatively recent history. Despite the prevalence of this theory, it was becoming increasingly clear to naturalists during the nineteenth century that it could no longer explain many observations of geology and the living world. The persuasiveness of the theory of evolution to these naturalists lay in its ability to explain these phenomena, and it continues to hold extraordinary explanatory power to this day. Its continued rejection by some religious leaders results from its replacement of special creation, a tenet of their religious belief. These leaders cannot accept the replacement of special creation by a mechanistic process that excludes the actions of a deity as an explanation for the diversity of life including the origins of the human species. It should be noted, however, that most of the major denominations in the United States have statements supporting the acceptance of evidence for evolution as compatible with their theologies.

The nature of the arguments against evolution by religious leaders has evolved over time. One current argument is that the theory is still controversial among biologists. This claim is simply not true. The number of working scientists who reject the theory of evolution, or question its validity and say so, is small. A Pew Research poll in 2009 found that 97 percent of the 2500 scientists polled accept the notion that species evolve. The support for the theory is reflected in signed statements from many scientific societies such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which includes working scientists as members. Many of the scientists that reject or question the theory of evolution are non-biologists, such as engineers, physicians, and chemists. There are no experimental results or research programs that contradict the theory. There are no papers published in peer-reviewed scientific journals that appear to refute the theory. The latter observation might be considered a consequence of suppression of dissent, but it must be remembered that scientists are skeptics and that there is a long history of published reports that challenged scientific orthodoxy in unpopular ways. Examples include the endosymbiotic theory of eukaryotic origins, the theory of group selection, the microbial cause of stomach ulcers, the asteroid-impact theory of the Cretaceous extinction, and the theory of plate tectonics. Research with evidence and ideas with scientific merit are considered by the scientific community. Research that does not meet these standards is rejected.

“Other Theories Should Be Taught”

A common argument from some religious leaders is that alternative theories to evolution should be taught in public schools. Critics of evolution use this strategy to create uncertainty about the validity of the theory without offering actual evidence. In fact, there are no viable alternative scientific theories to evolution. The last such theory, proposed by Lamarck in the nineteenth century, was replaced by the theory of natural selection. A single exception was a research program in the Soviet Union based on Lamarck’s theory during the early twentieth century that set that country’s agricultural research back decades. Special creation is not a viable alternative scientific theory because it is not a scientific theory at all; it relies on an untestable explanation. Intelligent design, despite the claims of its proponents, is also not a scientific explanation. This is because intelligent design posits the existence of an unknown designer of living organisms and their systems. Whether the designer is unknown or supernatural, it is a cause that cannot be measured; therefore, it is not a scientific explanation. There are two reasons not to teach nonscientific theories. First, these explanations for the diversity of life lack scientific usefulness because they do not, and cannot, give rise to research programs that promote our understanding of the natural world. Experiments cannot test non-material explanations for natural phenomena. For this reason, teaching these explanations as science in public schools is not in the public interest. Second, in the United States, it is illegal to teach them as science because the U.S. Supreme Court and lower courts have ruled that the teaching of religious belief, such as special creation or intelligent design, violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits government sponsorship of a particular religion.

The theory of evolution, and science in general, is silent on the existence or non-existence of the spiritual world. Science is only able to study and know the material world. Individual biologists have sometimes been vocal atheists, but it is equally true that there are many deeply religious biologists. Nothing in biology rules out the existence of a god; indeed biology as a science has nothing to say about this topic. The individual biologist is free to reconcile her or his personal and scientific knowledge as they see fit. The Voices for Evolution project, developed through the National Center for Science Education, works to gather the diversity of perspectives on evolution to advocate it being taught in public schools.

Knowledge Check

Summary

The development of the theory of evolution represents a pivotal advancement in our understanding of life on Earth. From early ideas of species change to Darwin and Wallace’s formulation of natural selection, scientists have built a framework that explains how species adapt and diversify over time. This theory is supported by a wide range of evidence, including the fossil record, anatomical similarities, biogeographic patterns, and molecular biology, all of which point to common ancestry and gradual change. Although the concept of evolution initially faced skepticism, it has become one of the central unifying principles of biology. By studying the history and evidence of evolution, we gain insight into the processes that have shaped the incredible diversity of life we see today.

Attribution

“Evolution and Its Processes” in OpenStax Concepts of Biology, modified by Sean Whitcomb. License: CC BY

Media Attributions

- Finches is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Horse_evolution © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Homologous_structures © Волков Владислав Петрович is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- cactus leaves is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fox_ptarmigan © Keith Morehouse, USFWS; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Proteaceae biogeography © Doug Ford; OpenStax adapted by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Parhyale_hawaiensis_-_life_cycle © Was a bee is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license