12.4 Types of Floods and Flood Features

Floods, an overflow of water in one place, are a natural part of the water cycle, but they can be terrifying forces of destruction. Floods can occur for a variety of reasons, and their effects can be minimized in several ways. Perhaps unsurprisingly, floods tend to affect low-lying areas most severely, although they can occur anywhere. Floods usually occur when precipitation falls more quickly than that water can be absorbed into the ground or carried away by rivers or streams. Waters may build up gradually throughout weeks when an extended period of rainfall or snowmelt fills the ground with water and raises stream levels. The discharge levels of streams are highly variable depending on the time of year and on specific variations in the weather from one year to the next (1).

Types of Floods

Flash floods are sudden and unexpected, taking place when very heavy rains fall over a very brief period. A flash flood may do its damage miles from where the rain falls if the water travels far down a dry streambed so that the flash flood occurs far from the location of the original storm. These floods can turn a dry stream channel into a raging river in a matter of minutes (Dastrup, 2020).

While flash floods can occur anywhere, they are more likely in mountainous regions and areas with small drainage basins that can be easily overcome by a sudden, intense influx of water. In the dry, desert southwest, the lack of vegetation and clay-rich soils also play a role. Densely vegetated lands are less likely to experience flooding, because plants slow down water as it runs over the land, giving it time to enter the ground. Even if the ground is too wet to absorb more water, plants still slow the water’s passage and increase the time between rainfall and the water’s arrival in a stream; this could keep all the water falling over a region to hit the stream at once. While clay-rich soils can hold huge amounts of water, they don’t absorb that water quickly, so water is more likely to run off.

Historic Flooding: Flash Floods

While typically smaller events, flash floods are often unexpected and can be deadly.

- Big Thompson Canyon, Colorado, 1976. Within a few hours of the initial rainfall, water accumulated in a dry wash in the middle of the night and killed 144 people.

- Antelope Canyon, AZ, 1997. A beautiful tourist destination became deadly to 11 hikers that could not get out of the steep walled-canyon when waters came rushing through from an unseen cloudburst in the distanct.

- Verde River, Payson, AZ, July 2017. A family of 10 were swept and drowned by a flash flood in a tributary of the East Verde River while on playing in a popular swimming area. Monsoonal rains 29 miles away had raced down an area that had been burned during a recent forest fire.

Regional Floods

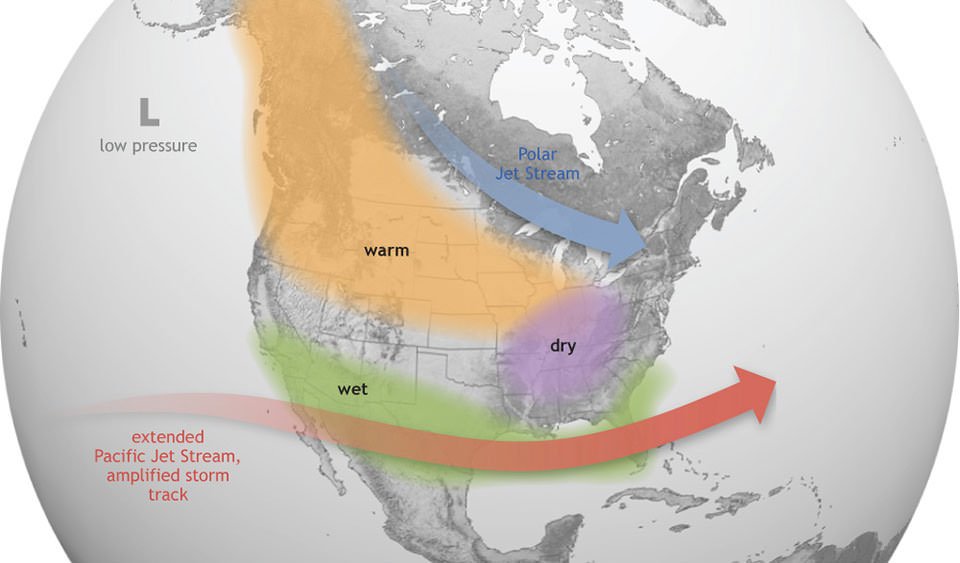

When flooding occurs after an extended period of rainfall, the increase in volume of water within a stream and its tributaries will eventually overflow with water into the adjacent floodplain. This is the classic vision of flooding, and is also the most common type of flooding event. This is sometimes referred to as riverine flooding. Along major rivers with very large drainage basins, the timing and size of floods can be predicted in advance with considerable accuracy. Generally, the smaller the drainage basin, the more difficult it is to forecast the flood. Prolonged seasonal rainfall and associated snowmelt is often the cause of these types of floods, but they can be heightened by storm events as well. Global water circulation patterns are also often to blame.

For example, El Nino is a global weather event that causes the trade winds to weaken and subsequently push warm, wet air across the Gulf Coast and southeastern United States. Both flash and regional flooding can occur from the storms generated by this event.

Historic Flooding: Regional Floods

Heavy rainfall of extended periods of time can overwhelm large drainage basins.

- Mississippi River, 1927. Over 500 people were killed, and this is considered the most destructive regional flood in the history of the US.

- Ohio River, 1937 This flood event was so widespread, people were left homeless up to 30 miles away from the river.

- Mississippi River, 1993. This was the second costliest on flood event on record, partly due to the amount of time that areas were flooded. The waters stayed at flood stage for 81 consecutive days.

- Arizona, 1993. The El Nino event caused 3 months of abnormally high precipitation across most of Arizona. The combination of rain and snow generated the largest floods on record for many rivers in the state.

Flood recurrence

Floods naturally happen regularly on streams. If you’ve ever heard someone talking about the “100-year flood”, this means that on average we can expect a flood of this size or greater to occur within a 100-year period. There are also 5-year, 10-year, and up to 1000-year floods. While this doesn’t tell us exactly which year the flood event will occur in, it gives us an idea of the size and frequency to expect.

The U.S. Geological Survey has thousands of gages on streams throughout the country in order to track flow and calculate recurrence intervals, like the 100-year flood. The amount of actual water in the channel is related specifically to the stream being assessed, as the discharge of every stream is variable. Geologists use statistical probability (chance) to put a context to floods and their occurrence. If the probability of a particular flood magnitude being equaled or exceeded is known, then risk can be assessed. To determine these probabilities, all the annual peak streamflow values measured at a gage are examined and every stream had a different magnitude calculation for floods. So, the 100-year flood magnitude for the Salt River, which flows through central Phoenix is calculated to be 300,000cfs, although very few floods have been recorded and measurements have only been taken since the late 1890’s. However, the same 100-year flood calculation for the Mississippi River (the largest stream in the United States), is nearly 1,800,000cfs!

Flood Features

A stream typically reaches its greatest velocity when it is close to flooding over its banks. This is known as the bank-full stage, as shown in the figure below. As soon as the flooding stream overtops its banks and occupies the wide area of its flood plain, the water has a much larger area to flow through and the velocity drops significantly. At this point, sediment that was being carried by the high-velocity water is deposited near the edge of the channel, forming a natural bank or levée. As numerous flooding events occur, these ridges buildup under repeated deposition. These levees are part of a larger landform known as a floodplain. A floodplain is the relatively flat land adjacent to the stream that is subject to flooding during times of high discharge and are popular sites for development due to their rich soils, access to waterways, and nice scenery (1).

![Attribution 4.0 International The development of natural levées during flooding of a stream. The sediments of the levée become increasingly fine away from the stream channel, and even finer sediments — clay, silt, and fine sand — are deposited across most of the flood plain. [SE]](http://opentextbc.ca/geology/wp-content/uploads/sites/110/2015/08/natural-lev%C3%A9es.png#fixme)

Because floodplains are flat areas that have had regular deposits of silt and clay over time, they become fertile and are often used for agriculture. The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) estimates that in 2018, as many as 13 million Americans live on the floodplain in the 100-year flood zone, although the number is likely much higher due to the amount of time it takes to update flood maps in highly populated areas.

an overflow of water in one place

a flat-lying area of land next to a stream that experiences flooding during periods of high discharge

cubic feet per second. This is a measurement to calculate stream discharge