Culture Shock

As part of the acculturation process individuals may experience culture shock, which occurs when individuals move to a cultural environment which is different from their own. It can also describe the disorientation we feel when exposed to an unfamiliar way of life due to immigration to a new country, a visit to a new country, move between social environments (e.g., moving away for college), or transitioning to another type of life (e.g, dating after divorce). Common issues associated culture shock include: loss of status (e.g., provider to unemployed), unfamiliar social systems and social norms (e.g., agencies rather than extended kin networks), distance from family and friends, information overload, language barriers, generation gap, and possible technology gap. There is no way to prevent culture shock because everyone experiences and reacts to the contrasts between cultures differently.

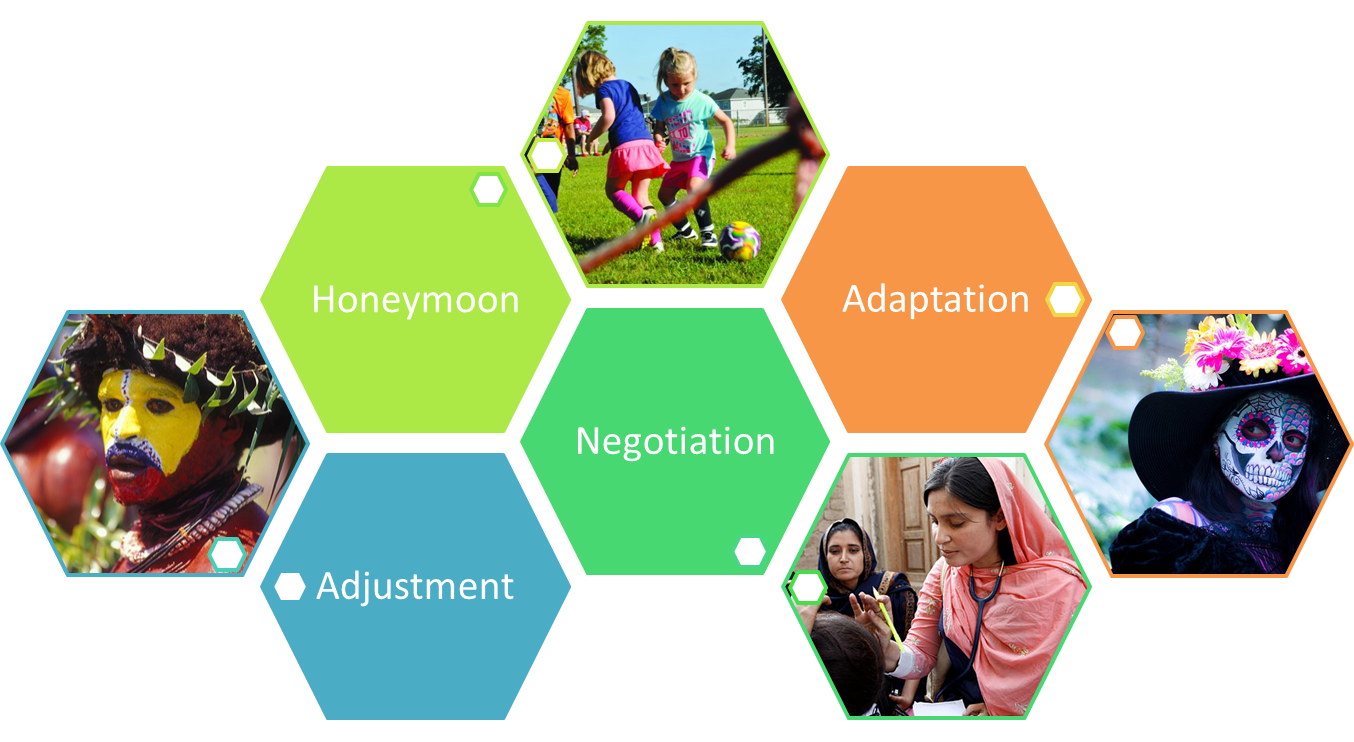

Culture shock consists of at least one of four distinct phases:

- Honeymoon

- Negotiation

- Adjustment

- Adaptation

Honeymoon

During this period, the differences between the old and new culture are seen in a romantic light. For example, after moving to a new country, an individual might love the new food, the pace of life, and the locals’ habits. During the first few weeks, most people are fascinated by the new culture. They associate with individuals who speak their language and who are polite to the foreigners. Like most honeymoon periods, this stage eventually ends.

Negotiation

After some time (usually around three months depending on the individual), differences between the old and new culture become more apparent and may create anxiety or distress. Excitement may eventually give way to irritation, frustration and anger as one continues to experience unpleasant events that are strange and offensive to one’s own cultural attitude. Language barriers, stark differences in public hygiene, traffic safety, food accessibility and quality may heighten the feelings of disconnection from the surroundings.

Living in a different environment can have a negative, although usually short term, effect on our health. While negotiating culture shock we may have insomnia because of circadian rhythm disruption, problems with digestion because of gut flora due to different bacteria levels and concentrations in food and water, and difficulty in accessing healthcare or treatment (e.g., medicines with different names or active ingredients).

During the negotiation phase, people adjusting to a new culture often feel lonely and homesick because they are not yet used to the new environment and encounter unfamiliar people, customs and norms every day. The language barrier may become a major obstacle in creating new relationships. Some individuals find that they must pay special attention to culturally specific body language (e.g., arms crossed, smiling), conversation tone, and linguistic nuances and customs (e.g, handshake, turn taking, ending a conversation). International students often feel anxious and feel more pressure while adjusting to new cultures because there is special emphasis on their reading and writing skills.

Adjustment

As more time passes (usually 6 to 12 months) individuals generally grow accustomed to the new culture and develop routines. The host country no longer feels new and life becomes “normal”. Problem-solving skills for dealing with the culture have developed and most individuals accept the new culture with a positive attitude. The culture begins to make sense, and negative reactions and responses to the culture have decreased.

Adaption

In the adaptation stage individuals are able to participate fully and comfortably in the host culture but this does not mean total conversion or assimilation. People often keep many traits from their native culture, such as accents, language and values. This stage is often referred to as the bicultural stage.