6.5 Flood Mitigation

Merry Wilson

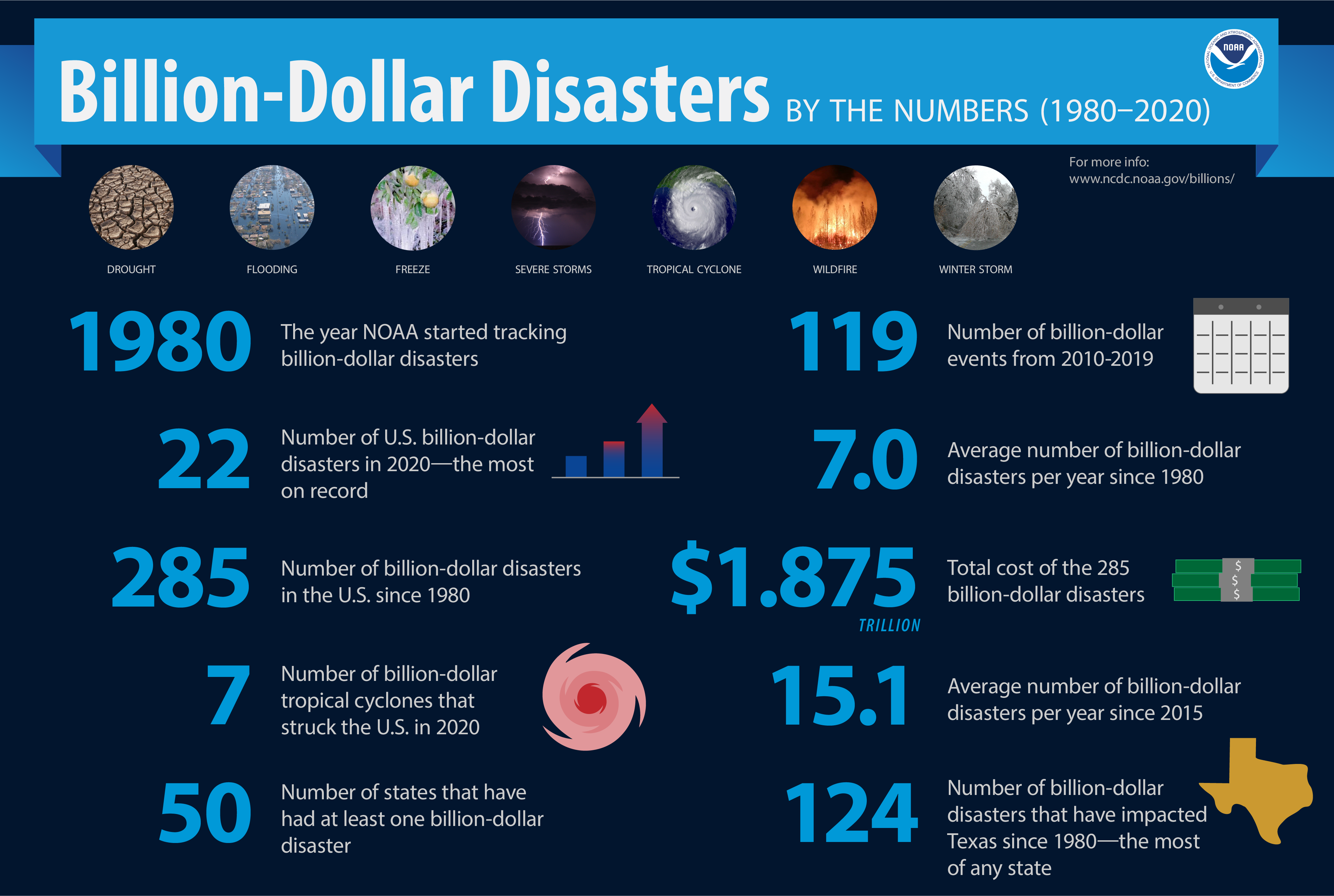

Flooding occurs in every U.S. state and territory, and kills more people each year than tornadoes, hurricanes, or lightning and costs on average $5 billion per year to (NOAA, 2021). Flooding is inevitable when living near a stream, and there are many hazards associated with flooding. Hazard mitigation is any sustainable action that reduces or eliminates long-term risk to people and property from future disasters. Mitigation planning breaks the cycle of disaster damage, reconstruction and repeated damage. Hazard mitigation includes long-term solutions that reduce the impact of disasters in the future (FEMA, 2021).

Flood Control Structures

We construct flood control structures to protect residential areas, businesses, and agricultural lands from the potential devastation of large flood events. Sometimes these structures allow water to flow more slowly through the watershed, allowing flood waters to recede to a less dangerous stage. Other times the block water entirely from entering an area. When they work well, flood control structures can allow people and rivers to interact in a predicable patter, but when they fail, they can often be devastating events.

Video 6.5.1. How do large-scale flood control structures work in rivers? (11:17).

Dams

A dam is a structure that is built to stop river water flow. These are built as flood control features and are also used to store water in reservoirs for irrigation, public consumption, and to produce hydroelectric electricity. People try to protect areas that might flood with dams, and dams are remarkably effective. Dams are also used to control regional flooding events by slowing the release of water, so that it does not overwhelm a single trunk stream all at one time. When a dam breaks along a reservoir, flooding can be catastrophic. High water levels have also caused small dams to break, wreaking havoc downstream (1).

Historic Flooding: Dam Failure

While dam failure is infrequent, the results can be devastating.

- Johnstown, PA, 1889. The deadliest flood in U.S. history. Several days of extremely heavy rain overwhelmed a small drainage basin and caused dam collapse, killing 2,200 people.

- Rapid City, South Dakota, 1972. A flash flood filled a dam with debris and caused it to fail. 238 people died.

Levees

People may also line a riverbank with levees, high walls that keep the stream within its banks during floods. Sometimes these are earthen structures, made of mud and sand, and sometimes they are made of concrete. A levee in one location may force the high water up or downstream and cause flooding there. The photo below is of a broken levee after a flood in Kansas City, along the Missouri River, in 2011. That year, record rain and snowmelt overwhelmed more than 850 miles of open river between North Dakota and the Mississippi River in St. Louis. Dams along the Missouri tried to regulate the water in the river, but calculations did not allow enough water release and large-scale flooding ensued. Sometimes levees are breached intentionally in order to flood less populated areas and save more urban areas from extensive damages.

Figure 6.5.2. Kansas Flood, 2011, US Army Corps of Engineers, Public Domain.

Historic Flooding: Levee Failure

While we build levees to keep floodwaters away from businesses and homes, when they fail, they can cause more massive flooding that would have occurred without them.

- Hurricane Katrina, 2005. The Hurricane itself was only a Category 3 storm when it reached land, but it destroyed New Orleans aging levees, which were holding back large amounts of water. The result was more than 80% of New Orleans was under water, 1800 people died, and this was the costliest natural disaster in US History at the time.

- The “Great Mississippi Flood”, 1927. The Mississippi River saw record rain and snowmelt, and the river breached the levees, flooding over 27,000 square miles, killing 250 people, and displacing more than 700,000.

Retention Basins and Canals

Retention basis are small depressions that are constructed to capture storm water that may cause flooding and allow water to be released more slowly. You’ve probably seen them surrounding shopping malls, or even at a school. When not flooded, sometimes these features are used for recreation and as urban green spaces. The canals seen throughout the Phoenix area are also used as flood control features. While they are also used to transport water throughout the city for irrigation, they collect and manage floodwaters when monsoons do regularly flood the city.

Backyard Geology: Hohokam Canal System

Modifying river systems is not a new idea. The Hohokam, a prehistoric group of Native Americans that lived in the area that is now Phoenix, built an extensive canal system. Over 700 miles worth of canals, built between the years of 600-1400 AD, serviced over 100,000 acres of desert land. This canal system is considered the largest in the New World, and the oldest in what is now the United States. These were entirely constructed by hand without the benefit of modern survey instruments, machinery, or wheeled vehicles. Their major canals averaged about 8 to 12 miles and were largest at the headwaters and tapered throughout their length so that the velocity was maintained between approximately 1.5 and 3 f/s (ft per second) throughout the system. They also adjusted their construction based on the terrain. The Hohokam developed four different types of distribution systems depending on the terrain. In addition, their system was a dynamic irrigation system. When conditions changed, such as a canal filling with silt, they would abandon the canal and build a new one adjacent to the old one. Around 1450 AD, the Hohokam abandoned the area for unknown reasons, but the leading idea was that they could not keep up with the water needs in the hostile terrain. Hohokam is derived from the Akimel O’odham word for “those who have gone” or “all used up.”

Figure 6.5.4. A restored Hohokam canal that is currently used for present-day irrigation throughout the Phoenix Area. Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA.

Urbanization and Flooding

The increase in urban society brings many land use changes with it. Vegetation is removed or changed, impermeable surfaces like homes and buildings are constructed, and many changes are made to natural waterways. All of these changes influence the amount of surface runoff in a given area. With less natural water storage capacity and more rapid runoff, urban streams have higher, faster peak discharge rates than more rural streams.

Changing river dynamics can also alter the stream stage, and cause typical rainstorms to become flooding events. Construction of bridges is a common occurrence in urbanization that can significantly alter stream stage by constricting water flow.

Flood Events

As discussed, flooding occurs when a drainage basin is overwhelmed by water and streams overflow. Sometimes this can occur very quickly in a flash flood, and sometimes it grows over days, weeks, and months. All flooding can cause power outages, disrupt travel, damage buildings, create landslide events, and are considered a threat to life. There are some ways to stay safe during floods.

Prepare

Though disasters cannot be stopped, they potential damages can be somewhat mitigated through preparation. According to FEMA, there are important considerations to prepare for flooding.

- Know whether you are located on a floodplain or designated flood zone.

- Build a “Go Kit” composed of supplies you may need if you need to move from your location, as well as maintaining supplies if you need to stay several days without power or water.

- Find out if your community has a flood warning system, and sign up.

- Know the signs that could lead to flash flooding.

During

The general “rule of thumb” regarding floods is to NEVER enter floodwaters. FEMA advises, “Turn Around, Don’t Drown!”, with an emphasis not to every walk, swim, or drive through flood waters. The State of Arizona has a law, nicknamed the Stupid Motorist Law, that requires that any motorist that becomes stranded by entering a flooded area can be charged for the cost of their own rescue.

Common sense measures can be followed during flood events.

- Never enter a flooded area.

- If told to evacuate, do so immediately.

- Stay off bridges, because they could be prone to wash away in fast moving water.

- Go to the top floor or roof of a building

After

The size and impact of flooding events vary widely, depending on many factors. In general, it is best to listen to local authorities in order to determine the best course of action after a flood.

- Never enter a flooded area, as there could be risk from electrocution, debris, and fast moving water.

- Beware that structures could have been compromised and may be unsafe.

- Animals, particularly snakes, may have taken refuge in your home.

Costs of Flood

According to the National Centers for Environmental Information, flooding is one of the most universal and costly weather and climate related hazards in the United States. Riverine flooding events cost, on average, $4.6 billion dollars per event. This is independent of flooding events related to tropical cyclones and severe storms, and accounts for over 8% of the total costs of all weather and climate disasters in the United States in the last 40 years (NOAA, 2021).

not allowing fluids to pass through

precipitation that flows out over the landscape

the volume of water moving down a stream at a given time, often measure in cfs (cubic feet per second)

water level in a stream

land area drained by a stream and its tributaries

a sudden local flood, typically due to heavy rain.

a flat-lying area of land next to a stream that experiences flooding during periods of high discharge