3.1 What Is A Mineral?

Charlene Estrada

Minerals

You have probably heard the term “mineral” commonly used before to describe ingredients in food, beverages, or beauty products. In geosciences, a mineral is something different. Geologists define a mineral as an inorganic crystalline solid substance with a definite chemical composition that forms through natural processes.

This sounds like a pretty narrow definition, but this precise wording helps scientists decide when materials are – or are not – minerals. Let’s inspect each of the requirements that a material must meet in order to be considered a mineral!

Minerals are crystalline solids

For a substance to be considered a mineral, it first must be solid. For example, we do not consider liquid water a mineral; but frozen water, or ice, is a mineral. Why do we make this distinction? Aren’t ice and water made of the same thing, H2O?

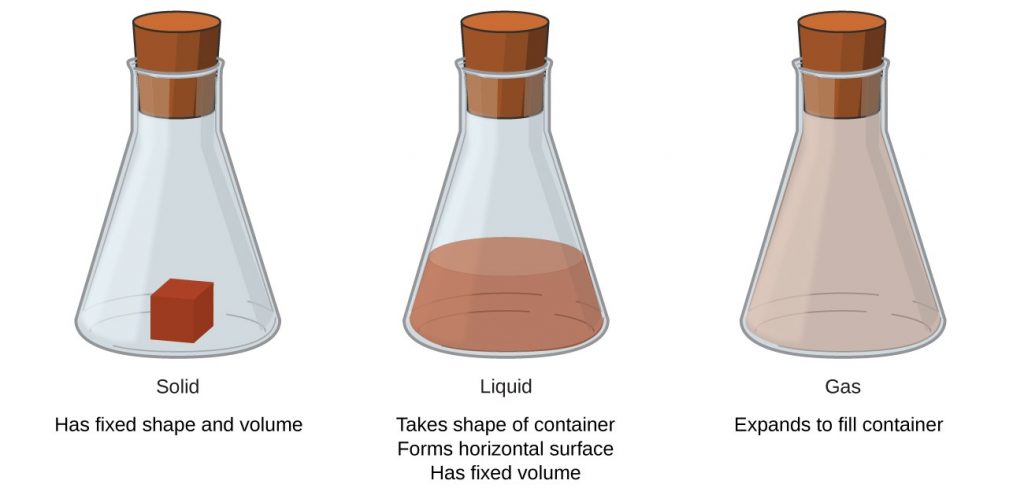

A key identifier in mineralogy is the crystal structure of a mineral. Let’s do a quick review of some chemistry! All matter or “stuff” in our universe can take on just one of four forms: solid, liquid, gas, or plasma. When matter settles into one of these forms, the atoms that compose it will act differently. There is a lot of space between atoms in a gaseous state. The atoms or molecules occupy all the space available. In the liquid state, the atoms are closer together, they move at a slower pace and have less range of motion. However, liquids will take the shape of the container and flow. In a solid state, the densely packed atoms are nearly “frozen” in place. Thus, solids have a defined volume and shape. They also have a predictable structure, as we discuss below. Remember, in geology, a mineral must be a solid.

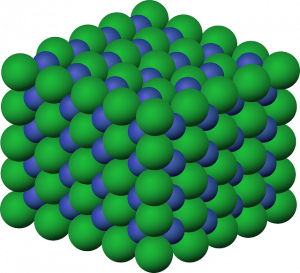

A crystal is a solid in which the atoms are arranged into a repeating pattern that can be predicted, that is a crystal structure. This definition means that if you had two samples of ice, one from Antarctica, and one from your freezer, they should have the exact same atomic arrangement! Knowing this property allows scientists to identify unknown crystals with instruments called X-ray Diffractometers that can view their atomic structure.

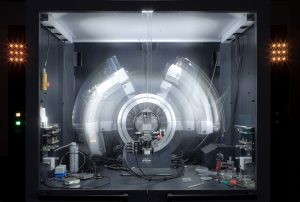

How It Works: X-ray Diffraction How can scientists map the location of atoms in a crystal structure? Believe it or not, this has been a widely available technique long before the development of powerful (and expensive) microscopes that can view objects down at the atomic level. In the early 1900s, scientists discovered that they can determine the distance of bonds between atoms in a crystal by passing X-rays through it. This is done by aiming the X-rays at many different angles throughout the crystals and observing how the crystal structure interferes with – or “diffracts” – the beams.

In the world of mineralogy, predictability is key, which is why solid crystals like ice are called “minerals”. There are still lots of solid materials out there that do not meet the definition of crystal. A good example is glass. Most glass is made of silica, which has the formula SiO2. However, most glass is also an amorphous solid, meaning that it has no predictably ordered arrangement of the silicon and oxygen atoms.

Minerals have definite chemical composition

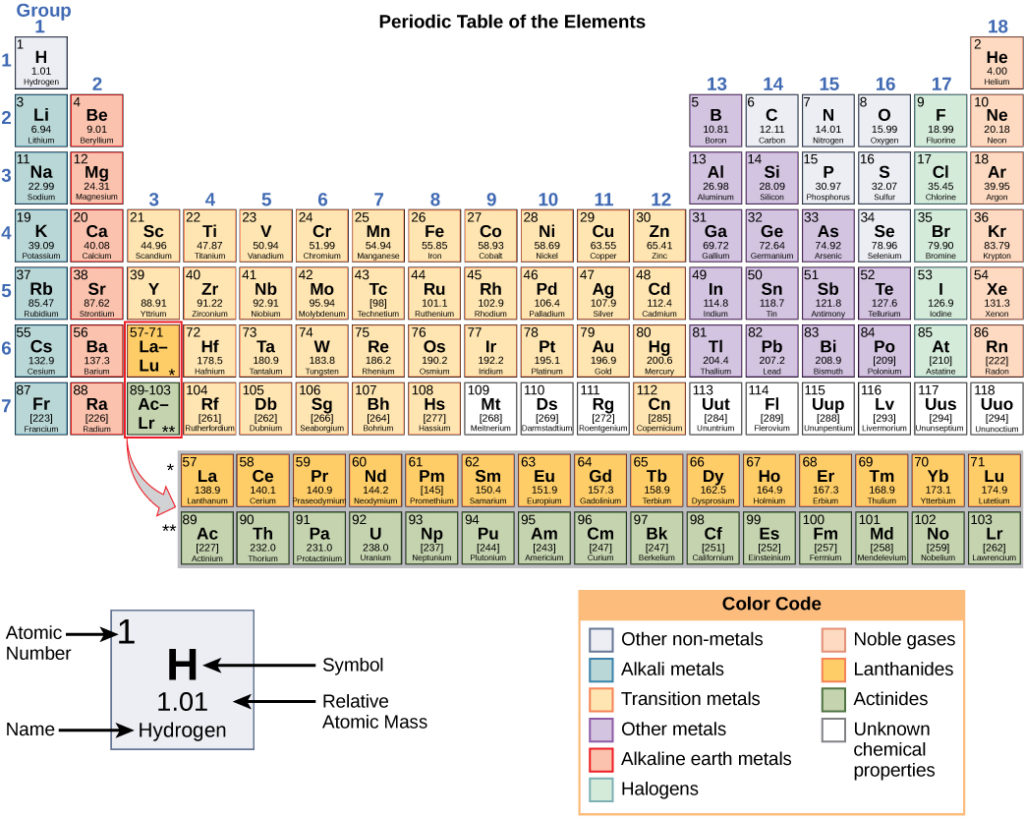

All minerals have a definite chemical composition. To understand chemical composition, we first need to understand elements and bonds. A chemical element is a pure substance, all the atoms are the same. The atoms that make up chemical elements are represented in the Periodic Table of Elements (Fig. 3.1.5). One atom can make up a chemical element and bond with another chemical element. When two atoms of different elements combine, or bond, they form a compound. A molecule is a version of a compound that could have the same or different elements.

Video 3.1.2. In this chemistry video, you can review the differences between element, mixture, and compound using iron and sulfur as an example (5:05).

A “definite” chemical composition means that every time we encounter the substance, we will know what type of elements compose it. For example, if you were lucky enough to find a nugget of gold, you would know that it contains only gold (Au) atoms. The mineral diamond is made of only carbon (C) atoms, in a specific arrangement. Most minerals comprise compounds rather than single elements. We still assign each mineral a chemical formula so that we may know what is in it. Halite (rock salt) has the formula NaCl (sodium chloride). Quartz is made of silica, which is represented by the formula SiO2. Sometimes the elements within a chemical formula give a mineral unique properties such as toxicity or radioactivity. For instance, the mineral uraninite is radioactive because it contains uranium in its chemical formula, UO2.

A good way to tell that a substance is NOT a mineral is the absence of a chemical formula. This is often true for rocks; most rocks contain multiple minerals and thus their composition ranges. While we know what minerals need to be present in a rock to be called a basalt, sandstone, or schist, the specific formula for each rock will vary.

Minerals are inorganic substances

Organic substances are compounds made of carbon and hydrogen bonds that include proteins, carbohydrates, and oils. Inorganic substances have a structure that is not characteristic of living tissues. Let’s consider coal as an example. Coal is a sedimentary rock that generally consists of the element carbon (C). Does that make coal a mineral?

No. Coal is not a mineral because it forms when plants and animals decay and their organic matter is compacted together over millions of years. Because coal consists of organic substances, it cannot be a mineral, even if it is also solid. But what about calcite? Some organisms such corals, coccolithophores, bivalves, and brachiopods will build their shells out of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is the formula for the mineral calcite. In fact, the ancient trilobites precipitates eyes made out of this mineral. Does that mean that calcite, like coal, is not a mineral?

Not exactly! Think about how we define organic substances above–they are things that are built with carbon and hydrogen bonds to develop living tissues. The formula for calcite is CaCO3. Furthermore, not all calcite crystals make up living materials – in fact, most calcite is NOT precipitated by life! A mineral CAN be produced by natural processes such as a biological precipitation; however, we cannot have minerals made of proteins or sugars.

Minerals are formed by natural processes

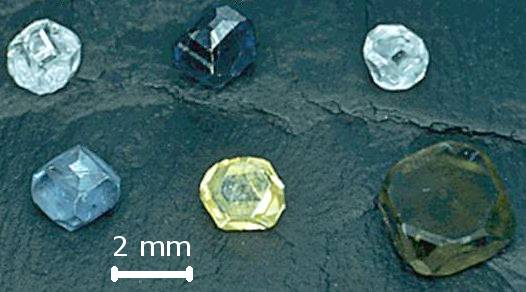

Minerals are only made by natural processes that occur in our universe. This criterion has been made more important because of the recent innovation of synthetic minerals. In the last several decades, scientists have made breakthroughs in mimicking the extraordinary pressures and temperatures required in nature to produce expensive gemstones such as diamonds. It is now possible to take any source of carbon, such as peanut butter or even a favorite pet’s ashes, and subject them to mantle conditions in a laboratory setting to create a brand new diamond.

As exciting as this process is, these synthetic gemstones are not “real” minerals. Minerals are only formed naturally by geologic processes or are naturally precipitated by organisms. Be sure that if you consider purchasing a laboratory-made gemstone you know that most geoscientists (and gemologists) do not think of them as real minerals!

Key Takeaways

A mineral is:

✔︎solid

✔︎with a crystal or atomic structure

✔︎definite chemical composition that you can write as a chemical formula

✔︎formed by natural processes, and

✔︎ inorganic.

a solid, inorganic, and crystalline substance that has a predictable chemical composition and form by natural processes.

A substance with its atoms arranged in a solid, repetitive structure.

The study, characterization, and identification of minerals.

Anything in the Universe that takes up space and has a mass.

The smallest unit of matter that can still form a chemical element.

A solid in which the atoms are arranged into a regular, repeating pattern.

An instrument that can determine the spacing of atoms in a crystal structure using X-ray radiation in order to identify a particular mineral.

a compound composed of silicon and oxygen in the formula SiO2.

A pure substance that is not composed of any other ingredients found in the Periodic Table of Elements. One atom can be composed of only one element and form bonds with other elements.

A table that displays all known chemical elements in order of atomic number, chemical property, and electron configuration.

A substance composed of two or more atoms. A compound is made of different elements.

Two or more atoms that are connected by a bond. These atoms can be the same element or different elements.

a metallic, brassy-yellow mineral made only of the element gold (Au). It is a precious metal in the world economy.

An extremely hard mineral composed only of carbon (C). It is a precious mineral that can take on a glassy to brilliant luster and it is sometimes a conflict resource.

NaCl

A salty, halide mineral that is often colorless or white. Halite is commonly known as rock salt and used globally as a condiment. It tends to form as cubic-shaped grains or crystals.

A very common rock-forming silicate mineral with formula SiO2.

A chemical molecule or compound that contains carbon and hydrogen bonds in its structure that is often used as nutrients or tissues for living organisms.

A complex molecule that is a building block in all known life that carries out essential tasks in metabolism.

A common type of organic molecule found in all known life that is usually used to store energy.

An organic sedimentary rock formed by the compaction of plant and animal organic matter over millions of years.

rocks that cement together from weathering products, either from sediments or chemical ions in water.

CaCO3

A carbonate mineral that strongly reacts with dilute acid. Calcite composes the sedimentary rock limestone and composes the skeletons of some ocean life.

A round, oceanic microorganism with a calcium carbonate exoskeleton consisting of multiple plates. Sometimes also called a coccolith.

A shelled water-dwelling organism from the lophotrochozoan group of animals. Although they appear like clams, there is asymmetry between the top and bottom shells.

An ancient, sea-dwelling creature from the arthropod family with a body separated into three lobes. Trilobites went extinct about 252 million years ago during the Permian Mass Extinction.