Intelligence

Psychologists have long debated how to best conceptualize and measure intelligence (Sternberg, 2003). These questions include how many types of intelligence there are, the role of nature versus nurture in intelligence, how intelligence is represented in the brain, and the meaning of group differences in intelligence. The concept of intelligence relates to abstract thinking and that includes our abilities to acquire knowledge, to reason abstractly, to adapt to novel situations, and to benefit from instruction and experience (Gottfredson, 1997; Sternberg, 2003). The brain processes underlying intelligence are not completely understood, but current research has focused on four potential factors:

- Brain size

- Sensory ability

- Speed and efficiency of neural transmission

- Working memory capacity

There is some truth to the idea that smarter people have bigger brains. Studies that have measured brain volume using neuroimaging techniques find that larger brain size is correlated with intelligence (McDaniel, 2005), and intelligence has also been found to be correlated with the number of neurons in the brain and with the thickness of the cortex (Haier, 2004; Shaw et al., 2006). It is important to remember that these correlational findings do not mean that having more brain volume causes higher intelligence. It is possible that growing up in a stimulating environment that rewards thinking and learning may lead to greater brain growth (Garlick, 2003), and it is also possible that a third variable, such as better nutrition, causes both brain volume and intelligence.

There is some evidence that brains of more intelligent people operate more efficiently than the brains of people with less intelligence. Haier, Siegel, Tang, and Abel (1992) analyzed data showing that people who were more intelligent showed less brain activity than those with lower intelligence when they worked on a task. Researchers suggested that more intelligent brains need to use less capacity. Brains of more intelligent people also seem to operate faster than the brains of those who are less intelligent. Research has found that the speed with which people can perform simple tasks, like determining which of two lines is longer or quickly pressing one of eight buttons that is lighted, was predictive of intelligence (Deary, Der, & Ford, 2001). Intelligence scores also correlate at about r = .5 with measures of working memory (Ackerman, Beier, & Boyle, 2005), and working memory is now used as a measure of intelligence on many tests.

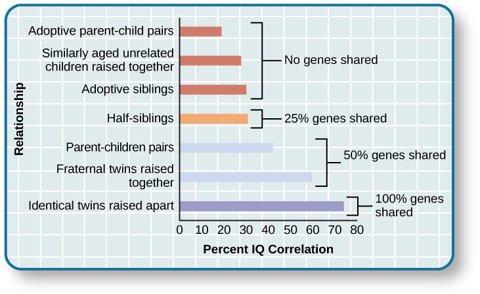

Research using twin and adoption studies found that intelligence has both genetic and environmental causes (Neisser et al., 1996; Plomin, DeFries, Craig, & McGuffin, 2003). It appears that 40% – 80% of the variability (difference) in intelligence is due to genetics (Plomin & Spinath, 2004). The intelligence of identical twins correlates very highly at r = .86, which is much higher than the scores of fraternal twins who are less genetically similar (r = .60). Correlations between the intelligence of parents and their biological children (r = .42) is significantly higher than the correlation between parents and adopted children (r = .19). The intelligence of very young children (less than 3 years old) does not predict adult intelligence but by age 7 intelligence scores (as measured by a standard test) remain very stable in adulthood (Deary, Whiteman, Starr, Whalley, & Fox, 2004).

There is also strong evidence for the role of nurture, which indicates that individuals are not born with fixed, unchangeable levels of intelligence. Twins raised together in the same home have more similar intelligence scores than do twins who are raised in different homes, and fraternal twins have more similar intelligence scores than do non-twin siblings, which is likely due to the fact that they are treated more similarly than are siblings. Additionally, intelligence becomes more stable as we get older which provides evidence that early environmental experiences matter more than later ones.

Environmental factors also explain a greater proportion of the variance in intelligence and social and economic deprivation can adversely affect intelligence. Children from households in poverty have lower intelligence scores than children from households with more resources even when other factors such as education, race, and parenting are controlled (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997). Poverty may contribute to diets that undernourished the brain or lack appropriate vitamins. Poor children are more likely to be exposed to toxins such as lead in drinking water, dust, or paint chips (Bellinger & Needleman, 2003). Both of these factors can slow brain development and reduce intelligence.

Intelligence is improved by education and the number of years a person has spent in school correlates about r = .6 with intelligence (Ceci, 1991). There is a word of caution when interpreting this result. The correlation may be due to the fact that people with higher intelligence scores enjoy taking classes more than people with low intelligence scores, and may be more likely to stay in school. Children’s intelligence scores tend to drop significantly during summer vacations (Huttenlocher, Levine, & Vevea, 1998), a finding that suggests a causal effect of intelligence and education. A longer school year, as is used in Europe and East Asia, may be beneficial for maintaining intelligence scores for school-aged children.

One or Many

As learned earlier, intelligence is associated with the brain, includes abstract thinking, adapting to new situations, ability to benefit from instruction and experience (Gottfredson, 1997; Sternberg, 2003) and is largely determined by genetics. Psychologist Charles Spearman (1863–1945) hypothesized that there must be a single underlying construct that links these concepts, abilities and skills together. He called this construct the general intelligence factor (g) and there is strong empirical support for a single dimension to intelligence. Others psychologists believe that instead of a single factor, intelligence is a collection of distinct abilities. Raymond Cattell proposed a theory of intelligence that divided general intelligence into two components: crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence (Cattell, 1963).

Crystallized intelligence is characterized as acquired knowledge and the ability to retrieve it. When you learn, remember, and recall information, you are using crystallized intelligence. You use crystallized intelligence all the time in your coursework by demonstrating that you have mastered the information covered in the course.

Fluid intelligence encompasses the ability to see complex relationships and solve problems. Navigating your way home after being detoured onto an unfamiliar route because of road construction would draw upon your fluid intelligence. Fluid intelligence helps you tackle complex, abstract challenges in your daily life, whereas crystallized intelligence helps you overcome concrete, straightforward problems (Cattell, 1963).

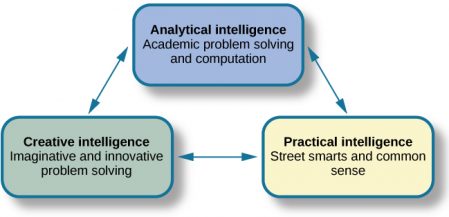

Robert Sternberg developed another theory of intelligence, which he titled the triarchic theory of intelligence because he proposed that intelligence is comprised of three parts (Sternberg, 1988): creative, analytical, and practical intelligence. (CAP).

- Creative intelligence is marked by inventing or imagining a solution to a problem or situation. Creativity in this realm can include finding a novel solution to an unexpected problem or producing a beautiful work of art or a well-developed short story.

- Analytical intelligence is closely aligned with academic problem solving and computations. Sternberg says that analytical intelligence is demonstrated by an ability to analyze, evaluate, judge, compare, and contrast. For example, in a science course such as anatomy, you must study the processes by which the body uses various minerals in different human systems. In developing an understanding of this topic, you are using analytical intelligence.

- Practical intelligence is sometimes compared to “street smarts.” Being practical means you find solutions that work in your everyday life by applying knowledge based on your experiences.

Multiple Intelligences Theory was developed by Howard Gardner and asserts that everybody possesses at least eight distinct types of intelligence. Among these eight intelligences, a person typically excels in some and falters in others (Gardner, 1983). Gardner’s theory is relatively new and needs additional research to establish empirical support. At the same time, his ideas challenge the traditional idea of intelligence to include a wider variety of abilities but creating a test to measure all of Gardner’s intelligences has been extremely difficult (Furnham, 2009; Gardner & Moran, 2006; Klein, 1997).

Intelligence and Culture

Intelligence can also have different meanings and values in different cultures. If you live on a small island, where most people get their food by fishing from boats, it would be important to know how to fish and how to repair a boat. If you were an exceptional angler, your peers would probably consider you intelligent. If you were also skilled at repairing boats, your intelligence might be known across the whole island. In Irish families, hospitality and telling an entertaining story are marks of the culture. If you are a skilled storyteller, other members of Irish culture are likely to consider you intelligent. Some cultures place a high value on working together as a collective. In these cultures, the importance of the group supersedes the importance of individual achievement. When you visit such a culture, how well you relate to the values of that culture exemplifies your cultural intelligence, sometimes referred to as cultural competence.

Intelligence Tests

Reliable intelligence testing began in the early 1900s with researchers named Alfred Binet and Henri Simon. They were instructed by the French government to develop an intelligence test to use on children in order to determine which ones might have difficulty in school. The test included many verbally based tasks. American researchers soon realized the value of such testing and Louis (Lewis) Terman, a Stanford professor, modified Binet’s work by standardizing the administration of the test, which was standardized by testing thousands of different-aged children in the United States to establish an average score for each age group. The Stanford-Binet, is a measure of general intelligence made up of a wide variety of tasks including vocabulary, memory for pictures, and naming of familiar objects and is primarily used with children.

Later, David Wechsler created an adult intelligence test named the Wechsler Adult intelligence Scale (WAIS), which is the most widely used intelligence test for adults (Watkins, Campbell, Nieberding, & Hallmark, 1995). The current version of the WAIS, consists of 15 different tasks including working memory, arithmetic ability, spatial ability, and general knowledge about the world. These 15 tasks measure a dimension of intelligence and provide psychologists with four domains scores: verbal, perceptual, working memory, and processing speed. The WAIS is highly correlated with the Stanford-Binet, as well as with criteria of academic and life success, including college grades, measures of work performance, and occupational level. It also shows significant correlations with measures of everyday functioning among individuals with intellectual disabilities.