4.1 Molten Materials

Magma vs. Lava

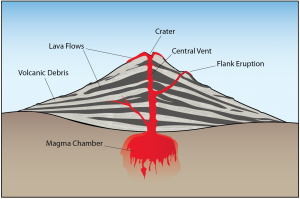

You may have heard both magma and lava used to refer to molten rock. This can be confusing, especially since BOTH of these terms do apply to hot, melted rock. So what’s the difference, anyway? It comes down to location. Magma is hot, molten rock that exists beneath the Earth’s surface. It can be found in the crust right below a volcano or within the mantle. For a volcano to erupt, it must have a source of magma.

Lava, on the other hand, is only observed at the surface following a volcanic eruption. It is no different in composition from magma because it is sourced directly from a magma chamber. Besides erupting only at the surface, lava cools quickly because it is exposed to the Earth’s atmosphere (or sometimes ocean!), and we see different igneous rock textures as a consequence. Igneous rocks from magma are coarse-grained or intrusive because they cool slowly, but those from lava are fine-grained, or extrusive.

Melting Solid Rock

Magma and lava contain three components – melt, solids, and volatiles (dissolved gases). The liquid part, called melt, is made of ions from minerals that have already melted.

All you need to melt a solid rock is heat, right? Wrong! Most lava at volcanoes is around 700 to 1300 °C, which is typical of our upper mantle. However, our mantle as a whole is solid, so something else is required to cause rock to melt. That “something else” can be a sudden decrease in pressure or the introduction of liquid water, which will lower the melting point of rocks in the mantle.

Decompression Melting

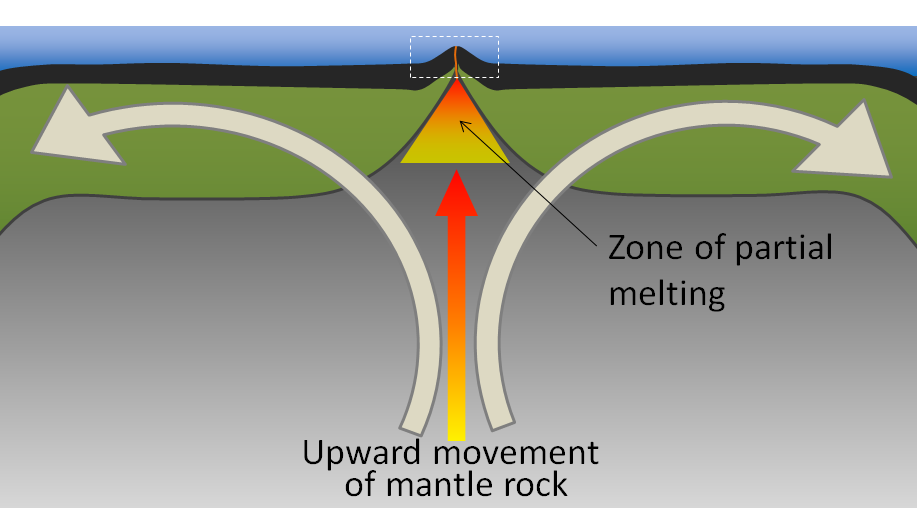

Our mantle is solid, but under high temperatures and pressures, it flows over very long timescales in a process known as convection. Convection forms circular cells of movement for the rock within the mantle, and sometimes leads to the upwelling of hot mantle material at divergent plate boundaries and hot spots.

Rock is a bad conductor of heat, so as rock in the mantle rises with upwelling or convection, its temperature does not significantly change. Nevertheless, when that rock rises, the pressure of the rock does decrease because the depth decreases. When the hot mantle rock does not have sufficiently high pressures to keep itself solid, it starts to melt. This process of the rock melting due to a sudden change in pressure is called decompression melting, and it typically occurs at hot spots and divergent boundaries, such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge [1].

Flux Melting

At subduction zones along the Earth’s lithosphere, the descending slab is always made of oceanic lithosphere. This slab contains some hydrated minerals that when exposed to elevated temperatures and pressures during subduction, will become released as volatile gases such as water vapor.

These volatile gases rise and interact with the overlying plate in the subduction zone. The addition of the volatiles does not change the pressure or temperature of the rock, but it does lower a property called the melting point. The decrease in melting point with those added volatiles suddenly makes it possible for the rocks in the subduction zone to melt at the pressures and temperatures they have been experiencing, which is why we observe volcanoes at this type of plate boundary. Magmas producing the volcanoes of the Ring of Fire, associated with the subduction zones bordering the Pacific Ocean, are a result of flux melting [1].

Magma Composition

The words that describe the composition of igneous rocks also describe magma composition. Mafic magmas are low in silica and have darker magnesium (Mg), and iron (Fe)-rich minerals, such as olivine and pyroxene.

Felsic magmas are higher in silica and have lighter-colored minerals such as quartz and orthoclase feldspar.

The higher the amount of silica in the magma, the higher is its viscosity. Viscosity is a liquid’s resistance to flow or movement within the Earth or on its surface. Viscosity determines what the magma will do. Mafic magma is not very viscous and will flow smoothly to the surface.

***See 4.5 for Text and Media Attributions

molten rock that can be found beneath the Earth's surface.

molten rock that has erupted at the Earth's surface due to volcanic processes.

The solidification of loose sediment materials as solid sedimentary rock through compacting pressures and cementation.

an area on the Earth's surface where lava, ash, and/or volatile gases erupt and eventually solidify into rock.

The process in which gravity and the pressure from overlying layers of rock cause loose sediments to press together.

Image by USGS (Public Domain).

coarse-grained igneous rock texture with visible crystals within the matrix.

Fine-grained, or microcrystalline, igneous rock texture.

The liquid portion of molten rock found in both lava and magma.

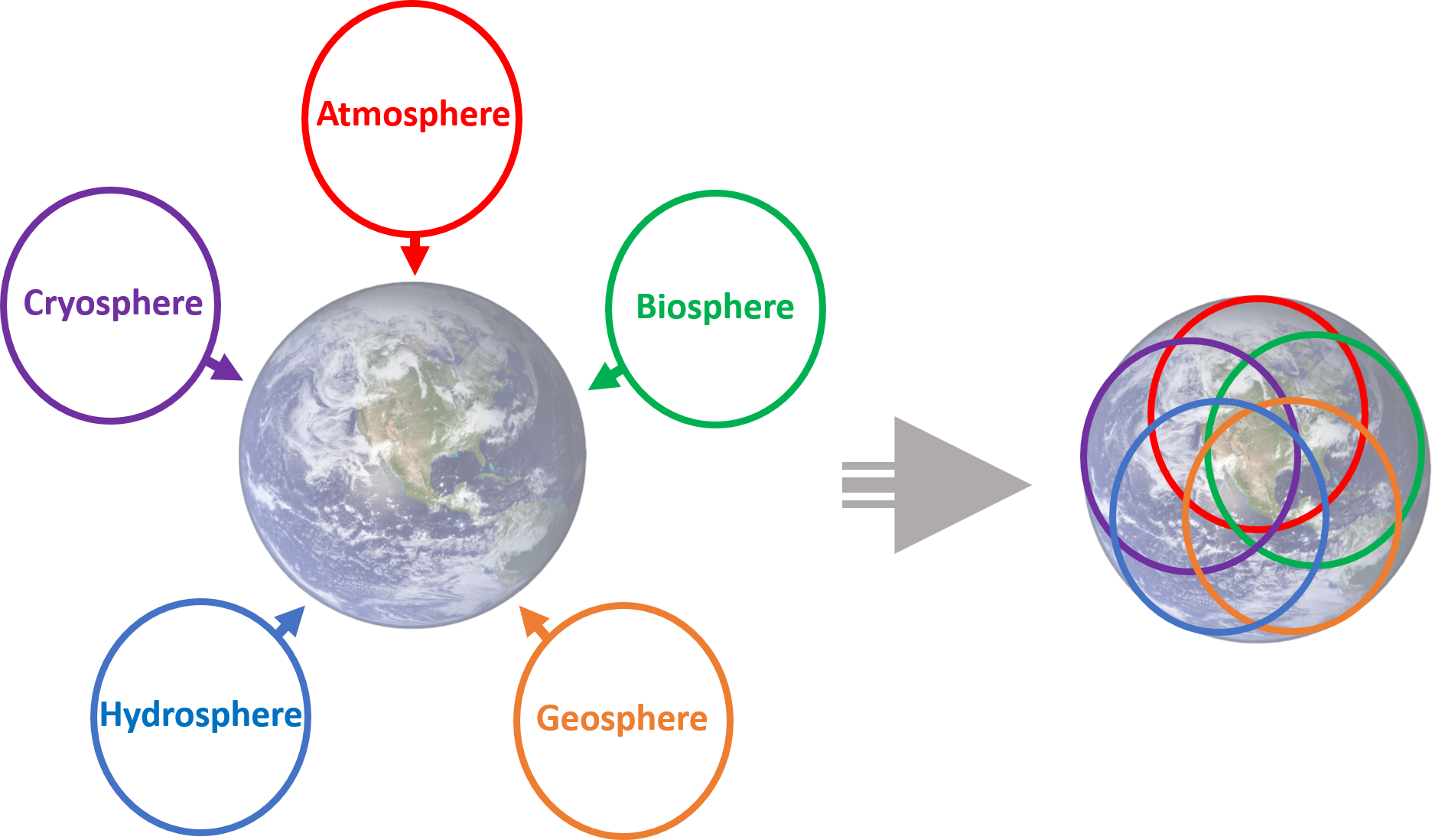

Geology is an umbrella science that encompasses all biological, chemical, and physical processes that act on the planet and make up our world. In the same way that the human body can be divided into systems (circulatory, digestive, endocrine, etc.), the Earth can be described as a complex entity that encompasses many different systems all acting on one another. There are 5 main systems, or spheres, found on Earth: geosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and cryosphere.

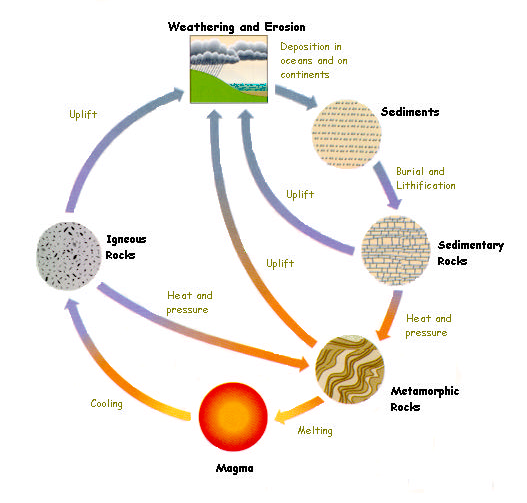

Geosphere ("geo" = Earth)

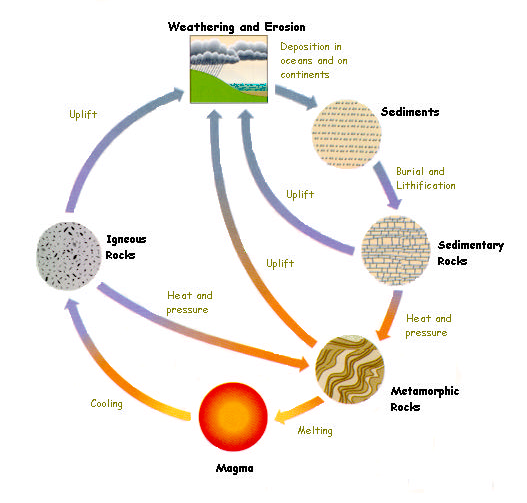

The geosphere encompasses all physical material that makes up the interior and surface of the Earth. This includes all rocks and minerals, but is also includes the active processes that link these rocks and minerals together. While many tend to focus on the three types of rocks: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic, the forces of plate tectonics and weathering actively change rocks from one type to another. This system is referred to as the Rock Cycle. This is the focus of most physical geology courses and will be the main framework for this text. Because the geosphere describes the physical structure of the Earth, it is integral to all other spheres as well.

Biosphere ("bio" = life)

The biosphere is made up of all living things, as well as the ecosystems that support that life. Obviously, life can be found in many different places, from the tops of mountains to the bottoms of oceans, in wet and dry places, in cold and hot environments. The biosphere therefore overlaps and interacts with all other spheres.

Hydrosphere ("hydro" = water)

The Earth has been described as the “Blue Marble” in space due to the presence of enormous amounts of water on its surface. All of the liquid water found on earth makes up the hydrosphere. As water flows on the Earth’s surface, it changes landscapes and nourishes life, and interacts with all other spheres.

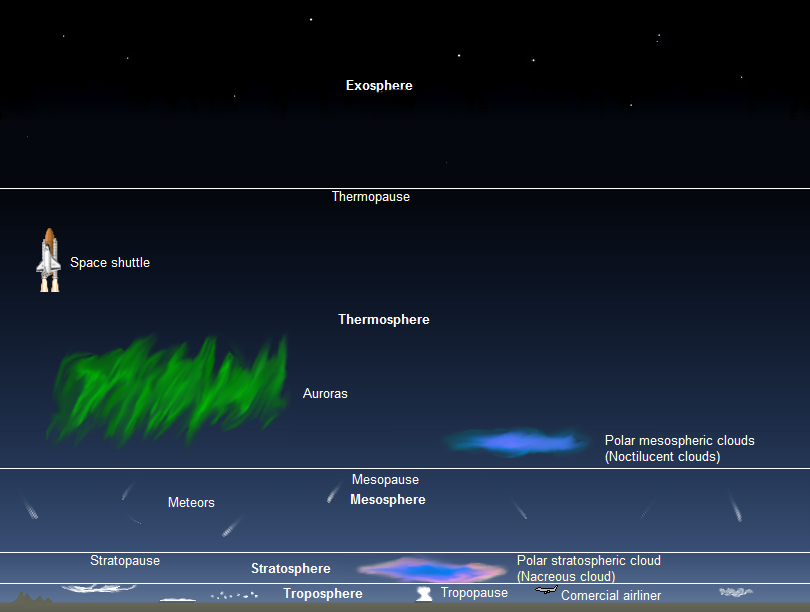

Atmosphere ("atmo" = vapor)

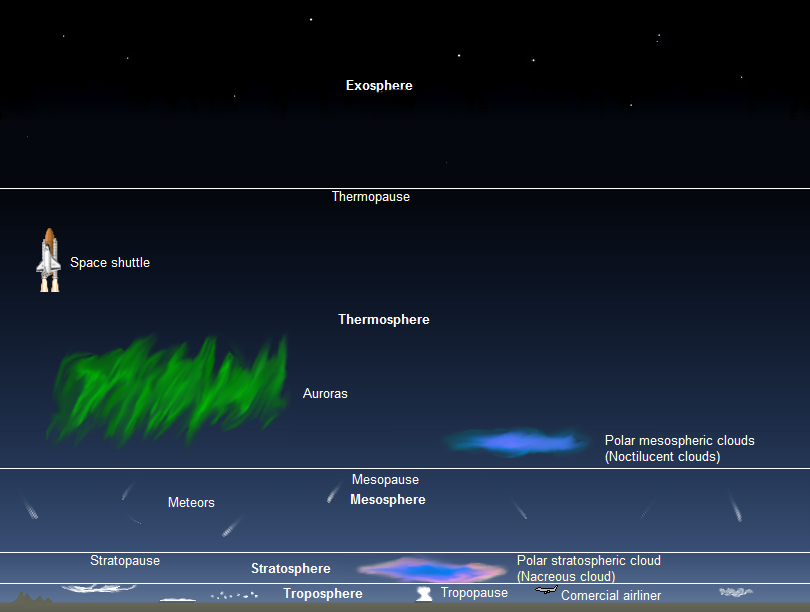

All of the gases that circulate around and surround the earth are a part of the atmosphere. This includes the air we breathe, the gases that are responsible for global weather and climate, as well as the ones that burn up meteorites as they plummet toward the Earth’s surface. The atmosphere is further broken into layers: troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere.

Cryosphere ("cryo" = frozen)

Cryo- comes from a Greek word meaning "frost." The cryosphere encompasses all of frozen water on the Earth. Typically found at high elevations and at the poles, ice can have dramatic impacts on landscapes (geosphere), provide sources of liquid water (hydrosphere), and support ecosystems for living things (biosphere).

Integrated systems

While it is easier to look at each system independently, they are all integrated on the Earth. Each one is constantly acting and interacting with another on our dynamic planet.

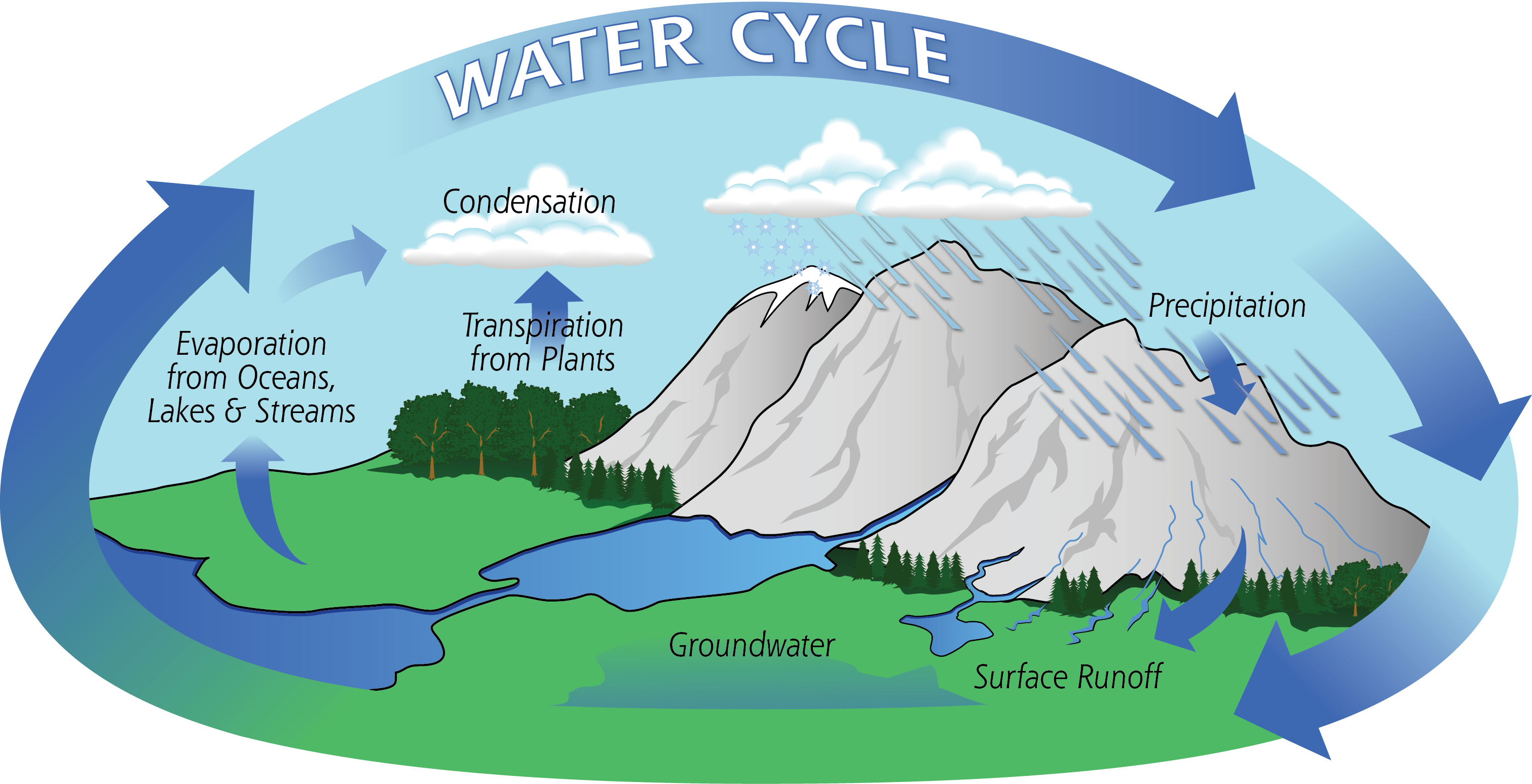

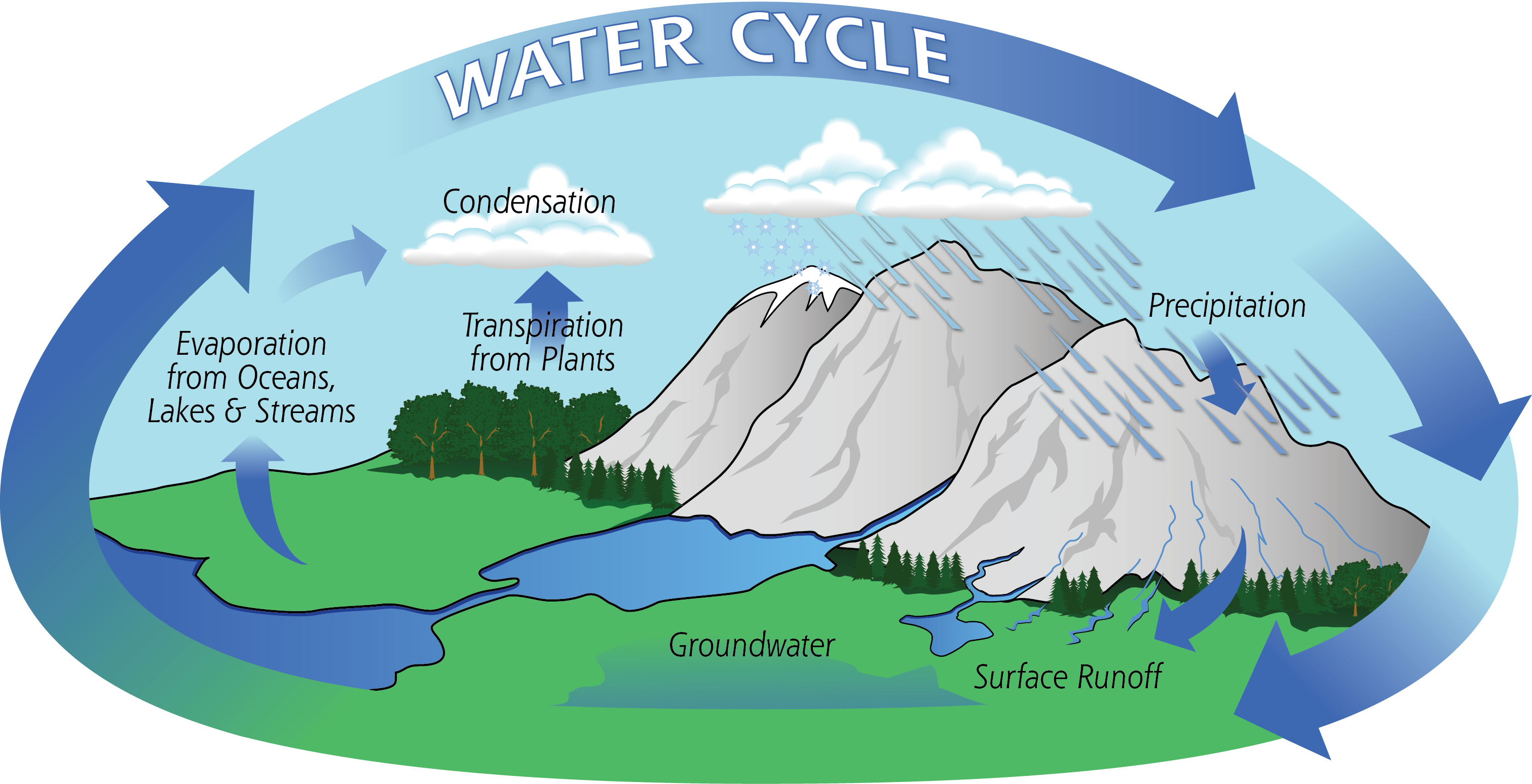

H2O, or the water molecule, is constantly changing. It is the only substance on Earth that is present in all states of matter - solid, liquid, and gas. The cycling of water throughout the Earth, also called the hydrologic cycle, describes how water moves through various environments on Earth. The largest reservoir of water is in the ocean, and it exists there as a liquid. Through the process of evaporation, it becomes a gas. At that point, it may crystallize as a solid (snow or ice) and deposit on land. It could then melt, forming a liquid again, and run off the landforms, eternally shaping the Earth. It can be taken up into plants, aiding in photosynthesis, and released as a gas through the process of transpiration. The possibilities of pathways for water to travel on Earth are endless.

Backyard Geology: Spheres intersect for one of the 7 Natural Wonders of the World

Backyard Geology: Spheres intersect for one of the 7 Natural Wonders of the World

Arizona is known as the "Grand Canyon State" because of the dramatic landscape that unfolds at the intersection of brightly colored flat-lying sedimentary rocks and a dynamic river system. This landscape evolved over millions of years while the underlying rocks were uplifted by Plate Tectonics, and the Colorado River cut down through soft sedimentary rocks..

Volcanic Hazards

Volcanoes are responsible for a large number of deaths, but lava is not the only danger associated with these hazards. Mount Vesuvius (Naples, Italy) is infamous for its violent explosion thousands of years ago in 79 AD when a pyroclastic flow travelled over the Roman countryside and engulfed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum [1]. It was not until the 18th century that we uncovered the shocking remains of these towns beneath over 10 feet of ash and the casts of people preserved within it.

We know more about volcanic hazards over the past century because they have been better monitored and documented. We have seen enormously violent explosions, effusive lava, fast pyroclastic flows, ash, landslides, toxic gases, and more!

Pyroclastic Flows

The most dangerous type of volcanic hazard are pyroclastic flows. These flows are a mix of lava blocks, pumice, ash, and hot gases between 400 to 1,300°F! The turbulent cloud of ash and gas races down the steep flanks at high speeds at an average of 60 mph (much faster than people can run) into the valleys where farmlands grow and cities thrive [1].

Pyroclastic flows can often be expected of stratovolcanoes that contain felsic or intermediate magma. This magma is silica-rich and contains volatile gases that make it highly viscous. Therefore, these volcanoes often have very violent eruptions that are accompanied by a pyroclastic flow.

There are numerous examples of deadly pyroclastic flows. In 2014, the Mount Ontake pyroclastic flow in Japan killed 47 people. The flow was caused by magma heating groundwater into steam, which then rapidly ejected with ash and volcanic bombs. Some were killed by inhalation of toxic gases and hot ash, while volcanic bombs struck others [1]. In 1902, on the Caribbean Island Martinique, Mount Pelee erupted with a violent pyroclastic flow that destroyed the entire town of St. Pierre and killing 28,000 people in moments [3].

Lahars

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9080YePWKY

A lahar is an Indonesian word for a mudflow that is a mixture of water, ash, rock fragments, and other debris that moves down the mountainside of a volcano (or other nearby mountains covered with freshly-erupted ash). They form from the rapid melting of snow or glaciers on volcanoes or sometimes in combination with a new eruption and heavy thunderstorm, as seen at Mt. Pinatubo.

Lahars move like a slurry of concrete, but they can move extremely fast at speeds up to 50 mph. Part of the reason they are so deadly is because they are slurry-like; they easily capture materials in their wake and they can travel very long distances like a flash flood [1].

During the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption, lahars reached 17-miles (27 km) down the North Fork of the Toutle River. Another scenario played out when a lahar from the volcano Nevado del Ruiz Colombia, buried a town in 1985 and killed an estimated 25,000 people [1].

Tephra and Ash

Volcanoes—mainly stratovolcanoes—eject substantial amounts of tephra and ash [1].

Tephra is heavier than ash, so it will fall closer to the volcano's crater and vent. Large masses of tephra sometimes erupt from volcanoes and can pose deadly hazards to anyone nearby. These are called volcanic bombs [1].

Ash is much finer, but it should not be underestimated. It can be carried much longer distances away from the volcano, and that can cause more widespread issues in nearby towns and cities. A build-up of ash can collapse the roof of a building or home, and the microscopic minerals within ash will cause respiratory illnesses such as silicosis. Inhaling ash is extremely hazardous because much of it contains microscopic volcanic glass particles [4]. Imagine inhaling tiny shards of glass!

Ash will also interfere with transportation services farther away from an eruption. For example, the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption in Iceland created a gigantic ash cloud that caused a significant air travel disruption in northern Europe. No one was hurt, but the cost to the world economy was estimated to be billions of dollars [3].

Volcanic Gases

Magma contains dissolved volatile gases. As magma rises toward the surface, the pressure that keeps it in

the magma chamber will start to decrease, which allows those gases to escape. Think of this process like twisting the cap of a soda bottle; the first thing to rise and escape in that initial hissing noise is gas [1]!

The types of gases that are commonly released from volcanoes include greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), methane (CH4), and water vapor (H2O). There are also toxic and acidic gases present at volcanoes such as HF, HBr, and HCl. After gigantic volcanic explosions, some volcanic gases such as sulfur dioxide will become sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere. These aerosol particles block sunlight coming toward Earth's surface and cause the planet to become cooler [5].

The volcanic gases can be both toxic and suffocating, and these gases sometimes are released from a volcano without an accompanying eruption. Gases were released from the Oku Volcanic Plain in Lake Nyos, Cameroon, and the carbon dioxide suffocated almost 2,000 people in 1986 [1].

One of two or more species of the same chemical element, i.e., having the same number of protons in the nucleus, but differing from one another by having a different number of neturons

the temperature and pressure required for a solid material to melt into a liquid.

movement driven by density and heat in which low-density hot materials move upward and dense, cold materials sink downward.

Fine particles, liquid droplets, or gases that are ejected into the atmosphere by man-made pollution or volcanic eruptions. Aerosols have the ability to reflect sunlight back toward space and cause the planet to experience colder temperatures.

Geology is an umbrella science that encompasses all biological, chemical, and physical processes that act on the planet and make up our world. In the same way that the human body can be divided into systems (circulatory, digestive, endocrine, etc.), the Earth can be described as a complex entity that encompasses many different systems all acting on one another. There are 5 main systems, or spheres, found on Earth: geosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and cryosphere.

Geosphere ("geo" = Earth)

The geosphere encompasses all physical material that makes up the interior and surface of the Earth. This includes all rocks and minerals, but is also includes the active processes that link these rocks and minerals together. While many tend to focus on the three types of rocks: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic, the forces of plate tectonics and weathering actively change rocks from one type to another. This system is referred to as the Rock Cycle. This is the focus of most physical geology courses and will be the main framework for this text. Because the geosphere describes the physical structure of the Earth, it is integral to all other spheres as well.

Biosphere ("bio" = life)

The biosphere is made up of all living things, as well as the ecosystems that support that life. Obviously, life can be found in many different places, from the tops of mountains to the bottoms of oceans, in wet and dry places, in cold and hot environments. The biosphere therefore overlaps and interacts with all other spheres.

Hydrosphere ("hydro" = water)

The Earth has been described as the “Blue Marble” in space due to the presence of enormous amounts of water on its surface. All of the liquid water found on earth makes up the hydrosphere. As water flows on the Earth’s surface, it changes landscapes and nourishes life, and interacts with all other spheres.

Atmosphere ("atmo" = vapor)

All of the gases that circulate around and surround the earth are a part of the atmosphere. This includes the air we breathe, the gases that are responsible for global weather and climate, as well as the ones that burn up meteorites as they plummet toward the Earth’s surface. The atmosphere is further broken into layers: troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere.

Cryosphere ("cryo" = frozen)

Cryo- comes from a Greek word meaning "frost." The cryosphere encompasses all of frozen water on the Earth. Typically found at high elevations and at the poles, ice can have dramatic impacts on landscapes (geosphere), provide sources of liquid water (hydrosphere), and support ecosystems for living things (biosphere).

Integrated systems

While it is easier to look at each system independently, they are all integrated on the Earth. Each one is constantly acting and interacting with another on our dynamic planet.

H2O, or the water molecule, is constantly changing. It is the only substance on Earth that is present in all states of matter - solid, liquid, and gas. The cycling of water throughout the Earth, also called the hydrologic cycle, describes how water moves through various environments on Earth. The largest reservoir of water is in the ocean, and it exists there as a liquid. Through the process of evaporation, it becomes a gas. At that point, it may crystallize as a solid (snow or ice) and deposit on land. It could then melt, forming a liquid again, and run off the landforms, eternally shaping the Earth. It can be taken up into plants, aiding in photosynthesis, and released as a gas through the process of transpiration. The possibilities of pathways for water to travel on Earth are endless.

Backyard Geology: Spheres intersect for one of the 7 Natural Wonders of the World

Backyard Geology: Spheres intersect for one of the 7 Natural Wonders of the World

Arizona is known as the "Grand Canyon State" because of the dramatic landscape that unfolds at the intersection of brightly colored flat-lying sedimentary rocks and a dynamic river system. This landscape evolved over millions of years while the underlying rocks were uplifted by Plate Tectonics, and the Colorado River cut down through soft sedimentary rocks..

***See 1.5 for Text and Media Attributions

The process in which solid rock melts upon experiencing a sudden decrease in pressure, but not temperature.

The world's longest mountain chain found beneath the Atlantic ocean between North America, South America and Europe and Africa. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is an example of a mid-ocean ridge, or MOR.

The world's greatest Mass Extinction event that occurred around 252 million years ago and resulted in the loss of 95% of ocean life and 70% of life on land.

Image by James St. John (Flickr), CC BY 2.0

The graph resulting from measurements of a seismograph

Gases dissolved within magma or lava.

a process in which solid rock melts because volatiles such as water vapor have caused its melting point to decrease.

Originating from an iron and magnesium-rich magma/lava composition.

Time is the dimension that sets geology apart from most other sciences. Geological time is vast, and Earth has changed enough over that time that some of the rock types that formed in the past could not form today. Furthermore, as we’ve discussed, even though most geological processes are very, very slow, the vast amount of time that has passed has allowed for the formation of extraordinary geological features, as shown in Figure 8.0.1.

We have numerous ways of measuring geological time. We can tell the relative ages of rocks (for example, whether one rock is older than another) based on their spatial relationships; we can use fossils to date sedimentary rocks because we have a detailed record of the evolution of life on Earth; and we can use a range of isotopic techniques to determine the actual ages (in millions of years) of igneous and metamorphic rocks.

But just because we can measure geological time doesn’t mean that we understand it. One of the biggest hurdles faced by geology students—and geologists as well—in mastering geology, is to really come to grips with the slow rates at which geological processes happen and the vast amount of time involved.\

Learning Objectives

After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to:

- Apply basic geological principles to the determination of the relative ages of rocks.

- Explain the difference between relative and absolute age-dating techniques.

- Summarize the history of the geological time scale and the relationships between eons, eras, periods, and epochs.

- Understand the importance and significance of unconformities.

- Estimate the age of a rock based on the fossils that it contains.

- Describe some applications and limitations of isotopic techniques for geological dating.

- Use isotopic data to estimate the age of a rock.

- Describe the techniques for dating geological materials using tree rings and magnetic data.

- Explain why an understanding of geological time is critical to both geologists and the public in general.

Media Attributions

- © Steven Earle. CC BY.

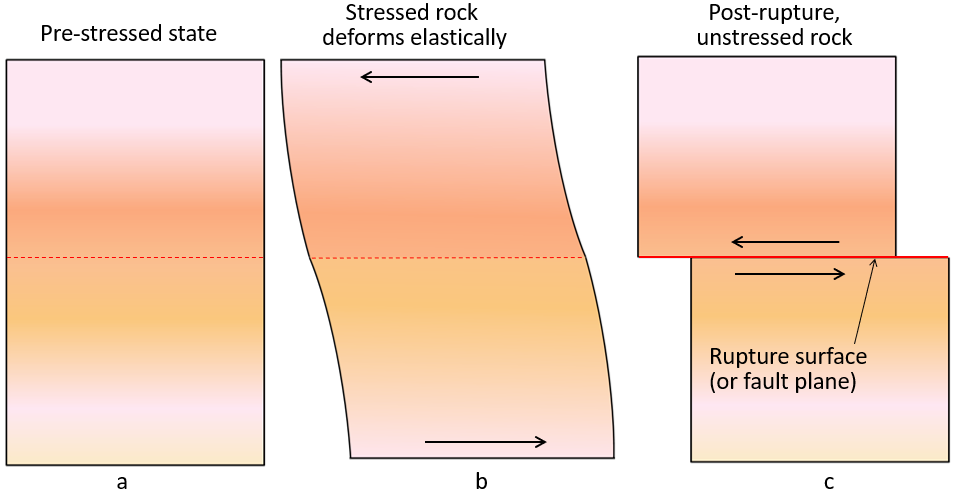

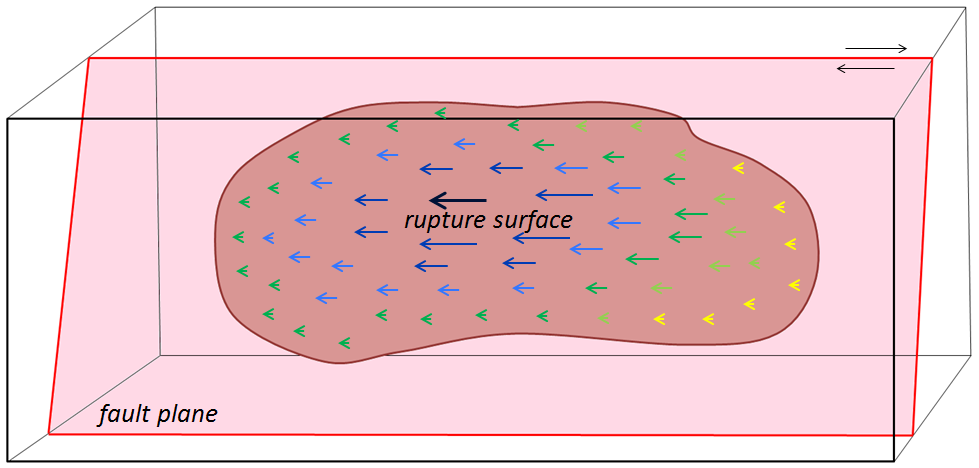

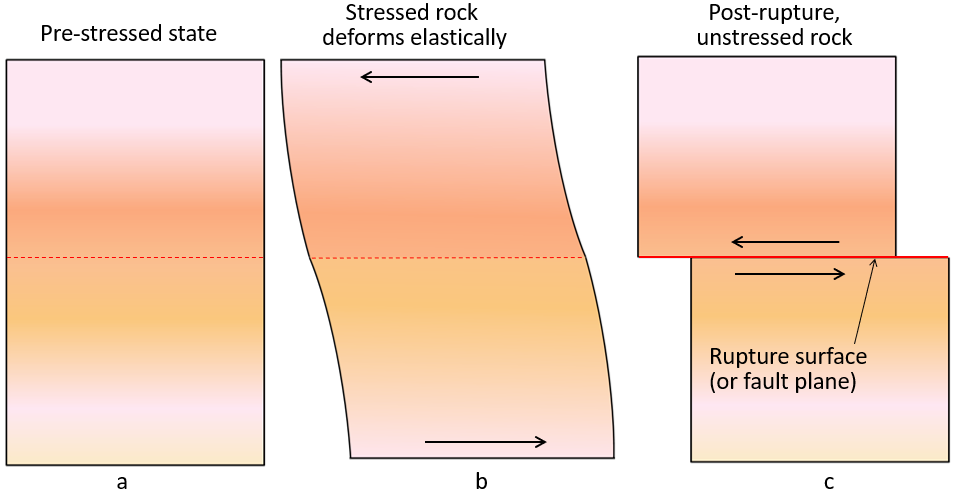

An earthquake is defined as the shaking of the ground, due to movements in the Earth's crust. The movements, usually caused by plate tectonics, apply stress to rocks, which initially cause the rocks to deform elastically, storing the stress. Once enough stress is applied, the rocks will rupture (break) and release the stored energy, causing an earthquake. Most earthquakes are confined to plate boundaries, but earthquakes can also occur from volcanic activity or within a tectonic plate. The shifting and displacement occurs along the rupture surface, also referred to as a fault plane. The line where the fault plane intersects the Earth's surface is called a fault or fault scarp. All earthquakes cause a rupture surface, but not all of them can be seen as a fault at the surface.

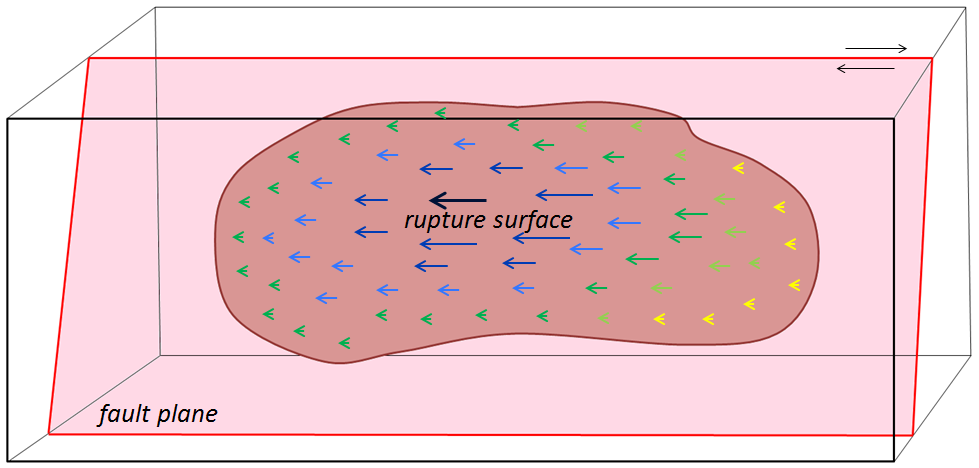

Rupture Surface

The concept of a rupture surface is illustrated below (Fig. 10.1.2). An earthquake does not happen at a single point, it happens over an extended area. It also doesn't happen all at one time! The extent of a rupture surface and the amount of displacement will depend on a number of factors, including the type and strength of the rock, and the degree to which it was stressed or altered beforehand.

Foreshocks and Aftershocks

Foreshocks are small earthquakes that precede a larger event. As previously mentioned, hundreds of thousands of earthquakes occur yearly as plates release stress and rupture, not all of these are foreshocks. In order to be considered a foreshock, a larger event must occur in the same area. Special attention is paid to swarms (groupings) of foreshocks in an area, as they may signify a larger event will occur. Aftershocks are also earthquakes, but they have been triggered by stress transfer from a preceding earthquake and they occur within the original rupture surface.

Aftershocks can be of any magnitude, but most are smaller than the earthquake that triggered them. Many aftershocks occur within seconds or minutes of the main shock, but they can occur over days, weeks, months, or years. Figure 10.1.4 shows the distribution of aftershocks within the first 4 days of the devastating 9.0 earthquake of 2011 in Japan. The large yellow circle is the main earthquake event, and the rest of the circles represent aftershocks in the area of the fault. Though the main earthquake released a tremendous amount of energy and released stress on that part of the fault, a resulting increase in stress on nearby parts of the fault contributed to the multiple aftershocks. Hundreds of aftershocks were recorded within a few days, and thousands have occurred since the original quake event.

Stress Transfer

As already noted, aftershocks are related to stress transfer. For example, the main shock of the 9.0 earthquake in Japan in 2011 triggered aftershocks in the immediate area, which triggered more in the surrounding area, eventually extending along the fault plane in all directions. The earthquake, inclusive of aftershocks, also changed the stress on adjacent parts of the fault zone. Though the aftershocks all occur on the original rupture surface, stress transfer isn’t necessarily restricted to the fault along which an earthquake happened. It can affect the rocks around the site of the earthquake and may lead to increased stress on other faults in the region. The effects of stress transfer don’t necessarily show up right away. Segments of faults are typically in some state of stress, and the transfer of stress from another area is only rarely enough to push a fault segment beyond its limits to the point of rupture. The stress that is added by stress transfer accumulates along with the ongoing buildup of stress from plate motion and eventually leads to another earthquake (1).

Digging Deeper: Earthquakes only occur on Earth!

Really, we're talking about the concept of "quakes" - the release of stored energy due to the movement of rocks. They are only "Earthquakes" because they occur on Earth.

- Moonquakes occur, and were first detected by the Apollo astronauts. Scientists believe that they are generated by the shrinking of the Moon. As the interior cools, the Moon shrinks, causing small ruptures to occur and quakes to be generated. Faults can bee seen on the surface of the moon!

- Marsquakes have also been detected by NASA scientists! With more advancing missions to Mars, future marsquakes will become more intensively studied. Mars has had active volcanism in its past, and is thought to have a molten core, which may account for the quakes.

Hazards

Earthquakes generate a multitude of associated hazards. Some are related to the underlying geology of the area and intensity and duration of shaking, while others are made worse by human built structures. Some are a combination of effects.

Shaking Intensity, Duration, and Underlying Geology

It seems intuitive, but more significant shaking and duration of shaking will cause more destruction than less shaking and shorter shaking. In addition, intensity can be affected by resonance. Resonance is when the frequency of seismic energy matches a building's natural frequency of shaking, determined by properties of the building, and intensifies the shaking's amplitude. This famously happened in the 1985 Mexico City Earthquake, where buildings of heights between 6 and 15 stories were especially vulnerable to earthquake damage. Skyscrapers designed with earthquake resilience have dampers, and base isolation features to reduce resonance. Changes in the structural integrity of a structure could alter its resonance. Conversely, changes in measured resonance can indicate potential changes in structural integrity. (4)

Amplification can also occur depending on the material in the subsurface (Figure 10.4.1). Amplification refers to the levels of shaking that may be increased by softness of the surface rocks, topography, and thickness of surface sediments. The image below shows the potential amplification predicted in the Los Angeles region.

Another good example of this is in the Oakland area near San Francisco, where parts of a two-layer highway built on soft sediments collapsed during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake (Fig. 10.4.2). At least two properties of the Earth's crust conspired to cause this collapse: it was built on loose soils that shook much more strongly than surrounding regions on stronger ground, and variations in the thickness of the Earth's crust between the epicenter of the Loma Prieta earthquake in the Santa Cruz Mountains and Oakland actually focused energy toward Oakland and downtown San Francisco. (1)

Building Design

Building damage is also greatest in areas of soft sediments, and multi-story buildings tend to be more seriously damaged than smaller ones. Buildings can be designed to withstand most earthquakes, and this practice is increasingly applied in earthquake-prone regions. Turkey is one such region, and even though Turkey had a relatively strong building code in the 1990s, adherence to the code was poor, as builders did whatever they could to save costs, including using inappropriate materials in concrete and reducing the amount of steel reinforcing (Figure 10.4.4). The result was that there were over 17,000 deaths in the 1999 M7.6 Izmit earthquake. After two devastating earthquakes that year, Turkish authorities strengthened the building code further, but the new code has been applied only in a few regions, and enforcement of the code is still weak, as revealed by the amount of damage from a M7.1 earthquake in eastern Turkey in 2011. (1)

Fires

Fires are commonly associated with earthquakes because fuel pipelines rupture and electrical lines are damaged when the ground shakes. Most of the damage in the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake was caused by massive fires in the downtown area of the city. Some 25,000 buildings were destroyed by those fires, which were fuelled by broken gas pipes. Fighting the fires was difficult because water mains had also ruptured. The risk of fires can be reduced through P-wave early warning systems if utility operators can reduce pipeline pressure and close electrical circuits. (1)

Landslides

Landslides by themselves are a major geologic hazard, since they are widespread. Earthquakes are important triggers for failures on slopes that are already weak. An example is the Las Colinas slide in the city of Santa Tecla, El Salvador, which was triggered by a M7.6 offshore earthquake in January 2001 (Fig. 10.4.6). This is just one of many hundreds of slope failures that resulted from that earthquake. Over 500 people died in the area affected by this slide. (1)

Liquefaction

Ground shaking during an earthquake can be enough to weaken rock and unconsolidated materials to the point of failure, but in many cases the shaking also contributes to a process known as liquefaction in which an otherwise solid body of sediment is transformed into a liquid mass that can flow. When water-saturated sediments are shaken, the grains become rearranged to the point where they are no longer supporting one another. Instead, the water between the grains is holding them apart and the material can flow. Liquefaction can lead to the collapse of buildings and other structures that might be otherwise undamaged. A good example is the collapse of apartment buildings during the 1964 Niigata earthquake (M7.6) in Japan (Fig. 10.4.7). Liquefaction can also contribute to slope failures and to fountains of sandy mud (sand volcanoes) in areas where there is loose saturated sand beneath a layer of more cohesive clay. (1)

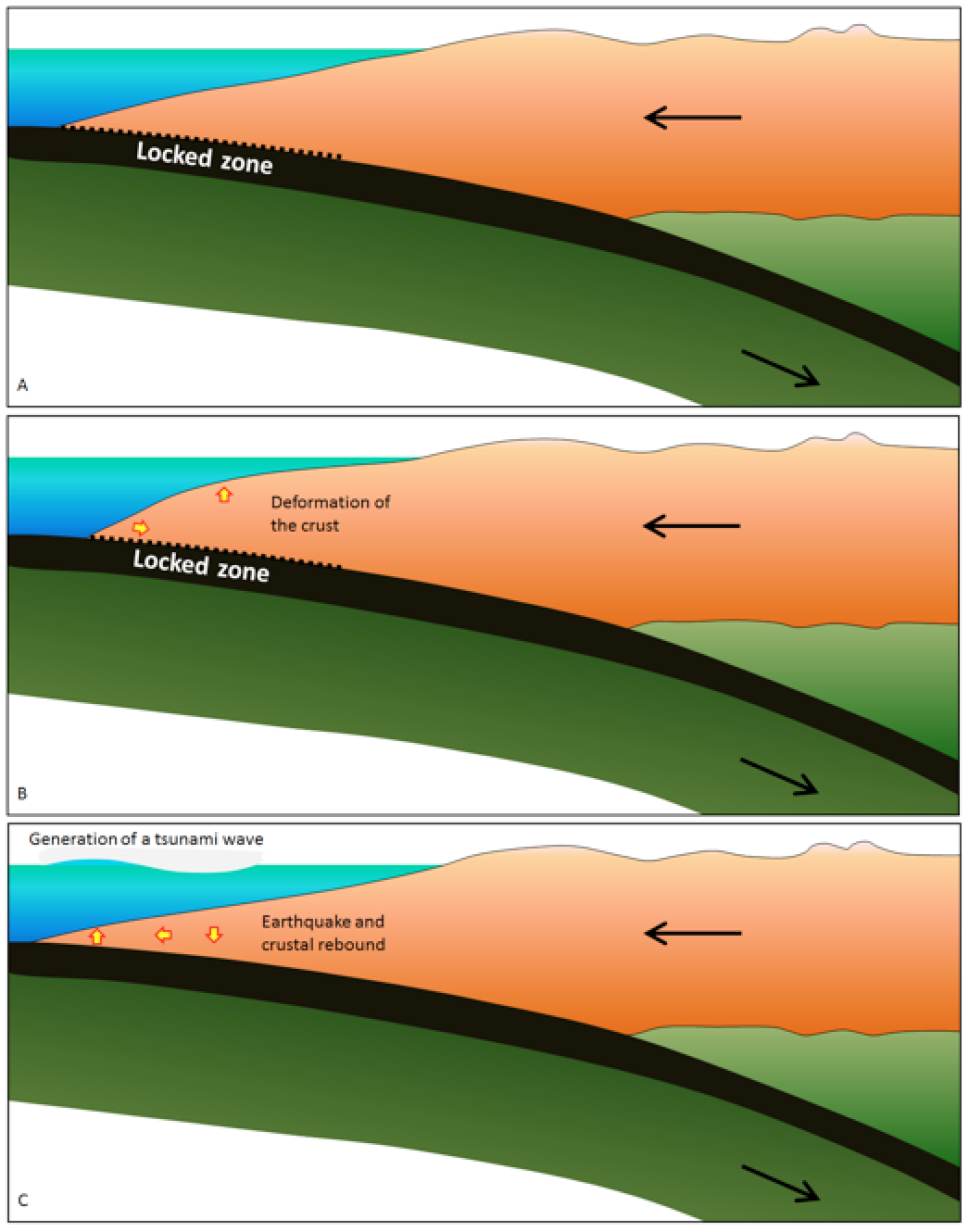

Tsunami

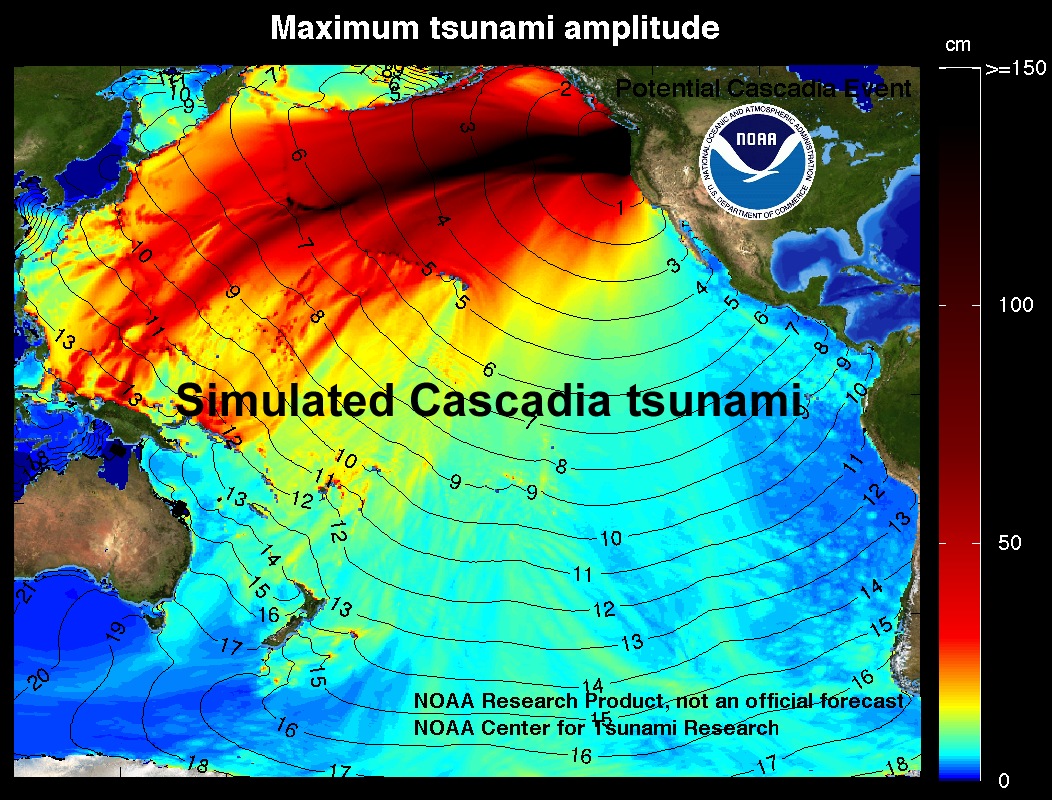

Earthquakes that take place beneath the ocean have the potential to generate tsunami. The most likely situation for a significant tsunami is a large (M7 or greater) subduction-related earthquake, because the seafloor is dramatically moved. As shown in Figure 10.4.8, during the time between earthquakes the overriding plate becomes distorted by elastic deformation; it is squeezed laterally and pushed up. When an earthquake happens, the plate rebounds and there is both uplift and subsidence on the sea floor, in some cases by as much as several meters vertically over an area of thousands of square kilometers. This vertical motion is transmitted through the water column where it generates a series of waves that then spread across the ocean. Subduction earthquakes with magnitude less than 7 do not typically generate significant tsunami because the amount of vertical displacement of the sea floor is minimal. Sea-floor transform earthquakes, even large ones (M7 to M8), don’t typically generate tsunami either, because the motion is mostly side to side, not vertical. (1) While tsunami can affect any coastal region, they are much more likely in areas with subduction zones, like the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Tsunami waves travel at velocities of several hundred kilometers per hour and easily make it to the far side of an ocean in about the same time as a passenger jet. The simulated one shown in Figure 10.4.9 is similar to that created by the 1700 Cascadia earthquake off the coast of British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, which was recorded in Japan nine hours later. (1)

Risk

Earthquakes cause a lot of damage. This damage can include structural damage to buildings, fires, damage to bridges, highways, pipelines and electrical transmission lines, initiation of slope failures, liquefaction, and tsunami. The types of impacts depend to a large degree on where the earthquake is located: whether it is predominantly urban or rural, densely or sparsely populated, highly developed or underdeveloped, and of course on the ability of the infrastructure to withstand shaking.

The map above (Fig. 10.1.10) shows the potential earthquake hazards in the United States of America based on the size of the earthquake and potential frequency. As we have discussed, a geologic hazard, is the potential for loss or damage. However, the risk can vary related to population and infrastructure, as well as other factors, of the place where the hazard occurs. We will focus on the geologic hazards in general, but it is important to remember the context in which the hazard occurs.

originating from a feldspar and silica-rich magma/lava composition.

Image by GeoPotinga (Wikimedia Commons), CC BY-SA 4.0

An earthquake is defined as the shaking of the ground, due to movements in the Earth's crust. The movements, usually caused by plate tectonics, apply stress to rocks, which initially cause the rocks to deform elastically, storing the stress. Once enough stress is applied, the rocks will rupture (break) and release the stored energy, causing an earthquake. Most earthquakes are confined to plate boundaries, but earthquakes can also occur from volcanic activity or within a tectonic plate. The shifting and displacement occurs along the rupture surface, also referred to as a fault plane. The line where the fault plane intersects the Earth's surface is called a fault or fault scarp. All earthquakes cause a rupture surface, but not all of them can be seen as a fault at the surface.

Rupture Surface

The concept of a rupture surface is illustrated below (Fig. 10.1.2). An earthquake does not happen at a single point, it happens over an extended area. It also doesn't happen all at one time! The extent of a rupture surface and the amount of displacement will depend on a number of factors, including the type and strength of the rock, and the degree to which it was stressed or altered beforehand.

Foreshocks and Aftershocks

Foreshocks are small earthquakes that precede a larger event. As previously mentioned, hundreds of thousands of earthquakes occur yearly as plates release stress and rupture, not all of these are foreshocks. In order to be considered a foreshock, a larger event must occur in the same area. Special attention is paid to swarms (groupings) of foreshocks in an area, as they may signify a larger event will occur. Aftershocks are also earthquakes, but they have been triggered by stress transfer from a preceding earthquake and they occur within the original rupture surface.

Aftershocks can be of any magnitude, but most are smaller than the earthquake that triggered them. Many aftershocks occur within seconds or minutes of the main shock, but they can occur over days, weeks, months, or years. Figure 10.1.4 shows the distribution of aftershocks within the first 4 days of the devastating 9.0 earthquake of 2011 in Japan. The large yellow circle is the main earthquake event, and the rest of the circles represent aftershocks in the area of the fault. Though the main earthquake released a tremendous amount of energy and released stress on that part of the fault, a resulting increase in stress on nearby parts of the fault contributed to the multiple aftershocks. Hundreds of aftershocks were recorded within a few days, and thousands have occurred since the original quake event.

Stress Transfer

As already noted, aftershocks are related to stress transfer. For example, the main shock of the 9.0 earthquake in Japan in 2011 triggered aftershocks in the immediate area, which triggered more in the surrounding area, eventually extending along the fault plane in all directions. The earthquake, inclusive of aftershocks, also changed the stress on adjacent parts of the fault zone. Though the aftershocks all occur on the original rupture surface, stress transfer isn’t necessarily restricted to the fault along which an earthquake happened. It can affect the rocks around the site of the earthquake and may lead to increased stress on other faults in the region. The effects of stress transfer don’t necessarily show up right away. Segments of faults are typically in some state of stress, and the transfer of stress from another area is only rarely enough to push a fault segment beyond its limits to the point of rupture. The stress that is added by stress transfer accumulates along with the ongoing buildup of stress from plate motion and eventually leads to another earthquake (5).

Digging Deeper: Earthquakes only occur on Earth!

Really, we're talking about the concept of "quakes" - the release of stored energy due to the movement of rocks. They are only "Earthquakes" because they occur on Earth.

- Moonquakes occur, and were first detected by the Apollo astronauts. Scientists believe that they are generated by the shrinking of the Moon. As the interior cools, the Moon shrinks, causing small ruptures to occur and quakes to be generated. Faults can bee seen on the surface of the moon!

- Marsquakes have also been detected by NASA scientists! With more advancing missions to Mars, future marsquakes will become more intensively studied. Mars has had active volcanism in its past, and is thought to have a molten core, which may account for the quakes.

a liquid's resistance to flow or movement