2.1 Alfred Wegener and the Strange Idea of Drifting Continents

Our “Contracting Earth”?

How can we explain the movement of land around us over long periods of time? Sometimes volcanoes spring up when there were previously none. Other times, the ground shakes in certain places. Some areas, like Arizona, are home to amazing mountain ranges and valleys, and others are island destinations. How did we make sense of any of this?

Science is an evolving thing, which means that scientists don’t always get it right. Case in point: up until the mid-1900s we believed our planet formed all its breath-taking features by “squeezing” them out! These scientists rightly believed that Earth was a ball of hot, molten material when it first formed in space. Where they went wrong, however, is the belief that the cooling outer shell, contracted like a dried-out raisin [1].

Furthermore, these scientists thought that new landscapes formed through a process called isostasy. This process involved the continents and ocean basins sinking and rising up as they experienced changes in density [1].

Continental Drift

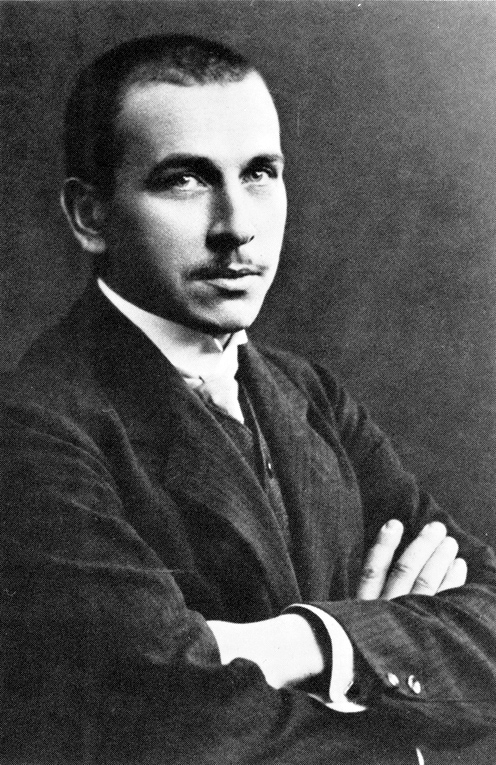

Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) was a German scientist who specialized in meteorology and climatology. He enjoyed field work in Greenland to establish weather monitoring stations and made great contributions to climatology. However, as an avid explorer of the planet, he had something to say about how it operated. In 1910, he publicly disagreed with the extent that the role of isostasy played in the Contracting Earth hypothesis. He furthermore noticed some patterns in our world map that led him to propose a radical counter-hypothesis: the concept of Continental Drift. [2]

Ever since the first world map, people have noticed the similarities between the coastlines of South America and Africa. Would it be such a stretch to imagine these continents being pushed together like two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle? Indeed, what if all of the continents were once merged together at one point as a single landmass, and they broke apart for some reason?

The idea that South America and Africa were once attached as a single landmass was not a new one; Antonio Snider-Pellegrini even did preliminary work on continental separation and matched fossils between the two continents in 1858 [2]. But Wegener’s contribution to this idea was new and interesting in that he collected a tremendous amount of data on these two continents. Let’s review some of this evidence below!

Fossils

The fossils of the ancient life that existed hundreds of millions of years ago have been found along the separate coastlines of not just Africa and South America, but also India, Australia, and Antarctica (see left figure)! These organisms appeared to be exactly the same, but how could they have lived on separate continents? For example, neither the reptile Mesosaurus nor Cynognathus, which were found in South America and Africa could live in salty ocean water. Therefore, Wegener argued, these animals could not have crossed the ocean to live on the continents if they were always separated. That meant that at one time, the continents had to have been merged together as a single landmass!

Those that disagreed with Wegener’s hypothesis made this counter argument: perhaps the continents were in the same configurations hundreds of millions of years ago as they are today. Instead of swimming across deep oceans, these ancient reptiles might have traveled between the continents on narrow land bridges that stretched across the oceans [1]. The only reason we don’t see these land bridges today is because they have sunk down or eroded away.

Which idea makes more sense to you: the continents once being merged together OR the idea of ancient land bridges? Science is about a healthy debate given data and evidence, but Wegener was not done!

Geologic Evidence

Even if ancient reptiles and animals crossed the oceans on land bridges, as Wegener’s opponents argued, there was something that they could not explain: the Geologic Record.

Think of a volcanic eruption, a landslide, a winding river, or a sandy beach. When a layer of rock is deposited, it reflects an environment or event that has happened in the area. Each layer of rock is like a page in a book that each of us can learn to read. Therefore, if one area has a distinct sequence of layers, a trained geologist can tell you that region’s unique history. Let’s keep this “book” metaphor in mind.

When Wegener examined the layers of rock between two separate continents, he found something exciting. Places an ocean apart from each other, such as the Appalachians in the United States and the mountains extending through Greenland, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Norway had the same sequence of rocks. That is essentially finding the same book two continents apart.

What would a reasonable person conclude when finding the same book with two different covers? The same author wrote it. Much in the same spirit, Wegener concluded that these two mountain ranges in North America and Europe actually formed as one single chain hundreds of millions of years ago when these two continents were merged together. North America and Europe then drifted apart to the place we see them now on the world map.

Climatic Evidence

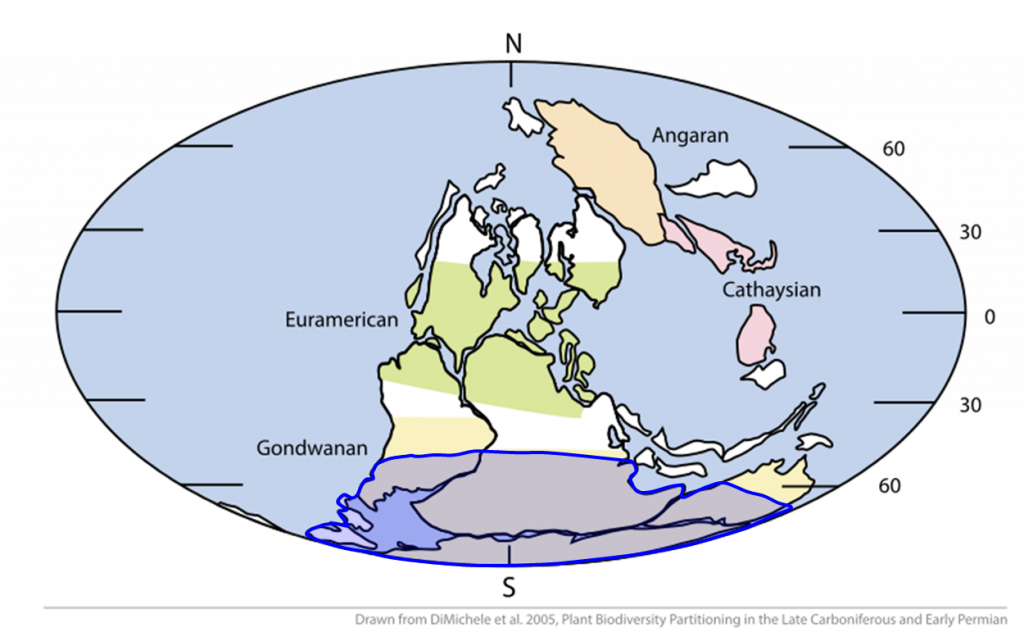

Let’s not forget that Wegener was a climatologist, and as he traveled the continents, he began to notice some strange patterns in the geologic record. Wegener found indications that places like southern Africa, India, Australia, and the Arabian subcontinent were once glaciated about 250 million years ago. He also discovered fossils of tropical plants in areas north of the Arctic Circle. In short, the rocks and fossils Wegener observed were telling him that places that we know today are cold were once hot, and places that are hot were once cold.

Wegener used these observations to further conclude that the continents must have moved. For example, Wegener knew that glaciers only formed near the poles in the modern day climate; therefore, he argued that to have glaciers, India, Australia, and Africa must have once been centered around the south pole. Similarly, today’s Arctic Circle must have once been around the tropics – approximately 23 °N and S in along Earth’s latitude to host tropical plant life [3].

Putting the Puzzle Together

After gathering a significant amount of evidence across the world, Alfred Wegener took the bold step of publishing his Continental Drift hypothesis in 1915 in a book entitled Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane or “The Origin of Continents and Oceans”. In this book, Wegener presents all of his evidence, and asserts that the continents must have once been together in a single landmass called “Ur kontinent” (supercontinent) or “Pangäa” (entire earth). Over large timescales of millions of years, this landmass broke apart, and the continents shifted into the configuration as we know them today.

In order to successfully argue for Continental Drift, Wegener also had the monumental task of dismantling the case for the Contracting Earth hypothesis and the popular idea that all ancient life moved across separate continents using narrow land bridges. In his book, Wegener makes the following appeal:

Backlash and Legacy

How Bad Was the Criticism Against Wegener?

“delirious ravings”

“moving crust disease and wandering pole plague.”

“Germanic pseudo-science”

“wrong for a stranger to the facts he handles to generalize from them”

“utter damned rot”

Alfred Wegener’s Final Expedition

Wegener’s scientific contributions were not only in the field of geosciences. As a climatologist, one of his passions was exploring the north of Greenland, which in the early 1900s had not been completely mapped. Wegener helped establish weather-monitoring stations on Greenland that took many readings of its brutal winter weather. This project became a lifelong love for Wegener despite the deadly risks each expedition posed. In 1928, even though Wegener was approaching his 50s, he departed again to explore northern Greenland. The weather was particularly bad (-76 degrees F) and one of the nearby camps was running low on food. He managed to travel through the terrible weather to resupply the camp on dog sleds, but the success was short-lived. Even with supplies, it was clear that the food would not last long enough for everyone. Therefore, he and another colleague volunteered to go back into the weather in the hopes of traveling to another camp. Wegener died on the journey from a heart attack, and his grave was marked with skis. His brother eventually discovered his body, but the family agreed that Wegener belonged in the field he so loved, and his final resting place has since remained Greenland [5,6].

***See 2.10 for Text and Media Attributions

a gravitational reaction of the Earth's crust to flex up or down when a large amount of material is deposited or eroded away.

A prevalent scientific idea up until the mid-20th century that states that Earth's landscapes tend to form due to the contraction of its crust.

A hypothesis that claims the Earth's landforms, specifically continents, move across the oceans over tens of millions of years.

a massive landmass composed of multiple continents formed by the collision of tectonic plates with smaller continents.