11 ENDOSPORE STAIN

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Perform the Schaeffer-Fulton staining technique

Identify the presence of bacterial endospores

Explain why bacterial endospores do not stain with traditional stains

Discuss how bacterial endospores benefit the bacteria that produce them

MCCCD OFFICIAL COURSE COMPETENCIES

Utilize aseptic technique for safe handling of microorganisms

Apply various laboratory techniques to identify types of microorganisms

Identify structural characteristics of the major groups of microorganisms

Compare and contrast prokaryotic cell and eukaryotic cell

Compare and contrast the physiology and biochemistry of the various groups of microorganisms

MATERIALS

Stock Culture:

TSA slant of Bacillus subtilis subspecies spizizenii

Equipment:

1 glass microscope slide per person

Inoculating loop

Test tube rack

Microscope

Endospore Stains: (Schaefer-Fulton)

Malachite green (7.5% aqueous)

Gram’s Safranin

Some Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, can produce resting cells called endospores. They are formed inside the cell membrane of bacteria. These endospores are surrounded by an impervious layer called an endospore coat. Endospores are the most resistant form of life known and can remain dormant for 150,000 years or more. Bacterial endospores are resistant to antibiotics, most disinfectants, and physical agents such as radiation, boiling, and drying. The impermeability of the endospore coat is thought to be responsible for its resistance to chemicals. The heat resistance of endospores is due to a variety of factors:

- Calcium-dipicolinate within the endospore may stabilize and protect the endospore’s DNA.

- Specialized DNA-binding proteins saturate the endospore’s DNA and protect it from heat, drying, chemicals, and radiation.

- Water is removed from the interior of the endospore and the resulting dehydration is thought to be important in the endospore’s resistance to heat and radiation.

- DNA repair enzymes contained within the endospore can repair damaged DNA during germination.

The process of sporogenesis (the formation of endospores within a vegetative cell) is reversible. When an endospore reverts to a vegetative cell (metabolically active, replicating cell), the process is termed germination. Germination is normally induced by physical or chemical damage to the coat of the endospore. Unlike the reproductive spores of fungi and plants, sporogenesis in bacteria is NOT a means of reproduction. A single endospore reverts to one vegetative cell during germination.

Two medically important bacteria that produce endospores are Bacillus and Clostridium. These bacteria are commonly found in the soil and in the lower intestinal tract of humans and animals. The presence of Bacillus in dust accounts for the fact that organisms in the genus Bacillus are common laboratory contaminants. Some species of Bacillusand Clostridium are pathogenic for humans, livestock and wildlife. Bacillus anthracis is the pathogen responsible for anthrax, a disease found in goats, cattle, and sheep which can be transmitted to humans. Persons who handle animals, hides, wool and other animal products are at special risk. There is concern that anthrax endospores might be used in biological warfare as they are easily spread through the air.

Endospores are a unique problem for the food industry since they are resistant to the heating processes that readily kill vegetative cells. Most vegetative cells are killed by temperatures greater than 70oC. Endospores may survive boiling for hours. If the food is not properly processed, the endospores may germinate, produce toxins and cause food poisoning.

All the medically important Clostridium produce toxins. Clostridium botulinum is the causative agent of botulism, a particularly lethal type of food poisoning. A small coke bottle of botulism toxin is potent enough to eliminate the entire human race!

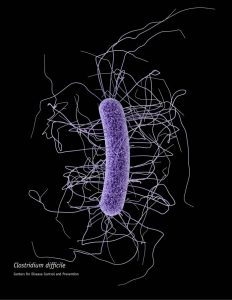

Clostridium perfringens causes gas gangrene and food poisoning. Clostridium tetani causes tetanus or “lockjaw”. Clostridium difficile causes toxic enterocolitis and pseudomembranous colitis. This is usually observed in people who have been on broad-spectrum antibiotics for a long period of time. These antibiotics kill the normal microbiome in the intestinal tract and allow C. difficile to grow unchallenged. This infection is a common cause of healthcare associated infection (HAI) which is difficult to eradicate from the healthcare environment due to the ability to produce resistant endospores.

PRE-ASSESSMENT

PROCEDURE

Perform an endospore stain

1. Prepare a smear of Bacillus using the techniques learned in preparing smears for Gram staining.

2. Allow the smear to air dry or dry the slide on the slide warmer.

3. Begin the stain procedure with the dry slide on the slide warmer. Put a small piece of filter paper on top of the slide and add malachite green to the filter paper. Add more dye if the paper starts to dry out.

4. After 5 minutes on the slide warmer, transfer the slide to the stain rack for another 5 minutes.

5. Remove the filter paper from the slide, place it on a paper towel and dispose of it in the trash.

6. Rinse the slide with deionized water. Shake off excess water.

7. Add Gram’s safranin to the smear. Allow this counterstain to remain on the slide for 2 minutes.

8. Rinse your smear with deionized water and blot dry with bibulous paper or paper towel. Observe the results using the oil immersion lens of your microscope. Draw your observations in the worksheet.

POST TEST

DISCOVERIES IN MICROBIOLOGY

DR. JOHN BARTLETT

In 1975 American physician John Bartlett began trials investigating the problem of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis. His work led the discovery of Clostridium difficile. C. difficile is the most common cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea in the developed word. Vancomycin, isolated from Streptomyces orientalis, was discovered in 1955 by Mack H. McCormick and colleagues at Eli Lilly. Vancomycin is often used to treat C. difficile infections.