6 HAND WASHING TECHNIQUES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Demonstrate the transmission of microbes from person to person and surfaces

Recognize the importance of hand hygiene in reducing the transmission of infection

Demonstrate the correct technique for proper hand washing

Demonstrate the correct technique when using a hand sanitizer

MCCCD OFFICIAL COURSE COMPETENCIES

Identify the significant and critical contributions to microbiology

Use significant and critical contributions to microbiology to illustrate and explain the collaborative nature of science

Describe and compare the effectiveness of physical and chemical methods of microbial control

MATERIALS

TSA plates – 7 per table

Hand soap

Alcohol-based hand sanitizer

Abrasive Soap (Soap with pumice)

Glo Germ powder

UV light

The human skin is inhabited by a diverse group of microorganisms called normal flora or microbiota. The normal flora of the skin includes Staphylococcus, diphtheroids, and fungi and is usually non-pathogenic. In addition to the normal flora, there are transient microorganisms that are picked up by contact with any inanimate surface (fomites), including countertops, cell phones, keyboards, and toys, as well as animals and other people. Transient microbes are present only for days or weeks. Most transient microbes are easily removed by hand washing because they are contaminants on the skin. Normal flora is more difficult to remove by hand washing because these microbes reside in hair follicles and are entrenched in the skin.

The importance of hand washing in preventing the spread of infectious disease is credited to the observations of Ignaz Semmelweis in 1846. He noted that the lack of hand hygiene was directly related to the incidence of puerperal fever (childbirth fever). Medical students would go directly from the autopsy room to the patient’s bedside and assist in child delivery without washing their hands. As head of obstetrics, Semmelweis ordered the medical students to wash their hands with a chloride of lime solution and the death rate due to puerperal fever fell from 12% to 1.2% in only one year. This success was short lived, as complaints by doctors and medical students forced Semmelweis to stop the hand washing order, causing the death rate from puerperal fever to increase once again!

The failure of medical professionals to wash their hands before examining patients has resulted in a serious increase in nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections in patients. Scientists estimate that over 80% of infections are transmitted by hands. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state that “hand washing is the single most important procedure for preventing nosocomial infections”, yet recent studies in hospitals show hand washing rates as low as 31%.

Washing hands with soap and water is the best way to reduce the number of microbes on them in most situations. Soap and water are more effective at removing or inactivating microbes such as Cryptosporidium, Norovirus and Clostridium difficile. If hands are visibly soiled, then hand washing is the only effective way to reduce the numbers of microbes. The surfactants in soap lift soil and microbes from the skin.

If soap and water are not available, then use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. Non-alcohol based hand sanitizers are not as effective in inactivating microbes and may help increase the number of resistant organisms.

The biggest mistake that many people make is taking too little time for hand hygiene. Twenty seconds of scrubbing is the minimum amount of time necessary when using either soap and water or hand sanitizer.

Directions for proper hand washing:

1. Wet hands and lather an adequate amount of soap (enough to cover all surfaces of your hands).

2. Rub palms together with fingers interlaced.

3. Rub the right palm over the back of the left hand with interlaced fingers and vice versa.

4. Hook fingertips together and rub the front and back.

5. Use rotational rubbing of the right thumb clasped in the left palm and vice versa.

6. Scratch the fingertips in the palm of the opposite hand to get soap underneath the nails.

7. Using a rotational movement, wash both wrists.

8. Thoroughly rinse off the soap under running water.

9. Thoroughly dry your hands with a disposable paper towel.

10. Turn of the faucet using the paper towel.

Directions for using hand sanitizer:

1. Dispense an adequate amount of hand sanitizer into your palm (enough to cover all surfaces of your hands).

2. Rub hands together until the product is completely dry.

3. Pay attention to fingertips, nails, between fingers and backs of the hands.

PRE-ASSESSMENT

procedure

In this exercise we will examine the transmission of microbes, effectiveness of washing hands with water, soap and water, soap and water with a scrub brush, and hand sanitizer.

Procedure #1

Work as a table to complete this exercise.

1. Each student at your table will be assigned a different hand cleaning method: just water, soap and water, abrasive soap and water, or hand sanitizer.

2. Label your plate with your name and either water, soap, abrasive soap, or hand sanitizer.

3. The hand sanitizer group should divide their TSA plate in half and label the sections 1 and 2.

4. The water, soap and water, and abrasive soap and water groups should take 2 TSA plates. Divide both TSA plates into two sections. Label the sections 1 through 4.

5. Touch section 1 of the TSA plate with your fingers. This section will show you how much bacteria are on your hands before you wash them.

6. According to your assigned hand hygiene method, begin cleaning your hands. Sing “Happy Birthday” once, and then stop washing. If you are assigned the hand sanitizer, mimic this hand washing technique.

7. If using water, shake off the excess water. Dry your hands with a paper towel and touch section 2 of the TSA plate. If you are assigned the hand sanitizer, you are done.

8. Other students continue washing your hands. Sing Happy Birthday again, and then stop washing. Shake off the excess water. Dry your hands with a paper towel, then touch section 3 of the TSA plate.

9. Continue washing your hands again. Sing Happy Birthday and then stop washing. Shake off the excess water. Dry your hands with a paper towel, then touch section 4 of the TSA plate.

10. Incubate the TSA plates lid side down at 37◦C until the next period.

AFTER INCUBATION-Record the results on the worksheet.

Procedure #2

Work as a table to complete this exercise.

1. Assign each student at the table a number from 1 to 4.

2. Student #1: Shake a nickel size amount of Glo Germ powder into the palm of your hand. Dab your fingertips in the powder and rub your hands together.

3. Student #1: Shake hands with Student #2 using the technique shown below.

4. Student #2: Shake hands with Student #3 using the same technique.

5. Student #3: Shake hands with Student #4 using the same technique.

6. Shine UV light on your hands.

7. Indicate on the diagram on the worksheet where you see the fluorescing Glo Germ powder.

8. Using proper hand washing technique, wash your hands with soap and water.

9. Dry your hands on a disposable paper towel.

10. Shine the UV light on your hands.

11. Indicate on the worksheet where you still see fluorescing Glo Germ powder.

12. Shine the UV light on objects that you touched while performing the experiment. Observe where the Glo Germ powder was transmitted by your hands.

POST TEST

DISCOVERIES IN MICROBIOLOGY

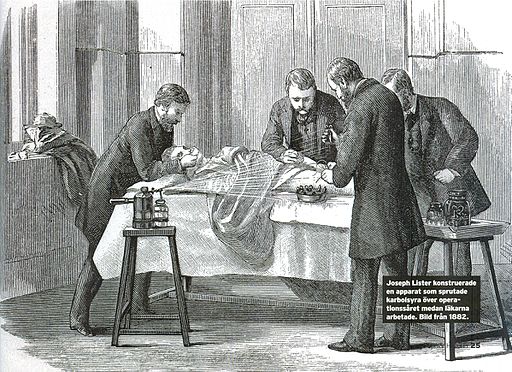

DR. JOSEPH LISTER

In the 1800’s it was common to see the following note in a surgical report, “operation successful but the patient died”. In 1864-1866, before he developed antisepsis, 46% of British surgeon Dr. Joseph Lister’s surgical patients died of infection after surgery. Many people believed “bad air”, or miasma, was responsible for infection in surgical wounds. Hospital wards were often aired out at midday as a precaution against the spread of infection via miasma. Phenol (or carbolic acid) had been used preventing decay and neutralize the stench of dead animals and human cadavers. Frederick Calvert, Alexander McDougall, and Angus Smith used a powdered form of carbolic acid as a deodorizing agent to treat municipal sewage across the United Kingdom, most notably during London’s famous “Great Stink” of 1858. Dr. Lister read the work of Ignaz Semmelweis on hand washing and Pasteur’s work on spontaneous generation and fermentation. Dr. Lister was convinced that infection of surgical wounds was due to tiny living creatures in the air entering surgical wounds He instructed surgeons under his responsibility to wear sterilized gloves and wash their hands before and after operations with a 5% carbolic acid solution. Instruments were also washed in the same solution and assistants sprayed the solution in the operating room. One of his additional suggestions was to stop using porous natural materials in manufacturing the handles of medical instruments. After implementing his new technique (1867-1870), 15% of Dr. Lister’s patients died of infection after surgery. More fortunate than many pioneers, Dr. Lister saw the almost universal acceptance of his antisepsis techniques during his life. Dr. Lister’s work was an inspiration to others. Joseph Lawrence, a chemist living in Missouri, developed an alcohol-based formula for an antiseptic mouthwash in 1879 that he named “Listerine” in his honor.

In the 1800’s it was common to see the following note in a surgical report, “operation successful but the patient died”. In 1864-1866, before he developed antisepsis, 46% of British surgeon Dr. Joseph Lister’s surgical patients died of infection after surgery. Many people believed “bad air”, or miasma, was responsible for infection in surgical wounds. Hospital wards were often aired out at midday as a precaution against the spread of infection via miasma. Phenol (or carbolic acid) had been used preventing decay and neutralize the stench of dead animals and human cadavers. Frederick Calvert, Alexander McDougall, and Angus Smith used a powdered form of carbolic acid as a deodorizing agent to treat municipal sewage across the United Kingdom, most notably during London’s famous “Great Stink” of 1858. Dr. Lister read the work of Ignaz Semmelweis on hand washing and Pasteur’s work on spontaneous generation and fermentation. Dr. Lister was convinced that infection of surgical wounds was due to tiny living creatures in the air entering surgical wounds He instructed surgeons under his responsibility to wear sterilized gloves and wash their hands before and after operations with a 5% carbolic acid solution. Instruments were also washed in the same solution and assistants sprayed the solution in the operating room. One of his additional suggestions was to stop using porous natural materials in manufacturing the handles of medical instruments. After implementing his new technique (1867-1870), 15% of Dr. Lister’s patients died of infection after surgery. More fortunate than many pioneers, Dr. Lister saw the almost universal acceptance of his antisepsis techniques during his life. Dr. Lister’s work was an inspiration to others. Joseph Lawrence, a chemist living in Missouri, developed an alcohol-based formula for an antiseptic mouthwash in 1879 that he named “Listerine” in his honor.