5 3.5 Silicate Minerals

The vast majority of the minerals that make up the rocks of Earth’s crust are silicate minerals. These include minerals such as quartz, feldspar, mica, amphibole, pyroxene, olivine, and a variety of clay minerals. The building block of all of these minerals is the silica tetrahedron, a combination of four oxygen atoms and one silicon atom. As we’ve seen, it’s called a tetrahedron because planes drawn through the oxygen atoms form a shape with 4 surfaces. Since the silicon ion has a charge of 4 and each of the four oxygen ions has a charge of −2, the silica tetrahedron has a net charge of −4.

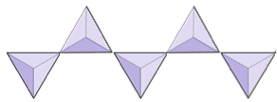

In silicate minerals, these tetrahedra are arranged and linked together in a variety of ways, from single units to complex frameworks (Table 3.6).

Silicate Structures

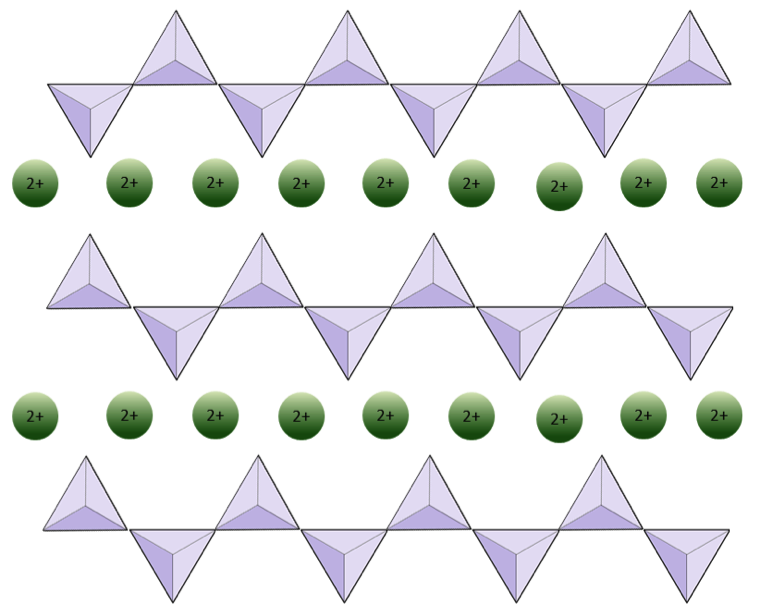

The simplest silicate structure, that of the mineral olivine, is composed of isolated tetrahedra bonded to iron and/or magnesium ions. In olivine, the −4 charge of each silica tetrahedron is balanced by two divalent (i.e., +2) iron or magnesium cations. Olivine can be either Mg2SiO4 or Fe2SiO4, or some combination of the two (Mg,Fe)2SiO4. The divalent cations of magnesium and iron are quite close in radius (0.73 versus 0.62 angstroms[1]). Because of this size similarity, and because they are both divalent cations (both can have a charge of +2), iron and magnesium can readily substitute for each other in olivine and in many other minerals.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Tetrahedron Configuration Picture | Tetrahedron Configuration Name | Example Minerals |

|---|---|---|

|

Isolated (nesosilicates) | Olivine, garnet, zircon, kyanite |

|

Pairs (sorosilicates) | Epidote, zoisite |

|

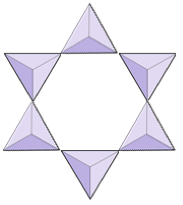

Rings (cyclosilicates) | Tourmaline |

|

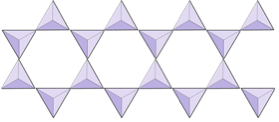

Single chains (inosilicates) | Pyroxenes, wollastonite |

|

Double chains (inosilicates) | Amphiboles |

|

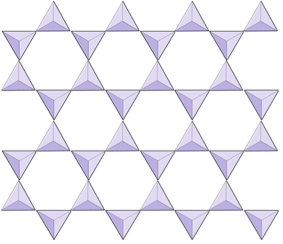

Sheets (phyllosilicates) | Micas, clay minerals, serpentine, chlorite |

| 3-dimensional structure | Framework (tectosilicates) | Feldspars, quartz, zeolite |

Isolated

In olivine, unlike most other silicate minerals, the silica tetrahedra are not bonded to each other. Instead they are bonded to the iron and/or magnesium ions, in the configuration shown on Figure 3.5.1.

As already noted, the 2 ions of iron and magnesium are similar in size (although not quite the same). This allows them to substitute for each other in some silicate minerals. In fact, the ions that are common in silicate minerals have a wide range of sizes, as depicted in Figure 2.4.2. All of the ions shown are cations, except for oxygen. Note that iron can exist as both a +2 ion (if it loses two electrons during ionization) or a +3 ion (if it loses three). Fe2+ is known as ferrous iron. Fe3+ is known as ferric iron. Ionic radii are critical to the composition of silicate minerals, so we’ll be referring to this diagram again.

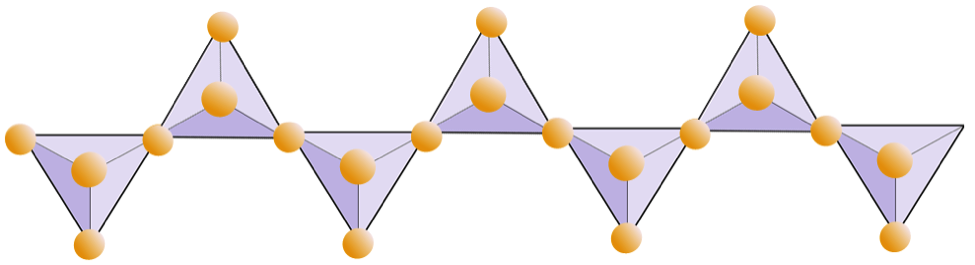

Single Chain

Exercise 2.4 Oxygen deprivation

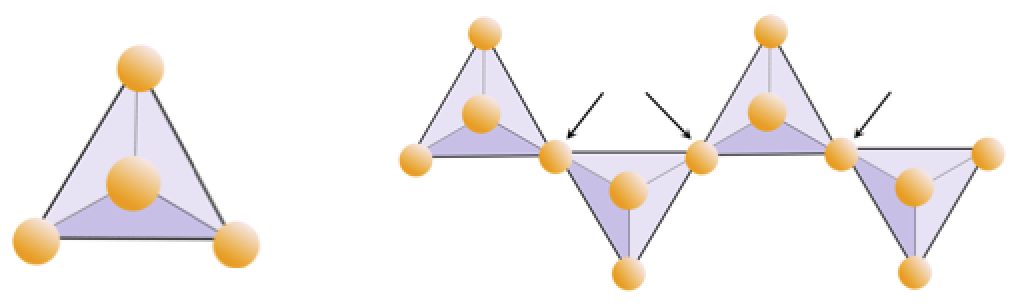

The diagram below represents a single chain in a silicate mineral. Count the number of tetrahedra versus the number of oxygen ions (yellow spheres). Each tetrahedron has one silicon ion so this should give you the ratio of Si to O in single-chain silicates (e.g., pyroxene).

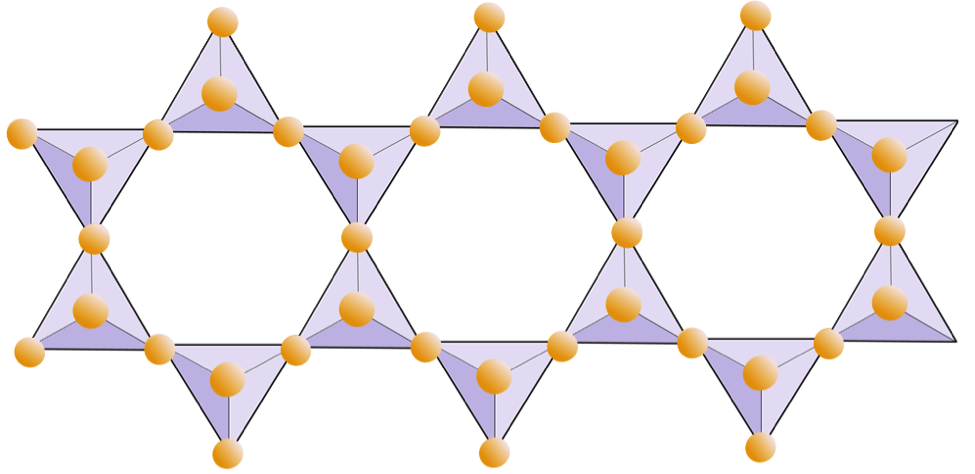

The diagram below represents a double chain in a silicate mineral. Again, count the number of tetrahedra versus the number of oxygen ions. This should give you the ratio of Si to O in double-chain silicates (e.g., amphibole).

Double Chain

In amphibole structures, the silica tetrahedra are linked in a double chain that has an oxygen-to-silicon ratio lower than that of pyroxene, and hence still fewer cations are necessary to balance the charge. Amphibole is even more permissive than pyroxene and its compositions can be very complex. Hornblende, for example, can include sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, aluminum, silicon, oxygen, fluorine, and the hydroxyl ion (OH−).

Sheet

In mica structures, the silica tetrahedra are arranged in continuous sheets, where each tetrahedron shares three oxygen anions with adjacent tetrahedra. There is even more sharing of oxygens between adjacent tetrahedra and hence fewer cations are needed to balance the charge of the silica-tetrahedra structure in sheet silicate minerals. Bonding between sheets is relatively weak, and this accounts for the well-developed one-directional cleavage in micas (Figure 3.5.5). Biotite mica can have iron and/or magnesium in it and that makes it a ferromagnesian silicate mineral (like olivine, pyroxene, and amphibole). Chlorite is another similar mineral that commonly includes magnesium. In muscovite mica, the only cations present are aluminum and potassium; hence it is a non-ferromagnesian silicate mineral.

Apart from muscovite, biotite, and chlorite, there are many other sheet silicates (a.k.a. phyllosilicates), many of which exist as clay-sized fragments (i.e., less than 0.004 millimeters). These include the clay minerals kaolinite, illite, and smectite, and although they are difficult to study because of their very small size, they are extremely important components of rocks and especially of soils.

All of the sheet silicate minerals also have water molecules within their structure.

Framework

Silica tetrahedra are bonded in three-dimensional frameworks in both the feldspars and quartz. These are non-ferromagnesian minerals—they don’t contain any iron or magnesium. In addition to silica tetrahedra, feldspars include the cations aluminum, potassium, sodium, and calcium in various combinations. Quartz contains only silica tetrahedra.

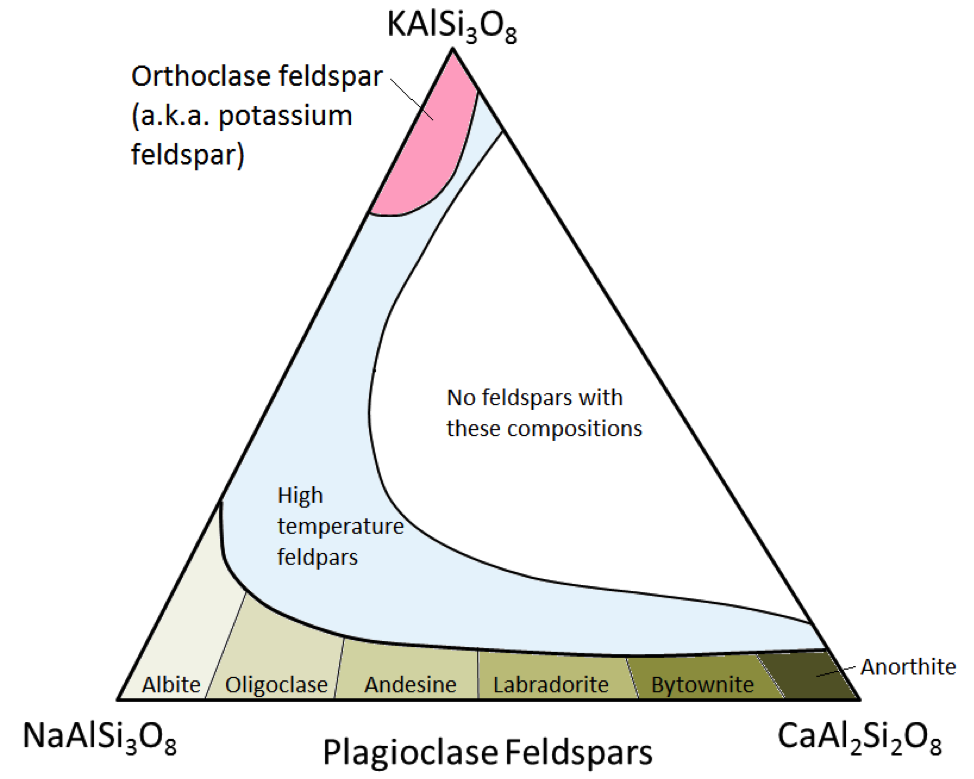

The three main feldspar minerals are potassium feldspar, (a.k.a. K-feldspar or K-spar) and two types of plagioclase feldspar: albite (sodium only) and anorthite (calcium only). As is the case for iron and magnesium in olivine, there is a continuous range of compositions (solid solution series) between albite and anorthite in plagioclase. Because the calcium and sodium ions are almost identical in size (1.00 Å versus 0.99 Å) any intermediate compositions between CaAl2Si3O8 and NaAlSi3O8 can exist (Figure 3.5.6). This is a little bit surprising because, although they are very similar in size, calcium and sodium ions don’t have the same charge (Ca2+ versus Na+ ). This problem is accounted for by the corresponding substitution of Al+3 for Si+4 . Therefore, albite is NaAlSi3O8 (1 Al and 3 Si) while anorthite is CaAl2Si2O8 (2 Al and 2 Si), and plagioclase feldspars of intermediate composition have intermediate proportions of Al and Si. This is called a “coupled-substitution.”

The intermediate-composition plagioclase feldspars are oligoclase (10% to 30% Ca), andesine (30% to 50% Ca), labradorite (50% to 70% Ca), and bytownite (70% to 90% Ca). K-feldspar (KAlSi3O8) has a slightly different structure than that of plagioclase, owing to the larger size of the potassium ion (1.37 Å) and because of this large size, potassium and sodium do not readily substitute for each other, except at high temperatures. These high-temperature feldspars are likely to be found only in volcanic rocks because intrusive igneous rocks cool slowly enough to low temperatures for the feldspars to change into one of the lower-temperature forms.

In quartz (SiO2), the silica tetrahedra are bonded in a “perfect” three-dimensional framework. Each tetrahedron is bonded to four other tetrahedra (with an oxygen shared at every corner of each tetrahedron), and as a result, the ratio of silicon to oxygen is 1:2. Since the one silicon cation has a +4 charge and the two oxygen anions each have a −2 charge, the charge is balanced. There is no need for aluminum or any of the other cations such as sodium or potassium. The hardness and lack of cleavage in quartz result from the strong covalent/ionic bonds characteristic of the silica tetrahedron.

***See 3.10 for Text and Media Attributions

- An angstrom is the unit commonly used for the expression of atomic-scale dimensions. One angstrom is 10−10 meters or 0.0000000001 meters. The symbol for an angstrom is Å. ↵

A central silicon atom surrounded by four oxygen atoms. The basic building block of silicate minerals.

(Mg,Fe)SiO4

A class of silicate mineral that forms at high temperatures and can have a magnesium (Mg) or iron (Fe) rich composition.

(Mg,Ca,Fe)SiO3

A class of dark-colored silicate minerals that form under high temperatures and/or pressures. These form in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

a class of silicate minerals that are usually dark and form long crystals (as prisms or needles). Amphiboles are often magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe) rich in composition.

A group of silicate minerals called the "sheet" silicates. Mica minerals have their atomic structure arranged to easily pull apart as sheets in one direction.

A type of mica that is black or dark-colored and is typically found in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

containing iron and magnesium as major components.

a dark green mineral consisting of a basic hydrated aluminosilicate of magnesium and iron.

A common mineral in the mica group that is light grayish-brown. It is flaky and peels apart in sheets.

Al2Si2O5(OH)4

A type of clay silicate mineral that is white or very light-colored. It has historically been used for making porcelain.

A group of silicate minerals which represents the most abundant mineral class of the continental crust.

A very common rock-forming silicate mineral with formula SiO2.