6.1 Brittle Deformation

Deformation, Stress, and Strain

As we learned from our lesson on plate tectonics, the Earth’s crust is constantly in motion. This motion can lead to the collision of mountains, the rifting of valleys, and the shearing of the surface. These processes cause deformation on our surface.

The forces that act over an area of rock, such as pressure from the layers of rocks above them, are called stress. Stress is any force applied over an area.

There are generally two types of stress. The first is confining stress, which is stress that is perfectly applied to all sides of the rock.

Imagine that you have a ball of putty/Play-Doh.

The second type of stress is called differential stress, which is stress that is applied unevenly to one or different sides of the rock.

After enough stress is applied to a rock, deformation occurs, which is called strain – the resulting displacement or movement of material from stress.

There are two main types of deformation that we can observe on Earth’s surface: brittle deformation and plastic deformation. Although they are both consequences of similar processes, they occur at different temperatures and pressures, and as a result, these two types of deformation result in very different-looking features!

Please watch the video below for a summary on all these features: folds and faults!

Brittle Deformation

When enough stress is applied to a rock or layer that is not subjected to significantly high temperatures and pressures, the rock can fracture along a point of weakness. This fracture is called brittle deformation. This type of deformation occurs commonly in the upper crust in the form of fractures, joints, and faulting. Faults involve the physical dislocation of rock layers along a shear plane or plane of weakness. Below are the classifications of faults:

Dip-Slip Faults

These faults move vertically. Two types of dip-slip faults include:

Normal Faults: These faults occur when blocks of rock are pulled apart.

Reverse or Thrust Faults: These occur when blocks of rock are pushed together.

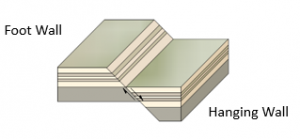

Other terminology related to dip-slip faults is the footwall, which is the underlying block on the fault. The hanging wall is the overlying block on the fault. You can also tell the footwall apart from the hanging wall by the “shoe”-like shape it tends to have.

Strike-Slip Faults

These faults move horizontally. Two types of strike-slip faults include:

Left-lateral Faults : If you stand on the fault line of this fault, the left block would move toward you and the right would move away.

Right-Lateral Faults (example also shown in the gif above): If you stand on the fault line of this fault, the right block would move toward you, and the left would move away.