1.1 Earth’s Interior

After reading the chapter on Plate Tectonics and the Earth’s interior, you are going to have a LOT information to digest. What’s the difference between the inner and outer core? What is a divergent boundary? Why is Hawaii so volcanically active if it’s nowhere near a plate boundary? What is the Ring of Fire anyway!? These lab exercises are here to help, starting with all the new terminology you’ve learned in the assigned reading. This section is your go-to stop to focus on the jargon words that geologists love to use. By the end of this section, you should have a stronger understanding of what these terms mean.

Let’s Review the Terms!

In the below exercise, don’t worry about what the words mean. You just need to identify them in the word search block!

Earth’s Interior

We previously learned about the layers of the Earth’s interior, from surface to center. Can you identify them on a diagram?

Now it’s time to get a better idea of what some of the terms actually mean, and how they differ from one another. Let’s take a close look at our crust. We know the MOST about our crust out of all the layers of the Earth. Why is that? Well, it’s the one layer that we live on and can most easily study. The Earth’s crust does not extend very far into the Earth, only a variable amount of about 5-70 km – so we a literally scratching the surface when it comes to our knowledge. However, here are some things that we know:

- Layers like the crust, mantle, and core are chemical layers in the Earth’s interior. This means these are identified as different based on how the amounts of important elements like Mg, Fe, and Si change in each layer!

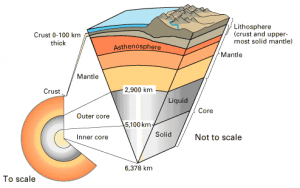

- Another way of identifying the top layer and other interior layers of the planet is by their physical properties. Some physical properties include density, resistance to breaking, rigidity, etc. Whereas the topmost chemical layer of our Earth is the crust, the topmost physical layer of our Earth is the lithosphere. This is just a different way of classifying the same material–the lithosphere overlaps with the crust and goes down to about 100 km deep!

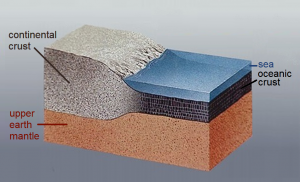

Figure 1.1.1 Cutaway schematic of the Earth demonstrating the lithosphere layer (making up the crust and rigid part of the upper mantle) and asthenosphere layer. Image by USGS, Public Domain. - There are two types of crust on our planet – oceanic and continental crust. We noticed long ago that the crust is a lot thinner beneath oceans, whereas it is a lot thicker on continental landmasses. There is a good reason for this; the continental crust is very old and almost never gets destroyed. It is not very dense and therefore up to 70 km thick. By contrast, the oldest oceanic crust is about 250 million years old. Oceanic crust is about 5 km thin, and much denser.

Figure 1.1.2 The continental crust is much thicker than the oceanic crust, which means that continental lithosphere is also thicker than oceanic lithosphere. Image by USGS, Public Domain CCO - The reason that continental crust is never destroyed is that it is not very dense; it does not sink into the mantle. The minerals and rocks that compose this crust are called FELSIC; they are made of lighter FELdspar and SIliCA.

- The reason that oceanic crust is thin and young is that it easily sinks into the mantle when it gets colder and older due to its high density. The minerals and rocks that compose this type of crust are called MAFIC; they are made of the elements MAGnesigum and FerrIC iron.

Figure 1.1.3 Mafic rocks containing iron and magnesium are typically darker and denser, whereas felsic rocks are less dense and lighter in color. Both images Public Domain, adapted by Charlene Estrada (CC0).

Each one of the layers of Earth’s interior has a unique property, as you’ve learned from the reading assignment. What are they?