3.6 Sedimentary Rocks

Charlene Estrada

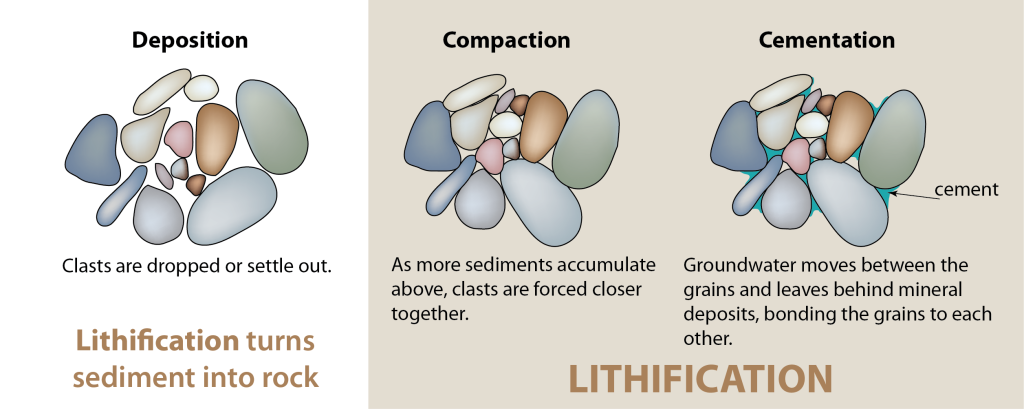

When a geologist encounters a sedimentary outcrop, they can reconstruct ancient landscapes – rapidly flowing mountain streams, frightening avalanches, or vast deserts – from these rocks. As the name suggests, Sedimentary Rocks are composed of sediments that have been cemented and compacted together, or lithified, over long periods of time.

Sediments may include:

- Fragments of other rocks that often have been worn down into small pieces, such as sand, silt, or clay.

- Organic materials, or the remains of once-living organisms.

- Chemical precipitates, which are materials that get left behind after the water evaporates from a solution.

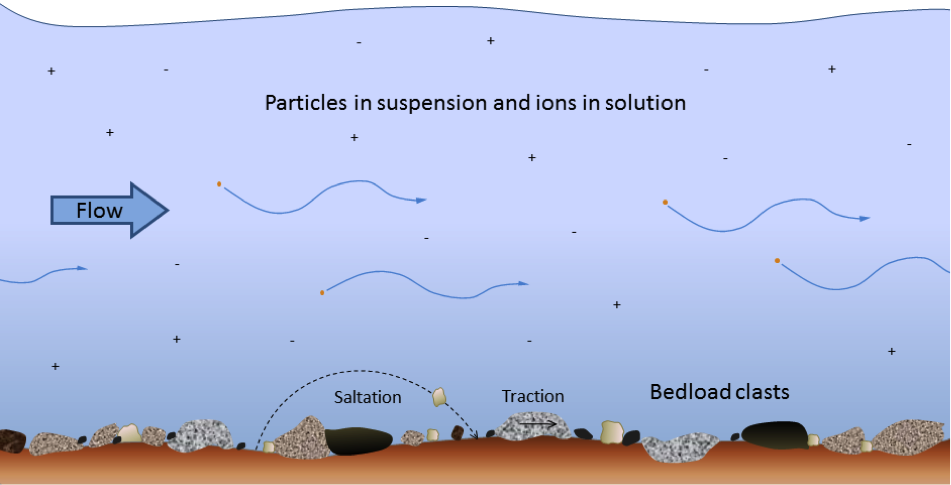

Both physical and chemical weathering processes that take place at the Earth’s surface are responsible for accumulating this source of sediment from preexisting igneous rocks, metamorphic rocks, and even other sedimentary rocks. Physical weathering breaks the rocks apart, while chemical weathering dissolves the less stable minerals. These original elements of the minerals end up in solution, and new minerals may form. Water, wind, ice, or gravity remove and transport sediments in a process called erosion.

We can classify sedimentary rocks in two broad categories: clastic and chemical. Clastic sedimentary rocks are made from the fragments of eroded bedrock and sediment, which is usually derived from physical weathering. We classify clastic rocks by their grain size, shape, and sorting. Chemical Sedimentary rocks are precipitated from water that contains a very high concentration of dissolved elements, or ions. We usually classify these chemical rocks based on the precipitated minerals or whether biological processes play a role in the rock’s formation.

Clastic Sedimentary Rocks

Clastic sedimentary rocks consist of preexisting rock fragments, or clasts, that come from weathered bedrock. The majority of this sediment has been physically weathered, but some of it may also be chemically weathered. We classify this type of sedimentary rock with three main identifiers: grain size, shape, and sorting.

Grain size

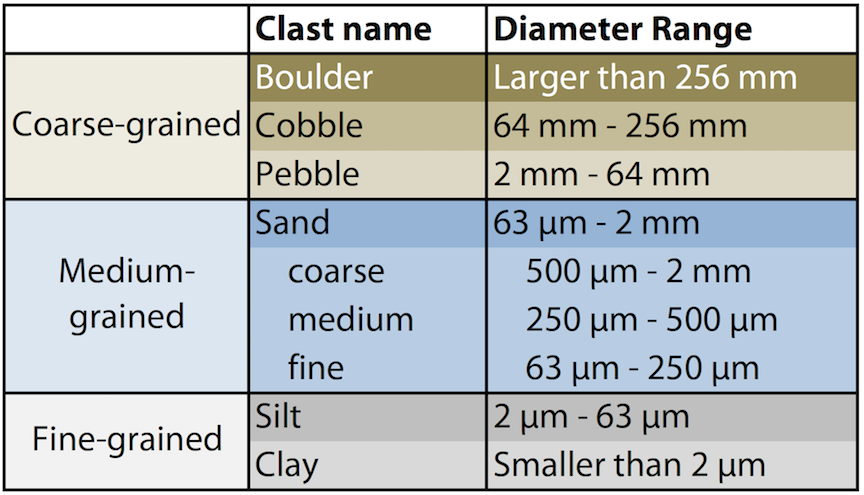

The size of the individual clasts making up a sedimentary rock is a strong indicator for the amount of energy a landscape had available for transporting the sediment. For example, extremely large fragments, such as boulders, might only be deposited by high energy processes, such as avalanches, whereas wind environments may be able to deposit smaller grains such as silt, mud and clay. Below is a diagram that gives an approximate size range for the different types of clasts that geologists encounter in clastic sedimentary rocks.

Grain shape

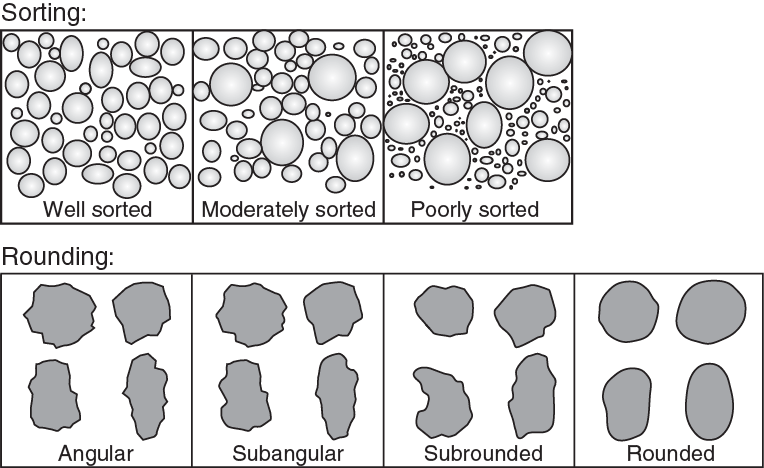

The general shape of the individual clasts within a sedimentary rock is also an excellent method to determine the type of geologic environment that may have deposited the sediment long ago. Clastic rocks with rounded grains were likely transported by water over long distances and with more energy, in which the individual sediments were abraded and physically rounded as they moved along the riverbed (Fig. 3.6.5). By contrast, angular grains indicate the sediments were transported over a relatively short distance by a landslide or mass wasting event, which did not involve water.

Grain sorting

The third identifying property of clastic rocks is the sorting of the individual clasts. A well sorted clastic rock contains clasts that have the same general size in its matrix (Fig. 3.6.5). Such an arrangement means that the clasts were transported over longer distances and/or with greater energy. A poorly sorted clastic rock contains clasts that are a mixture of different sizes in its matrix. This type of clastic rock typically tells a story of sediment being transported over very short distances.

Chemical Sedimentary Rocks

Chemical sedimentary rocks are formed by processes that do not directly involve physical weathering. When preexisting bedrock is weathered by chemical reactions that take place in water, the atmosphere, or the biosphere, that rock is broken down into its constituent elements or ions that are dissolved and transported in water.

The dissolved ions in the planet’s water supply will eventually precipitate as solid, chemical sedimentary rocks. The type of chemical sedimentary rocks that form broadly varies based on the type of elements that precipitate the rock, as well as whether organic materials contribute to the process. Chemical sedimentary rocks may contain silica, evaporite ions (sulfate and chloride), and carbonate.

We can divide chemical sedimentary rocks into two general categories: inorganic and biochemical/organic. Inorganic chemical sedimentary rocks are precipitated from only dissolved ions in the water. However, if a chemical rock requires microscopic fossils, shells, or organic material to precipitate, it is called a Biochemical or Organic sedimentary rock. As you will discover with some examples in the field guide below, a sedimentary rock can sometimes be both inorganic and organic!

Sedimentary Rock Field Guide

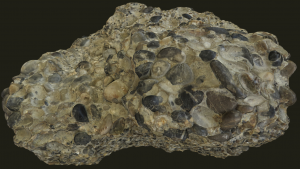

Conglomerate

“CON-GLOM-ER-AT”

Most commonly confused with: breccia

A clastic sedimentary rock. Conglomerate is poorly sorted with well-rounded clasts that are larger than sand (cobble or pebble-sized) within a cementing fine-grained matrix. In a conglomerate, the rock fragments within are sub-rounded to rounded, implying that they traveled along a high energy water source such as a steep stream or river. To tell conglomerate apart from breccia, take a careful look at the individual clasts that compose it. If most of the clasts are rounded, then your rock sample is a conglomerate.

Conglomerate often contains large rock fragments within a very fine-grained matrix, and as a result, these larger clasts are typically the first to dislodge under physical weathering.

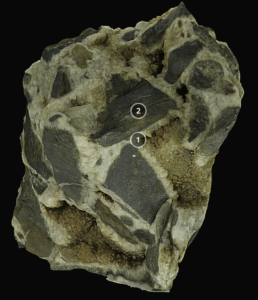

Breccia

“BRECH-AH”

Most commonly confused with: conglomerate

A clastic sedimentary rock. Breccia is a poorly sorted rock with angular clasts that are larger than sand. These clasts are cemented within a much finer-grained matrix. Breccia usually indicated that the clasts were transported over a short distance by a high energy event, such as a landslide or the movement of a glacier across the Earth’s surface. To tell breccia apart from conglomerate, look at the individual clasts within the rock. If the edges of the clasts are angular or sharp, then the rock sample is breccia.

Like conglomerate, breccia contains very large rock fragments within a fine-grained matrix, and these clasts have a tendency to dislodge first under physical weathering.

Sandstone

“SAND-STONE”

Most commonly confused with: quartzite (metamorphic)

A clastic sedimentary rock. Sandstone contains sand-sized clasts, is most easily identified by its “sandpaper” feel. Sandstone usually appears as a uniform accumulation of cemented sand, and it can vary in color as pink, gray, or beige. Sandstone is reliably deposited by desert environments as well as beaches.

Sandstone can sometimes be confused with the metamorphic rock quartzite and for good reason, sandstone is quartzite’s parent rock before it is subjected to high temperatures and pressures! (See section 3.7). Sandstone is typically rougher to the touch and contains smaller individual grains of quartz, whereas quartzite has larger, recrystallized grains of quartz throughout its matrix.

Light tan varieties of sandstone with well-sorted grains of quartz are among the most resistant sedimentary rocks to physical and chemical weathering. Sandstone is often used as bricks and other construction materials for its durable properties.

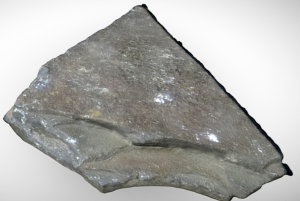

Shale

“SHAIL”

Most commonly confused with: slate, limestone, basalt

A clastic sedimentary rock. Shale is well-sorted with silt, mud, or clay-sized clasts that are tightly packed into a solid matrix. It is most easily identified by its tendency to split into thin planes, which is a property called fissility. Shale derives from very low energy environments, in which fine-grained sediment can slowly settle from still water and accumulate over time. Examples of these environments are lagoons, lakes, and continental shelves.

“Shale” is sometimes an umbrella term for fine-grained clastic rocks and the term “mudstone”, which refers to rocks made of clasts smaller than sand, also applies to shale. For the purposes of this course, “shale” and “mudstone” are interchangeable. Shale is often composed of quartz, feldspar, and clay minerals, although its color can significantly vary depending on the presence of other minerals. Shale can be pigmented red, black, green, gray, brown, etc., by different minerals.

Shale can easily be confused with metamorphic counterpart, slate, which is also fine-grained and separates into thin planes. However, with slate, the breakage is much more pronounced and foliated lines can be observed. Light and dark gray varieties of shale are similar in appearance to limestone, but shale does not contain significant quantities of calcium carbonate, and it will not react to dilute hydrochloric acid.

Shale is very susceptible to physical weathering due to the ease with which it breaks into planes. However, when buried under the Earth’s surface, shale’s fine-grained matrix can prevent liquids from seeping past, and consequently, shale has held important roles in natural gas and oil exploration.

Rock salt

Most commonly confused with: rock gypsum and calcite.

A chemical sedimentary rock. Almost every variety of rock salt precipitates inorganically from excess sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl–) ions in water. Rock salt is one of the few rocks that is composed of a single mineral, halite (NaCl), and as such, it has a predictable chemical formula and structure. As with halite, rock salt is typically white or colorless with a cubic shape or clusters of cubic crystals that have a distinctive, salty taste.

The presence of rock salt usually indicates that a wet environment has or is undergoing significant drought. Designated as an evaporite, rock salt will commonly precipitate along the edges of an evaporating lake; as water evaporates into the atmosphere, the sodium and chloride ions remaining in the dwindling water become more concentrated until rock salt forms. Rock salt may also be common to dry plains that receive periodic rainfall or regions with briny water.

Rock salt is sometimes confused with another clear, single-mineral sedimentary rock called rock gypsum. The primary difference between these two rocks can be found in the shape of the crystals. Rock salt has cubic-shaped crystals, whereas rock gypsum can have rhomb-shaped crystals. And, you cannot scratch rock salt with a fingernail.

Rock Salt has been popularly used in the food industry, city-planning (de-icing frozen streets), and agriculture. This rock can completely dissolve in freshwater, and it has a Mohs hardness of 3. Therefore, it is very susceptible to both physical and chemical weathering, and often causes sinkholes if dissolved underground.

Rock gypsum

“ROCK JIP-SOME”

Most commonly confused with: rock salt, calcite

A chemical sedimentary rock. Almost every variety of rock gypsum precipitates inorganically from excess calcium (Ca2+) and sulfate (SO42-) ions in water. Rock gypsum is an evaporite rock that is composed of a single mineral, gypsum (CaSO4 · 2H2O). Therefore, this rock has a predictable chemical formula and atomic structure. Rock gypsum is usually white or colorless with rhomb-shaped crystals or sometimes prismatic crystals. Rock gypsum is also very soft, and its surface can be scratched by a fingernail.

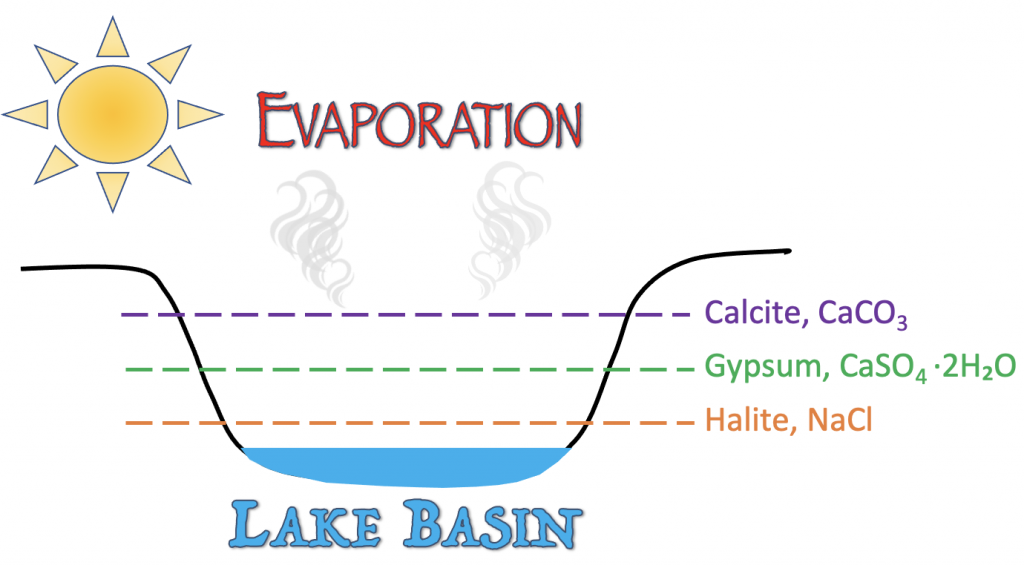

Similar to rock salt, the presence of rock gypsum in an environment or outcrop tells you that it was deposited at an arid region with either a briny or evaporating water source. These environments are often evaporating lakes or salt flats that accumulate a high concentration of calcium carbonate. It is not unusual to find both rock gypsum, rock salt, and calcite in a sequence in the same outcrop. An evaporating body of water will usually precipitate calcite first, followed by rock gypsum, and then rock salt.

Rock gypsum does not react to dilute hydrochloric acid, unlike the mineral calcite, and its crystals are usually prismatic or rhomb-shaped, unlike rock salt. Rock gypsum is softer than both calcite and halite, and therefore more susceptible to physical weathering. Rock gypsum has been traditionally used in the construction industry as a building material, such as drywall.

Chert

“CHURT”

Most commonly confused with: obsidian, quartz

A chemical sedimentary rock. Chert can be both inorganically and biochemically precipitated in groundwater or the ocean, and it is usually composed of silica. Inorganic varieties of chert form exclusively from dissolved silica in high-temperature, high-pressure groundwater. When this geothermal water source rises to the surface, it can no longer keep the silica in a dissolved state, and it precipitates as solid chert.

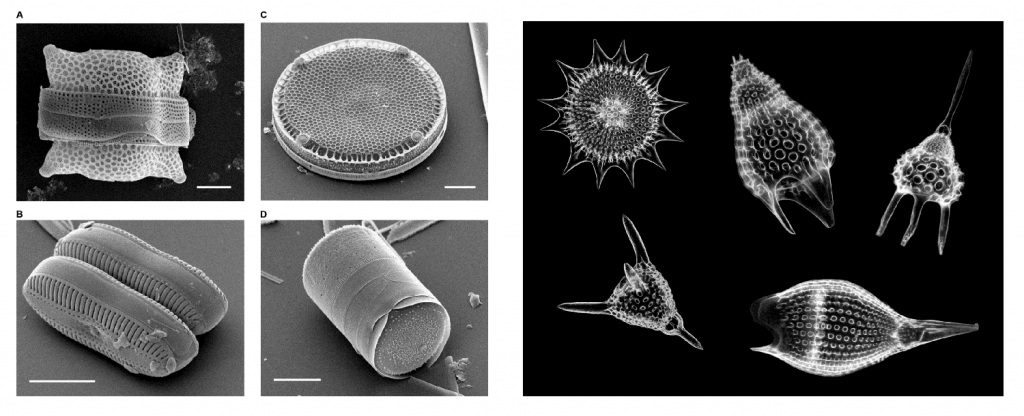

Biochemical varieties are formed when silica-based skeletons such as radiolarians and diatoms accumulate on the seafloor after they die. That sediment cements together to form biogenic chert.

We call chert “jasper”, “flint”, “onyx”, and “agate”, which reflect the wide variety of hues and colors that this rock can have. However, chert is most easily identified by the curved conchoidal fracture pattern it displays, which is also present in obsidian and quartz. But, chert is not as glassy or reflective as these rocks and minerals.

Because of its high silica content, chert is very durable and resistant to weathering. This property has made chert desirable in the construction trade as a road material and gravel. Like onyx, it has been traditionally used as a weapon in spearheads and arrowhead for thousands of years.

Limestone

Most commonly confused with: shale, basalt

A chemical sedimentary rock. Limestone can be both inorganically and biochemically precipitated in seawater, and it primarily composed of calcium carbonate. Inorganic limestone forms in the deep ocean when seawater reaches colder depths that cause the dissolved ions calcium (Ca2+) and carbonate (CO32-) to precipitate as solid rock. There are several varieties of limestone that incorporate both the ions and organic material from marine organisms when forming a solid matrix. These types of limestone, described in more detail below, are biochemical sedimentary rocks.

Limestone is often light to dark gray, or tan, and it can be scratched by a penny. Limestone is composed of calcium carbonate (calcite, (CaCO3) and dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2). This rock will strongly fizz when exposed to dilute hydrochloric acid (remember the properties of calcite in video 3.2.3). This reaction clearly distinguishes limestone from other dark gray rocks such as shale and basalt.

Limestone is very susceptible to chemical weathering by dissolution as rainwater and groundwater are both slightly acidic. Consequently, regions with underlying limestone often have caves and experience sinkholes. Despite its tendency to weather over long periods of time, limestone has been (and remains) a popular construction material for thousands of years, dating back to the Great Pyramid of Giza in Ancient Egypt.

Fossiliferous Limestone

“FOSSIL-LIFF-ER-RUS LIME-STONE”

Most commonly confused with: limestone

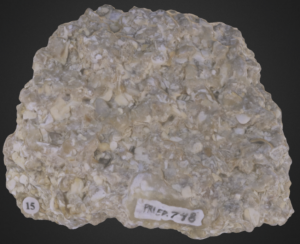

A biochemical sedimentary rock. Fossiliferous limestone specifies a type of limestone that includes visible fossils within the rock’s matrix, and therefore, it is biochemically precipitated. Fossiliferous limestone may contain the remains of shells, brachiopods, trilobites, plants or many other types of other animals.

Fossiliferous limestone can form in the deep ocean or near coral reefs, which are composed primarily of calcium carbonate. The surrounding matrix has the same properties as limestone (see above), and this rock will react when exposed to dilute hydrochloric acid. However, macrofossils within the rock distinguish fossiliferous limestone from inorganically precipitated limestone.

Coquina

“CO-KEEN-AH”

Most commonly confused with: n/a

A biochemical sedimentary rock. Coquina is a biochemical variety of limestone that is composed of shells, fossils, and sand that have been poorly cemented together. Coquina is often tan in color with shells that are easily visible to the naked eye. Most of the material within coquina is composed of calcium carbonate, and it fizzes in contact with dilute hydrochloric acid.

Coquina can often be found along beaches or tidal pools in which there are abundant shelly creatures. The leftover shells, sand, and fossils are eventually clustered together by wave action and cemented together upon burial. Coquina is usually not well-cemented together, and it is easily weathered and reworked by physical and chemical weathering processes.

Chalk

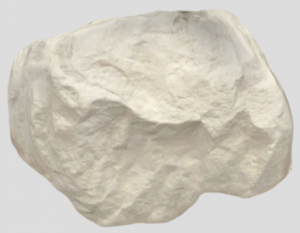

Most commonly confused with: n/a

A chemical sedimentary rock, sometimes also called marlstone or marl. Chalk is a biochemical variety of limestone that is composed of microscopic shells from an oceanic organism called a coccolithophore or coccolith. When these organisms die, their calcium carbonate-based shells accumulate along the bottom of the ocean as an ooze-like sediment, which eventually cements as chalk.

Chalk is distinctively white, powdery, and extremely soft to the point of crumbling when touched. It is easily weathered on the Earth’s surface and typically is collected by mining. Chalk has traditionally been used on school boards, but its use has since been widely discontinued in favor of gypsum.

Coal

Most commonly confused with: obsidian

An organic sedimentary rock. Coal is one of the few organic sedimentary rocks that is composed of dead plant matter. When enormous amounts of plant matter decay and accumulate from an environment, such as swamplands or dense forests, it eventually becomes buried within the Earth’s surface. There, over millions of years and at high temperatures and pressures, this matter will transform into solid, black rock.

Coal is easily identified by its low density, dark black color, and soft, crumbling surface. Because it has been formed by organic matter, it is mostly made of carbon (C). Although obsidian is also black and shines like coal sometimes does, obsidian is much harder and more resistant to breaking.

Coal is combustible, and it has reshaped how societies are powered by electricity. Byproducts of burning this rock are commonly called fossil fuels, and they have contributed to significant climate problems that the world is currently facing.

rocks that cement together from weathering products, either from sediments or chemical ions in water.

The process in which fluids, such as water, move into the pore spaces between loose sediments and - through chemical reactions - act as a bonding agent between the grains.

The process in which gravity and the pressure from overlying layers of rock cause loose sediments to press together.

The solidification of loose sediment materials as solid sedimentary rock through compacting pressures and cementation.

Rocks that crystallize from molten materials beneath the Earth surface or from volcanic processes.

Rocks that form when any type of preexisting rock is warped or transformed under elevated temperatures and pressures.

A type of weathering that involves the abrasion and breakdown of existing rocks and minerals by water, the atmosphere, and biosphere. Also known as mechanical weathering.

The dissolution, disintegration, and alteration of preexisting rock by reactions that take place at the molecular scale.

A category of sedimentary rocks that are made from the solid fragments of preexisting rocks.

A category of sedimentary rock that has formed the precipitation of solids from water. The elements that make up this rock have been, at one time, chemical weathered from preexisting rocks.

A charged atom or molecule.

a solid, inorganic, and crystalline substance that has a predictable chemical composition and form by natural processes.

A fragment that makes up a Clastic Sedimentary rock that was once originally part of an older rock type.

A process of physical weathering in which a rock is worn down through contact with energetic environments over time.

The process in which rock, soil, or sediment moves down a slope under the force of gravity. Mass wasting is an umbrella term that includes hazards such as landslides, debris flows, rock falls, and mudslides.

A pure substance that is not composed of any other ingredients found in the Periodic Table of Elements. One atom can be composed of only one element and form bonds with other elements.

a compound composed of silicon and oxygen in the formula SiO2.

"salt" minerals that form through the evaporation of a standing body of water.

CO3--

The anion group consisting of one carbon bonded to three oxygen atoms. Carbonate is a key ingredient in calcite, limestone, and is a solid form of carbon dioxide (CO2).

A subcategory of sedimentary rocks that are precipitated from dissolved ions in water. None of these rocks form with preexisting organic materials and/or fossils.

A subcategory of sedimentary rocks. This type of rock will typically form from the shells of marine organisms.

A subcategory of sedimentary rock that specifically forms from the remains of animals and plant matter.

A type of clastic sedimentary rock that consists of angular pebble or cobble-sized clasts that are cemented together with finer-grained sediments.

A type of clastic sedimentary rock that consists rounded pebble or cobble-sized clasts that are cemented together with finer grained sediment.

A non-foliated (granoblastic) metamorphic rock that was once a quartz-rich sandstone.

A type of clastic sedimentary rock that is composed of sand-sized clasts.

A very common rock-forming silicate mineral with formula SiO2.

A foliated and fine-grained, low-grade metamorphic rock that is originally made from shale.

An organic or chemical sedimentary rock that is primarily composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Limestone is a subgroup of rocks that includes chalk, coquina, and fossiliferous limestone.

an igneous rock that is mafic and fine-grained. Basalt is dark and makes up the majority of the oceanic crust.

A clastic sedimentary rock made of very fine-grained sediments such as muds, clays, and silts.

The tendency, usually of sedimentary rocks and layers, to split along planes of weakness.

A group of silicate minerals which represents the most abundant mineral class of the continental crust.

A group of silicate minerals that typically forms after existing rocks and minerals, such as feldspars, are chemically altered by water.

The arrangement of thin layers or repetitive structures in metamorphic rocks that results from the uneven applications of heat and pressure within the Earth's surface.

An inorganic, chemical sedimentary rock composed only of the mineral gypsum (CaSO4 * 2H2O).

An inorganic, chemical sedimentary rock composed only of the mineral halite (NaCl).

NaCl

A salty, halide mineral that is often colorless or white. Halite is commonly known as rock salt and used globally as a condiment. It tends to form as cubic-shaped grains or crystals.

The numerical scale, from 0-10, that measures the hardness of a mineral. "0" is a very soft, crumbly mineral and "10" is diamond-hard.

CaCO3

A carbonate mineral that strongly reacts with dilute acid. Calcite composes the sedimentary rock limestone and composes the skeletons of some ocean life.

A common evaporite mineral that precipitates in dry or arid environments near evaporating water. It has the formula CaSO4 * 2H2O.

A felsic, extremely smooth, fine-grained igneous rock that is glassy in texture. Obsidian is primarily composed of amorphous silica and displays conchoidal fracture.

A sea-dwelling microorganism with a silica (SiO2)-based mineral skeleton.

A type of sea-dwelling microalgae with a mineralized, silica (SiO2)-based skeleton.

The breakage of a rock or mineral that forms smooth, curved surfaces.

A carbonate mineral, CaMg(CO3)2, that is more resistant to weathering by acid at room temperatures. Dolomite often composes the material of fossilized shells.

A variety of chemical weathering by which rock is stripped away at the molecular structure by water or solutions containing acid.

A biochemical sedimentary rock that is a type of limestone, which includes visible fossils within the rock's matrix.

A shelled water-dwelling organism from the lophotrochozoan group of animals. Although they appear like clams, there is asymmetry between the top and bottom shells.

An ancient, sea-dwelling creature from the arthropod family with a body separated into three lobes. Trilobites went extinct about 252 million years ago during the Permian Mass Extinction.

A biochemical sedimentary rock and variety of limestone that is composed of shells, fossils and sand that are poorly cemented together.

A round, oceanic microorganism with a calcium carbonate exoskeleton consisting of multiple plates. Sometimes also called a coccolith.

An organic sedimentary rock formed by the compaction of plant and animal organic matter over millions of years.

The measure of how tightly packed atoms are in an object or material in a given volume. It is determined by figuring out its mass, divided by its volume.

A type of fuel source that has formed on the planet from natural processes.