3.9 The Rock Cycle

Minerals vs. Rocks

So, we’ve covered that minerals are:

- Naturally Occurring

- Inorganic

- Crystalline (solid with a repeating internal structure)

- Definite chemical composition

So, then what are rocks? Rocks are naturally occurring and coherent aggregate of one or more minerals.

The Rock Cycle: Recycle and Reuse

We previously learned that Earth is an efficient recycler of its solid materials through the process of Plate Tectonics, in which the rigid oceanic lithosphere will eventually descend into the asthenosphere, melt, and form again at spreading centers. Another way in which the Earth can rework and recycle its crust is through the Rock Cycle.

The Rock Cycle describes how the three main rock types that compose the Earth’s lithosphere are constantly transformed into one another through geologic processes. These three rock types, which we will learn about in more detail in the following chapters, are Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic Rocks. For now, let’s focus on the process that create these different rock types.

Igneous Rocks: Melting, Cooling, and Crystallization

Extremely hot rock from the mantle that has been melted or partially melted is called molten. We call this molten rock magma. When magma rises to the crust and erupts at the Earth’s surface from volcanoes, it is called lava. Eventually these molten materials cool and solidify, and they might grow minerals through crystallization. The solid products from magma, lava, or volcanic activity are called Igneous Rocks.

Igneous rocks are not exclusively formed from material in the mantle! Sometimes a sedimentary rock can be buried deep within the crust and come in contact with magma, which causes the molten rock’s composition to change. The same can happen with metamorphic rocks, or even preexisting igneous rocks. When ANY type of rock is melted, it becomes molten, and it thus has the potential to become an igneous rock.

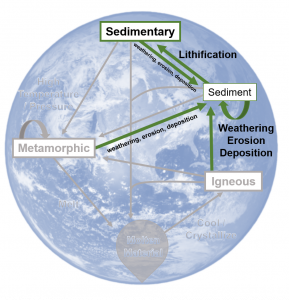

Sedimentary Rocks: Weathering, Deposition, and Lithification

When any rock is exposed to the Earth’s surface, it will undergo weathering and erosion, which produces sediment. Weathering is the physical and chemical breakdown of rocks into smaller fragments by the atmosphere, hydrosphere, or biosphere. Erosion is the removal of those fragments from their original location. The sediment from the original rock will be transported by streams, glaciers, or wind, but it will ultimately accumulate on the Earth’s surface due to gravity. This accumulation is called deposition.

The deposited sediments will eventually build in layers and become buried in the Earth’s surface. These sediments will eventually become solid rock through a process called lithification, which requires both compaction and cementation of the loose solids. The weight of the overlying layers will compact the sediment closer together, and as groundwater leaks between the individual grains, it will glue or cement the sediment as solid rock.

In other circumstances, weathering strips rocks of their very elements at an atomic level; these elements later precipitate as new solids in oceans or lakes. Both lithification and precipitation will produce Sedimentary Rocks.

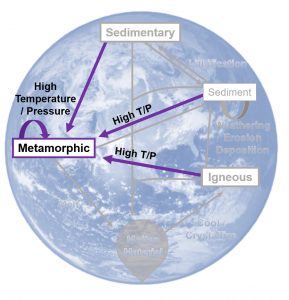

Metamorphic Rocks: Burial, Deformation, and Exhumation

When any type of rock – igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic – is buried within the Earth’s lithosphere, it may be exposed to high temperatures and pressures at depth. The alteration of rock by this heat and pressure is called Metamorphism.

Rocks will change during metamorphism because the minerals that compose them are only stable under a specific range of temperatures and pressures. Therefore, greater heat and pressure will cause new minerals to grow, and in some rocks, the pressure will squeeze and stretch minerals in lined or waved patterns called foliation. These transformed and deformed products of heat and pressure are called Metamorphic Rocks.

Metamorphic rocks do not form at the Earth’s surface as the heat and/or pressures required for metamorphism can only be found kilometers deep within the lithosphere. Nevertheless, we do see metamorphic rock formations at the surface of the Earth. Why is this? Sometimes the deeply buried layers of metamorphic rock are forced toward the light of day by mountain building processes or the sudden weathering and erosion of overlying rocks. This process is called Exhumation, and it is why we can see a variety of rocks from different time periods in Earth’s history!

Written in Stone

The Rock Cycle is truly a cycle. There is generally no single point in which it “begins” or “ends”, and it has been operating for billions of years. There is a natural tendency to think that the rocks on Earth’s surface progress as Igneous -> Sedimentary -> Metamorphic -> Igneous, but that is not the case. The reality is that any type of rock on Earth’s surface has the potential to become any other type of rock through geologic processes!

For example, a sedimentary rock might be buried deep within the Earth’s surface and melt in contact with a plume of magma. The magma and molten sedimentary rock mix and produce a new igneous rock. That igneous rock is then buried very deeply in the crust and becomes warped and deformed; it transforms into a metamorphic rock. Finally, after hundreds of millions of years, the metamorphic rock formation is exhumed and weathered away. The fragments of that metamorphic rock lithify to form a brand new sedimentary rock. What a cycle!

In the following exercise, think about how the processes that form each type of rock relate to each other.

One last thing! The processes involved in the rock cycle, and the rocks themselves, tell a story of the events that happened in Earth’s 4.54 billion year history. While even the best geologic cannot reconstruct every page of Earth’s story from a single rock formation, they can get a glimpse of what might have happened in a region to form a certain type of rock.

An igneous rock can tell us a story of magma chambers or volcanic activity. Sedimentary rocks tell us where rivers, deserts, beaches, and oceans once resided, and metamorphic rocks help us reconstruct the times tectonic plates collided or spread apart from one another.

In his poem, Auguries of Innocence, Walt Whitman once wrote:

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand” [1]

What will you see in an entire rock?

***See 3.10 for Text and Media Attributions

a substance that contains at least one mineral or mineraloid.

The theory that the outer layer of the Earth (the lithosphere) is broken in several plates, and these plates move relative to one another, causing the major topographic features of Earth (e.g. mountains, oceans) and most earthquakes and volcanoes.

The outer, relatively rigid layer of the Earth that responds to the emplacement of a load by flexural bending.

A ductile but solid, hot layer in the Earth composed of the lower crust and upper mantle that flows like putty over long periods of time. It drives the movement of the rigid tectonic plates riding above.

A region on the ocean floor where magma from an active divergent boundary is creating new oceanic lithosphere, thus pushing or spreading the older lithosphere outwards.

The transformation of the three main rock types - igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic - into one another through geologic processes over long timescales.

Rocks that crystallize from molten materials beneath the Earth surface or from volcanic processes.

rocks that cement together from weathering products, either from sediments or chemical ions in water.

Rocks that form when any type of preexisting rock is warped or transformed under elevated temperatures and pressures.

A hot interior layer of solid rock between the crust and core that is capable of plastic flow. The mantle is the largest layer of Earth.

molten rock that can be found beneath the Earth's surface.

The thin, outermost layer of Earth composed of rigid rock, which is home to all known life on the planet.

molten rock that has erupted at the Earth's surface due to volcanic processes.

a solid, inorganic, and crystalline substance that has a predictable chemical composition and form by natural processes.

The process in which another substance, usually a fluid, becomes a solid and grows minerals.

The process of physically or chemically breaking down, transforming, or dissolving existing rock with contact by water, the atmosphere, or biosphere.

the process in which a material is worn away by a stream of liquid (water) or air, often due to the presence of abrasive particles in the stream

The accumulation of rocky material, soil, sediment, and debris due to gravity.

The solidification of loose sediment materials as solid sedimentary rock through compacting pressures and cementation.

The process in which gravity and the pressure from overlying layers of rock cause loose sediments to press together.

The process in which fluids, such as water, move into the pore spaces between loose sediments and - through chemical reactions - act as a bonding agent between the grains.

A pure substance that is not composed of any other ingredients found in the Periodic Table of Elements. One atom can be composed of only one element and form bonds with other elements.

When the cloud droplets combine to form heavier cloud drops which can no longer "float" in the surrounding air, it can start to rain, snow, and hail... all forms of precipitation, the superhighway moving water from the sky to the Earth's surface.

The alteration of preexisting rock by elevated temperatures or pressures, usually beneath the Earth's surface.

The upward movement of buried rock toward Earth's surface by isostasy and erosion of overlying layers.