DIFFERENTIATION OF GRAM NEGATIVE BACILLI

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Distinguish between bacteria belonging in the Family Enterobacteriaceae from non-Enterobacteriaceae

State the purpose and principle of the oxidase test, glucose carbohydrate fermentation tests and KIA

Perform and interpret the oxidase test, nitrate reduction test, glucose carbohydrate fermentation tests and KIA

State the significance of glucose fermentation and oxidase test in identifying Gram-negative bacilli

MCCCD OFFICIAL COURSE COMPETENCIES

Describe the modes of bacterial and viral reproduction and proliferation

Utilize aseptic technique for safe handling of microorganisms

Apply various laboratory techniques to identify types of microorganisms

Identify structural characteristics of the major groups of microorganisms

Compare and contrast prokaryotic cell and eukaryotic cell

Compare and contrast the physiology and biochemistry of the various groups of microorganisms

MATERIALS

Stock Cultures: per group of four students

Escherichia coli on TSA slant 8 /2 lab sections at Pecos 6 / 2 lab sections at Williams

Alcaligenes faecalis on TSA slant 8 /2 lab sections at Pecos 6 / 2 lab sections at Williams

Proteus mirabilis on TSA slant 8 /2 lab sections at Pecos 6 / 2 lab sections at Williams

Pseudomonas aeruginosa on TSA slant 8 /2 lab sections at Pecos 6 / 2 lab sections at Williams

Media: per person

MacConkey agar plate

KIA tube

Nitrate broth

Oxidase strip in open Petri dish

Equipment:

Inoculating loop

Inoculating wire

Sterile swabs

Water dropper bottle

BIOCHEMICAL TESTS ALBUM LINK

Gram negative bacilli comprise a vast array of bacteria, yet most clinically significant Gram-negative bacilli can be divided into two groups.

One major group of Gram-negative bacilli is the Family Enterobacteriaceae which contain many genera of organisms such as E. coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Proteus. These Gram-negative, facultative anaerobes are frequently called “enterics” since they are normally found in the intestinal tract of humans and other animals.

The Gram-negative bacilli that are not in the Enterobacteriaceae family are composed of several families but are collectively called Non-Enterobacteriaceae or Nonfermenters (of glucose) to differentiate them from the Enterobacteriaceae. Several of the bacteria in this group include bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Alcaligenes faecalis and Acinetobacter baumanii. These bacteria are mostly found in the environment, yet some of these organisms can cause wound infections and serious life-threatening infections in immunocompromised patients.

The Enterobacteriaceae have four common characteristics:

- They are all Gram-negative bacilli

- They all ferment glucose

- They do not produce oxidase

- They all reduce nitrate to nitrite

The Non-Enterobacteriaceae also have three common characteristics:

- They are all Gram-negative

- They do not ferment glucose

- Many (but not all) are oxidase positive

PRE-ASSESSMENT

PROCEDURE

For this exercise: Work in groups of 4. Each person in the group will work with one of the color dot cultures.

NITRATE Broth REDUCTION TEST

Nitrate broth is used to determine if an organism can reduce nitrate. Some bacteria can reduce nitrate (NO3) to nitrite (NO2) by producing the enzyme nitrate reductase. Other bacteria can reduce nitrate to nitrogen gas by also producing the enzyme nitrite reductase which reduces nitrite to nitrogen gas. Other organisms do not have the ability to reduce nitrate at all.

Nitrate —-nitrate reductase—-> Nitrite —-nitrite reductase—-> Nitrogen Gas

1. Obtain a nitrate broth.

Use a permanent marker to write the color dot, your name (or initials), and the name of the media (nitrate) on the side of the tube.

2. Using a sterile inoculating loop, obtain a small amount of bacteria and inoculate the nitrate broth.

3. Incubate the nitrate broth in the class test tube rack.

AFTER INCUBATION –Add reagents to the incubated nitrate broth. Add 10 drops of 0.8% sulfanilic acid and then add 10 drops of 0.6% N, N-Dimethyl-alpha-naphthylamine. IMMEDIATELY look for a dark red color which indicates the organism used the nitrate reductase enzyme to reduce nitrate to nitrite. This is a positive test result, and no further testing is required. Record your reaction and results on the worksheet. The nitrate reagents have an unpleasant odor. Dispose of the nitrate tubes in the discard rack that will be removed from the lab when lab is over.

If no red color occurs: Dip a wooden applicator stick in zinc powder (just enough to get the stick “dirty”) and drop it into the nitrate broth. The zinc powder reduces nitrate to nitrite. A red color after the addition of zinc is a negative test result. Nitrate was not reduced by the organism, it was reduced by zinc. If a red color does not occur after the addition of zinc, there was no nitrate for zinc to reduce. This is considered a positive result since the organism reduced nitrate to nitrogen gas. Record your reaction and results on the worksheet. The nitrate reagents have an unpleasant odor. Dispose of the nitrate tubes in the discard rack that will be removed from the lab when lab is over.

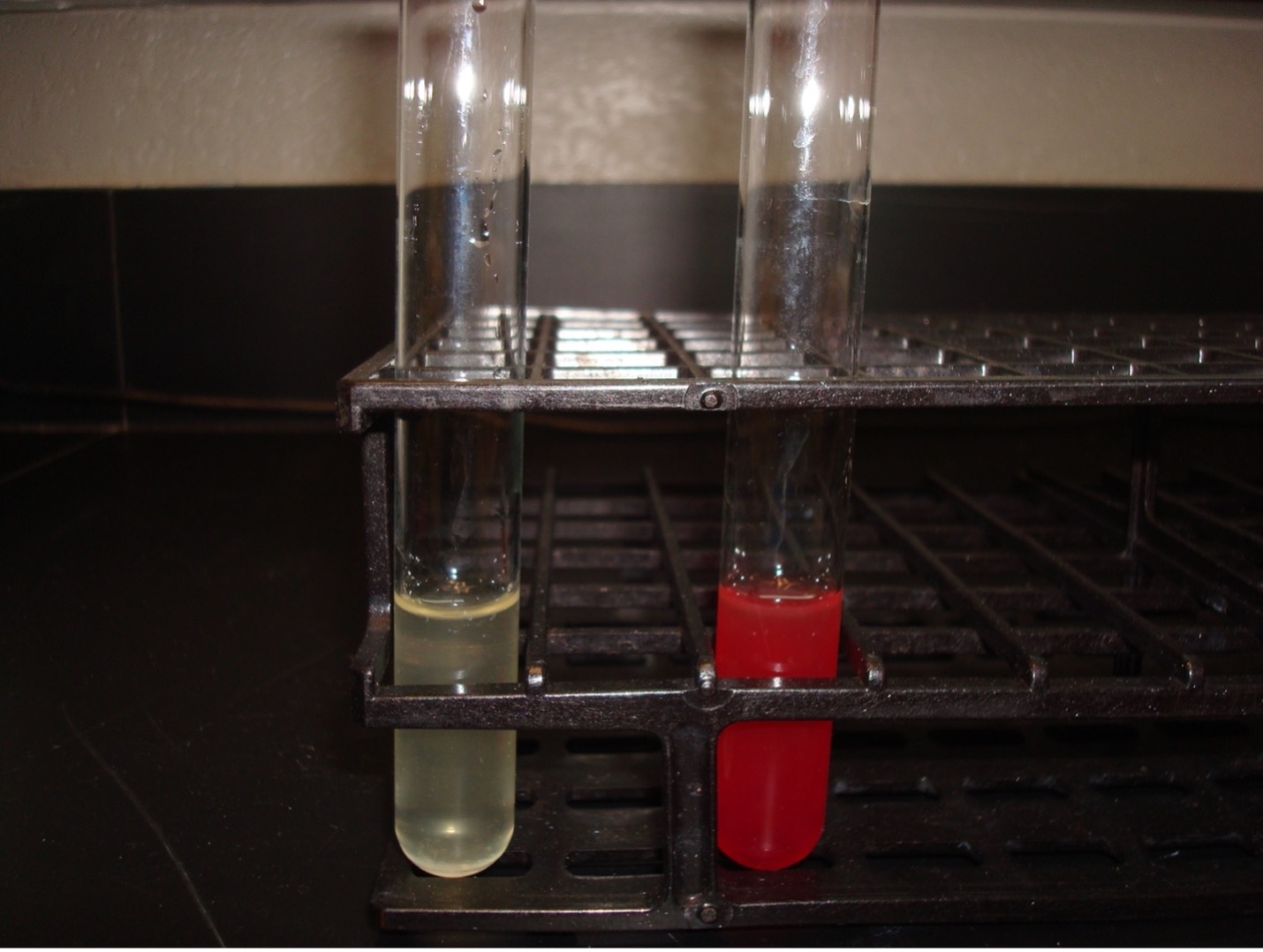

After adding sulfanilic acid & alpha-naphthylamine

Red color = Positive (Nitrate was reduced to Nitrite)

If no color, then add zinc

No color = Positive (Nitrate was reduced to Nitrogen gas)

Red color = Negative (Nitrate was not reduced by the bacteria)

KLIGLER IRON AGAR (KIA)

KIA media contains two carbohydrates, glucose and lactose. It also has a phenol red pH indicator, ferrous sulfate, and peptones in the agar.

KIA media is used to determine if the organisms can ferment glucose with or without gas production. If the organism can ferment glucose, then KIA will also demonstrate if it can ferment lactose. The media can also determine if the organism can produce hydrogen sulfide.

If bacteria cannot ferment glucose, they are called “nonfermenters” and will not be able to ferment any other carbohydrates.

If bacteria can ferment glucose, they are called “fermenters” and can be differentiated by determining if it can also ferment lactose or produce hydrogen sulfide.

1. Obtain a KIA tube and a straight inoculating wire.

Use a permanent marker to write the color dot, your name (or initials), and the name of the media (KIA) on the side of the tube.

2. Use the sterile straight inoculating wire to take an inoculum of the bacteria.

3. Begin by stabbing in the middle of the KIA slant to just above (3-5mm or 0.25 inch) the bottom of the tube. As the needle is withdrawn from the agar, streak the agar slant.

4. Incubate the KIA tube in the class test tube rack.

AFTER INCUBATION –Observe the reactions in the KIA tube and record the reactions/results. Record the reactions and results on the worksheet. Dispose of the KIA tubes in the discard rack.

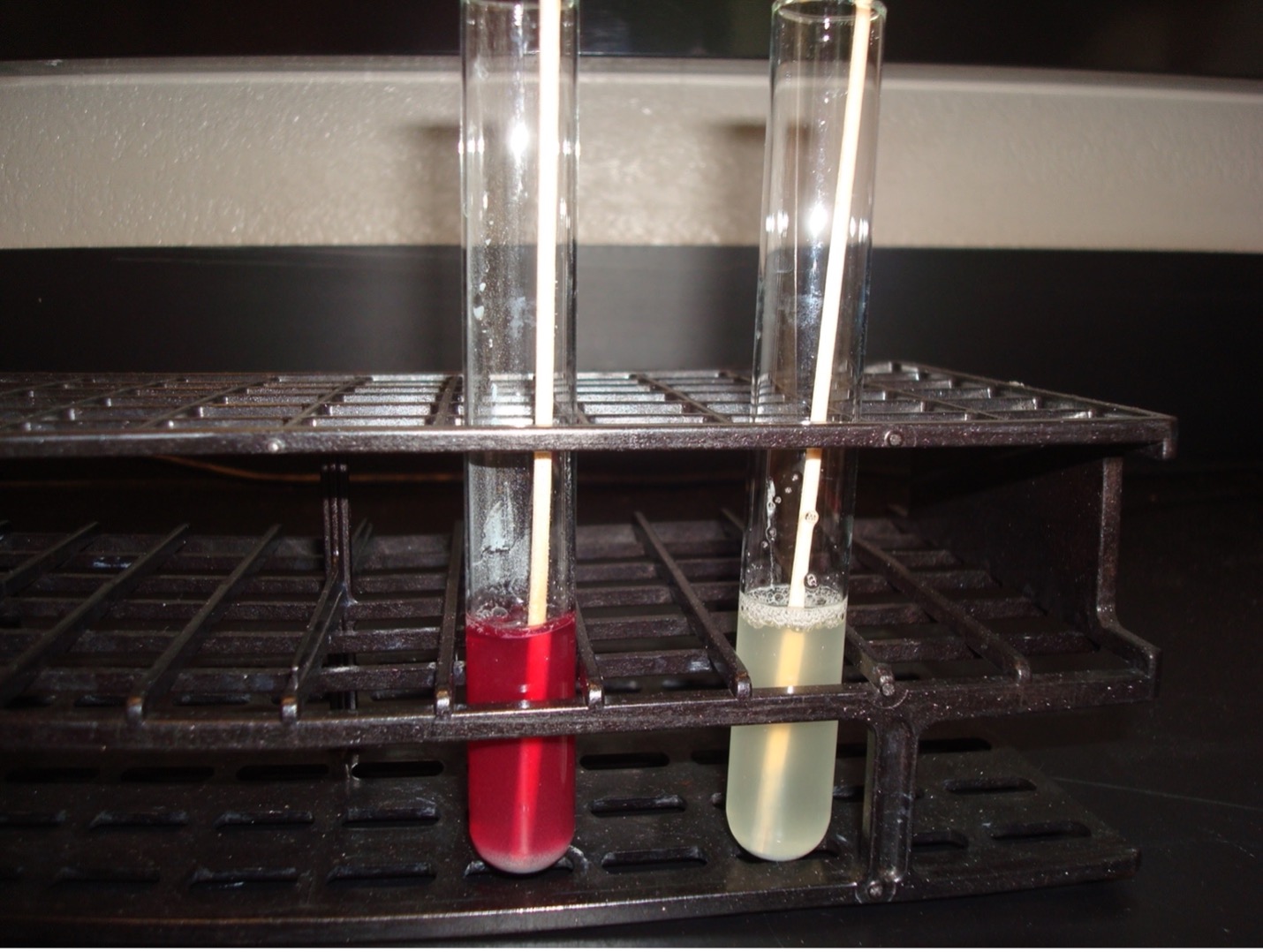

Butt of KIA tube:

Yellow butt = Positive glucose fermentation (A black precipitate may mask the yellow color)

Red butt = Negative glucose fermentation

Gas production from glucose fermentation:

Bubbles or splitting of the agar = Positive for gas (If bacteria cannot ferment glucose, they will not produce gas)

Slant of the KIA tube:

Yellow slant = Positive lactose fermentation

Red slant = Negative lactose fermentation

Hydrogen sulfide production:

Black precipitate in the media = Positive Hydrogen Sulfide Production

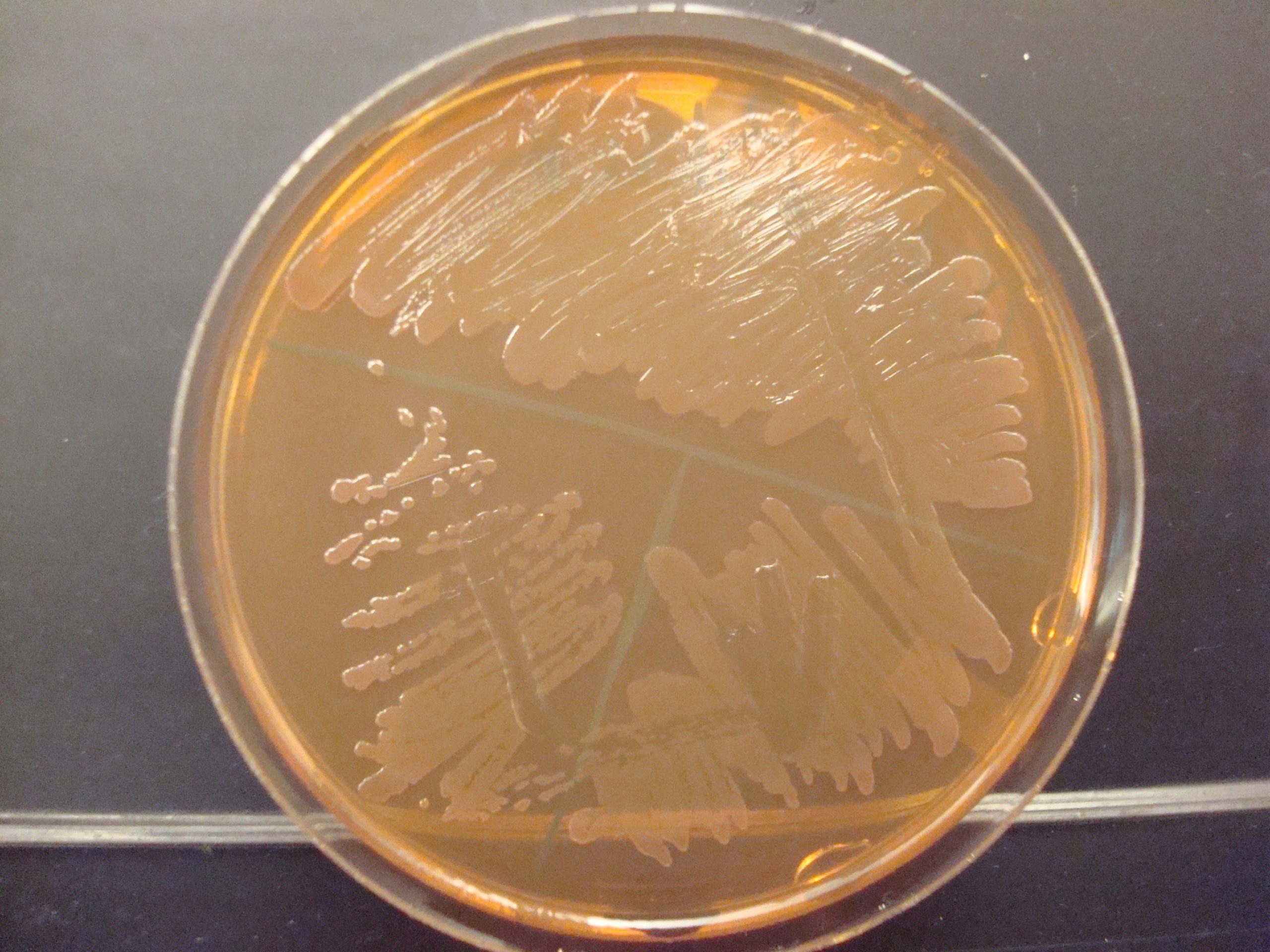

MACCONKEY AGAR (MAC)

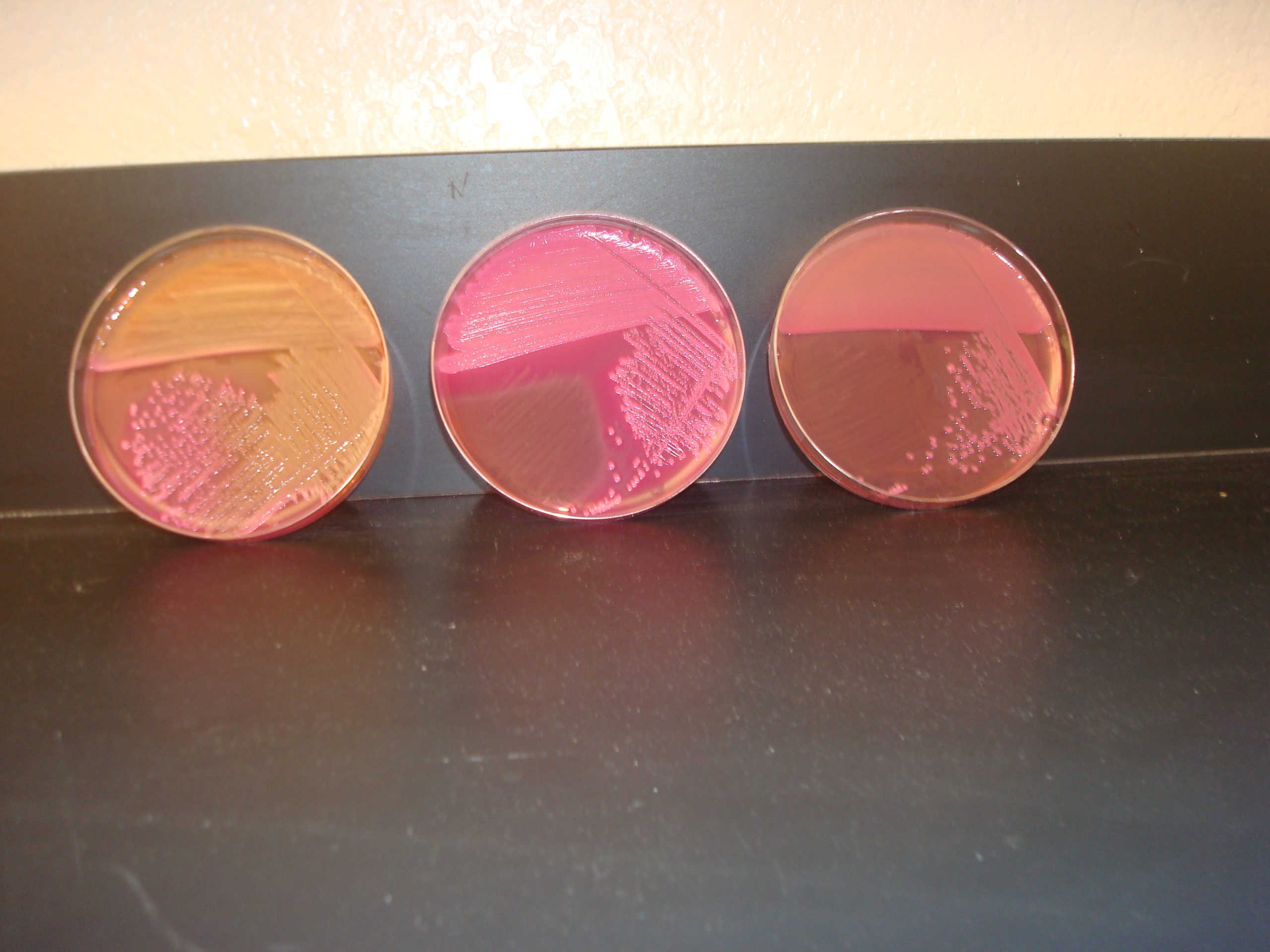

MAC is a selective and differential media. It is used to grow Gram-negative bacilli and differentiate their ability to ferment lactose. MAC has bile salts and crystal violet dye which inhibit Gram-positive bacteria. The media also contains the carbohydrate lactose and a pH indicator. The Gram-negative bacilli that ferment lactose will produce acidic end products thereby changing the color of the pH indicator from clear to hot pink.

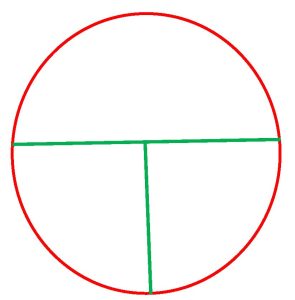

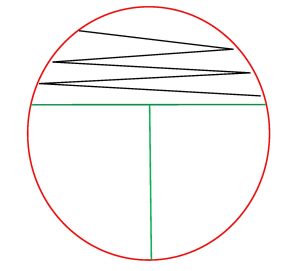

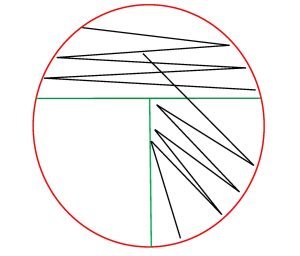

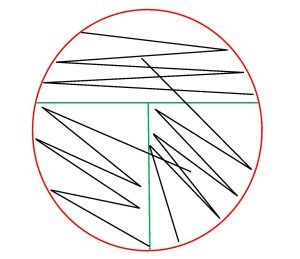

streak plate

1. Obtain a MAC plate and label the agar side with your name, your assigned culture and the name of the media.

2. You will perform a streak plate of your assigned organism on the MAC agar. Divide the MAC plate into 3 sections by drawing a “T” on the bottom of the plate where the media is.

3. Sterilize your inoculating loop in the Bacticinerator and allow it to cool. Remove the cap from your assigned culture with your little finger. Use a sterile inoculating loop to obtain the inoculum from your assigned culture. Recap your assigned culture and place it in a test tube rack.

4. Using your non-dominant hand, open the lid of the MAC plate just enough to fit the loop in.

5. Inoculate the first section of the plate by touching the loop down on the surface of the agar and drawing a zig-zag streak to fill that first area of the plate. Replace the Petri plate lid.

6. Sterilize your inoculating loop in the Bacticinerator and allow it to cool.

7. Open the lid of the plate just enough to fit the loop in. Place the loop in the center of the first section and gently drag the loop one time into the second section. Lightly drag the tip of the loop from side to side in a back-and-forth motion to spread the inoculum to fill the second section. Replace the Petri plate lid.

8. Sterilize the loop in the Bacticinerator and allow it to cool.

9. Open the lid of the plate just enough to fit the loop in. Place the loop in the center of the second section and gently drag the loop one time into the third section. Lightly drag the tip of the loop from side to side in a back-and-forth motion to spread the inoculum to fill the third section. Replace the Petri Plate lid.

10. Sterilize the loop in the Bacticinerator and allow it to cool.

11. Incubate your MAC plate upside down in the class plate tray until the next lab period.

AFTER INCUBATION – Observe your MAC plate. Record the appearance of the growth of the bacteria on this agar. Record the reactions and results on the worksheet. Dispose of the MacConkey agar plates in the biohazard trash.

Growth on media = Gram-negative bacilli

Determine the ability to ferment lactose:

Hot pink colonies (look at the color of the colonies not the color of the media) = Positive for lactose fermentation

Clear colonies = Negative for lactose fermentation (some lactose negative colonies may have a slight pink color due to the transmittance of the media color through the colony)

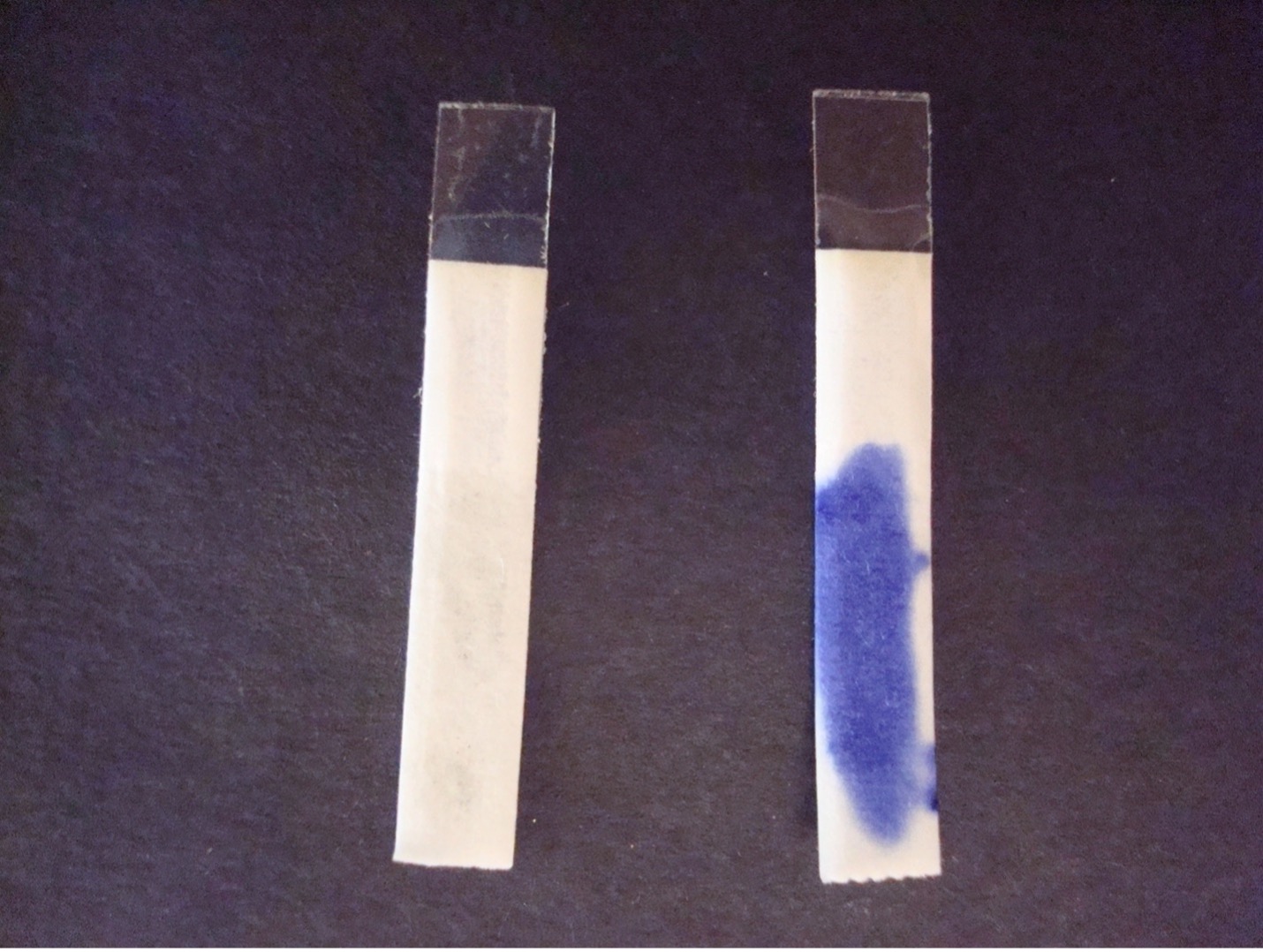

OXIDASE TEST

This test determines if the bacteria can produce the enzyme cytochrome oxidase which transfers electrons in the electron transport chain in cellular respiration. The organism to be tested must be grown on non-inhibitory media such as KIA or TSA because the production of oxidase is easily inhibited by selective media.

1. Place the oxidase strip face up (look at the edges of the strip, they should be pointing down) on a glass slide. Barely moisten the oxidase strip with a small drop of water. Do not over-moisten the strip!

2. Using a sterile swab, obtain a large amount of inoculum from the KIA or TSA plate. Rub the bacteria on the swab on the oxidase strip.

3. Watch for purple color to develop on the strip or swab within 20 seconds. Record the reaction/result on the worksheet. Dispose of the oxidase strip and swab in the biohazard trash. Dispose of the slide in the used slide basin.

Purple color change = Positive

No color change within 20 seconds = Negative

TEST RESULTS OF GRAM NEGATIVE BACILLI

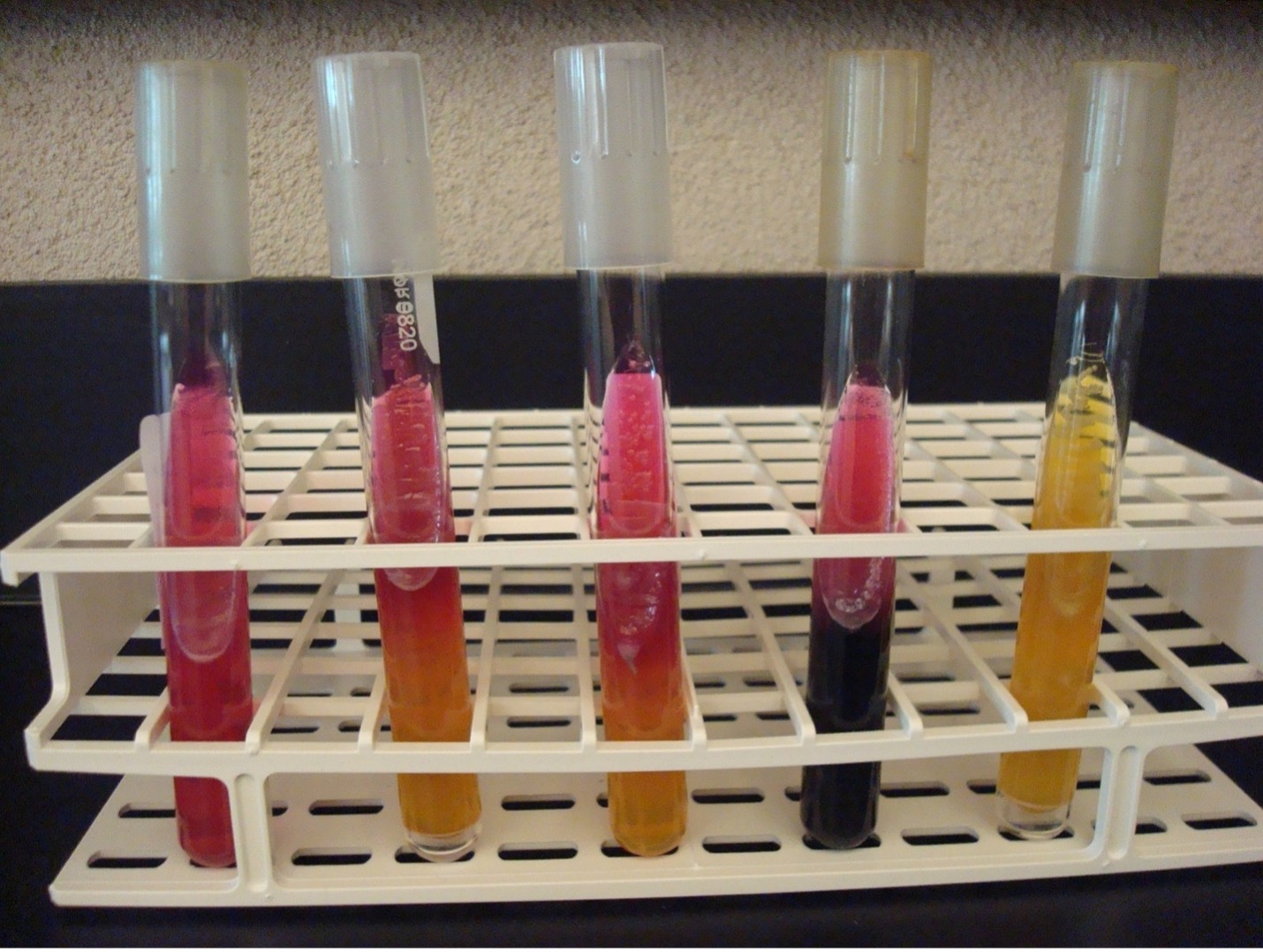

| TEST | Escherichia coli | Proteus mirabilis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Alcaligenes faecalis |

| Oxidase | Negative | Negative | Positive | Positive |

| Nitrate reduction | Positive

(NO3 ->NO2) |

Positive

(NO3->NO2) |

Positive

(NO3->N2) |

Negative

(NO3) |

| KIA Slant | Lactose Positive | Lactose Negative | Lactose Negative | Lactose Negative |

| KIA Butt | Glucose Positive | Glucose Positive | Glucose Negative | Glucose Negative |

| KIA Gas from fermentation | Positive | Not reliable | Negative | Negative |

| KIA H2S | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Lactose fermentation on MacConkey agar | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

POST TEST

DISCOVERIES IN MICROBIOLOGY

DR. EMIL von BEHRING

In 1890, German physiologist Dr. Emil von Behring published an article with Dr. Kitasato Shibasaburō reporting that they had developed “ antitoxins” against both diphtheria and tetanus. They had injected diphtheria and tetanus toxins into guinea-pigs, goats and horses. The animals developed antitoxins (now known to contain antibodies) in their serum. These antitoxins could protect against and cure the diseases in non-immunized animals. In 1892 Dr. Behring began the first human trials of the diphtheria antitoxin, but they were unsuccessful. After the production and quantitation of the antitoxin was improved, in 1894 humans were successfully treated with the antitoxin.

antitoxins” against both diphtheria and tetanus. They had injected diphtheria and tetanus toxins into guinea-pigs, goats and horses. The animals developed antitoxins (now known to contain antibodies) in their serum. These antitoxins could protect against and cure the diseases in non-immunized animals. In 1892 Dr. Behring began the first human trials of the diphtheria antitoxin, but they were unsuccessful. After the production and quantitation of the antitoxin was improved, in 1894 humans were successfully treated with the antitoxin.